Translate this page into:

The origin and evolution of the first modern hospital in India

Corresponding Author:

J.M.V. Amarjothi

Madras Medical College, Rajiv Gandhi Government General Hospital, Chennai, Tamil Nadu

India

drmosesvikramamarjothi@hotmail.com

| How to cite this article: Amarjothi J, Jesudasan J, Ramasamy V, Jose L. The origin and evolution of the first modern hospital in India. Natl Med J India 2020;33:175-179 |

Introduction

India is an ancient country where traditional systems of medicine such as Ayurveda, Siddha and Unani have been practised for thousands of years. However, the first organized hospitals were established by the colonial powers who made a beeline for India after the Portuguese explorer Vasco de Gama discovered the sea route to India in 1498.[1] The Portuguese established Goa, a centre on India’s western coast as their ‘capital in the Orient’ in 1510.[2] Although Portuguese physicians were present in India even before the British formed a trading company, it was the British who established the first hospitals.[3]

The East India Company (EIC) was by far the dominant colonial power in India and established Madras (present day Chennai) as their seat of power east of the Suez. (The Suez canal was opened for commercial shipping only in 1869, about 200 years later.) Later, the seat of power shifted to Calcutta (present day Kolkata), further to the east, as the EIC started making inroads into the hinterland.

In 1639, EIC officials, Andrew Cogan and Francis Day were instrumental in establishing Fort St George, christened after the patron saint of England, near a small town, Madrasapatnam on the eastern (Coromandel) coast of India.[4] In this fort, the first modern hospital in India was started.

The First Hospital (1664–1678): Cogan’S House, Fortst George

Since the year of its foundation in 1600, the EIC always made provisions for surgeons to cater to the medical needs of its employees, with even the first trading ships carrying surgeons. John Woodall, a leading London Surgeon at St Bartholomew’s Hospital, was employed by the Company as their ‘General Chirurgeou’. He was instrumental in the selection of medical officers for ships. In 1617, he published The Surgeon’s Mate a manual describing not only the contents of the surgeons’ chest, but also regulations to select officers for ships.[5]

The first hospital in the fort was started in late 1664. In a letter dated Wednesday, 16 November 1664, the Fort council members, William Gifford and Jeremy Sambrook wrote to Governor Edward Winters, that English soldiers posted to the fort had died due to sickness.[6] Surviving soldiers had complained that their wages were not enough to support them in their sickness. Hence, they had rented the former lodgings of one of the founders of the fort, Andrew Cogan, for 2 pagodas a month. (The pagoda was a priced gold coin minted by the EIC in India.) These rented rooms were, however, uncomfortable, crowded by any standards and could treat 8–10 men only.[6]

The reason for renting of the hospital premises was because space was at a premium in the fort. The congestion was so bad that even Governor Edward Winters was forced to use rooms in his private mansion to store the company’s merchandise.[6] In 1665, Philip Bradford was appointed the first ‘Chirugion to the fort’.[6]

The Second Hospital (1679–1688): ‘The Collegium’

The second hospital was much more spacious, near the St Mary’s Church which is at the centre of the fort[6] [Figure - 1] and [Figure - 2]. In the next 15 years, this hospital would undergo a series of renovations and extensions. So, by 1688, it was transformed into a spacious two-storeyed building managed by the church, with generous contributions from the European public playing a major part in its expansion. However, it was still open only to service personnel of the EIC and not the European or native public.

|

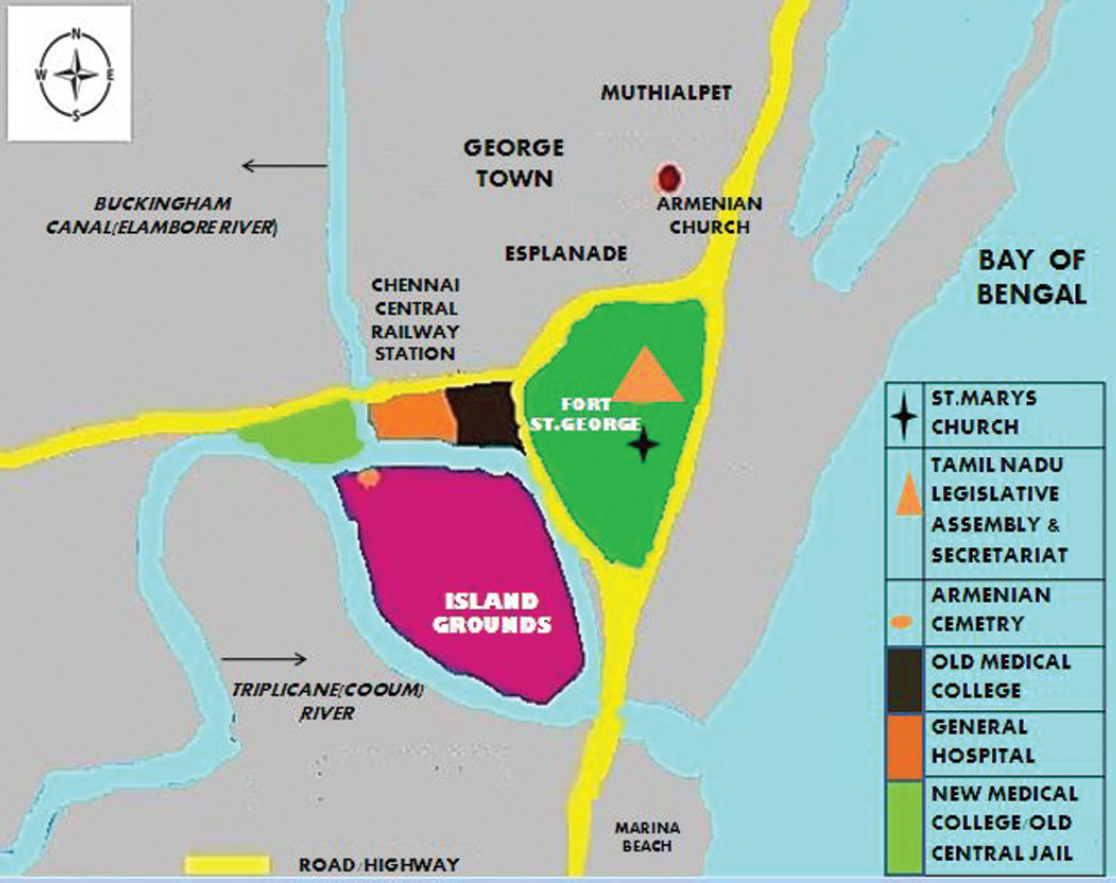

| Figure 1: Map of Government General hospital, Fort St George and surroundings (2018). Map not to scale. The area under Fort St George (green) includes the fort per se, with barracks, armoury and parade grounds |

|

| Figure 2: Fort St George: Erstwhile home of the hospital. Today, it houses the secretariat and legislative assembly of the state of Tamil Nadu (seen in the foreground with the flagstaff on the right). The spire of the St Mary’s church can be seen on the left (blue arrow) |

In 1688, there was a mass influx of Company men and merchandise from further north due to local conflict. This forced the fort authorities to take over the now spacious, two-storeyed hospital premises located at the heart of the fort. They paid the church 838 pagodas and after shifting the hospital to a temporary premises and used the upper storey for lodgings and the lower quarters for storing precious merchandise.[6]

The history of this old hospital building is interesting. Afterwards, its use had changed into a place of instruction and staff quarters for young writers of the Company and a warehouse. It is interesting to note that, much later, Sir Henry Yule (1820–1889), a noted Scottish linguist, writer, traveller and engineer in the EIC, referred to this edifice as a ‘madrassa’ in his book and erroneously suggested that this gave the city of Madras its name.[7]

The Third Hospital (1688–1690): St James Street

The hospital was moved to a temporary place, the erstwhile residence of a John Pois at St James street in the fort.[8] The exact location of this street which contained a lot of warehouses of the Company is a matter of dispute with two maps (map of 1688, and the other of Thomas Pitt, in 1710) referring to two different streets by the same name.[6]

The Fourth Hospital (1690–1712): The Hospital of Elihu Yale

The fourth hospital which was located at the northern end of the fort, near the Elambore river (Buckingham canal; [Figure - 1]), was designed in Tuscan style like the barracks and built at a sum of 2500 pagodas, with the church investing the entire amount got from sale of the second hospital and the then Governor Elihu Yale (1687–92; of Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut fame) contributing 1700 pagodas from the Company treasury.[6] It is interesting to note that this largesse from the governor would be in the eye of a storm later with one of his successors, Thomas Pitt, appointing a fact-finding mission to look for any financial culpability on Yale’s part during his brief detention after his governorship.[6] Yale was allowed to leave India in February 1699. He died in England, never visiting India again.[9]

The hospital was very spacious from accounts of travellers such as Charles Lockyar and Thomas Salmon.[10] The hospital was connected to the fort barracks and had its own spacious veranda, plaster room and apothecary room.[6] The soldiers and sailors of the Company treated there were on different schemes. The soldiers did not pay for medications as their entire pay went to the steward during the period of their convalescence, whereas the sailors paid a shilling a day out of their pockets.[6]

Although this hospital was solely used for the Company’s soldiers (like the first hospital), it was soon opened to the European public acknowledging their contribution. This joint partnership between the public and the Company continued for another 200 years till 1899 when the hospital became a truly civilian hospital.

The hospital was manned by eminent ‘surgeons of the fort’ like Samuel Browne and Edward Bulkley.[6] These doctors were experienced and could prescribe ‘physick’, (physick-archaic term for prescribing medication, more specifically laxative) and ‘do manual operations’.[11] The hospital team included a surgeon general with an annual salary of 36 pounds with allowances for horses and rations of oil and wax. He was assisted by a surgeon’s mate on a pay of 5 pagodas a month and an assistant on 3 pagodas a month. A stewart was also appointed to take care of those in sickness and penury in the fort.[6]

The hospital was connected with the one of the first cases for criminal negligence on the part of a physician in India when on 30 August 1693, the apothecary under surgeon Samuel Browne gave a Mr John Wheeler ‘a physick’ ground on the same mortar on which he had previously ground arsenic. However, the death could not be proven due to negligence even though an autopsy was done by Edward Bulkley. It is to be noted that this is the first record of a medico-legal autopsy in India.[8] However, no chemical tests were done, and Samuel Browne was later acquitted by the court jury for lack of evidence.[6]

The surgeons in the fort, in addition, gave status reports on the physical and mental conditions of people examined to the fort’s governing council. For example, they gave a report on Mr John Niles that he was ‘in melancholy, want of exercise and his breathing of stagnant air’. This report was accepted, and Niles was moved to better surroundings.[6]

From January 1698, surgeon Edward Bulkley was on his own as Samuel Browne was transferred out as the fort authorities realized that they employed one surgeon too many. Like any good surgeon, in a letter to the Company officials, Bulkley makes a request for more personnel, better equipment and comfortable living quarters. The exact list written to the directors pled for a surgeon’s mate, an assistant, four coolies (men for manual labour), European medication for 50 pounds, locally procurable medication, mortars, utensils, vessels, cots, bedding, apparel, diet for patients and of course, better quarters for the surgeons.[6]

The Fifth Hospital (1712–1746): The Extended Hospital

The hospital at the northern end was further extended on the estate of Henry Greenhill (a council member and accountant) and the church house during the tenure of Governor Edward Harrison (1709–1717). It was intended to accommodate 100–150 inpatients and built at a cost of 7000 pagodas with the Company footing 1500 pagodas and the rest from the public.[10] The administration of the hospital was jointly by the Company and the church. It is interesting to observe the increasing cost of new construction owing to the larger accommodations being built and the increasing proportion of public funding in these hospitals.

Further congestion in the fort was unavoidable due to the increasing influx of soldiers prompted by repeated skirmishes of the British who were now battling for supremacy of the Coromandel coast with the French. The hospital again became a casualty in this rivalry. Matters came to a head when the French occupied Madras in the second Carnatic war (1746–1749). The hospital was abandoned, and the staff were transferred to Fort St David further along the coast to the South. The hospital returned to Madras when the city was returned to the British after the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle (1748) in exchange for Louisbourg in the Americas to the French.[12] To ward off further threat of invasion, the previous hospital premises in the fort was converted into barracks and the hospital was transferred to Pedanaikpettah, outside the fort in 1753.[10]

The Sixth Hospital (1753–1757): The ‘General Hospital’

This hospital was built outside the fort on land acquired from Portuguese residents living there on what is now the North West Esplanade [Figure - 1]. However, the hospital ran into a lot of problems and patients in the hospital were not comfortable being repeatedly exposed to the notoriously inclement weather and further improvements were needed desperately.[10]

The Seventh Hospital (1757–1758)

The hospital was moved further to a location (Muthialpettah) which is closer to the present site [Figure - 1]. To improve the working of the hospital, surgeons Robert Turning and James Wilson, in a letter to the directors in 1757, urged further expansion to 200–250 inpatients, with ‘salivating rooms for 30 men, holding capacity for 200–300 sailors’.[10] They also asked for better operation tables, chests of bandages and other equipment.[10] However, storms both weather wise and political (in the form of a siege by the French EIC under, a brilliant general Comte de Lally) struck this hospital, necessitating another shift in location.[13]

The Eighth Hospital (1758–1759): The Field Hospital

The eighth hospital was back in the precincts of the fort and was more of a field hospital during the raging siege (third battle of the Carnatic) fought between the British and the invading French.[14] The house of a Solomon Franco in the fort was chosen as the field hospital during the entire length of the unsuccessful siege by the French EIC.[11]

The Ninth Hospital (1759–1772): ‘The Armenian Quarters’

After the war with the French, the hospital was moved to the area previously occupied by the Armenian churches and cemetery at a rent of 15 pagodas a month. George Pigot, the then governor, worried of the financial implications and unsanitary conditions of this location, wanted a better place to build the hospital. Hence, a search was made for a suitable location to build the hospital.[11]

The Tenth Hospital (October 1772–): ‘Hogg Hill’

The hospital was shifted to its final place which was previously used as a garden by Company officials. It was called Hogg Hill or NariMedu (Tamil, for wolf mound). It was an ideal place––airy, elevated and uncongested. It was just outside the walls of the fort located at a bend in the Triplicane (Cooum) river flowing near the fort [Figure - 1].

The elevation of the Hogg Hill near the fort had always been a point of great concern for the fort authorities, especially in case of a siege. Hence, a reduction in the incline of this elevation was planned, and the site was to be prepared for a hospital with 600 inpatients. It was thought that the cost of altering the topography of the entire area and construction would be as high as 85 000 pagodas. The governing council decided to tender the construction to the lowest bidder who turned out to be John Sullivan, a young writer in the Company with a winning bid at only 42 000 pagodas.[10] The final hospital built was a single-storeyed structure in two blocks.

A medallion was present on the wall of this hospital which said ‘founded in 1753’. This is not historically accurate as it had a continuous history dating back to 1664,[11] and the present hospital was the tenth in the long line. The hospital initially had much autonomy with a contract system where the surgeons were free to supply nursing and other articles for a fixed price per person per day. They could also supply medicines (native and European) themselves and were entitled to even permission to go on leave to procure them.[11],[15]

Later, much centralizing reforms were introduced with the cancelling of the contract system, formation of a hospital board of senior surgeons and an effective referral system to the hospital from the Company’s regiment hospitals around Madras. The directors of the Company would further restructure the administration and set up in 1786, a hospital department, for the Company’s soldiers with a physician general, chief surgeon and head surgeon.[14]

Evolution of The Hospital at The Present Site

Further evolution of the hospital is well known with the setting of a medical school on the government order of Governor Fredrick Adam (1832–37) dated 13 February 1835 with expansion in phases in 1842, 1859, 1893, 1928, 2005 and 2010.[15] The medical school was opened to natives in 1842 and was made a medical college in 1850.

Renovations of 1842

The hospital in 1842 was in the shape of the letter H with two parallel rows of buildings (the east and west wings) connected in the middle. One half of it was reserved for the company soldiers and another for Europeans, presumably civilian men, European women and children. Natives were in the surrounding tiled enclosures which were separate.[15]

Renovations of 1859

By 1859, the role of the EIC in the affairs of India was at an end, and India was taken over by the British crown. Mirroring this, the role of the Company in the affairs of the hospital was now supplanted by the British army. In 1859, the entire hospital doubled in size and become a two-storeyed building with the west wing used for civilians and the east wing (station hospital) for soldiers.[15] The civilians too were segregated with the upper storey used by Europeans and Anglo-Indians and the lower storey for the natives.[15] The women and children, part of the hospital, were transferred out in 1861 to Vepery and 20 years later to the old lying-in hospital at Egmore. Outpatients were treated from 1862 and in 1884, a separate outpatient department was built with another being built in 1934 under Governor Stanley (1929–1934). Incidentally, this building has been pulled down in recent renovations, and the outpatient department has been moved to the erstwhile medical college premises.

Renovations of 1893–1897

In 1893, another storey was added to the already two-storeyed civilian (western wing) hospital. The station hospital was moved out in phases from the western part in 1895 and the eastern part in 1899, making it a fully functional civilian hospital in 1899.[15]

Renovations of 1928

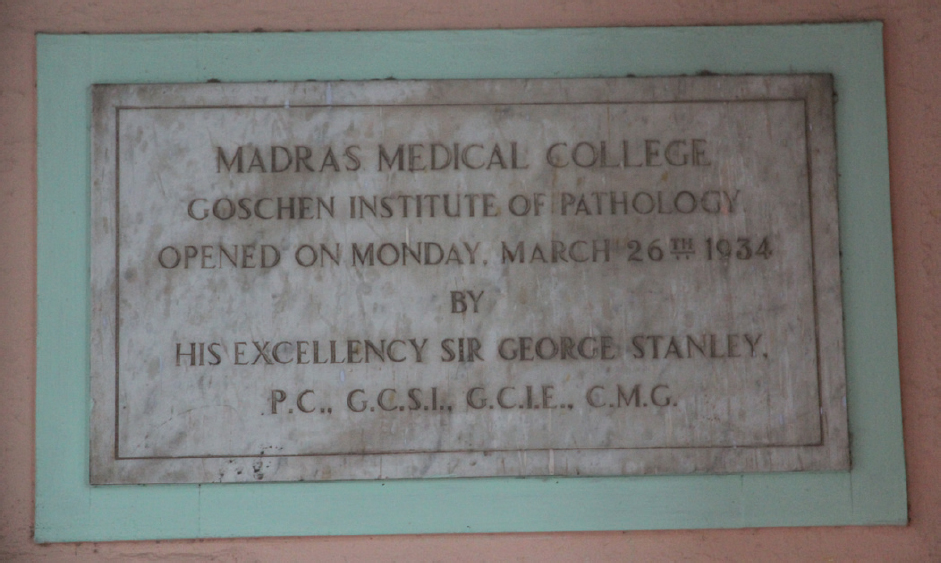

Further remodelling and renovations were done in 1928 during the tenure of Governor Goschen (1924–1929) where a state-of-the-art radiology department for that time was added to the hospital in addition to new buildings in the medical school (the Goschen block). The pathology department is still called Goschen Institute of Pathology as it was located in the Goschen block [Figure - 3] and [Figure - 4]. In the recent spate of renovations since 2015, the pathology department has been shifted to the premises of the old central jail which was acquired in 2010 as a part of the new medical college.

|

| Figure 3: Old Goschen block of pathology––now outpatient department |

|

| Figure 4: Plaque on the wall at the block |

Renovations of 2005

The old hospital building was demolished in 2002, and two new tower blocks were constructed in 2005. These six-storeyed buildings have 16 operation theatres in addition to wards, augmenting the existing bed strength by 600 to more than 3500 [Figure - 5] and [Figure - 6].

|

| Figure 5: The six-storeyed tower block of Rajiv Gandhi Government General Hospital today |

|

| Figure 6: The twin tower blocks on the occasion of the 175th anniversary of the founding of the medical college in 2010 |

Renovations of 2010

With the acquisition of the old jail premises to the west of the hospital along the Cooum river, the hospital was further extended into the premises of the old medical college and the college was moved to the erstwhile jail premises in 2012 [Figure - 1] and [Figure - 7]. All that remains of the previous central jail complex is the high-security outer perimeter fence in the new medical college premises [Figure - 8].

|

| Figure 7: The newly built college on the premises of the erstwhile central jail |

|

| Figure 8: Vestiges of the high-security outer perimeter fence of the central jail in the new medical college premises |

The hospital is now known as the Rajiv Gandhi Government General Hospital after the former Indian prime minister (1984–1989). It is fully state owned and is the flagship hospital of the state of Tamil Nadu.

We see a gradual evolution in both the ownership and the clientele of the hospitals over time. The hospital started as a wholly private-owned enterprise of the EIC where the sailors and soldiers had to pay for treatment, evolving into a partnership between the Company and the public who footed much of the bill for construction. With the military gradually moving out, it has become a wholly state-owned civilian hospital which continues to this day and is free of charge, especially to the poorest of the poor.

The clientele to these hospitals has, therefore, also evolved from exclusiveness to one of being inclusive. From catering to the needs of the English soldiers only, the hospital has seen a remarkable change over time by including the English and the native public.

Conclusion

The first hospital in India has gone through many transitions over time adapting to the existing socioeconomic and political milieu over its long existence. It has been in multiple places, uprooted many times, due to the vagaries of war and constraints of space. Yet it has provided its patients with succour over its long existence whether it be a young English soldier in a far-off land or an Indian native, rich or poor, travelling the length of his country for better treatment.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Dr K.K. Parathan for providing the photographs. Conflicts of interest. None declared

| 1. | Koestler-Grack RA, Goetzmann WH. Vasco Da Gama and the sea route to India. Philadelphia:Chelsea House Publishers; 2006:2. [Google Scholar] |

| 2. | Benevolo L. Architecture of the renaissance. Vol. 1. Philadelphia:Routledge; 2002:432. [Google Scholar] |

| 3. | Mazars G. A concise introduction to Indian medicine. New Delhi:Motilal Banarsidass; 2006:18. [Google Scholar] |

| 4. | Wheeler JT. Early records of British India: A history of the English settlements in India, as told in the government records, the works of old travellers and other contemporary documents, from the earliest period down to the rise of British power in India. London:Trübner; 1878:47–9. [Google Scholar] |

| 5. | Crawford DG. History of the Indian medical services, 1600–1913. London: Thacker; 1914:17. [Google Scholar] |

| 6. | Love HD. Vestiges of old Madras, 1640–1800: Traced from the East India Company’s records preserved at Fort St George and the India Office, and from other sources. Vol. 1. New Delhi:Asian Educational Services; 1996:214, 217, 218, 560, 555–65. [Google Scholar] |

| 7. | Yule H, Burnell AC. Hobson-Jobson: The definitive glossary of British India. London:Oxford University Press; 2013:326–7. [Google Scholar] |

| 8. | Kaplan A, Pease DE. Cultures of United States imperialism. Durham:Duke University Press; 1993:85–96. [Google Scholar] |

| 9. | Love HD. Vestiges of Old Madras, 1640–1800: Traced from the East India Company’s records preserved at Fort St. George and the India Office, and from other sources. Vol. 2. New Delhi:Asian Educational Services; 1996:18, 74, 455, 456, 458–60, 523, 535, 575, 576. [Google Scholar] |

| 10. | Vij K. Textbook of forensic medicine and toxicology. Principles and practice. 6th ed. Gurugram:Reed Elsevier India; 2014:3. [Google Scholar] |

| 11. | Jaques T. Dictionary of battles and sieges: A guide to 8500 battles from antiquity through the twenty-first century. Miegunyiah Press; 2007:614. [Google Scholar] |

| 12. | Muthiah S. Record of the First City of Modern India. Chennai, India:Palaniappa Brothers; 2008:314. [Google Scholar] |

| 13. | Love HD. Vestiges of Old Madras, 1640–1800: Traced from the East India Company’s records preserved at Fort St. George and the India Office, and from other sources. Vol. 3. New Delhi:Asian Educational Services; 1996: 34–8, 320–33. [Google Scholar] |

| 14. | Chakrabarti P. Medicine & Empire: 1600–1960. Basingstoke:Palgrave Macmillan; 2014:106–7. [Google Scholar] |

| 15. | Madras Tercentenary Celebration Committee. The Madras Tercentenary Commemoration Volume. Chennai:Madras Tercentenary Celebration Committee. New Delhi:Asian Educational Services; 1994:53–60. [Google Scholar] |

Fulltext Views

15,031

PDF downloads

899