Translate this page into:

Indian healthcare at crossroads (part 3): Quo vadis?

Corresponding Author:

A C Anand

Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Kalinga Institute of Medical Sciences, Bhubaneswar, Odisha

India

anilcanand@gmail.com

| How to cite this article: Anand A C. Indian healthcare at crossroads (part 3): Quo vadis?. Natl Med J India 2019;32:175-180 |

Introduction

The previous two articles in this series described how the doctor-patient relationship has deteriorated in India over the past three decades.[1],[2] They also analysed how some factors beyond the conduct of an individual doctor have contributed to the weaken- ing of the relationship. Since the doctor-patient bond forms the bedrock of healthcare? its corrosion has led to a general perception that the quality of medical care in India has deteriorated? whereas in recent years, medical science has made major strides not only in curing diseases but also in reducing suffering due to illness. We have been able to eradicate dreaded diseases such as smallpox and polio in India? which is no mean achievement. As the two articles pointed out, doctors, though being the key providers of healthcare delivery, have neither overall responsibility nor full control over the healthcare delivery system.

The concept of ‘healthcare delivery’, especially at the population or country level, is a much broader construct—whose determinants extend far beyond doctors? doctor-patient relationship and hospitals. It may help to assess what ‘healthcare’ entails? and who is primarily responsibile for its planning. Is it every individual’s right or is it a purchasable commodity that depends on their capability to pay? WHO advocates the former when it states: ‘The enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of health is one of the fundamental rights of every human being? without distinction of race, religion, political belief, economic or social condition.‘[3] Let us look at the situation in India.

Is ‘Right to Healthcare’ A Fundamental Right Under the Constitution of India?

Part III of the Constitution of India houses the ‘Fundamental Rights’, which guarantee all Indian citizens some specific civil rights. These rights include the right to life, the right to equality, the right to free speech and expression, the right to freedom of movement, the right to freedom of religion, which in conventional human rights language may be termed as civil and political rights. However? this list does not include the ‘right to health’.[4],[5]

In the section on ‘Right to Freedom’ (covered by Articles 19-22), Article 21 specifies: ‘No person shall be deprived of his life or personal liberty except according to procedure established by the law.' Though this article does not make a specific reference to health? the Supreme Court of India (SCI), in a catena ofjudgments, has expanded the scope of this article--to include the right to a healthy life, or the right to healthcare.

In a judgment in the case of Paschim Bengal Khet Mazdoor Samiti v. State of West Bengal delivered in 1996,[6] the SCI placed the onus of providing healthcare to the citizens on the State. In another case of Pandit Parmanand Katara v. Union of India[1], the Court expanded the scope of this onus to cover even private clinics and nursing homes, by stressing that no legal or other formality would take precedence over saving the life of an individual. In the case of The Consumer Education and Resource Centre v. Union of India,[8] the SCI reiterated? even more clearly, that ‘the right to health and medical care’ is a fundamental right under Article 21 of the Constitution, stating that '… we hold that right to health, medical aid to protect the health and vigour to a worker while in service or post retirement is afundamental right under Article 21, read with Articles 39(e), 41, 43, 48A and all related Articles and fundamental human rights to make the life of the workman meaningful and purposeful with dignity of person.'

Thus, according to the SCI, the ‘Right to life’ in Article 21 of the Constitution of India includes the protection of health and strength of the worker. The expression ‘life’ in Article 21 does not connote a mere animal existence. In the case of Kirloskar Brothers Ltd v. ESI Corporation 1996[9] too, the SCI held that ‘right to health’ is a fundamental right of the workmen. It also held that this right is enforceable against not only the State but even a private industry. In the case of Bandhua Mukti Morcha v. Union of India 1983[10], the SCI observed that the right to live with human dignity enshrined in Article 21 of the Constitution of India is derived from the Directive Principles of State Policy, and therefore includes protection to health. In the case of Vincent Panikulangara v. Union of India 1987[1] the SCI opined that ‘maintenance and improvement of public health have to rank high. Attending to public health in our opinion, therefore is of high priority— perhaps the one at the top’. These observations of the Court make it clear that healthcare is a fundamental right of every citizen of India and the onus of providing it lies on the State, especially if an individual cannot afford it.

Paradox in Indian Healthcare: Recognition of Citizen’S Right Versus Its Implementation

Despite unambiguous rulings of the highest court of the land conferring the right of healthcare on all citizens, the implementation of this right at the ground level has had several basic flaws. Recognizing the imperative of delivering healthcare, the governments—both Central and state—have created a huge tiered infrastructure extending to the village level. However, various organizations under the infrastructure have failed to efficiently deliver healthcare to the population. One reason is the low level of spending by the government on running the infrastructure— only 1% of the GDP,[12] which is among the lowest in the world. Consequently, the out-of-pocket expenditure (met with by individual citizens) as a proportion of the total health expenditure was as high as 65% in 2015.[13]

One must also differentiate between healthcare and medical care, which are sometimes used as synonyms. ‘Healthcare’ refers to a comprehensive womb-to-tomb care, which ensures that every person has a healthy environment to flourish, adequate measures are taken against most preventable diseases and the public is educated about healthy habits. On the other hand, ‘medical care’ means treatment of the sick. Medical care, thus, is a subset of healthcare, and a small one. The distinction is important because private players provide only medical care--for profit. They have hardly any interest in improving the health of the community and in pursuing other ‘healthcare’ activities. Provision of such activities remains the concern and duty of national governments. Provision of clean drinking water to every household remains a dream in the year 2020. The huge population remains a challenge. Despite the recent initiatives of Swachh Bharat Abhiyan and Intensified Mission Indradhanush, there is a need for a strong commitment for action and additional funding to improve the determinants of health.

The government has also taken some steps to improve medical care. It has set up some model clinical institutions in the public sector. However, these institutions are unable to keep pace with the growth in the population, the ageing elderly and increasing complexity of medical care delivery. Further, the government has also encouraged the growth of private sector hospitals.

Fundamental Right to Health (And Medical Care) Versus the Growth of the Private Sector

Emergency medical care

With the gross shortage of beds and facilities in public sector hospitals, the government has enacted laws (various Clinical Establishment Acts [CEAs]), which place the onus of providing medical care to the public on private hospitals too. At present, any person or organization running a private hospital has the statutory obligation to provide all care in an emergency (i.e. till stabilization of the patient). However, these statues do not contain any provision for reimbursement of the cost incurred in providing such care or stabilization if the patient is unable to pay. It seems unfair to expect private hospitals, created with an intent to earn money, to routinely fund treatment of non-paying patients. Some CEAs put an obligation that private hospitals can be penalized not only for medical errors and hospital-acquired infections,[14] but also for not taking in non-paying patients in emergency!

More importantly, no attempt has been made to clearly define words such as ‘emergency’ and ‘stabilization’. Even where such attempts have been made, e.g. the triage guidelines used in developed countries, the definitions have been found not to be sufficiently sensitive to identify patients who really need emergency care and it has been felt that such guidelines may jeopardize the health of some patients.[15] A patient can perceive any symptom as an emergency, and he may not feel stabilized till all the symptoms go away. Hence, under the CEAs, everyone who considers he has an emergency can believe that private institutions are mandated to provide him free care, or to face penalties or court cases, or both. Let us look at an analogy. The government can expect a private airlines to help in evacuating Indians caught in a foreign country in an emergency situation, such as a sudden war, once in a while— ideally with reimbursement from the government.[16] However, if the private airlines in the country were expected to ferry all or most poor Indians free every day, will these be able to survive, The situation is no different for private medical establishments.

The Law Commission of India, in its 201st report in 2006,[17] was the first to moot the idea of mandatory provision of health services in an emergency; however, it stressed on a mechanism to reimburse the private establishments for the treatment provided—something that the state has ignored. The private hospitals, created to earn profit, are therefore opposed to the idea of CEA.[18],[19] They can provide efficient and comprehensive emergency care, but swift and complete reimbursement of the costs incurred must be ensured.

Non-Emergency Medical Care

The cost of care in private hospitals in India is perceived as unrealistic. Hence, the government has taken steps to regulate the prices of essential drugs and devices.[20] Unfortunately, corporate hospitals do not always transmit such price cuts to the patients. Several states are trying to regulate how much fee a doctor can charge even in a non-emergency situation. Admittedly, some billing norms of private hospitals do need scrutiny. However, asking specialists to reduce consultation charges is clear discrimination against doctors—since there is no regulation of fees for any other professional group. Regulation of cost of care in private hospitals is a serious matter that needs to be looked into, but realistically, comprehensively and to the satisfaction of all stakeholders. A distinction needs to be made between corporate hospitals and professionals who merely work there.

Today, the medical care sector, perceived by its investors as ‘recession-proof, continues to attract foreign investment. The foreign investors feel that medical care in India is much cheaper than that in the rest of the world, whereas income disparity means that it remains unaffordable for most of the Indian public with low earnings. As a result, private establishments attract foreign medical tourists who pay more, while India as a whole remains deficient of doctors and medical facilities. Thus, the government will need to invest in creating new hospitals in the public sector.

Lack of infrastructure as well as of scrutiny has led to stark divergence in healthcare outcomes across institutions. While private hospitals are nimble and are changing with newer modes of treatment, government hospitals suffer from archaic policies. This needs a relook, especially in terms of the need for additional trained human resource to ensure effective and safe delivery of medical care. Rigid bans on creating new posts due to austerity measures may work for government offices, but not in a dynamically evolving field such as medical care.

How are the Other Countries Coping?

A study of the parameters of healthcare delivery system in 11 commonwealth countries found those in the UK, Australia and the Netherlands to be the best.[21] A similar study by WHO among the 191 member states found France, Italy and San Marino to be top in efficiency while India ranked 112th.[22] Let us look at some of these good healthcare delivery systems around the world.

The National Health Service (NHS) in the UK is a publicly funded national healthcare system. In England, the NHS charges all patients, between 18 and 60 years old, a fixed prescription fee of £8.40 per consultation. Those with certain medical conditions (including cancer) or on the low-income list are exempt. The remaining cost of treatment up to tertiary care is funded by the state through general taxes. Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland do not charge even the prescription fee.[23] While the system is rated very high, people do complain about long waiting lists and inability to see a specialist when needed.

Italy has a somewhat similar system with one of the highest doctor per capita ratios at 3.9 doctors per 1000 patients.[24] In 2005, it spent 8.9% of GDP on healthcare.[25] France, in 2005, spent 11.2% of GDP on healthcare, where most doctors are in private practice; there are both private and public hospitals. Social security consists of several public organizations, distinct from the State government, with separate budgets that refunds patients for care in both private and public facilities. The scheme generally refunds patients 70% of most healthcare costs, and 100% in case of costly or chronic ailments. Supplemental coverage may be bought from private insurers, most of which is non-profit.

Since 2006, healthcare in the Netherlands has been provided by a system of compulsory insurance backed by a risk equalization programme so that the insured are not penalized for their age or health status. This is meant to encourage competition between healthcare providers and insurers. Children under 18 years are insured by the government, and special assistance is available to those with limited incomes. In 2005, the Netherlands spent 9.2% of GDP on healthcare.[26]

The USA stands alone among the developed countries in not having a universal healthcare system. It currently operates a mixed-market healthcare system, with the government (federal, state and local) sources accounting for 45% of healthcare expenditure, and the remainder being shared by private sources.[27]

India, with its low GDP, huge population and the current healthcare spending of only around 1% of the GDP, is a far cry from such systems.

Government Health Schemes

India needs a robust primary healthcare programme. The government wants doctors to be altruistic and work where they are needed on a meagre salary. But the planners and policy-makers need to realize that many doctors have taken hefty education loans to pay large fees of private medical colleges. Those who are financially stable are looking for a better life than villages can offer. To move doctors to villages, we need to incentivize rural postings—either financially, or by giving credit for this in professional advancement, e.g. in getting a postgraduate seat. Using persons in alternate systems of medicine is unlikely to solve the problem.

As long as people in the top echelons of government do not show faith in our own system and use it, the lay public will have scant respect for it. As long as decision-makers have the option of treatment at private hospitals, they will make no efforts to improve the public healthcare system.

The Government of India has launched an ambitious ‘Ayushman Bharat’ scheme.[28] This pioneering initiative provides health cover of up to ₹5 lakh per family per year covering over 10 crore (100 million) families. The scheme needs to be lauded for addressing one of the primary problems of our healthcare system—the rising out-of-pocket expenditure, which pushed more than 55 million Indians into poverty in 2011-12. With about 63% of the population having to pay for their healthcare and hospitalization expenses at present, the scheme is undoubtedly well-intentioned. The government has also committed to implement the two pillars of this scheme, i.e. establishment of 1.5 lakh ‘Health and wellness centres’ to bring healthcare closer home, and the Pradhan Mantri Jan Arogya Yojana (PMJAY). The latter is expected to expand the supply side by improving access to private as well as public healthcare services. It also proposes the creation of a cadre of certified frontline health service professionals called the Pradhan Mantri Arogya Mitras (PMAMs) across the country.

The success of PMJAY is contingent on a close cooperation between the Central and state governments. So far, 32 of 36 states have signed memoranda of understanding with the Centre, and the remaining are expected to come on board. One challenge is that the final dispensing of healthcare will be mostly through state- owned hospitals (apart from all the Centrally-owned AIIMS). The current healthcare infrastructure of the states is grossly inadequate to meet the expectations.[29] The scheme allows the states to contribute funds for insurance; however, this will be at the cost of diverting funds allocated to building healthcare infrastructure-- not a happy outcome. This diversion of funds could be exacerbated by the provision of portable healthcare services in-built into the scheme.

Access to health services varies considerable across Indian states. At the national level, India has 0.62 doctors per 1000 population, compared to the WHO recommendation of 1 doctor per 1000 population. However, several states, e.g. Karnataka, Tamil Nadu, Kerala, Punjab, Goa, and Delhi have more doctors than this norm, with Tamil Nadu and Delhi having 1 doctor for every 253 and 334 persons, respectively—at par with countries such as Norway and Sweden. In comparison, Jharkhand, Haryana and Chhattisgarh have only 1 doctor for every 6000 persons.

The existing health infrastructure in various states is the result of cumulative health spending and investment in skill development over several years. Thus, there is a high degree of correlation between health spending and health performance. According to a report by the NITI Aayog, Kerala, Punjab and Tamil Nadu are ranked at the top in providing healthcare. These states were also the top spenders on health infrastructure from 2004-05 to 201516. In 2004-05, the average per capita health expenditure of the bottom three states was ₹122, being less than half of the average ₹252 of the top spenders. The gap has grown substantially during the past 10 years. The equalization of health expenditure across states is desirable if we have to achieve the national health targets.[30]

The better infrastructure for health in the top-performing states is expected to lead to an influx of patients there. The payment for treatment of such patients will go to these states with already better infrastructure and fuel further development of facilities there-- a kind of transfer of wealth from the states down in the ladder to the ones at the top. The poorer states may end up diverting resources from preventive measures, which are the backbone of public health, towards curative measures—which is not desirable in the long run. This would need to be guarded against.

The basic tenets of Ayushman Bharat-National Health Protection Scheme are commendable; however, their implementation appears problematic. Given the state of primary healthcare in India, we need more schemes such as the Swachh Bharat Abhiyan to contain the spread of diseases.

Some citizens are covered by specific schemes such as the Central Government Health Scheme (CGHS) for employees of the Central government and the Ex-servicemen Contributory Health Scheme (ECHS) for ex-servicemen. These schemes promise the beneficiaries cashless hospitalization as well as outpatient facilities. However, the services provided under these schemes are often less than satisfactory, due to poor management. Several private hospitals have either stopped participating in these schemes or are threatening to do so because of delays in payment. This suggests a need for review.

Now that the poor have been taken care of through Ayushman Bharat and the rich have the capacity to bear their medical exigencies, the NITI Aayog is reportedly considering the setting up of a healthcare system for the middle class, which is ‘sasta, sundar aur tikau’ (inexpensive, beautiful/effective and sustainable).[31] This is a laudable objective. In the meantime, the government could increase the limit for expenditure allowed for income tax rebate for health insurance premiums and allow this to cover all diseases as well as OPD treatment for the middle class.

The Road Ahead

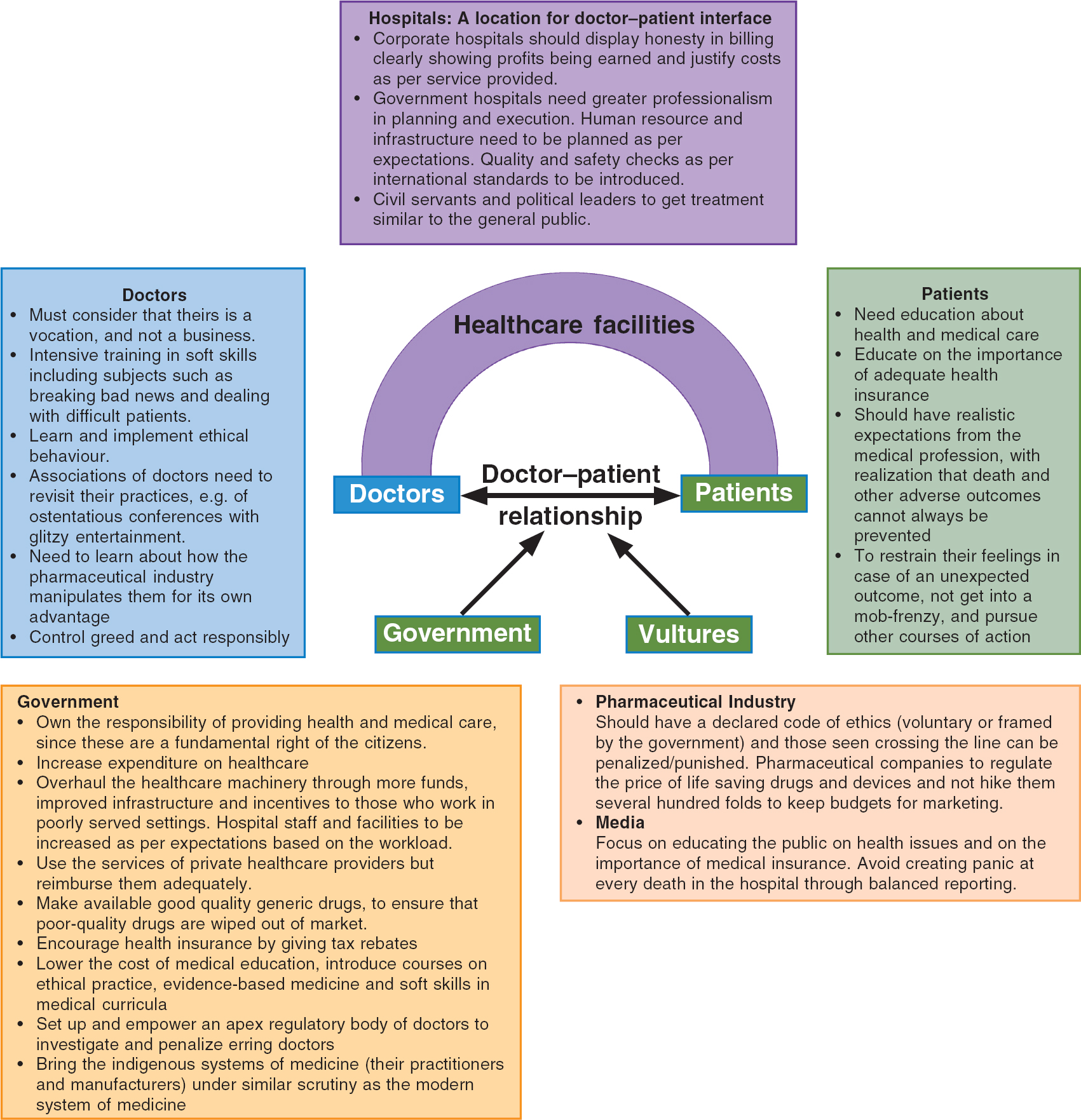

Improvement in healthcare delivery systems and the doctor- patient relationship is crucial for everyone. [Figure - 1] shows how a 360o effort can begin with proactive action by the government. It should own up the responsibility of providing this basic right to citizens as enshrined in Article 21 of the Constitution of India. This will need strengthening of the primary and secondary care in the public sector, involving the private sector in secondary and tertiary care by using health insurance, regulating the activities of doctors and pharmaceutical companies, and guiding the media towards educating masses about realistic expectations from the medical profession. Doctors need training in soft skills and ethical conduct; it is for the government to arrange for and insist on these aspects. Life-saving medicines and devices should be brought in the ambit of price regulation, albeit keeping the prices remunerative. Corporate hospitals must pass on the benefits for such reduction in prices to patients. Above all, there is a need to increase our national health expenditure.

|

| Figure 1: Schema for improvement in healthcare delivery systems and doctor–patient relationship |

Doctors and morality

That doctors come from the same stock as the general public is no defence for some of the immoral things that doctors are accused of doing. Doctors must realize that theirs is a vocation, and not a business. The doctor-patient relationship is built on trust and gaining the trust of our patients is of prime importance to us. Our conduct must be above all suspicion for that trust to be built. Doctors should voluntarily undergo intensive training in soft skills, including in subjects such as ‘how to break the bad news’, ‘how to deal with difficult patients’ and ‘evidence-based care’.

There should be incentives for good ethical behaviour, and punishment for infractions. Various associations of doctors need to revisit their policies of holding ostentatious meetings with glitzy evening entertainment programmes. Doctors need to educate themselves about how the pharmaceutical industry manipulates them. Overall, they need to do what everyone should, i.e. control their greed and act responsibly. A regulatory body with transparent functioning needs to take care of the bad sheep in the profession.

Patients

Patients, or the lay public, cannot generally be said to be wrong. However, the Indian lay public is grossly ignorant about health issues. It needs to learn some basics of health and medical care. An average Indian is ready to spend huge amounts of money on weddings and other celebrations but would not consider buying adequate health insurance.

Their expectations from the medical profession are at times unreal. We must realize that death cannot always be prevented. Relatives of patients will do well to restrain their feelings and not get into a mob-frenzy when medical care results in an unexpected adverse outcome. Other courses of action are available for redressal of their grievances.

Government

The government has a dual role—as an employer of doctors and as a regulator of healthcare delivery. It needs to own the responsibility of providing healthcare and medical care, which are among the fundamental rights of all citizens. Some of the recent efforts noted above are steps in the right direction. However, the general perception is that it is too little and too sluggish, and much more needs to be done.

The government needs to overhaul the healthcare machinery by infusing more funds, improving infrastructure and by giving incentives to those who work in under-served areas. The government hospitals that provide secondary and tertiary care need professionalism in planning and execution. For instance, the human resource and facilities have to be planned as per patients’ expectations. Quality and safety checks need to be introduced as per international standards. Civil servants and political leaders need to be encouraged to receive care and treatment at these very facilities--and in the same manner as the general public gets.

While it is prudent to use private healthcare facilities, the government must reimburse them adequately for providing care to the poor who are unable to pay. Good-quality generic drugs should be made available to make it unviable for those marketing poor quality drugs. Guidelines about cost-effectiveness of various regimes/procedures on the lines of ‘NICE’ guidelines for local conditions should also be formulated. Health insurance should be made attractive by giving tax rebates. Practitioners of and drug manufacturers for indigenous systems of medicine should have similar scrutiny and regulations/standardization as the modern system of medicine. The government can also help by not classifying medical practice as a ‘commercial service’ being rendered to ‘consumers’!

The standards of medical education need attention and curricula should include capsules to inculcate ethical conduct and soft skills. Another factor that needs regulation is exorbitant capitation fees in private medical colleges which makes them look for avenues to earn money rather than excel in academics and profession.

A strong sense of ethics can only be inculcated by extensive training and exemplary disciplinary actions against those found engaging in immoral practices. The government may delegate this activity to an apex regulatory body of doctors, with adequate staff and means to investigate. A good place to begin may be the funding of medical conferences. Some doctors are known to create ‘non-profit’ educational societies for receiving funds from pharmaceutical companies and use the funds for personal ends. Unless doctors’ behaviour is above board, the doctor-patient relationship cannot improve. They should place the highest priority on earning the patient’s trust.

Pharmaceutical industry

For the corrupt medical professionals, the pharmaceutical industry is a partner in crime. In fact, the industry is the one who possibly introduced doctors to unsavoury business practices. It should have a declared code of ethics, and those crossing the line should be penalized. It needs better self-regulation so that the prices of life-saving drugs and devices are not hiked several-fold to provide budgets for unsavoury marketing and the expenditure on marketing activities must be reasonable.

Corporate hospitals

Corporate hospitals provide a stellar service in the treatment of difficult patients and are a force multiplier in the context of limited public hospitals. However, their billing processes need to be transparent, clearly showing profits and justifying costs as per the service provided. At present, corporate hospitals pay private practitioners to get more referrals and encourage ‘cut practice’. If this is unethical for a doctor, it should also be so for a hospital. To discourage such practices, corporate hospitals should be asked to justify costs and show these in their bills for the services rendered. They also need to undertake frequent checks to ensure that proper patient safety and quality procedures are in place.

Media

News media is a powerful tool to educate the public on health issues. However, it must follow a code of ethics to educate the public rather than create panic after every hospital death. In case of an unexpected death, an inquiry by a team of independent senior doctors can be commissioned to decide on whether there was negligence and whether someone needs to be disciplined.

Conclusions

The doctor-patient relationship forms the bedrock of medical care. Doctors need to work actively to reclaim the patients’ trust. The State has the responsibility of providing healthcare and medical care, since these are ‘fundamental rights’ of every citizen. The government should proactively work towards a comprehensive plan for improving primary and secondary care to all at an affordable cost. Government hospitals need to upgrade their facilities and processes to improve patient safety and satisfaction. All segments of the population need the provision of tertiary care, irrespective of their paying capacity. This can be done through special schemes for the poor such as the PMJAY, increased health insurance coverage for the rich, and a judicious combination of these for the middle classes--with a large share of care provided by private hospitals. Health budget spending, a measure of the importance that the State gives to the health of its citizen, needs to be increased to more realistic levels. The pharmaceutical industry and corporate hospitals need to establish and follow codes of ethical conduct and reduce spending on marketing. The media needs to contribute by focusing on appropriate health education to the public than on sensationalizing healthcare stories.

| 1. | Anand AC. Indian healthcare at crossroads (Part 1): Deteriorating doctor-patient relationship. Natl Med J India 2019;32:41-5. [Google Scholar] |

| 2. | Anand AC. Indian healthcare at crossroads (Part 2): Social and environmental influences. Natl Med J India 2019;32:109-12. [Google Scholar] |

| 3. | Hendriks A. The right to health in national and international jurisprudence. Europ J Health Law 1998;5:389–408. doi: https://doi.org/10.H63/15718099820522597 [Google Scholar] |

| 4. | Constitution of India. Available at www.india.gov.in/sites/upload_files/npi/files/ coi_part_full.pdf (accessed on 8 May 2019). [Google Scholar] |

| 5. | Fundamental rights in India. Available at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ Fundamental_rights_in_India. (accessed on 8 May 2019). [Google Scholar] |

| 6. | Supreme Court of India. Paschim Banga Khet Mazdoorsamity … vs State of West Bengal & Anr on 6 May, 1996. Available at https://indiankanoon.org/doc/1743022/ (accessed on 8 May 2019). [Google Scholar] |

| 7. | Supreme Court of India. Pt. Parmanand Katara vs Union of India & Ors on 28 August, 1989. Available at https://indiankanoon.org/doc/498126/ (accessed on 8 May 2019). [Google Scholar] |

| 8. | Supreme Court of India. Consumer Education & Research … vs Union of India & Others on 27 January, 1995. Available at https://indiankanoon.org/doc/1657323/ (accessed on 8 May 2019). [Google Scholar] |

| 9. | Supreme Court of India. Kirloskar Brothers Ltd vs Employees’ State Insurance Corpn on 24 January, 1996. Available at https://indiankanoon.org/doc/555884/ (accessed on 8 May 2019). [Google Scholar] |

| 10. | Supreme Court of India. Bandhua Mukti Morcha vs Union of India & Others on 16 December, 1983. Available at https://indiankanoon.org/doc/595099/ (accessed on 8 May 2019). [Google Scholar] |

| 11. | Kerala High Court. Dr Vincent Panikulangara vs Union of India. Available at https:/ /indiankanoon.org/doc/178230015/ (accessed on 8 May 2019). [Google Scholar] |

| 12. | The World Bank. Domestic general government health expenditure (% of GDP). Available at https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.XPD.GHED.GD.ZS (accessed on 8 May 2019). [Google Scholar] |

| 13. | The World Bank. Out-of-pocket expenditure (% of current health expenditure). Available at https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.XPD.OOPC.CH.ZS (accessed on 8 May 2019). [Google Scholar] |

| 14. | Kaiser Health News. List: 769 hospitals fined for medical errors, infections, by CMS. Available at www.healthcarefinancenews.com/news/list-769-hospitals-fined- medical-errors-infections-cms (accessed on 8 May 2019). [Google Scholar] |

| 15. | Lowe RA, Bindman AB, Ulrich SK, Norman G, Scaletta TA, Keane D, Washington D, Grumbach K. Refusing care to emergency department of patients: Evaluation of published triage guidelines. Ann Emerg Med 1994;23:286-93. [Google Scholar] |

| 16. | Singh T. In an ‘Airlift’ Like Operation, Jet Airways Helps Evacuate 242 Indian Passengers from Brussels. Available at www.thebetterindia.com/50144/brussels- attack-jet-airways/ (accessed on 8 May 2019). [Google Scholar] |

| 17. | Law Commission of India. 201st report on emergency medical care to victims of accidents and during emergency medical condition and women under labour (draft model law annexed). August 2006. Available at http://lawcommissionofindia.nic.in/ reports/rep201.pdf (accessed on 8 May 2010). [Google Scholar] |

| 18. | Pandey K. Why is private healthcare opposing the Clinical Establishments Act? Available at www.downtoearth.org.in/news/health/why-is-private-healthcare- opposing-the-clinical-establishments-act-59766 (accessed on 8 May 2019). [Google Scholar] |

| 19. | 40000 private hospitals and clinics closed in Karnataka. Available at https:// health.economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/hospitals/40000-private-hospitals- clinics-closed-in-karnataka/61485393 (accessed on 8 May 2019). [Google Scholar] |

| 20. | Dey S. Government notifies 15 medical devices as drugs for price regulation. Available at https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/industry/healthcare/biotech/ pharmaceuticals/government-notifies-15-medical-devices-as-drugs-for-price- regulation/articleshow/59468332.cms?from=mdr (accessed on 25 Sep 2019). [Google Scholar] |

| 21. | Best healthcare in the world population. Available at http://worldpopulationreview. com/countries/best-healthcare-in-the-world/ (accessed on 24 Oct 2019). [Google Scholar] |

| 22. | Tandon A, Murray CJL, Lauer JA, Evans DB. Measuring overall health system performance for 191 countries GPE Discussion Paper Series: No. 30 EIP/GPE/EQC World Health Organization, Geneva. Available at www.who.int/healthinfo/ paper30.pdf (accessed on 8 May 2019). [Google Scholar] |

| 23. | Triggle N. NHS ‘now four different systems’. Available at http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/ hi/health/7149423.stm (accessed on 8 May 2019). [Google Scholar] |

| 24. | OECD Health Data. 2007 Available at www.oecd.org/newsroom/38976551.pdf (accessed on 8 May 2019). [Google Scholar] |

| 25. | Health service/health insurance in Italy. Available at https://web.archive.org/web/ 20110720065219/http://www.ess-europe.de/en/italy.htm (accessed on 8 May 2019). [Google Scholar] |

| 26. | Global Health Observatory data repository. Available at http://apps.who.int/gho/ data/node.home (accessed on 8 May 2019). [Google Scholar] |

| 27. | Health care systems by country. Available at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ Health_care_systems_by_country (accessed on 8 May 2019). [Google Scholar] |

| 28. | Press Information Bureau. Ayushman Bharat for a new India 2022, announced; Two major initiatives in health sector announced; Rs 1200 crore allocated for 1.5 lakh health and wellness centres; National health protection scheme to provide hospitalisation cover to over 10 crore poor and vulnerable families. Available at https://pib.gov.in/newsite/PrintRelease.aspx?relid=176049 (accessed on 8 May 2019). [Google Scholar] |

| 29. | Shukla S, Kumar K. Ayushman Bharat: A critical perspective. Available at www.livemint.com/Opinion/m8C6St66ulRHEgZ2ZBkcnN/Opinion—Ayushman- Bharat-a-critical-perspective.html (accessed on 8 May 2019). [Google Scholar] |

| 30. | Govinda Rao M, Choudhury M. Inter-state equalisation of health expenditures in Indian Union. Available at www.nipfp.org.in/media/medialibrary/2013/08/ Health_Equalization_Final_Report.pdf (accessed on 8 May 2019). [Google Scholar] |

| 31. | NITI Aayog mulls healthcare system for middle class. Available at www.businesstoday.in/current/policy/niti-aayog-mulls-healthcare-system-for- middle-class/story/390562.html (accessed on 18 Nov 2019). [Google Scholar] |

Fulltext Views

1,672

PDF downloads

1,240