Translate this page into:

A need to integrate healthcare services for HIV and non-communicable diseases: An Indian perspective

Correspondence to SANGHAMITRA PATI; drsanghamitra12@gmail.com

[To cite: Chauhan A, Sinha A, Mahapatra P, Pati S. A need to integrate healthcare services for HIV and non-communicable diseases: An Indian perspective. Natl Med J India 2023;36:387–92. DOI: 10.25259/NMJI_901_2022]

Abstract

With the decline in HIV mortality, a concomitant increase in morbidity and death not directly related to HIV has been witnessed. Consequently, many countries especially low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) are now facing the dual burden of HIV and non-communicable diseases (NCDs). 2.3 million people living with HIV in India are at a higher risk of developing NCDs due to ageing, which can be attributed to the additional impact of long-standing HIV infection and the side-effects of antiretroviral therapy. This has led to a rise in demand for a combined health system response for managing HIV infection and co-existing NCDs, especially in LMICs such as India. The health and wellness centres (HWCs) envisioned to provide an expanded range of preventive and curative services including that for chronic conditions may act as a window of opportunity for providing egalitarian and accessible primary care services to these individuals. The reasons for integrating HIV and NCD care are epidemiological overlap between these conditions and the similar strategies required for provision of healthcare services.

INTRODUCTION

Despite a decrease in the overall new infections globally, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection still presents a major challenge among the vulnerable groups worldwide.1 HIV is the chief cause of morbidity and deaths globally with almost 38 million people living with HIV (PLHIV) and more than 1.7 million new HIV cases in 2019. From 2010–19, the HIV epidemic continued to grow with Asia and Eastern Europe witnessing a 72% rise in new HIV infections.2 India reports the third highest HIV infections in the world.3 According to the National AIDS Control Organization (NACO), 2019 estimates, there were 2.3 million PLHIV, with a prevalence of HIV of around 0.22% among those aged 15–49 years.4

Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) associated deaths in India peaked at 25 per million during 2004–05 and declined to 4.43 per million population in 2019.5 Expansion of the use of highly active combination antiretroviral therapy (HAART) is the main reason for the reduction in AIDS-related mortality.6 Scaling of HAART was a crucial turning point in the HIV/AIDS disease with gradual evolution of HIV infection into a chronic non-fatal condition. Immune function restoration and virus suppression to an undetectable level has imparted PLHIV with a life expectancy similar to HIV-negative individuals.7 This has led to emergence of HIV infection as a chronic infectious disease,4 though earlier the diseases were considered to be either infectious or chronic in nature.8

Pari passu with the decline in HIV mortality, a concomitant increase in morbidity and death not directly related to HIV has been witnessed.9 Consequently, many countries especially low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) are now facing the dual burden of HIV and non-communicable diseases (NCDs; Table 1). Thus, there are 2.3 million PLHIV in India who are at a higher risk of developing NCDs due to ageing, additional impact of long-standing HIV infection and the side-effects of ART.10 A previous study conducted among ART centres of Odisha, India observed that the prevalence of multimorbidity (the simultaneous presence of two or more chronic conditions) among PLHIV was around 47.7%. Amid the rise in multimorbidity among PLHIV,11 there has been a rise in the demand for a combined health system response for the management of HIV infection and coexisting NCDs especially in the LMICs such as India.10 The health and wellness centres (HWCs) envisioned with providing expanded range of preventive and curative services including that for chronic conditions may act as a window of opportunity for providing egalitarian and accessible primary care services to these individuals. The reasons for integrating HIV and NCD care are: epidemiological overlap between these conditions and the similar strategies required for provision of healthcare services. However, understanding the complex nature of HIV infection along with social barriers such as associated stigma is important to explore the feasibility of linking PLHIV with their nearest HWCs. We mapped the interface of HIV-AIDS and other NCDs with an aim to guide the policy towards providing PLHIV patients with an integrative primary care.

| Author (year), country | Sample size (no. of PLHIV) |

Prevalence (clinical outcome) % | No. of men | Study design | Outcome | Key highlights |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coelho et al. (2018), Portugal24 | 220 | 3.2 | 133 | Cross-sectional | Diabetes mellitus | High prevalence of diabetes among HIV patients |

| Eckhardt et al. (2012), USA25 |

395 | 5.6 | 306 | Retrospective cross-sectional cohort |

Diabetes mellitus | HbA1c is insensitive, but highly specific screening test for diabetes in HIV patients. The relationship of HbA1c to fasting blood glucose is affected by specific anti- retrovirals. |

| Ji et al. (2019), Germany26 |

63 | 22.2 | 52 | Retrospective longitudinal | Diabetes mellitus | There are changes in the lipid levels of patients undergoing HAART, with the potential risk of dyslipidaemia. |

| Faurholt-Jepsen(2019), Ethiopia27 | 332 | 6.6 | 110 | Cross-sectional | Diabetes mellitus | ART-naive Ethiopian HIV patients had a high prevalence of prediabetes and diabetes, with a poor agreement between HbA1c and oral glucose tolerance test. |

| Anyabolu (2017), Nigeria28 | 393 | 17.6 | 110 | Cross-sectional | Dyslipidaemia | Significant association between dyslipidaemia and CD4 cell count. |

| Francisco et al. (2022), Phillipines29 | 635 | 48.6 | 618 | Cross-sectional | Dyslipidaemia | Dyslipidaemia and hyperglycaemia prevalence was high among PLHIV. Traditionally, HIV and treatment-related factors contributed to its development. |

| Ahmed et al. (2023), USA30 | 756 | 25.7 | NA | Prospective cohort | Dyslipidaemia | Dyslipidaemia and hypertension were the most common comorbid conditions observed among PLHIV |

| Limas et al. (2014), Brazil31 | 333 | 78.9 | NA | Cross-sectional | Dyslipidaemia | Significant association between lipid levels and use of ART |

| Sashindran et al. (2021), India32 | 1208 | 21.3 | NA | Cross-sectional | Metabolic syndrome | Patients on tenofovir-based protease inhibitors have significantly higher prevalence of metabolic syndrome |

| Aouam et al. (2021), Tunisia33 | 70 | 27.1 | 35 | Cross-sectional | Metabolic syndrome | Metabolic syndrome was common among PLHIV on ART |

| Fiseha et al. (2019), Ethiopia34 | 408 | 29.7 | 136 | Cross-sectional | Hypertension | Hypertension was highly prevalent among HIV-infected patients on ART attending a clinic in northeast Ethiopia but was mostly undiagnosed. |

| Mogaka et al. (2022), Kenya35 | 598 | 22 | 299 | Cross-sectional | Hypertension | Prevalence of hypertension was high, affecting nearly 1 in 4 adults, and associated with older age, higher and high low-density lipoproteins. |

| Ahmed et al. (2023), USA30 | 756 | 8 | NA | Prospective cohort | Hypertension | Dyslipidaemia and hypertension were the most common comorbid conditions observed among PLHIV |

| Marcus et al. (2014), USA36 | 24 768 | 1.4 (incidence rate) | NA | Cohort | Stroke | Ischaemic stroke incidence in HIV-positive individuals with high CD4 cell count or low HIV RNA is similar to that of HIV-negative individuals. |

| Rasmussen et al. (2015), Denmark37 | 3765 | 1.8 (incidence rate) | NA | Cohort | Stroke | – |

| Klein et al. (2015), USA38 | 56 274 | 1.4 (incidence rate) | NA | Cohort | MI | Decline in MI rate ratio |

| Rasmussen et al. (2015), Denmark37 | 3765 | 2.02(incidence rate) | NA | Cohort | MI | Smoking cessation could potentially prevent more than 40% of MIs among HIV-infected individuals |

| Lai et al, (2018), Taiwan39 | 26 272 | 0.87(incidence rate) | 26 695 | Cohort | Peripheral artery disease | Compared with the general population, PLHIV had a higher risk of incident coronary artery disease, percutaneous coronary intervention, coronary artery bypass surgery, sudden cardiac death, heart failure and chronic kidney disease, but had a lower risk of atrial fibrillation. |

| Nishijima et al. (2014), Japan40 | 435 | 31.0 | NA | Cross-sectional | NAFLD | The incidence of NALFD among Asian patients with HIV-1 infection is similar to that in western countries. NAFLD was associated with dyslipidaemia, but not with HIV-related factors. |

| Crum-Cianflone et al. (2009), USA41 | 216 | 31.0 | NA | Cross-sectional | NAFLD | NAFLD was associated with a greater waist circumference, low high-density lipoprotein, and high triglyceride levels but not with antiretroviral therapy |

| Lui et al, (2016), China42 | 80 | 28.8 | 75 | Cross-sectional | NAFLD | HIV-monoinfected patients are at risk for liver fibrosis and cirrhosis |

NAFLD non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE, HIV AND ART

India’s disease pattern has observed a marked shift in the past three decades with rise in the morbidity and mortality due to NCDs compared to communicable diseases.12 Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) and diabetes mellitus (DM) are one of the five leading chronic diseases in India. The Global Burden of Disease study projected CVDs as the leading contributor of mortality (34.3%) whereas DM contributed to 3.1% of the total mortality burden. In absolute terms, CVDs and DM are responsible for 4 million deaths annually (as of 2016) with most of these deaths being premature.13

CVD is one such comorbid condition of particular concern due to antiviral drug-induced metabolic changes and HIV accelerated inflammatory process that are known to promote atherosclerosis.9 Both HIV infection and ART have been linked with several metabolic and anthropomorphic alterations that increase the risk of CVD.14 HIV-infected individuals have high levels of inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-6, CD14 and CD163.15 CD163 has been associated with a higher risk of coronary artery inflammation and atherosclerosis. CD16 marker has also been linked with the risk of progression of coronary artery disease.15

Studies report changes in the body fat composition with an increase in the central visceral fat among PLHIV on ART. This is frequently associated with dyslipidaemia and hyper-triglyceridaemia, low high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, reduced insulin sensitivity, obesity and diabetes. These changes resemble metabolic syndrome similar to those observed among HIV-negative individuals. The mechanisms for lipohypertrophy are complex and not known in detail.16 D:A:D (data collection of adverse events of anti-HIV drugs) observed 1.6 deaths/1000 person-years due to CVD among 33 308 PLHIV during a 10-year observation period (1999–2008).12 Ivan et al. in their study among HIV-infected Asian Indians observed that 36% PLHIV had intermediate to high 5-year risk of CVD in 2017.17 According to a study in the USA, PLHIV were at a 1.5 times higher risk of having myocardial infarction compared with HIV-negative adults.15

Prevalence of DM among PLHIV has been reported to range from 2% to 14%.18 It is not clear whether HIV tends to be an independent risk factor for DM, but certain factors such as hepatitis C virus infection, and use of certain drugs such as corticosteroids, antipsychotics, opiate use, etc. may influence the incidence of DM in this population. ART-related lipoatrophy and visceral fat accumulation along with increase in proinflammatory cytokines are other factors that may contribute to DM in PLHIV.18

Along with DM, CVD and myocardial infarction, an increased prevalence of other cardiometabolic conditions such as stroke, insulin resistance and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) has also been observed among PLHIV owing to introduction of combination ART along with ageing. ART accelerates the progression of metabolic complications in PLHIV. Both metabolic risk factors (obesity and insulin resistance) and HIV-related factors (ART and inflammation) play a major role in the pathogenesis of NAFLD. Prolonged exposure to ART may also lead to impaired renal function and bone disease. The mechanism of loss of bone mineral content and aseptic necrosis of femoral head, remains unclear. European AIDS Clinical Society recommends that all PLHIV should be screened for metabolic disease such as dyslipidaemia, DM, hypertension, alteration in body composition, cardiovascular risk and renal function at regular intervals. ART has direct effects on the development of such NCDs among PLHIV. With the arrival of successive generations of ART, side-effects have been reported to be fewer. However, it is the cumulative exposure to ART that leads to metabolic changes, insulin resistance, diabetes and hyperlipidaemia as even small adverse effects might lead to a large burden when the drugs are used for longer duration.15

NON-AIDS DISORDERS

ART helps in partial restoration of the immune function which helps in preventing other comorbid conditions that present and define AIDS. Moreover, several reports suggest that PLHIV who have ART-mediated suppression also present with non-AIDS disorders such as CVDs, liver disorders, cancer, osteopenia or osteoporosis, kidney and neurocognitive diseases that are together known as non-AIDS disorders.13 Persistent inflammation seen in HIV along with increased occurrence of tuberculosis and risk factors such as tobacco smoking have been associated with occurrence of chronic obstructive lung disease in PLHIV.

HEALTHCARE PROVISIONS FOR HIV AND NCDs

The HIV programme in India is based on a longitudinal care model focusing on continuity and retention, routine monitoring and promotion of a healthy lifestyle.19 According to the NACO report, 2019–20, an upward trend has been observed for the PLHIV seeking continued ART leading to viral suppression. In India, as of March 2020, the ART coverage was 63% of the total estimated PLHIV nationally and 53% of the total estimated PLHIV were estimated to be virally suppressed.4,20

Although, India continues its National Programme for Non-Communicable Diseases (NP–NCD), resources to manage NCDs are limited, which may put patients at risk for long-term complications and death compared to those who have access to continuity of care.19 Pati et al. in their narrative review observed various gaps in NCD care in India which includes gaps in the services being provided by health facilities, shortage of human resources, need for capacity building of staff, provider capability, private health sector being preferred, and gaps in programme management and monitoring systems.21 Lack of unified systems across public and private sector creates challenges in patient and data capture resulting in low treatment adherence.12 In a study conducted in southern India, 49.6% of patients were observed to be non-adherent to anti-hypertensive medications.22

Integration of HIV and NCD services: Lessons learnt from other countries

Health systems especially in LMICs lack in identification of at-risk patients and retention of patients for life-long care. However, as HIV and NCDs both demand continuum of care, there lies an opportunity to synergies for patient’s benefits. However, evidence on integrating HIV and NCDs is limited.15 India’s HIV programme at present has no provision for management of NCDs among PLHIV. HIV services are decentralized and vertically delivered.19 These are delivered by task shifting enabling the treatment of large number of patients with limited providers. This approach has proven beneficial as far as retention of patients in the care system.19 In contrast, NCD services are centralized and catered largely by hospitals. Patients often present late with symptoms of complications.11 India’s HIV programme currently has no provisions for collecting data on NCD risk factors or NCDs among PLHIV. Hence, developing an integrated model that can manage NCD in PLHIV with a ‘differentiated’ care approach, i.e. providing different patterns of care to PLHIV according to their needs is integral.

Integration of CVD and HIV have been initiated in East African countries such as Zambia, Kenya, Nigeria, Rwanda and Tanzania, where behavioural screening of CVD and diabetes risk factors were integrated into existing HIV services showing the possibility of such integration.23 However, while addressing integration, care should be taken to not hinder the progress made so far. Along with it, identification of factors that facilitate or hinder integration need to be explored.

THE WAY FORWARD

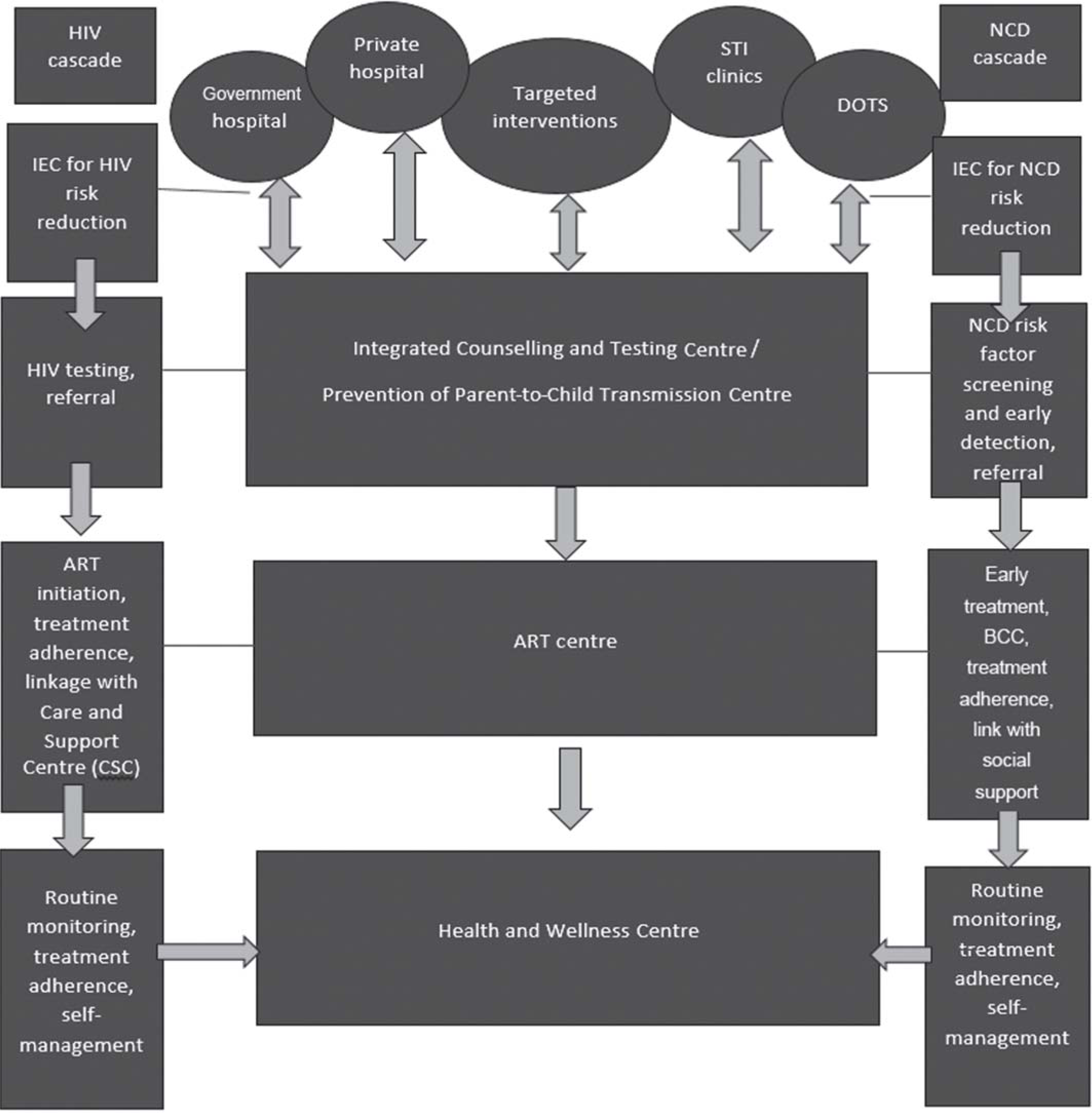

The HIV programme is vertically delivered leading to duplication of services, high opportunity costs for health services and communities, neglect of other health needs and ineffectiveness in optimal usage of resources thus, affecting outcomes. Despite NCDs being recognized as a national health priority by the Government of India, the evidence on the burden of NCDs among PLHIV is evolving. Additionally, integrated management of HIV and associated NCDs is sparse. Leveraging NCD and HIV services into existing primary care could capitalize on the foundation to enhance the quality and efficiency of managing NCDs among PLHIV as resources will be shared instead of siloed. Further, integrating healthcare services for HIV and NCD is the need for countries such as India to develop cost-effective healthcare delivery strategies for its HIV programme as there will be reduced external funding for the HIV programme in future. Thus, integration of services will yield prompt diagnosis, management, referral and linkages of NCDs within the existing care system. Here HWCs may play an important role as these provide a holistic care package, which can help in maintaining continuum of care, screening for opportunistic infections such as candidiasis, maintaining oral health and other healthcare needs (Fig. 1). However, we need to make HWCs friendly for PLHIV so that they can avail services without any fear of being stigmatized. The first and foremost step to overcome stigma in healthcare settings is through awareness regarding HIV along with compliance to universal precautions. Universal precautions will boost the morale and give confidence to healthcare workers. Moreover, breaking stereotypes, developing empathy, building skills to work with stigmatized group, improving patient’s coping mechanism to fight stigma through counselling, and facility restructuring may be useful to address stigma at the healthcare centres. Additionally, healthcare providers especially primary care physicians should be sensitized towards the extra care required both in terms of providing services and emotional support for these patients. HWCs could provide continuity of care as the chronic conditions may require several visits to physicians, routine investigations and long term use of multiple medicines. Furthermore, HWCs may facilitate in seeking coordinated care from various specialists thus, reducing patient’s navigation to several clinics or to a tertiary care hospital. It can also facilitate in de-prescribing of medications, or down as well as up referral of patients as and when required. All medical records of the patients can be maintained through the e-portal which could be used in case of emergency. Wellness activities such as Yoga will help patients in being physically and mentally fit. Nonetheless, teleconsultation services available at HWCs may also be availed if needed. Strengthening HWCs to provide services for PLHIV will be cost-effective for programme managers and at the same time PLHIV will get accessible, affordable and quality services.

- Model depicting integration of HIV care with non-communicable disease (NCD) support and treatment IEC information, education and communication ART antiretroviral therapy STI sexually transmissible infections DOTS directly observed treatment short course BCC behaviour change communication

Conflicts of interest

None declared

References

- The growing challenge of HIV/AIDS in developing countries. Br Med Bull. 1998;54:369-81.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guidelines: Updated recommendations on HIV prevention, infant diagnosis, antiretroviral initiation and monitoring: March 2021 Geneva: WHO; 2021.

- [Google Scholar]

- HIV/AIDS in India: An overview of the Indian epidemic. Oral diseases. 2016;22:10-14.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AIDS mortality before and after the introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy: Does it vary with socioeconomic group in a country with a National Health System? Eur J Public Health. 2006;16:601-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antiretroviral treatment failure and associated factors among HIV patients on first-line antiretroviral treatment in Sekota, northeast Ethiopia. AIDS Res Ther. 2020;17:39.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Integration of HIV and noncommunicable diseases in health care delivery in low-and middle-income countries. Prev Chronic Dis. 2012;9:E93.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HIV infection and cardiovascular disease. Eur Heart J. 2014;35:1373-81.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Integration of noncommunicable disease and HIV/AIDS management: A review of healthcare policies and plans in East Africa. BMJ Global Health. 2021;6:e004669.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence and patterns of multimorbidity among human immunodeficiency virus positive people in Odisha, India: An exploratory study. J Clin Diagn Res. 2017;11:LC10-LC13.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- India Noncommunicable Disease Landscaping, PATH. Available at www.path.org/resources/india-noncommunicable-disease-landscaping/#:~:text=Given%20the%20rise%20in%20the%20noncommunicable%20disease%20%28NCD%29,and%20facilitators%20in%20the%20provision%20of%20NCD%20care(accessed on 7 Dec 2022)

- [Google Scholar]

- Non-AIDS-defining events among HIV-1-infected adults receiving combination antiretroviral therapy in resource-replete versus resource-limited urban setting. AIDS (London, England). 2011;25:1471-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Risk of myocardial infarction in patients with HIV infection exposed to specific individual antiretroviral drugs from the 3 major drug classes: The data collection on adverse events of anti-HIV drugs (D: A: D) study. J Infect Dis. 2010;201:318-30.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The end of AIDS: HIV infection as a chronic disease. Lancet. 2013;382:1525-33.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HIV infection and primary prevention of cardiovascular disease: Lights and shadows in the HAART era. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2016;58:565-76.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardiovascular risk in an HIV-infected population in India. Heart Asia. 2017;9:e010893.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diagnosing and managing diabetes in HIV-infected patients: Current concepts. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;60:453-62.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noncommunicable diseases and HIV care and treatment: Models of integrated service delivery. Trop Med Int Health. 2017;22:926-37.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Integrated HIV testing, prevention, and treatment intervention for key populations in India: A cluster-randomised trial. Lancet HIV. 2019;6:e283-e296.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A narrative review of gaps in the provision of integrated care for noncommunicable diseases in India. Public Health Rev. 2020;41:1-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medication adherence and associated barriers in hypertension management in India. Global Heart. 2011;6:9-13.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Models of integration of HIV and noncommunicable disease care in sub-Saharan Africa: Lessons learned and evidence gaps. AIDS (London, England). 2018;32(Suppl 1):S33-S42.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diabetes mellitus in HIV-infected patients: Fasting glucose, A1c, or oral glucose tolerance test-which method to choose for the diagnosis? BMC Infect Dis. 2018;18:1-3.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glycated hemoglobin A1c as screening for diabetes mellitus in HIV-infected individuals. AIDS patient care STDs. 2012;26:197-201.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Changes in lipid indices in HIV+ cases on HAART. BioMed Res Int. 2019;2019:2870647.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyperglycemia and insulin function in antiretroviral treatment-naive HIV patients in Ethiopia: A potential new entity of diabetes in HIV? AIDS. 2019;33:1595-602.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyslipidemia in people living with HIV-AIDS in a tertiary hospital in South-East Nigeria. Pan Afr Med J. 2017;28:204.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metabolic profile of people living with HIV in a Treatment Hub in Manila, Philippines. A pre-nad post-Antiretroviral analysis. J ASEAN Fed Endocr Soc. 2022;37:53-61.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comorbidities among persons living with HIV (PLWH) in Florida: A network analysis. AIDS care. 2023;35:1053-63.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Analysis of the prevalence of dyslipidemia in individuals with HIV and its association with antiretroviral therapy. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2014;47:547-51.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A study of effect of anti-retroviral therapy regimen on metabolic syndrome in people living with HIV/AIDS: Post hoc analysis from a tertiary care hospital in western India. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2021;15:655-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metabolic syndrome among people with HIV in central Tunisia: Prevalence and associated factors. Ann Pharm Fr. 2021;79:465-72.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hypertension in HIV-infected patients receiving antiretroviral therapy in northeast Ethiopia. Int J Hypertens. 2019;2019:4103604.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence and factors associated with hypertension among adults with and without HIV in western Kenya. PLoS One. 2022;17:e0262400.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HIV infection and incidence of ischemic stroke. AIDS. 2014;28:1911-19.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myocardial infarction among Danish HIV-infected individuals: Population-attributable fractions associated with smoking. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;60:1415-23.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Declining relative risk for myocardial infarction among HIV-positive compared with HIV-negative individuals with access to care. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;60:1278-80.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Incidence of cardiovascular diseases in a nationwide HIV/AIDS patient cohort in Taiwan from 2000 to 2014. Epidemiol Infect. 2018;146:2066-71.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traditional but not HIV-related factors are associated with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in Asian patients with HIV-1 infection. PLoS One. 2014;9:e87596.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) among HIV-infected persons. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;50:464-73.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liver fibrosis and fatty liver in Asian HIV-infected patients. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2016;44:411-21.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]