Translate this page into:

An online course to teach clinical reasoning skills: Students’ perspectives and short-term outcomes

Correspondence to SUNEETHA NITHYANANDAM; suneetha.n.lobo@gmail.com

[To cite: Nithyanandam S, Stephen J, Shankar N, Joseph M, Umesh S, Muralidharan J, et al. An online course to teach clinical reasoning skills: Students’ perspectives and short-term outcomes. Natl Med J India 2025;38:23–9. DOI: 10.25259/NMJI_396_2022]

Abstract

Background

Currently, clinical reasoning (CR) skills are not explicitly taught in the MBBS curriculum. We aimed to assess the effectiveness of an online CR course for final-year MBBS students.

Methods

This was a single-group pre- and post-test study with 57 final-year MBBS students enrolled. Six groups were formed, and one or two faculty facilitators were assigned to each group. A structured format for CR was introduced to the students, and the sessions were designed so that students could sequentially practice the steps using specifically created case scenarios. The students’ CR skills were assessed using a rubric before and after the course. Their confidence levels and perceptions about the course were also obtained. Paired T-test and the Wilcoxon signed rank test were used to assess before and after course differences in the CR abilities and confidence levels, respectively. A thematic analysis of the perceived beneficial aspects of the course and suggested improvements were also done.

Results

The post-course scores were significantly higher than the pre-course scores (p<0.001). The confidence levels of the students for each component of the structured framework for CR showed significant improvement (p<0.001). The structured format used during the course, group activities, case discussions, and the expertise of teachers and course structure were perceived as beneficial. This course could be introduced earlier in the MBBS course with a discussion of more case scenarios.

Conclusions

The online course improved confidence levels and CR abilities of the participants.

INTRODUCTION

Clinical reasoning (CR) is a process through which physicians gather clinical data, process the information, arrive at the most probable differential diagnoses, plan and implement the necessary interventions and evaluate the responses.1 CR goes beyond the initial diagnosis and extends into all aspects of clinical practice and management.

CR is central to the practice of clinical medicine and an essential skill for a physician. CR is not an innate ability but rather a professional skill to be developed. Educators recognise its importance in developing expertise, but it is often not an explicit educational objective.2,3 Instead, it is assumed that this skill will be automatically learnt as the student engages with the curriculum.2

Reasoning through a patient’s presentation is described to occur in one of two processes: system 1-intuitive (non-analytical), fast, used by experts, based on pattern recognition; and system 2-analytical, rational, slower, deliberate, reliable and focuses on hypothetical-deductive reasoning. System 2 is the primary process of reasoning, and the clinician moves towards system 1 reasoning with growing experience.3–5

Traditionally, CR is taught using bedside case presentations/ discussions.6 While more emphasis is given to data gathering during the MBBS course, there is less time spent on understanding the process of clinical reasoning by systematic analysis of data to arrive at a differential diagnosis.7 Several studies have examined the effectiveness of training programmes for improving specific competency in CR. The few studies from India focus on laying the foundations of CR in the first year of the curriculum.8–10 Previous studies from India have shown improvements in CR using methods like SNAPPS and the one-minute preceptor (OMP)11–16 and some studies have used illness scripts to teach CR.17,18 Most have assessed the perception of students about CR.6,19,20 Only some have used tools such as script concordance, Clinical Reasoning Process score and Diagnostic Thinking Inventory to evaluate the understanding and practice of the process.21–23

We aimed to enhance the CR skills among final-year MBBS students through an online CR course using the structured framework for a system 2 approach. The research objectives were: (i) to compare the CR skills of final year MBBS students before and after the online CR course; and (ii) to assess the perceptions of these students about the online CR course.

METHODS

Participants

The study was done in August 2020 on final-year MBBS students. Participation in the course was voluntary. They were required to complete a pre-course assignment, which served as a pre-test and is described later. The students were divided into 6 groups (9–10 in each group), and each group was assigned 1 or 2 faculty facilitators. The students remained in the same group for the entire course duration.

Curriculum

The curriculum consisted of 7 interactive online sessions: (i) overview of CR; (ii) problem list and semantic qualifiers; (iii) problem representation; (iv) CR–differential diagnosis; (v) CR– plan investigation; (vi) case discussion 1; and (vii) case discussion 2.

All the sessions (except the introductory one) followed a similar structure: (i) Review and discussion of the previous session assignment; (ii) introduction to the next topic; (iii) case-based discussion of the session topic; and (iv) another assignment based on the current session topic.

The case scenarios used for the pre-test, post-test, and training sessions all included detailed history and physical examination findings. They were of common medical/surgical problems such as pneumonia, jaundice, headache, acute abdomen, chest pain, stroke, and fever with rash (see Box). A tutor guide was developed for each of the cases to ensure that there was a degree of standardization.

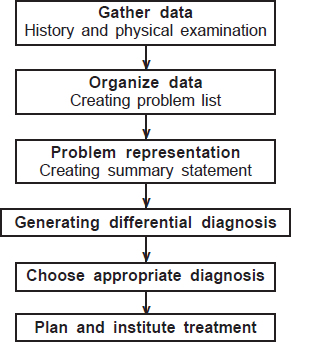

Training method

The CR course focused on organizing data, problem representation, arriving at a differential diagnosis and selecting appropriate investigations (Fig. 1). The participants were introduced to the structured framework approach for CR using the example of the case created for pneumonia. They were then given an assignment where they were instructed to complete the initial steps in the CR process (Table I). The cases assigned to the groups were jaundice, headache, and acute abdomen. Each case was worked on by two groups. The students were expected to individually apply the initial steps of the CR process and come prepared for an online group discussion with team members and assigned faculty facilitators. A faculty-led discussion of the assignment occurred at the start of the following online session for all participants before a new step in the framework was discussed. This process was repeated for the subsequent three sessions. For the last two sessions, all the groups were given two cases of chest pain and stroke, for which they had to apply the steps in the structured framework and discuss them on the lines mentioned previously.

- The structured framework approach used during the course

| Session | Topic |

|---|---|

| 1 | Course outline |

| Clinical reasoning: What it is and why it is important | |

| 2 | Clinical reasoning: The process |

| Assignment 1: Creating a problem list, medicalizing and | |

| applying semantic qualifiers | |

| 3 | Discussion of assignment 1 |

| Assignment 2: Problem representation and differential | |

| diagnosis | |

| 4 | Discussion of assignment 2 |

| 5 | Clinical reasoning: Plan investigations |

| Assignment 3: Plan investigations | |

| 6 | Discussion of assignment 3 |

| Assignment 4: Apply all the steps to 2 case scenarios | |

| 7 | Discussion of assignment 4 |

Evaluation

After the final session, the students had to complete a post-course assignment, which served as a post-test. For the pre-test and post-test, students had to individually create a problem list, medicalise and apply semantic qualifiers, frame a summary statement and suggest the three most probable differential diagnoses with suitable justification. The cases used for the pre- and post-test were pneumonia and fever with rash, respectively. Both the pre- and post-tests were done on Microsoft Teams, and the students were given 24 hours to complete them. An appropriate rubric was used to assess the pre- and post-test (Table II). This rubric was developed by incorporating elements of other available rubrics to assess CR.24–26 For statistical analysis, the pre and post-test scores were converted to percentages.

| Item | Emerging (1 point) | Acquiring (2 points) | Mastering (3 points) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Identifies the pertinent facts of a clinical case | Identifies some of the main problems from the scenario. Does not identify pertinent positives/negatives, risk factors, social/cultural factors, etc. | Identifies most of the problems from the scenario. Begins to identify some of relevant negative positives/negatives, risk factors, social/cultural factors. | Identifies all clinical problems in the scenario including all the relevant positives/negatives, risk factors, social/cultural factors. Omits irrelevant information. |

| Applies medical terms to the problems identified | Does not apply medical terms at all or only minimally. | Applies medical terms to most of the problems identified. | Applies medical terms wherever applicable. |

| Formulates a concise summary statement | Summary statement contains a few pertinent facts and medical terms related to the clinical case. | Summary statement contains many pertinent facts and medical terms related to the clinical case. | Summary statement contains all the pertinent facts and medical terms related to the clinical case. Omits irrelevant information. |

| Develops multiple working differential diagnoses | Proposes one or two differential diagnoses not necessarily the right ones. | Develops multiple working differential diagnoses but not necessarily in the right order. Perseveres in hypotheses despite contradictory evidence. | Develops multiple working diagnoses in a manner that demonstrates an organized approach or structure (e.g. ranks or groups hypotheses by likelihood, risk level, etc.). |

| Provides a rationale for each hypothesis | Provides no or incorrect rationales for most or all hypotheses. | Provides insufficient rationales for hypotheses. Uses opinion or unsupported hunches (faith-based problem solving: ‘I believe…’). | Articulates reasoning by providing a relevant basic science rationale/ explanation for each hypothesis. Usually relates key elements of the case to the differential diagnoses. |

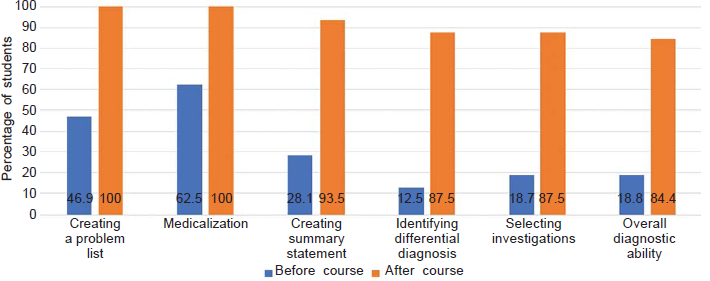

A confidence rating questionnaire and two open-ended questions were also administered to the participants after the course. The confidence rating questionnaire had 6 items related to the CR skills learnt during the course (Fig. 2). The response was on a five-point Likert scale for each item, with one indicating ‘not at all confident’ and five indicating ‘very confident’. The students had to indicate their confidence levels prior to and after the course. The two open-ended questions were ‘Which aspects of the clinical reasoning course were the most useful for your learning? Please explain in as much detail as possible as to why you thought that these aspects were useful’ and ‘Which aspects of the clinical reasoning course do you think could be improved? Please explain in as much detail as possible as to how these aspects could be improved.’ The study received clearance from the institutional ethics committee.

- The confidence of students regarding various components of the clinical reasoning process before and after the workshop. The Y-axis represents the percentage of students who were either confident or very confident. All the differences were significant (p<0.001).

Statistical analysis

The data obtained were analysed both quantitatively and qualitatively. The paired T-test was used to compare the pre-test and post-test scores of the participants. The pre and post-course confidence rating scores were summarised using a bar chart (Fig. 2). The difference between the pre- and post-course confidence rating scores was analysed using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. p<0.05 was considered statistically significant. The statistical analysis was done using SPSS version 16. A thematic analysis of the student’s responses to the open-ended questions was also done.

RESULTS

A total of 57 medical students (20 males and 37 females) from the final year MBBS participated in the course. As 2 students did not submit their post-tests on time, their scores were not included in the analysis. The mean (SD) pre-test and post-test scores were 58.83 (18.74) and 70.47 (20.83), respectively, with a statistically significant improvement in the post-test scores compared to the pre-test scores (p<0.001). Thirty-three students answered the confidence rating questionnaire. The confidence rating scores for their CR ability showed a significant improvement (p<0.001 for all components) following the course when compared to the pre-course rating scores (Fig. 2).

The students’ perspectives about the course were focused on the beneficial aspects of the course and suggestions for improvement. Twenty-eight students provided answers to the open-ended questions. Five themes emerged regarding the beneficial aspects of the course. These were the structured approach to CR, the use of case discussions, working in groups, the expertise of the teacher and course structure. The themes related to the possible improvements to the course were the inclusion of more cases, timing of the course, contact with patients and course structure. Some students felt that the course was fine in the current format and did not require any improvements (Tables III and IV).

| Theme | Description | Quoted student perceptions |

|---|---|---|

| Structured approach to clinical reasoning | The systematic manner emphasized during the course to arrive at a differential diagnosis from the data collected from history and physical examination was appreciated by the students. | ‘The aspect of splitting the process of making a diagnosis into so many parts was a new concept for me which I will surely try to use hereafter. Especially the part of problem list making and summary making were found to be helpful as it laid out a route map for a diagnosis to be made.’ ‘The structured way as to how to approach any case is something which was really useful to me. Initially, before this course, we used to randomly ask for symptoms especially negative history just as part of the process, but now after this course, I feel that we are much clear on what to ask and what’s not needed. Also, writing a summary of the case was really time consuming and difficult for me, but now I feel more confident in writing a short and concise summary.’ |

| Use of case discussions | The process of discussing the case scenario after applying the steps of CR facilitated learning. | ‘Case discussion... Because we have enough knowledge on theory and these cases helped us integrate all that information.’ ‘From what I learned discussing a case is very important and not be biased about any one diagnosis. So maybe focus on that aspect and ask us to read more articles since we students don’t do that much. We are very into our books and that also only one book. But as a whole I really loved the sessions and as a final year student learned what’s important in diagnosing.’ |

| Working in groups | The process of working in groups encouraged students to learn from each other. | ‘The aspect of discussing as a group was very useful because when I discussed my ideas with other people the subject becomes interesting. For example, for the respiratory case discussing examination findings actually made me read through different possibilities and discuss it with others and now I can remember better than before. Discussing DDs’ and ruling out different conditions with others really helps.’ |

| Expertise of teachers | The teachers provided valuable insights into the CR process and acted as role models. | ‘I feel that in the prerequisite form to apply for this course which I had filled, this course had given me all that I expected out of it. I loved the part how different specialty doctors come together to discuss case scenarios of everyday life. And not to mention we got to learn from the best. We covered every system and that was a good overview of how we will face patients in future. Learning the pattern of coming to a diagnosis of a person from different doctors who have devised their own ways have made it much easier for me now to approach a patient.’ |

| Course structure | The choice of cases and assignments contributed to student learning. | ‘It was good to be in groups so we were able to discuss everything during the assignment. The assignments were actually helpful. Thank you.’ |

| Theme | Description | Quoted student perceptions |

|---|---|---|

| Number and type of cases | The students felt that the inclusion of more and varied cases would contribute to the improvement in the course. | ‘I feel more cases could have had been included ... It became a little monotonous in the starting few weeks when we kept discussing the same cases. But thank you so much for the learning.’ ‘I felt maybe more of surgical cases could have also been discussed. Apart from that all other aspects of the clinical reasoning course were good.’ |

| Timing of the course | If the course had been conducted earlier in the MBBS curriculum, it would have been even more beneficial. | ‘Although I enjoyed the course and found it to have helped me increase my knowledge and reasoning skills. I personally felt the course could help a ton more to students who have just entered the clinical side. To help us give a direction on which way to think. Personally I felt the algorithm taught to us during the course can be perfected if we start using it from the time we practice taking clinical cases. Otherwise I felt the workshop was really helpful and do encourage it to be continued’ ‘Personally speaking it is a good approach which has to be taught from the beginning of clinics. During the clinics, I felt that teachers had their own opinion of approach to history taking and examination, it would be appreciated if this technique is taught early on, they’ll have a standardization and decreases confusion. The content of the clinical reasoning course is fine and it is good for a start as approach to clinics.’ |

| Contact with patients | The course would have been even more effective if it had been integrated with clinical postings. | ‘Some demerits I felt was the lack of in person exposure but thanks to Covid-19 we had that issue. Mainly this was my problem, cause clinical exposure and discussion are very different things. So for the future I would just say that our junior batches should be given this amazing course in the hospital setting.’ ‘If it’s possible to include some hands-on experience in any form would be useful, in my opinion. This was obviously not possible during this pandemic time but maybe in future sessions maybe in the form of OPD postings with a consultant or something would be useful. So that we learn how the experienced consultants use all these methods to come up with a diagnosis and work up the patient.’ |

| Course structure | These suggestions were related to the instructional design of the course such as timing of assignments and organization of case discussions. | ‘I would just like add that, the initial few sessions in which the teachers themselves were debating on the summary was bit of confusion to me. I didn’t know whom to follow. So it would be great if the faculty comes to one conclusion which could be then told to the students so that there would be zero confusion. (I know even the faculties were learning but I just wanted to mention this. Secondly, I would ask to spend more time on problem representations and diagnosis approach rather than problem lists and medicalizing terms. Thirdly, it would be great and more beneficial if the assignments to be submitted by each and every student rather than just one from each group. This will definitely make an individual student to work on weaknesses. Fourthly, instead of presenting one case of a group it would be really helpful if the faculty analyze our assignment and then teach us the correct approach in the sessions. That’s all. Thank you.’ |

| No improvements required | A few students felt that the course was good in the current format and did not require improvements. | ‘I feel the workshop is perfect the way it is.’ ‘I cannot think of anything to be improved.’ ‘I think everything was properly organized and good! |

DISCUSSION

CR is an important competency that all doctors should have and is a complex skill to learn. It is, however, not explicitly taught in most medical colleges,27 and it is assumed that students will acquire this skill by increasing their knowledge base and observing teachers.19 During their clinical postings, medical students focus mainly on data gathering from history taking and physical examination. Less emphasis is placed on the analysis of this data systematically to arrive at an accurate differential diagnosis. We aimed to address this gap by conducting a CR course for final-year medical students using a structured framework. The extended lockdown due to the Covid-19 pandemic provided an opportunity to conduct this online course. With the implementation of the new competency-based curriculum (CBC), courses such as these assume even greater importance.

Previous studies from India regarding teaching CR skills have been conducted among first-year MBBS students and postgraduate students.19,23–30 The methods used in these studies, such as SNAPPS and OMP, have been shown to be effective at improving CR abilities.19,26–30 Students need to have the ability to summarise the data collected by history and physical examination for these methods to be effective. The structured framework method used in this study specifically addresses this area. Our study showed that the confidence levels and skills related to CR improved significantly after the course. These findings are similar to other studies where a structured format was used to teach CR.6,18,20,27–31

The participants’ perceptions about the course provided valuable insights that could be used to modify the course in the future. There is a strong case to be made for teaching CR using the structured format when students begin their clinical postings at the beginning of the second year of the MBBS course. This would give students enough time to practice this method until they become proficient in CR. Concurrent faculty development programmes to sensitise all the faculty from clinical departments to integrate this format into routine bedside teaching and clinical assessments would go a long way in ensuring its effectiveness. The methods suggested in the new CBC to develop CR skills, like OMP and SNAPPS, could also be more easily implemented if students already have a grounding in the principles of CR provided by the structured format.32 The students will also learn to embed new knowledge in a clinical situation, which may be more readily retrieved during future clinical encounters.

Our study has some limitations. The assessment tool used in this study was a rubric that provided data about the thought process of the students as they arrived at a differential diagnosis. Other assessment methods, such as the script concordance test, extended matching questions and the key answer test, would have provided more objective evidence about the participant’s ability to make an accurate diagnosis. Only students who volunteered participated in the course. This might have introduced a self-selection bias that could have influenced the results. Our study used a single group before and after study design. A randomized control study design would have been ideal.

Conclusion

We assessed the effectiveness and acceptability of an online CR course for final-year MBBS students. Significant improvements were noted in the confidence and skill levels of the participants related to CR after the course as compared to before the course. The students felt that the structured format for CR, the use of case discussions, the incorporation of group activities, teachers’ expertise, and the course structure facilitated learning. Suggestions for improvement included the discussion of more cases, offering the course earlier in the MBBS programme and integrating the course with regular clinical postings. Our study emphasises the need to incorporate deliberate educational strategies to teach CR skills to MBBS students as they begin their clinical postings. This will contribute to enhancing the quality of the Indian medical graduate and ultimately improve patient care.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We acknowledge the students who were part of this study.

Conflicts of interest

None declared

References

- Clinical reasoning: The core of medical education and practice. Int J Intern Emerg Med. 2018;1:1015.

- [Google Scholar]

- Teaching clinical reasoning to medical students. Br J Hosp Med (Lond). 2017;78:399-401.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Five decades of research and theorization on clinical reasoning: A critical review. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2019;10:703-16.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assessing clinical reasoning: Targeting the higher levels of the pyramid. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34:1631-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deciding analytically or trusting your intuition? The advantages and disadvantages of analytic and intuitive thought. HUPF Economics and Business Working Paper No. 654. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=394920 or

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Teaching clinical reasoning to medical students: A case-based illness script worksheet approach. MedEdPORTAL. 2016;12:10445.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teaching and assessing clinical reasoning skills. Indian Pediatr. 2015;52:787-94.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Infusing the axioms of clinical reasoning while designing clinical anatomy case vignettes teaching for novice medical students: A randomised cross over study. Anat Cell Biol. 2020;53:151-61.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Integrating clinical reasoning principles in case-based learning sessions for first-year medical students: Lessons learned. Res Dev Med Educ. 2019;8:20-3.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Clinically oriented physiology teaching: Strategy for developing critical-thinking skills in undergraduate medical students. Adv Physiol Educ. 2004;28:102-4.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perception of one-minute preceptor (OMP) model as a teaching framework among pediatric postgraduate residents: A feedback survey. Indian J Pediatr. 2018;85:598.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Use of SNAPPS model for pediatric outpatient education. Indian Pediatr. 2017;54:288-90.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SNAPPS facilitates clinical reasoning in outpatient settings. Educ Health Abingdon Engl. 2018;31:59-60.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Effectiveness of SNAPPS for improving clinical reasoning in postgraduates: Randomized controlled trial. BMC Med Educ. 2019;19:224.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Impact of SNAPPS on clinical reasoning skills of surgery residents in outpatient setting. Int J Biomed Adv Res. 2014;5(9) 10.7439/ijbar

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Effectiveness of the 1-minute preceptor on feedback to pediatric residents in a busy ambulatory setting. J Grad Med Educ. 2019;11(4 Suppl):204-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Can clinical case discussions foster clinical reasoning skills in undergraduate medical education? A randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open. 2019;9:e025973.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teaching clinical reasoning to undergraduate medical students by illness script method: A randomized controlled trial. BMC Med Educ. 2021;21:87.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teaching clinical reasoning to medical students. Clin Teach. 2013;10:308-12.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Implementation of a clinical reasoning curriculum for clerkship-level medical students: A pseudo-randomized and controlled study. Diagn Berl Ger. 2019;6:165-72.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Script concordance testing: From theory to practice: AMEE guide no. 75. Med Teach. 2013;35:184-93.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Twelve tips for developing key-feature questions (KFQ) for effective assessment of clinical reasoning. Med Teach. 2018;40:1116-22.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The assessment of reasoning tool (ART): Structuring the conversation between teachers and learners. Diagn Berl Ger. 2018;5:197-203.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The development and preliminary validation of a rubric to assess medical students' written summary statements in virtual patient cases. Acad Med. 2016;91:94-100.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Empirical comparison of three assessment instruments of clinical reasoning capability in 230 medical students. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20:264.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Analysing clinical reasoning characteristics using a combined methods approach. BMC Med Educ. 2013;13:144.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Using illness scripts to teach clinical reasoning skills to medical students. Fam Med. 2010;42:255-61.

- [Google Scholar]

- The effect of short-term workshop on improving clinical reasoning skill of medical students. Med J Islam Repub Iran. 2016;30:396.

- [Google Scholar]

- An analysis of clinical reasoning through a recent and comprehensive approach: The dual-process theory. Med Educ Online. 2011;16

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bridging the gap between the classroom and the clerkship: A clinical reasoning curriculum for third-year medical students. MedEdPORTAL. 2019;15:10800.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- How to develop clinical reasoning in medical students and interns based on illness script theory: An experimental study. Med J Islam Repub Iran. 2020;34:9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]