Translate this page into:

Development of a structured validated module to inculcate research skills in medical undergraduates

Correspondence to TANVI SIDHU; sidhutanvir@gmail.com

[To cite: Sidhu TK, Mahajan R, Kaur D, Bhandari B. Development of a structured validated module to inculcate research skills in medical undergraduates. Natl Med J India 2023;36:374–9. DOI: 10.25259/NMJI_439_21]

Abstract

Background

Evidence-based research aids in decision-making in the health sector for developing health policies for prevention, diagnosis and treatment of diseases. Medical research is not taught in the undergraduate curriculum. Studies show that attributes of research knowledge, awareness and practical involvement in research are low among undergraduate students. We developed and validated a module and trained undergraduate students in research skills through an inter-ventional workshop using the structured module.

Methods

We did this participatory action research with a mixed-methods approach in the Department of Community Medicine at Adesh Institute of Medical Sciences and Research, Bathinda, Punjab. A structured module was developed by the core committee and validated internally and externally. Pilot testing of the module was done by delivering it in the form of a workshop to 46 students. For statistical analysis, percentage agreements, validity indices, median (interquartile range), satisfaction percentages and Wilcoxon sign test were used.

Results

The structured and validated module was established to have high face validity (>90%) and content validity (CVI=0.975). The module was successfully pilot tested for delivery through both onsite and online modes. The satisfaction percentage with the workshop was 91% and 100% and overall rating of the module was 74% and 91% by interns and MBBS students, and 100% by faculty. The scores of knowledge and skills were found to be significantly higher on all variables post workshop with p<0.001. All students scored satisfactory grades for research skills.

Conclusions

Teaching research using a structured validated module improved the knowledge and skills related to research among students. Both students and faculty were satisfied with the use of the structured module.

INTRODUCTION

Even though research is an important component of the curriculum of postgraduate courses, it is not a part of the undergraduate (UG) curriculum in India. With the introduction of the competency-based medical education (CBME) curriculum, elective postings have been introduced, wherein one possible elective to be offered is research. This experience will provide the learner with an opportunity to gain immersive experience of a career stream or research project.1

Inculcation of research aptitude among UGs will not only add to global scientific evidence but also change their outlook and awareness regarding health issues.2 It is also part of the standards set by ‘The World Federation for Quality Improvement in Medical Education’ as well as by various other associations/universities in the field of medicine worldwide.3–6

Studies among UG medical students found that despite some research knowledge, awareness is low and practical involvement in research has been comparatively lower. This can be attributed to barriers such as vast curriculum, inadequate exposure and experience, lack of adequate mentorship, lack of motivation and paucity of funds.

We developed a structured validated module and introduced it for teaching research skills to UG medical students. We also assessed the perception of students and faculty regarding the module and the change if any in the students’ research knowledge and skills after introduction of the research module.

METHODS

We did this participatory action research with a mixed-methods approach in the Department of Community Medicine at Adesh Institute of Medical Sciences and Research, Bathinda, Punjab. The study participants were interns and UG medical students (second phase). All the students of the batches posted during the study period were included.

The required permissions from Research and Ethics Committee were obtained. Informed written consent was obtained.

Development and validation of the module

To decide the contents of the module, inputs were received from students who had completed MBBS on requirements for topics and teaching–learning methodology by e-Delphi, two rounds of which were conducted to develop a consensus. Inputs were received from the Institutional Research Committee members for topics and methodology by focused group discussions.

A core committee (CC) consisting of 11 members was constituted including faculty members from the Department of Community Medicine and fellows of the Foundation for Advancement of International Medical Education and Research (FAIMER) in the institute. The CC was sensitized and individual consent was sought. Each member of the CC was allotted different topics and preliminary drafts were made, which were compiled. This was followed by internal validation of the module by the CC members and compilation by TS. The final module ‘Module for undergraduate medical research’ (MUMR) was sent to 10 experts for external validation (subject experts and FAIMER fellows outside the institute). MUMR was modified according to the feedback received and later on by the CC to suit online delivery. The final module was then shared among resource faculty. The data collection tools consisting of feedback questionnaires and assessment forms were prepared using literature search and validated first by the CC internally and then externally.

The module was tailored to be delivered in 12 hours (excluding assessment). A brief description of the module is provided in Table I.

| Learning objectives | Sub-topics/activities planned | Teaching–learning methods |

|---|---|---|

| At the end of the session, the participant should be able to: | ||

| Session 1: Research in undergraduate phase: Need and benefits | ||

| Define ‘research’ and ‘medical research’; enumerate the advantages of doing research; identify research opportunities for self; explore future avenues | What is medical research?; what do I get?; opportunities of research work in under- graduate period; where do I go next?; reflections | Brainstorming followed by discussion group activity; interactive lecture; powerpoint presentation; case study |

| Session 2: Steps in research | ||

| Discuss the steps in conducting research; plan the steps in conducting research | Generating ideas for steps of research; discussion of research problem and study objectives; discussion of steps of research; reinforcement for steps of research; debriefing and discussion | Think–Pair–Share; participants are paired into groups; discuss the steps with each other and share with larger group; larger group: interactive lecture; participants will work in pairs and will search for missing steps of the research study |

| Session 3: Skills for smooth transition from nurtured undergraduate to self-reliant researcher | ||

| Apply group dynamics; choose a mentor for oneself; develop good communication skills | Group dynamics; mentor–mentee relationship; communication skills; assessment | Game; role play; powerpoint presentation slides, videos; role play |

| Session 4: Identifying a research topic and designing the research question | ||

| Select a research topic; frame a good research question/hypothesis | Generate ideas for research; select a research topic; literature search; frame the research question; debriefing and explaining assessment | Brainstorming: Each participant writes down one idea on a small card; ideas are later displayed and shared on pinboard; group activity: participants are divided into five groups—the group decides on one best idea with supporting points; computer-assisted mentored group task: The group enlists at least two review articles; group activity and group presentation: each group frames its research question/hypothesis fulfilling all elements—group presentation by each group |

| Session 5: Epidemiological study designs in biomedical research | ||

| Enumerate and classify various study designs; identify an appropriate study design for various research questions/scenarios; understand the advantages and limitations of various study designs; calculate and interpret the relevant indices of a study design | Introduction; identifying study designs; observational study; experimental study and various biases; design-based association and causation; parameters/calculations; reflec- tion and debriefing | Brainstorming; case-based discussions; interactive lecture; case-based exercises |

| Session 6: Fundamental biostatistics for biomedical research | ||

| Choose an appropriate sampling technique; calculate sample size; collect relevant data from sampled population; use computer in data handling; present data; analyse data; interpret research data | Introduction to the biostatistics exercise; collection of data and data entering in Excel sheet (master chart); calculation of descriptivestatistics; presentation of data using approinterpret research data priate tables and diagrams; analysis of data using appropriate test of significance; interpretation of data; assessment of students | Case-based exercise |

| Session 7: Ethics in research | ||

| Identify the range of ethical issues that need to be addressed in health research; describe the fundamental ethical principles involving human participants; list key national and inter- national guidelines and regulations that guide the development and review of research studies; recognize the process and issues related to the conduct of health research and practice of medicine | Group activity: Students are divided into five groups of six each for the jigsaw method; Each group will discuss the following topics: (i) Nuremberg code; (ii) Helsinki declaration; (iii) Belmont report: Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences (CIOMS) guidelines; International Council of Harmoni zation; Indian Council of Medical Research guidelines; four basic principles of biomedical research; informed consent; sharing of personal experience of ethics committee functioning;debriefing | Powerpoint presentation; interactive session; role play |

| Session 8: Dissection of a research study/project | ||

| Critically analyse the research work; assess the importance of different parts of a research article | Steps to analyse the research work; allocation of group activity; group activity; debriefing and discussion | Interactive lecture (powerpoint); jigsaw method; interactive lecture |

Administration of the module

This workshop was done by recruiting two groups—(i) interns posted in the department for onsite and (ii) MBBS students of second year for online.

For the onsite workshop: Interns posted in community medicine were briefed through WhatsApp before the start of the workshop. The workshop was conducted for 23 students, 3 hours daily for 4 days after observing social distancing and Covid-19 norms. The MUMR was given to all students as hard copies. Data collection forms were also administered as hard copies and collected back.

For the online workshop: The MBBS students rotating in online clinical classes for community medicine were included in the workshop, 2 hours daily for 6 days, extended by 1 day to complete the delivery. A Google classroom was created to share the resource material and Google forms for data collection. Twenty-three students who attended the entire workshop were considered for data analysis.

The CC were the resource faculty during the workshop. Feedback was collected from the students on the last day of the workshop after explaining about the study and getting written informed consent. The retrospective pre-post self-efficacy questionnaire was administered to students after a briefing, underscoring the importance of honest and critical feedback. The deferred assessment forms were distributed to the students, after explaining the purpose and were asked to be returned after 2 weeks; these were later graded by the faculty. Feedback was collected from the resource faculty and CC using the faculty feedback questionnaire at the completion of the workshop.

Statistical analysis

Data were entered in Microsoft Excel 2010 and the quantitative data were analysed. The validation was done using the item-content validity index (CVI), the criteria-CVI and overall CVI including universal agreement of CVI. The feedback data were subjected to the test of normality to apply the non-parametric tests of analysis. Medians and IQR were calculated for data collected using Likert scales, and satisfaction percentages were calculated. Satisfaction percentage was calculated by dividing the number of respondents agreeing to 4 and 5 of the total responses. The data on retro pre-post self-efficacy was scored on a scale of 1–10 by the participants. Since this was an ordinal scale data, with non-normal distribution, median values were reported and the difference in score was analysed using Wilcoxon sign test.

RESULTS

The validation of the module was done by external experts on face and content validity (Supplementary Tables I and II; available at www.nmji.in).

| Item | Median (Range) | Satisfaction (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interns | UG students | Interns | UG students | |

| Relevance of the workshop | 4 (2–5) | 4 (3–5) | 8 7 | 8 7 |

| Quality of conduct of the workshop | 4 (2–5) | 5 (4–5) | 7 4 | 100 |

| Sequencing of topics | 4 (3–5) | 5 (3–5) | 7 4 | 9 6 |

| Interactive delivery of the workshop | 5 (1–5) | 4 (3–5) | 9 1 | 9 6 |

| Quality of facilitation/guidance provided | 4 (2–5) | 5 (3–5) | 8 3 | 9 6 |

| Resource material provided | 5 (3–5) | 4 (3–5) | 9 6 | 9 1 |

| Assessment methods | 4 (3–5) | 4 (3–5) | 8 3 | 9 1 |

| Overall learning experience | 4 (3–5) | 5 (3–5) | 9 1 | 9 6 |

| Motivation for research work | 4 (2–5) | 4 (3–5) | 8 7 | 9 6 |

| Overall satisfaction with the workshop | 4 (3–5) | 4 (4–5) | 9 1 | 100 |

| Overall rating of the module | 4 (2–5) | 5 (3–5) | 7 4 | 9 1 |

UG undergraduate IQR interquartile range

The face validity was calculated based on the format and presentation of the module. For item 1, 2, 3, 6 and 7 – 100% validation was reported while for items 4 and 5 – 90% validation was reported (Supplementary Table I). Cut-off for face validation was pre-decided at 75%.

The items were rated on a scale of 1 to 4 by the experts (score of 1 not relevant, 2 relevant but major revision required, 3 relevant, needs minor revision, 4 highly relevant and appropriate). The scores of 1 and 2 by the experts were coded into 0 while scores of 3 and 4 were coded as 1. Hence, the final coding given to each item was labelled as either 0 or 1. Mean values for each item was computed to report I-CVI. A total of 20 I-CVI were computed. The criteria used for various items was: <0.70 eliminated; 0.70–0.79 needs revision and >0.80 accepted. The individual I-CVI was 1 for 15 items and 0.90 for the remaining 5 items.

The item index calculated for each item falling under common criteria were compiled to find the mean CVI. So a total of four criteria indices C-CVI were computed. This was calculated as: 0.96, 1, 0.98 and 0.96, respectively for each criterion (Supplementary Table I).

Next, in calculating the overall CVI the means of all C-CVI were used to arrive at overall CVI of the module. The overall module CVI was 0.975.

For calculating the universal agreement, each I-CVI which coded 1 was added and divided by the total number of items. Hence, the universal agreement was 0.75.

After the module workshops, the feedback of the students and faculty were obtained on a Likert scale (range from 1 to 5; Tables II and III). Satisfaction percentage was calculated by dividing the number of respondents agreeing to 4 and 5 of the total responses.

| Variable | Median (Range) |

Satisfaction (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Relevance of the workshop | 5 (4–5) | 100 |

| Sufficient content covered | 5 (3–5) | 9 2 |

| Quality of student–teacher interaction | 4 (2–5) | 8 5 |

| Integration with other departments | 4 (3–5) | 9 2 |

| Teaching methods used | 4 (3–5) | 9 2 |

| Experience with delivery of the module | 4 (3–5) | 7 7 |

| Quality of resource material provided | 4 (3–5) | 8 5 |

| Perception of generation of student motivation/interest in research |

3 (3–5) | 4 6 |

| Overall satisfaction with the workshop | 4 (4–5) | 100 |

| Overall rating of the module | 4 (4–5) | 100 |

IQR interquartile range

The immediate assessment of the students was done by comparing their self-efficacy scores pre- and post-workshop, on five knowledge items and nine skill items (on a scale of 1 to 10). The median values were compared using the Wilcoxon sign test and significant difference was found on all attributes (Table IV).

| Attribute | Interns | Undergraduate students | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median (Range) | p value | Median (Range) | p value | |||

| Pre | Post | Pre | Post | |||

| Knowledge | ||||||

| Awareness of research activities for undergraduates | 1 (0–7) | 8 (3–10) | <0.0001 | 3 (0–8) | 9 (5–10) | <0.0001 |

| Problem identification | 4 (0–10) | 8 (4–10) | <0.0001 | 2 (0–9) | 8 (5–10) | <0.0001 |

| Framing research question | 0 (0–6) | 8 (2–10) | <0.0001 | 0 (0–7) | 8 (4–10) | <0.0001 |

| Understanding study designs | 3 (0–8) | 8 (5–10) | <0.0001 | 3 (0–7) | 8 (4–10) | <0.0001 |

| Steps in research | 1 (0–8) | 8 (6–10) | <0.0001 | 1 (0–7) | 9 (6–10) | <0.0001 |

| Skills | ||||||

| Literature search | 1 (0–6) | 8 (5–10) | <0.0001 | 2 (0–8) | 8 (5–9) | <0.0001 |

| Plan study design | 2 (0–6) | 7 (4–10) | <0.0001 | 2 (0–8) | 8 (5–10) | <0.0001 |

| Protocol development | 3 (0–6) | 8 (2–10) | <0.0001 | 1 (0–7) | 9 (5–10) | <0.0001 |

| Perform statistical operations | 2 (0–8) | 7 (3–10) | <0.0001 | 3 (0–8) | 9 (5–10) | <0.0001 |

| Deal with ethical issues | 4 (0–9) | 8 (2–10) | <0.0001 | 3 (0–7) | 9 (5–10) | <0.0001 |

| Using computers | 6 (1–8) | 8 (5–10) | <0.001 | 5 (2–10) | 8 (4–10) | 0.0001 |

| Project writing | 4 (0–7) | 8 (5–10) | <0.0001 | 2 (0–7) | 8 (4–10) | <0.0001 |

| Working in a team | 5 (0–10) | 9 (1–10) | <0.0001 | 4 (1–8) | 8 (5–9) | <0.0001 |

| Communication skills | 5 (0–10) | 8 (5–10) | <0.001 | 5 (1–7) | 8 (4–10) | <0.0001 |

IQR interquartile range

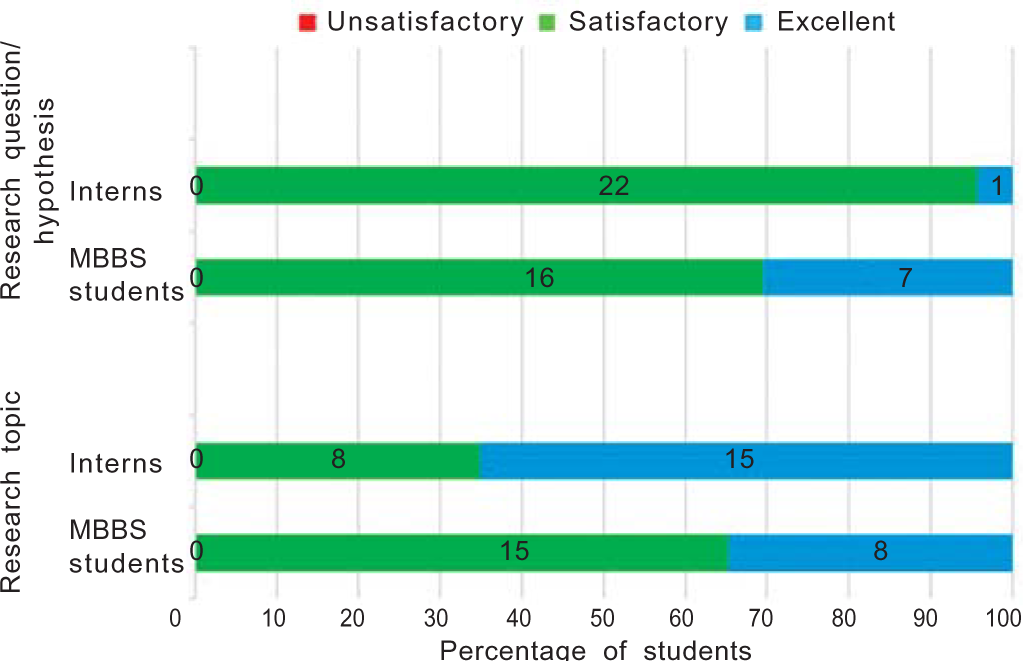

The students were further assessed on two parameters, i.e. selecting the research topic and framing the research question/hypothesis. All students were able to perform satisfactorily in the assessment conducted using the global rating scale by the faculty after 2 weeks (Fig. 1).

- Assessment of students on selection of research topic and framing research question/hypothesis

The preference of students to the timing of the introduction of the module was invariably second phase by both interns and UG students. The preferred mode of delivery for 48% of students was onsite compared to 4% who preferred the online platform. Another 48% suggested that a combination of onsite and online mode can be tried.

DISCUSSION

The MUMR was created for training of UG students in research skills. The module was found to have face validity of >90% and overall CVI was 0.975 and universal agreement of 0.75. The overall satisfaction with the workshop was 91% and 100% for interns and UG students while the overall rating of the module was 74% and 91% by interns and UG students, respectively. The overall satisfaction with the workshop as well as rating of module was 100% by faculty. The scores of knowledge and skills were found to be significantly higher on all variables following the workshop for both interns and UG students. All students scored satisfactory grades for selecting research topics and framing research question/hypothesis on being assessed 2 weeks later by the faculty.

Studies1,7–10 have been conducted globally and in India to explore approaches to inculcate and enhance scientific research skills in UG students. Models for integrating research into the UG curriculum have been tried. Student attitude and experience can be moulded and they can be motivated with short-term research projects, sensitizing workshops and enhanced supervision. To better engage students the following can be used: better learning of research in certain disciplines, development of research skills and techniques, undertaking research-related tasks or engaging in research-based discussions. Mentorship plays a pivotal role in research development in UGs. A study conducted among 40 000 faculty members across various educational institutions in the USA found that more than 50% of them supervised UG students and emphasized the role of independent student research.

Such an approach can be achieved only through implementing training and workshops in UG curriculum.11 Discussion of such projects in terms of lectures regarding study designs and statistics across various years with a final study to be conducted independently during internship has been done by Al Sweleh in Saudi Arabia.9 A similar study was done in India where implementation of a mentored student project programme was discussed across a medical college based in Karnataka.2 Students participating in the programme were successful in developing positive attitudes towards scientific research skills. Additionally, factors such as previous attitudes, perceived quality of supervision and perceived relevance to their professional future can be changed through short-term mentored projects. Another similar project was planned for medical students in Tabuk University, Saudi Arabia.12

We collected students’ feedback and found a high percentage of satisfaction on various variables. The overall satisfaction with the workshop was 91% and 100% for interns and UG students, respectively. The overall satisfaction with the module was 74% and 91%, for interns and UG students, respectively. All the faculty were satisfied with the workshop and the module.

A study in Karnataka among medical UGs found knowledge score regarding the concept of research and its methodology to be 70%. Some of the barriers identified were limited time (59%) and lack of awareness (53%).10

A study done in Gujarat using a two-day workshop was well received and appreciated by students. The students reported satisfaction with mean and median feedback scores of 4 or more out of 5 for most topics. Similar positive and encouraging feedback about including research methodology teaching in the UG curriculum have been received.2,13,14

A one-day workshop on research methodology conducted in Alexandria showed high levels of satisfaction and gain. It was regarded as a valuable, enjoyable experience providing students with both skills and sensitization of benefits and crucial importance to their future medical practice.15

After a research methodology session using a competency-based module in Delhi, about 83% of students were highly satisfied, 61% of students felt motivated to do further research. A qualitative analysis of the feedback showed that students found that the module helped them to enhance their knowledge and develop skills.16 The improvement in knowledge and skills was assessed using retrospective pre-post self-efficacy questionnaire on a score of 0–10. The median and IQR were significantly higher for all criteria post workshop for both the intern and UG students.16

According to the study done in Karnataka, the majority of students reported perceived improvement in research skills with a median grade of 4; 61% of the students wanted the research project to be included as mandatory requirement for completion of MBBS, so as to enhance the importance of these skills.2

In the study done in Delhi, the perceived gain in knowledge and skill was 3 or 4 on a scale of 5 for different components of research.16

A study carried out during research methodology workshop for III MBBS part 1 students in Gujarat, reported mean pre-test and post-test scores of 4.21 and 10.37, showing significant difference at p<0.001. An improvement of 6.16 (146%) was reported.17

A deferred assessment done after 2 weeks of the workshop showed that all students (100%) scored satisfactory grades on both parameters, i.e. selecting research topic and designing research questions for both interns and UG students. About 70% of interns and 78% of UG students preferred that the delivery of this module should be timed in the second phase of MBBS. Regarding the mode of delivery, about half of the students opined that it should be delivered onsite while the other half said that a hybrid approach can be used.

Limitations:

The study was planned to deliver the training in the onsite workshop mode. However, due to Covid-19, the workshop was modified to be delivered in both onsite and online modes. The limited availability of students due to Covid was one limitation, hence the study was limited to only pilot testing on 46 students.

Conclusion

Teaching research using a structured validated module improved research knowledge and skills of UG students. The module can be used effectively for both onsite and online delivery. Both students and faculty were satisfied with the use of the module.

UG students are unaware of and receptive to learning research skills. Teaching of research skills through a structured module-based training using effective teaching–learning methods, early in the UG course can help inculcate and enhance the research aptitude of UG students.

References

- Electives for the undergraduate medical education training program. 2020:1-30. Available at www.nmc.org.in/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/Electives-Module-20-05-2020.pdf (accessed on 29 Jun 21)

- [Google Scholar]

- Fostering research skills in undergraduate medical students through mentored students' projects: Example from an Indian medical school. Kathmandu Univ Med J. 2010;8:294-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Integrating research into dental student training: A global necessity. J Dent Res. 2013;92:1053-5.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medical students' perceptions of an undergraduate research elective. Med Teach. 2004;26:659-61.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Student research projects and theses: Should they be a requirement for medical school graduation? Heart Dis. 2001;3:140-4.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knowledge and attitude of undergraduate dental students towards research. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad. 2018;30:443-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Knowledge, attitudes, and barriers toward research: The perspectives of undergraduate medical and dental students. J Edu Health Promot. 2018;7:23.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Integrating scientific research into undergraduate curriculum: A new direction in dental education. J Health Spec. 2016;4:42-5.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Knowledge, attitude, practice, and barriers toward research among medical students: A cross-sectional questionnaire-based survey. Perspect Clin Res. 2019;10:73-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nurturing research aptitude in undergraduate medical students. J Mahatma Gandhi Inst Med Sci. 2009;14:50-1.

- [Google Scholar]

- A preliminary plan for developing a summer course on practical research engagement for medical students at Tabuk University. J Taibah Univ. 2015;10:79-81.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Evidence-based Medicine (EBM) for Undergraduate Medical Students. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2008;37:764-68.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Students' opinion regarding application of epidemiology, biostatistics and survey methodology courses in medical research. J Pak Med Assoc. 2009;59:307-10.

- [Google Scholar]

- Engaging undergraduate medical students in health research: Students' perceptions and attitudes, and evaluation of a training workshop on research methodology. J Egypt Public Health Assoc. 2006;81:99-118.

- [Google Scholar]

- Development and implementation of a competency-based module for teaching research methodology to medical undergraduates. J Educ Health Promot. 2019;8:164.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assessment of a group activity based educational method to teach research methodology to undergraduate medical students of a rural medical college in Gujarat, India. J Clin Diag Res. 2015;9:LC01-LC3.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]