Translate this page into:

Hydropneumopericardium: A rare complication of pericardiocentesis

Correspondence to AKSHYAYA PRADHAN; akshyaya33@gmail.com

How to cite this article: VOHRA S, PRADHAN A, VISHWAKARMA P, SETHI R. Hydropneumopericardium: A rare complication of pericardiocentesis. Natl Med J India 34:2021;158-60.

Abstract

Hydropneumopericardium is defined as the presence of air and water in the pericardial cavity. Several causes have been postulated which can lead to hydropneumopericardium including trauma, infections secondary to gas-producing bacilli, fistula formation, positive pressure ventilation or even spontaneously without an underlying cause in healthy adults and rarely after pericardiocentesis. We report an uncommon instance of hydropneumopericardium after pericardiocentesis in a 35-year-old man, which developed due to a leaky drainage system. It was immediately drained through the subxiphoid approach under echocardiographic guidance, and the patient was relieved. Hydropneumopericardium is an uncommon but easily diagnosable and avoidable complication of pericardiocentesis. It should be suspected whenever the patient develops increasing dyspnoea following a temporary relief by pericardiocentesis.

INTRODUCTION

Hydropneumopericardium is defined as air and water in the pericardial cavity. Various causes have been postulated for its occurrence and pericardiocentesis is one of them, albeit rare. Hydropneumopericardium can be asymptomatic or symptomatic, when substantial. The patient, most commonly, presents with increasing dyspnoea following temporary relief after pericardiocentesis. As it can potentially lead to cardiac tamponade, it needs to be managed promptly. Hydropneumopericardium can be drained using local anaesthesia through the subxiphoid route under 2-dimensional (2D) echocardiographic guidance. The causes leading to hydropneumopericardium should be sought out to avoid this life-threatening though avoidable pathology.

THE CASE

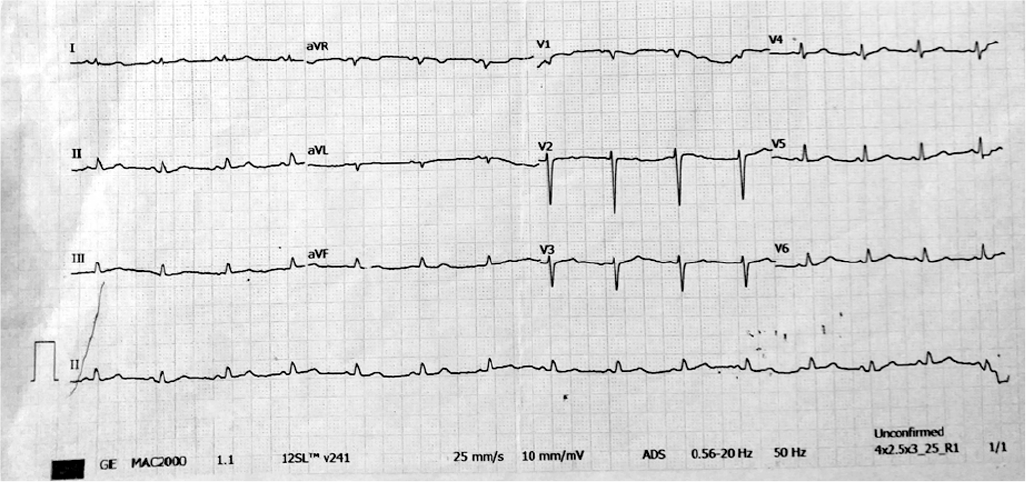

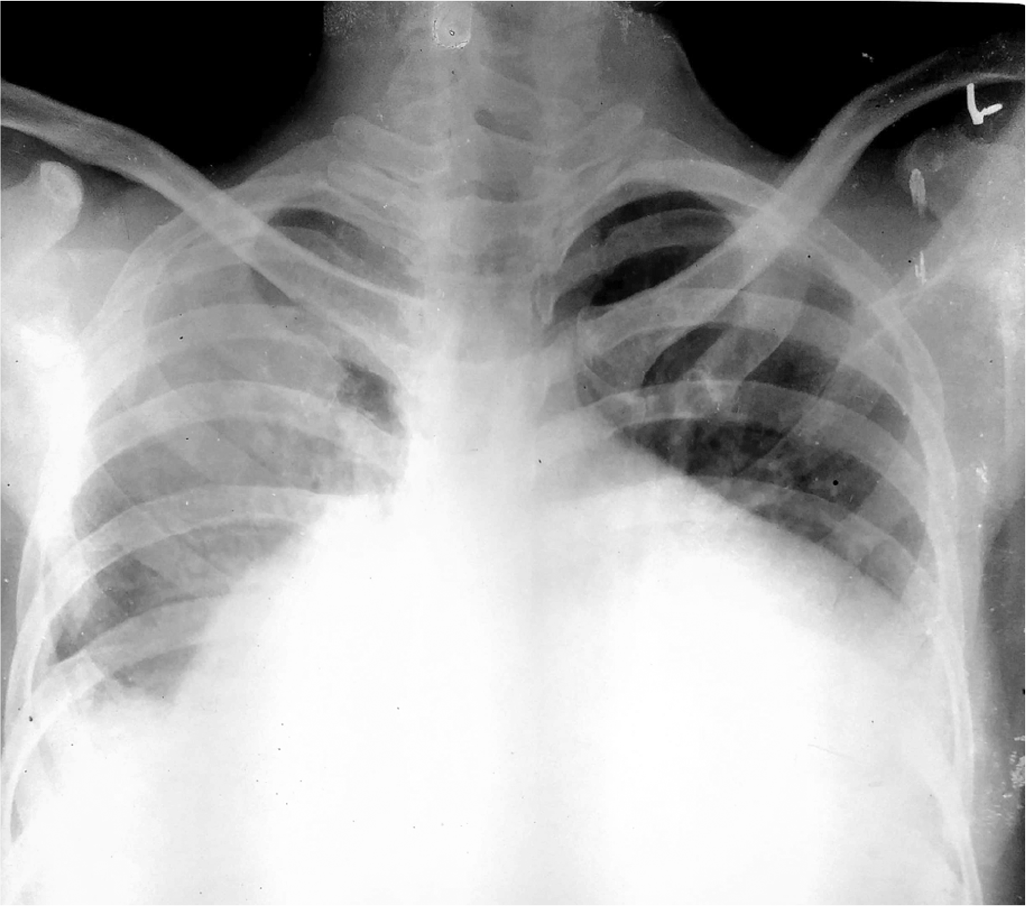

A 35-year-old man was referred to the emergency department with a complaint of low-grade fever for 1 month and progressively increasing dyspnoea for 15 days. On examination, his blood pressure was 84/56 mmHg, pulse rate was 88/minute, on auscultation, the chest had vesicular breath sounds bilaterally with muffled cardiac sounds. Twelve-lead electrocardiography showed low voltage complexes (Fig. 1). Chest X-ray revealed cardiomegaly without any evident pulmonary pathology (Fig. 2). 2D echocardiogram elicited massive pericardial effusion with tamponade physiology. Urgent, echo-guided, subxiphoid, percutaneous pericardiocentesis was performed through a 6 F-single lumen catheter and 1.5 L haemorrhagic fluid was drained with consequent clinical improvement. The patient was relieved of dyspnoea, and the sheath was left in situ. Pericardial fluid was sent for examination and reports showed total leucocyte count of 1250/cmm with 90% lymphocytes, protein 5.9 g/dl, glucose 45 mg/dl, adenosine deaminase enzyme 79 i.u./L, lactate dehydrogenase 459 i.u./L, polymerase chain reaction for tuberculosis was negative, Monteux 5 purified protein derivative was strongly positive, and the Gram and Ziehl–Neelsen stain was negative. Given the high prevalence of tuberculosis in the region, the patient was started on antitubercular therapy. The patient was reviewed for residual fluid twice a day, and by the end of day 3, only minimal pericardial effusion was present and so we planned to take out the sheath the next day before planning discharge.

- Twelve-lead electrocardiogram showing low voltage complexes in limb leads as wells as precordial leads suggestive of pericardial effusion

- Chest X-ray posteroanterior view showing massive cardiomegaly

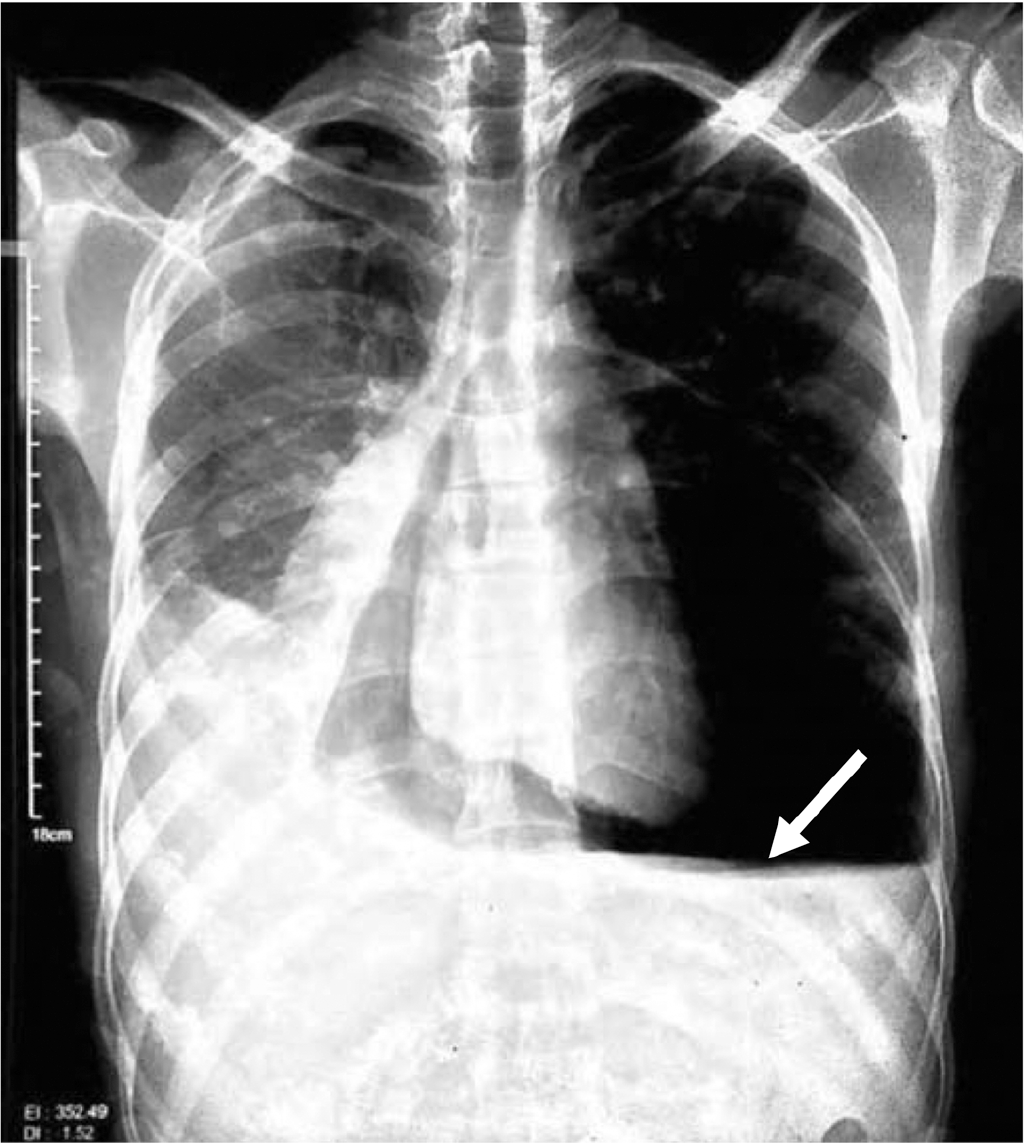

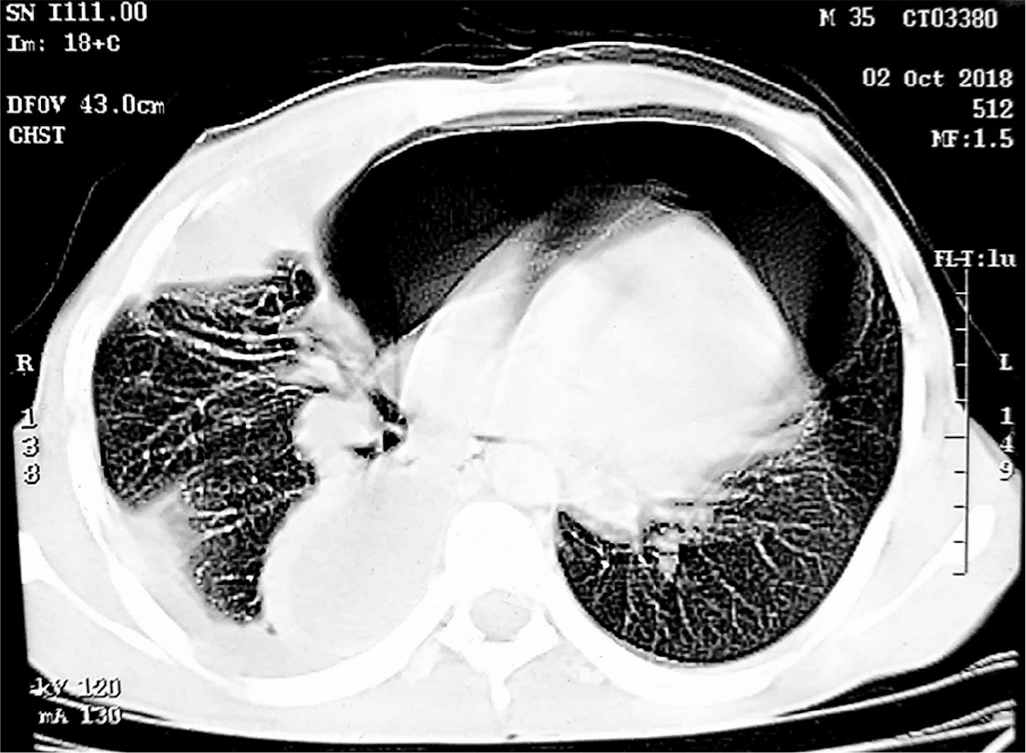

Three days following presentation, the patient complained of dyspnoea and chest pain. The patient’s blood pressure was low and he had tachycardia. A chest X-ray showed hydropneumo-pericardium and mild right-sided pulmonary oedema (Fig. 3). 2D echo showed swirling bubbles in the pericardial cavity. CT scan of the chest confirmed pneumopericardium with an anterior extent (Fig. 4).

- Chest X-ray posteroanterior view showing cardiomegaly secondary to massive hydropneumopericardium with air fluid interface in pericardial space (arrow)

- Axial slice of contrast-enhanced computed tomography thorax of the same patient showing hydropneumopericardium

Approximately 500 ml of pericardial air was evacuated rapidly through the subxiphoid drain, and the catheter was left in situ (Fig. 5). The patient reported improvement in dyspnoea. The patient remained symptom-free subsequently. A repeat 2D echo showed minimal effusion. The hydropneumopericardium was considered to be iatrogenic and the patient was discharged a week later after stabilization.

- Chest X-ray posteroanterior view after drainage of fluid and air. Pigtail catheter can be seen in situ (arrow)

DISCUSSION

Hydropneumopericardium is defined as the presence of air in the pericardial cavity. It can result occasionally after trauma or spontaneously without an underlying cause in a healthy adult and rarely after pericardiocentesis (Table I). It has been attributed either to a direct pleuro-pericardial communication or to an air leakage to the pericardial drainage system.1–4 In our patient, the plausible hypothesis for hydropneumopericardium was a leaky drainage system.

| Trauma: Blunt/penetrating | |

| Pericardial infection | |

| Fistula formation between pericardium and adjacent | |

| air-containing organ | |

| Oesophageal/gastric ulcer | Tuberculosis |

| Achalasia | Subphrenic colonic abscess |

| Pneumonia and abscess | Pulmonary aspergillosis |

| Iatrogenic | |

| Positive pressure ventilation | Post-sternal bone marrow aspiration |

| Laparoscopy | Post-cauterization of oesophageal webs |

| Tracheostomy | Pericardiocentesis |

| Endotracheal intubation | Radiofrequency ablation |

| Thoracocentesis | Insertion of a pacemaker |

| Paracentesis | |

Most of the time iatrogenic hydropneumopericardium requires no specific therapy but in some patients, life-threatening complications, especially pericardial tamponade, can occur and require prompt recognition and adequate management.3,4 Hydropneumopericardium is relatively easy to diagnose by chest X-ray which reveals lucent outline separating the pericardium from the heart or by echocardiography which shows the swirling bubbles sign in the pericardial cavity.3,5,6

The hydropneumopericardium has a variable clinical course and the gravest complication is tension pneumopericardium which can be fatal. It is clear that the abundance and especially the speed of constitution of pneumopericardium are the main determinants of clinical severity that will guide, along with the underlying aetiology, the therapeutic strategy.4–6 In the case of iatrogenic pneumopericardium following pericardiocentesis for pericardial effusion, a re-pericardiocentesis is indicated if the patient is haemodynamically unstable. Watchful waiting for spontaneous absorption of air under close monitoring is indicated in the absence of acute and life-threatening tension pneumopericardium.3,4,7

Both percutaneous and open drainage of the pericardial sac are invasive procedures with the risk of morbidity and mortality. These should be reserved for patients with evidence of haemodynamic compromise attributable to cardiac tamponade. A higher index of suspicion should be maintained in ventilated patients. Tension pneumopericardium mandates drainage of the pericardial sac. This may be achieved through percutaneous or open technique. The subxiphoid approach provides rapid and effective drainage.

Conclusion

Hydropneumopericardium is an uncommon and avoidable complication of pericardiocentesis. It should be suspected whenever the patient develops increasing dyspnoea following a temporary relief by pericardiocentesis. It is easy to diagnose it by chest X-ray as well as 2D echocardiography. When symptomatic, it should be managed by urgent drainage through the subxiphoid route under echocardiographic guidance.

Conflicts of interest

None declared

References

- A case of spontaneous pneumomediastinum and pneumopericardium in a young adult. Korean J Intern Med. 2001;16:205-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pneumopericardium after pericardiocentesis. Int J Cardiol. 2007;118:e57.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pneumopericardium as a complication of pericardiocentesis. Korean Circ J. 2011;41:280-2.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Continuous left hemidiaphragm sign revisited: A case of spontaneous pneumopericardium and literature review. Heart. 2002;88:e5.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bubbles around the heart: Pneumopericardium 10 days after pericardiocentesis. Echocardiography. 2010;27:E115-E116.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardiac tamponade by iatrogenic pneumopericardium. J Cardiovasc Ultrasound. 2008;16:26-8.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Pneumopericardium after pericardiocentesis: A case report. Turk Kardiyol Dern Ars. 2011;39:697-700.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]