Translate this page into:

Identifying Predatory or Pseudo-journals

2 Secretary; World Association of Medical Editors,

Corresponding Author:

Margaret Winker

Secretary; World Association of Medical Editors

margaret.winker@wame.org

| How to cite this article: Laine C, Winker M. Identifying Predatory or Pseudo-journals. Natl Med J India 2017;30:1-6 |

This WAME statement aims to provide guidance to help editors, researchers, funders, academic institutions and other stakeholders distinguish predatory journals from legitimate journals.

Over the past decade a group of scholarly journals have proliferated that have become known as ‘predatory journals’ produced by ‘predatory publishers’. ‘Predatory’ refers to the fact that these entities prey on academicians for financial profit via article-processing charges for open access articles, without meeting scholarly publishing standards.[1] Although predatory journals may claim to conduct peer review and mimic the structure of legitimate journals, they publish all or most submitted material without external peer review and do not follow standard policies advocated by organizations such as the World Association of Medical Editors (WAME), the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE), the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE), and the Council of Science Editors (CSE) regarding issues such as archiving of journal content, management of potential conflicts of interest, handling of errata, and transparency of journal processes and policies including fees. A common practice among predatory publishers is sending frequent e-mails to large numbers of individuals soliciting manuscript submission and promising rapid publication for author fees that may be lower than those of legitimate author-pays journals. In the most egregious cases, they collect publication fees but the promised published articles never appear on the journal website. In some cases, authors publishing in such journals are aware that the journals do not adhere to accepted standards but choose to publish in them anyway,[2],[3] hence they are not ‘prey’. Therefore, ‘pseudo-journals’ may be a more accurate name.

Regardless of the name applied to them, such journals do not provide the peer review that is the hallmark of traditional scholarly publishing. As such, they fall short of being the type of publication that serves as evidence of academic performance that is necessary to gain future research funding and academic advancement. Identifying such journals is important for authors, researchers, peer reviewers and editors, because scientific work that is not properly vetted should not contribute to the scientific record. ‘Pseudo-journals’ include journals that despite being published by legitimate publishers exist solely for marketing purposes;[4] do not provide peer review sufficient to identify ‘fake’ papers;[5],[6] and other questionable practices.[7] Predatory journals are the most prevalent type of pseudo-journals and have increased quickly. A longitudinal study of article volumes and publishing market characteristics estimated 8000 active predatory journals, with total articles increasing from 53 000 in 2010 to 420 000 in 2014 (an estimated three-quarters of authors were from Asia and Africa).[8] Therefore, this statement focuses on predatory journals.

Most academicians (and their affiliated institutions and the entities that fund their work) want their work to be published in legitimate journals. Unfortunately, the tremendous proliferation of journals—both legitimate and predatory—makes it increasingly difficult to identify predatory journals. A journal that an author has never heard of might be a legitimate new journal, a legitimate journal that is well established but is read and cited far less frequently than other journals in the discipline, a journal from a part of the world that the author is unfamiliar with, or a ‘predatory’ journal. Two substantial efforts to assist stakeholders in distinguishing predatory from legitimate journals include the now defunct Beall's List and the Directory of Open Access Journals (DOAJ).

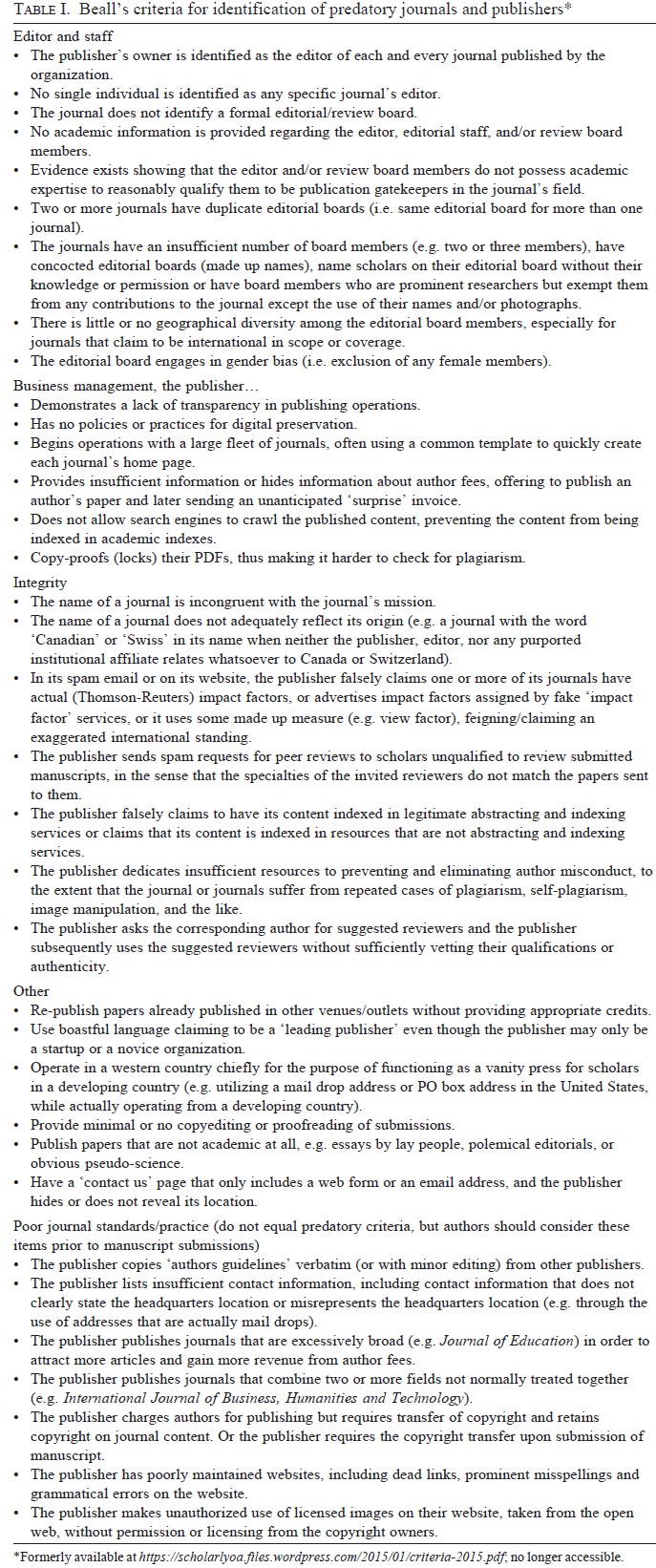

From 2011 to January 2017, Jeffrey Beall, a librarian at Auraria Library and associate professor at the University of Colorado Denver, compiled annual lists of potential, possible or probably predatory scholarly open access journals.[9] In 2015, he added two additional lists—misleading metrics and hijacked journals. The misleading metrics list included companies that produce counterfeit impact factors or similar journal measures that predatory publishers use to deceive scholars into thinking that the journals are legitimate. ‘Hijacked journals’ refer to the creation of a counterfeit website that mimics the website of a legitimate journal for the purpose of soliciting submissions and collecting author fees from authors who believe they are sending their work to the legitimate journal. However, on 17 January 2017, Beall's website was dismantled for unclear reasons.[10] Beall's lists were alarmingly lengthy, with 1155 predatory publishers and 1294 predatory journals being listed as of 3 January 2017. In compiling his list, Beall used criteria [Table - 1] that he based in part on two policy statements—the COPE Code of Conduct for Journal Publishers[11] and the Principles of Transparency and Best Practice in Scholarly Publishing[12] from WAME, COPE, DOAJ, and Open Access Scholarly Publishing Association (OASPA). The effort involved in developing Beall's list was impressive and it was a reasonable starting point for someone who wanted to investigate a journal's or publisher's authenticity. However, Beall did not list the specific criteria he used to categorize a given journal as predatory[13] and he mistakenly black-listed some legitimate journals and publishers, particularly those from low- and middle-income countries (LMICs).[14] He used criteria like ‘journals having little or no geographic diversity on their editorial boards' and ‘not being listed in standard periodical directories or library databases’,[9] problems common for journals in LMICs.[15],[16] In addition, some criticized Beall for being biased against open access publishing models, and for conflating access rules with business models.[17] Other Beall criteria, while identifying potentially undesirable journal features, are not reliable indicators of predatory publication practices (e.g. exclusion of female members on the editorial board). Thus, WAME cautions against the use of prior appearance on Beall's list as the solitary method for determining whether a journal is predatory or legitimate.

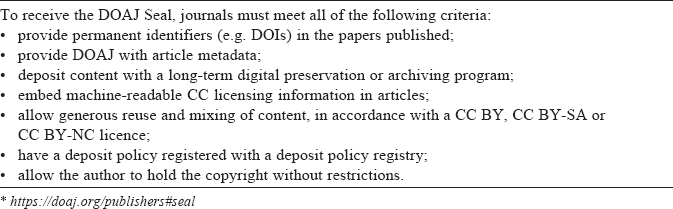

While the purpose of Beall's list was to identify ‘predatory’ journals, the DOAJ has the converse purpose of identifying legitimate open access journals.[18] According to its website, ‘The (DOAJ) is a service that indexes high quality, peer reviewed Open Access research journals, periodicals and their articles' metadata. The Directory aims to be comprehensive and cover all open access academic journals that use an appropriate quality control system … and is not limited to particular languages or subject areas.' As of 5 January 2017, DOAJ included 9456 journals from 128 countries. The DOAJ grants some journals the DOAJ seal, a mark of certification for open access journals for achievement of a high level of openness, adhering to best practices, and having high publishing standards [Table - 2]. However, the DOAJ is not a comprehensive list of all legitimate open access journals and a journal that is not listed should not be assumed to be illegitimate or predatory. It may be a journal that has not sought inclusion on the DOAJ or has insufficient funding to meet some of DOAJ's requirements. Conversely, listing on the DOAJ does not guarantee high quality—the DOAJ has a routine mechanism for users of the DOAJ to notify DOAJ if they find a journal with questionable practices on the DOAJ list.

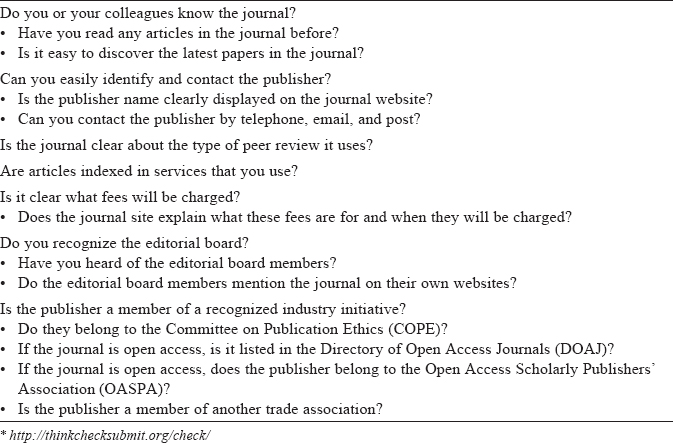

A third approach is the ‘Think. Check. Submit.’[19] checklist developed by a coalition of scholarly publishing organizations. These criteria [Table - 3] are useful for authors considering where to submit their work, but as with the other initiatives are not a failsafe to identify all legitimate scholarly journals. The criterion of knowledge of individuals involved in the journal make this approach less useful for those who are evaluating journals from a different part of the world.

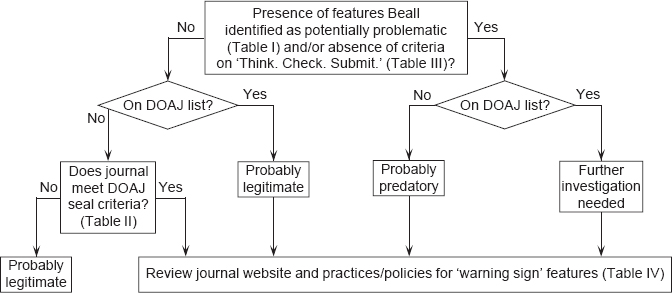

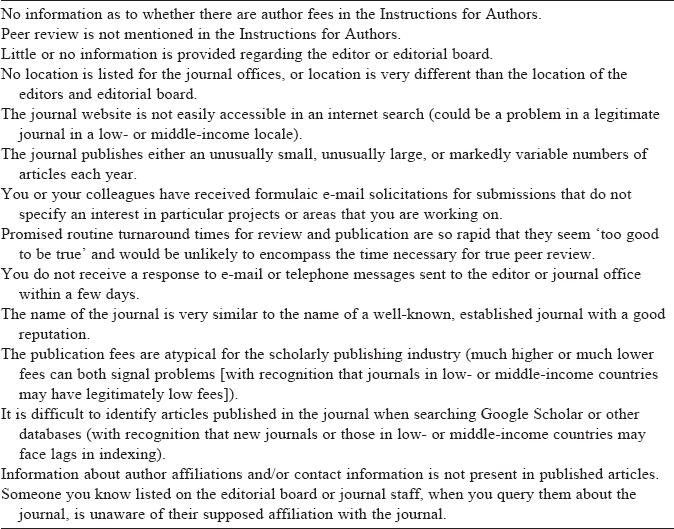

Because existing initiatives do not provide error-proof methods for determining the status of a particular journal, individuals who aim to gain a high level of assurance about a journal's status need to investigate further. WAME developed the framework illustrated in [Figure - 1] for such investigation. This framework begins with assessing whether the journal has any of the characteristics Beall viewed as potentially problematic [Table - 1], its presence in the DOAJ, and presence of ‘Think. Check. Submit.’ features [Table - 3], with further investigation guided by these initial indicators. Assessment remains subjective, but reviewing the journals' website and practices/policies for evidence of the ‘warning sign’ features [Table - 4] will help inform this judgement. The more ‘red flags’ that are present, the more hesitant one should be to consider the journal a desirable publication venue.

|

| Figure 1: Predatory journals algorithm DOAJ Directory of open access journals |

Why have predatory journals become a significant problem? Digital publication brought many benefits, including lowered journal overhead relative to printing and postage, and ‘author pays’ models enabled immediate open access. Nevertheless, scholarly journals pay substantial costs for editor and staff time for manuscript evaluation, peer review, editing, and quality assurance. Predatory journals reduce or eliminate these services, skimming the author fees as profit.

Why have predatory journals thrived? Their promise of quick publication is attractive to academics. Predatory journals provide young researchers who may not know better and academicians in search of quick publication with a low barrier to publication. In too many settings, promotions committees and other such bodies focus on the number of publications rather than the quality of those publications and the venues in which they appear. Thus, predatory journals are likely to continue to prosper unless such bodies and funders begin to routinely scrutinize the quality as well as the quantity of their faculty's publications, not by excluding all online journals from consideration,[20] but by identifying acceptable journals according to quality criteria. Ideally, academic institutions should also identify academics who are listed as editors or editorial board members for journals established as predatory, and require that their affiliation with the institution is removed. Those mentoring junior researchers must recognize that predatory journals exist and help those they mentor identify high quality publication venues. Websites developed to help researchers must be responsible about the journals their resources help promote.[21] Addressing the scourge of predatory journals will require efforts at every level of the research process.

Future initiatives to identify predatory journals should be as transparent and objective as possible, with mechanisms for journals incorrectly identified as predatory to correct the record and for predatory journals to become legitimate by improving their practices. Authors who have submitted their work to predatory journals should share their experiences to ‘out’ poor journal practices. Authors whose legitimate research was published in predatory journals should have a mechanism for submitting their research to a legitimate peer-reviewed journal, preferably after retraction of the ‘predatory’ publication—although, unfortunately, most predatory journals do not publish corrections or retractions. Such initiatives would hasten the demise or conversion of predatory journals.

Acknowledgements

We thank the WAME Board (Rod Rohrich, Lorraine Ferris, Tom Lang, Phaedra Cress, Fatema Jawad, Rajeev Kumar, José Lapeña, Chris Zielinski) and Peush Sahni for their critical review and approval.

| 1. | Clark J, Smith R. Firm action needed on predatory journals. BMJ 2015;350:h210. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h210. Available at www.researchgate.net/profile/Jocalyn_Clark/publication/271022726Firm_action_needed_on_predatory_journals/links/56f8f0cc08ae81582bf40ff0.pdf (accessed on 14 Feb 2017). [Google Scholar] |

| 2. | Wallace F, Perri T. Economists behaving badly: Publications in predatory journals. Munich Personal RePec Archive, 15 August 2016. Available at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/73075/1/MPRA_paper_73075.pdf (accessed on 7 Feb 2017). [Google Scholar] |

| 3. | Seethapathy GS, Santhosh Kumar JU, Hareesha AS. India's scientific publication in predatory journals: Need for regulating quality of Indian science and education. Curr Sci 2016; 111:1759–64. doi: 10.18520/cs/v111/111/1759- 1764. Available at www.currentscience.ac.in/Volumes/111/11/1759.pdf (accessed on 7 Feb 2017). [Google Scholar] |

| 4. | Grant B. Elsevier published 6 fake journals. The Scientist, 7 May 2009. Available at www.the-scientist.com/?articles.view/articleNo/27383/title/Elsevier-published-6-fake-journals/ (accessed on 7 Feb 2017). [Google Scholar] |

| 5. | Bohannon J. Who's afraid of peer review? Science 2013;342:60–5. doi: 10.1126/science.342.6154.60. [Google Scholar] |

| 6. | Davis P. Open access publisher accepts nonsense manuscript for dollars. Scholarly Kitchen, 10 June 2009. Available at http://scholarlykitchen.sspnet.org/2009/06/10/nonsense-for-dollars (accessed on 7 Feb 2017). [Google Scholar] |

| 7. | Eriksson S, Helgesson G. The false academy: Predatory publishing in science and bioethics. Med Health Care and Philos 2016. doi:10.1007/s11019-016-9740-3. [Google Scholar] |

| 8. | Shen C, Bjork BC. ‘Predatory’ open access: A longitudinal study of article volumes and market characteristics.BMC Med 2015;13:230. doi :10.1186/s12916-015-0469-2. [Google Scholar] |

| 9. | Beall J. Beall's list of predatory publishers 2016. Scholarly Open Access. Formerly available at https://scholarlyoa.com/ 2017/01/03/bealls-list-of-predatory-publishers-2017/; now available at https://web.archive.org/web/20170113114519/https://scholarlyoa.com/2016/01/05/bealls-list-of-predatory-publishers-2016/ (accessed on 7 Feb 2017). [Google Scholar] |

| 10. | Chawla DM. Mystery as controversial list of predatory publishers disappears. Science, 17 Jan 2017. doi:10.1126/ science.aal0625. Available at www.sciencemag.org/news/2017/01/mystery-controversial-list-predatory-publishers-disappears (accessed on 7 Feb 2017). [Google Scholar] |

| 11. | Code of Conduct. COPE. Available at http://publicationethics.org/resources/code-conduct (accessed on 7 Feb 2017). [Google Scholar] |

| 12. | COPE, DOAJ, OASPA, WAME. Principles of transparency and best practice in scholarly publishing. 22 June 2015. Available at www.wame.org/about/principles-of-transparency-and-best-practice (accessed on 11 Feb 2017). [Google Scholar] |

| 13. | Crawford W. ‘Trust me’: The other problem with 87% of Beall's lists. Walt at Random (blog). 29 Jan 2016. Available at http://walt.lishost.org/2016/01/trust-me-the-other-problem-with-87-of-bealls-lists/ (accessed on 11 Feb 2017). [Google Scholar] |

| 14. | Brazilian Forum of Public Health Journals Editors and the Associação Brasileira de Saúde Coletiva (Abrasco, Brazilian Public Health Association). Motion to repudiate Mr Jeffrey Beall's classist attack on SciELO. SciELO in Perspective. 2015. Available at http://blog.scielo.org/en/2015/08/02/motion-to-repudiate-mr-jeffrey-bealls-classist-attack-on-scielo/ (accessed 11 Feb 2017). [Google Scholar] |

| 15. | Coyle K. Predatory publishers,peer to peer review. Library J, 4 April 2013. Available at http://lj.libraryjournal.com/ 2013/04/opinion/peer-to-peer-review/predatory-publishers-peer-to-peer-review/#_ (accessed on 7 Feb 2017). [Google Scholar] |

| 16. | Emery J. Heard on the net: It's a small world after all: Traveling beyond the viewpoint of American exceptionalism to the rise of the author. Charleston Advisor 2013;15:67–8. doi: 10.5260/chara.15.2.67. Available at http:// archives.pdx.edu/ds/psu/10134 (accessed on 7 Feb 2017). [Google Scholar] |

| 17. | Crawford W. ‘Ethics and access 1: The sad case of Jeffrey Beall,’ Cites and Insights 2014;14:1–14. Available at http://citesandinsights.info/civ14i4.pdf (accessed on14 Feb 2017). [Google Scholar] |

| 18. | Directory of Open Access Journals. Available at https://doaj.org/faq#whatis. (accessed on 11 Feb 2017). [Google Scholar] |

| 19. | Think Check Submit. Available at http://thinkchecksubmit.org/ (accessed on 11 Feb 2017). [Google Scholar] |

| 20. | Aggarwal R, Gogtay N, Kumar R, Sahni P; Indian Association of Medical Journal Editors. The revised guidelines of the Medical Council of India for academic promotions: Need for a rethink. Natl Med J India. 2016;29:1– 5. Available at http://www.nmji.in/showBackIssue.asp?issn=0970-258X;year=2016;volume=29;issue=1;month=January-February (accessed on 14 Feb 2017). [Google Scholar] |

| 21. | Memon AR. ResearchGate is no longer reliable: Leniency towards ghost journals may decrease its impact on the scientific community. J Pakistan Med Assoc 2016;66:1643– 7. Available at http://www.jpma.org.pk/full_article_text.php?article_id=8019 (accessed on 11 Feb 2017). [Google Scholar] |

Fulltext Views

3,590

PDF downloads

1,426