Translate this page into:

Indian healthcare at crossroads (Part 1): Deteriorating doctor–patient relationship

Corresponding Author:

Anil Chandra Anand

Department of Gastroenterology, Indraprastha Apollo Hospital, Sarita Vihar, New Delhi 110076

India

anilcanand@gmail.com

| How to cite this article: Anand AC. Indian healthcare at crossroads (Part 1): Deteriorating doctor–patient relationship. Natl Med J India 2019;32:41-45 |

′Something is rotten in the State of Denmark. ‘—Marcellus ‘Then we should let God take care of it ‘—Reply by Horacio in a scene from Hamlet by Shakespeare[1]

Three friends, an Indian, a Britisher and a Saudi Arabian were having dinner. The Britisher was curious, ‘Why do Indians use this tagline—‘Incredible India’? The Indian said, ‘Let me explain. Tell me what would you do in your country if a newly constructed overbridge collapses, crushing 20 people under it? ' The Britisher was amused, ‘Well, the engineer and other officials responsible for the mishap would be j ailed for the rest of their lives, for sure. ' The Saudi Arabian also chipped in, ‘The irresponsible officials would be shot three times in the head and hanged in public if I had my way.' The Indian smiled and said, ‘We have a very different approach; we will take the injured people to the hospital and beat up the doctor if anyone dies! ' The Britisher and Saudi said in a chorus, ‘Oh, incredible! ' Jokes such as this are commonly told among doctors and reflect how the medical profession feels today.

The Doctor-Patient Relationship

Till a few decades ago, medicine was one of the most sought-after vocations, and doctors were highly respected members of Indian society. A family doctor’s advice was sought not only during illness but also on issues unrelated to health. Within one generation, the status of doctors in our society has been eroded to an abysmal low. Surprisingly, this has happened during a period marked by tremendous advances in the capability of modern medicine to treat disease. The respect shown to doctors by their patients and their families is now a thing of the past and has been replaced by suspicion, distrust and anger. A doctor is no longer a confidant of his patients and their families. His statements are subject to multiple verifications. He is viewed as a greedy person having a nexus with pharmaceutical companies and device manufacturers, engaged in ‘cut’ practice at the cost of suffering patients.[2] In fact, doctors are writing extensively about it themselves.[3]

The current revolution in information technology, the finance sector and service industry in India have led to thousands of young people taking up white-collar, sedentary jobs with high-stress levels. Spending long hours on computers, they frequently develop symptoms of lifestyle diseases. Then, they look up ‘Dr Google’ on their desktops and try the dietary modifications, nutritional supplements and other common remedies suggested online. When they finally do decide to visit a doctor, they think they know as much as, if not more than the average primary care physician, and hence directly seek ‘super’-specialists. Once with the superspecialist, they challenge the latter’s advice if it does not match with the results of their internet search. They demand a disproportionate amount of time and extreme patience from the doctor, have heated arguments with him, and take much effort to be convinced that what they saw on the internet was just an advertisement. This ‘syndrome’ has gradually spread to afflict even other groups in our society.

On the other hand, doctors have a different take on the situation. A friend remarked that these people gladly eat samosas and vadas fried in recycled oil, relishpaani-poori made from dirty water served with dirty hands, pay without thinking for that black poisonous liquid called this or that cola, smoke, drink and chew tobacco as if there is no tomorrow; all these without thinking twice. But after the doctor has written a prescription, they will invariably ask, ‘Are you sure there will be no side-effects?'

Doctors have a tough life. They study till the age of 30-35 years. In no other profession does one begin one’s professional life so late. People often hate them to the extent of beating or killing them when the outcome of treatment for a patient is not what was desired by the family—as if the doctor decides fate. Hospitals also do not care for them. In government hospitals, which are generally understaffed, despite working 18-hours a day, doctors never seem to be doing enough because the stream of patients is endless. In private hospitals, patients see them as greedy vultures while the hospital wishes to skin them. The hospital administrator will say, ‘Doctor, you are invaluable/ indispensable,' but is ready to replace him with another doctor promptly when profits earned from him start falling.

Doctors are also very lonely. If their spouse is not a doctor, there is no one to understand their plight. The family wonders why they must spend long hours in the hospital and then open a book the minute they arrive home. Colleagues in the same specialty are actually competitors. Their school friends enjoy life and cannot understand why the doctor cannot be there for all ‘dos’. Some of the grateful patients may respect the doctor for what they did in their crisis, but then, the doctors have been paid enough for that. Patients rarely, if ever, come out in support of their doctor when the chips are down.

Every day, the media and the government issue statements as if every man or woman is happy and immortal—until a doctor decides to loot them and kill them. Taking the doctor to court is what crosses everyone’s mind when things do not go as expected. Moreover, the doctor’s grouse is, ‘Okay, we know medical negligence is a punishable crime, but why not judicial negligence? or administrative negligence? or political negligence? or police negligence? or banking negligence? Why is only a doctor accountable to society? Why not other professions?'

New Players In The Field

Several changes in the Indian medical care system, as well as society, have also affected the doctor-patient relationship. Pharmaceutical and medical device companies have become aggressive in marketing their wares. Corporate hospitals are taking over as medical care-providers in urban areas. Since healthcare affects everyone, it has attracted the attention of the government—to regulate it—and the media, which loves to use all those involved in healthcare as its favourite whipping boys.

First, the government. The politicians are interested primarily in getting votes, and, in the process, benefit the public if possible. The pundits in the corridors of power know that new technology in healthcare is expensive[4]—so expensive that even the USA cannot afford it.[5],[6],[7] The government lacks resources to provide adequate healthcare. Hence, they have joined the public in denouncing private medical services, which provide the bulk (nearly 80%) of healthcare in the country. In addition, it has instituted stricter regulations, as if doing so would by itself make the service better and cheaper.[8] Another approach has been to promote ‘AYUSH’ (Ayurveda, Yoga, Unani, Siddha and Homeopathy) as an alternative and to allow untrained people to prescribe modern medicines.[9],[10] This has diminished the importance of doctors.[11] The indigenous medicines, in the meanwhile, remain unregulated even though there is enough evidence that these too can have adverse effects.[12],[13]

After every election, doctors as well as the public have watched elected representatives being taken to resorts for safekeeping so that they may not be ‘bought’ by the rival political party.[14] Television shows suitcases full of money[15] with news anchors asking where is this money coming from and where is it going? These very elected representatives will, a few days later, lecture doctors about ethics, making the latter wonder, ‘What is the maximum retail price of a “generic” MLA? Is it lower than that of a “branded” one?'

The pharmaceutical industry has emerged as a strong player. It is fighting the government against price-control while its members fund political parties to ensure their own survival. In India, each drug is marketed by hundreds of pharmaceutical companies, each with a different brand name—the so-called ‘branded generics’. Every company needs to sell its ‘branded generic’ to make money. While the real buyers are the patients, the companies need to convince doctors to prescribe their specific brand and are willing to spend large amounts to ensure this.[16],[17],[18] No ethical considerations are mandated for companies, and so their actions are ‘no-holds barred! ' A lot has already been written about this relationship; here again, a doctor who is in cahoots with the industry often actually remains at the receiving end.

Corporate medicine in the private sector has emerged and flourished pari passu with the decline of doctors’ image in the public eye. When corporate medicine came in early 1990s, it was initially perceived as a boon, in view of its internationally (read JCI or Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations) accredited hospitals with 5-star facilities and layers of safety checks, which had been missing in the government hospitals. Further, they soon hired all the revered and legendary professors from apex government medical institutions, luring them with hefty salaries. These hospitals were thus an instant hit with those who could afford them. Not only did they offer luxurious facilities, they were also real game changers in terms of quality of care, providing excellent results. This resulted in doctors of Indian origin migrating back from the USA and the UK to work in India. These hospitals started attracting medical tourism and claimed that they were helping the Indian economy!

However, let us look at the issue a bit more closely. Law dictionary defines corporate medicine as a group of physicians who form a corporation in order to practise medicine. Corporations are financial arrangements for a common goal. Thus, corporate medicine has two dimensions—financial and clinical. How one balances the two makes all the difference. Today, corporate hospitals are mostly business ventures, which either hire doctors on salary to see patients for them or enter into agreements with doctors to see patients on profit-sharing basis.[19] Doctors have no say in corporate policies; however, they continue to have personal liability to individual patients.[19]

Corporate hospitals soon became the benchmark of medical care. Even government hospitals desperately tried to emulate their ambience and equipment, albeit with partial success. With dismal funding for health in India, the government was never serious about upgrading healthcare services in the public sector.[20],[21]·[20],[21] Over time, corporate hospitals have proliferated, converting what was once a vocation, into an ‘industry’ (the healthcare industry).

In every sector, private organizations are better, faster and more efficient than state-run monoliths. However, several principles of economics and competition do not apply to healthcare. The private initiative in this field is replete with mines, namely excessive medical intervention and iatrogenic harm. Corporate hospitals, just like the pharmaceutical industry, are more obsessed with marketing newer and costly techniques, rather than community care.[22]

Let us look at the anatomy and functioning of a corporate hospital. Doctors form only 10%-15% of the hospital’s workforce, with technicians, nurses, secretaries, managers, marketing, finance, housekeeping, security and legal services forming the rest. Not to forget hospital administrators, who often draw salaries much higher than that of an average doctor. Where does the money for the infrastructure and salaries of all these people come from? Obviously, patients! And who has the honour of taking it out of the patient’s pocket? In the patient’s eye, it is the man on the frontline—the doctor. It is not unusual for a patient to pay a hospital bill of (₹1 million), which may include only ₹10 000 as doctor’s fees. But in the patient’s mind, it is the doctor who has charged (₹1 million). Damn the greedy doctor!

Corporate philosophy is not in sync with a doctor’s moral duties. The former ' s focus is on profits and not on the community ' s needs. The management provides bonuses and incentives to those doctors who earn them larger profits. Every doctor who joins is asked to take an indemnity insurance of at least of (?5 million), preferably double that. In effect, the hospital sends the doctor a message that ' every patient is a potential plaintiff—make sure you don’t miss anything! Cover every possibility, it is safer to over- investigate and over-treat’.[23] This leads to excessive investigation and over-treatment. It is commonplace to prod doctors to conduct aggressive screening tests for diagnosing breast, lung and colorectal cancers, even though science says that such screening may not improve overall mortality.[24],[25],[26] Working for a corporate hospital thus has an inherent conflict of interest, if one has to toe the corporate line.

A few decades ago, there was a public outcry about poor medical care. Today, the balance has tipped on the other side, and the people are crying about ‘over-care’.[27] Why else would a medical profession, after writing 16.2 million prescriptions of antidepressants a year for longer than a decade, discover that these drugs are no better than placebo in a majority of cases?[28],[29] Even in the USA, there is talk of surgeries being done which may not benefit the patient.(30] Over-care is a global phenomenon; however, its implications are harsher for poorer societies.

Doctors’ Own Conduct: Conflicts Of Interest And Other Infractions

Corporate medicine is not the only evil that doctors are nurturing in their backyard. Often their own conduct is not free from blemish. Associations of medical professionals accept large corporate donations from cola companies, manufacturers of milk substitutes and pharmaceutical and vaccine companies. Such actions constitute a conflict of interest, because these can be expected to raise a reasonable suspicion that associations (as also doctors) are open to putting aside their primary interests (which is the patient’s benefit and public health) in favour of secondary interests (financial gains for the association or luxurious dinners/ vacations for themselves), given a temptation. A physician’s commitment to patient and public health is a moral duty and not a mere interest.[31] Such actions erode public’s trust in physicians.

Trust is a delicate matter, depends as much on appearances as on reality. Imagine a judge who is deciding a case involving a contract dispute between two companies. It is discovered that he owns stock worth ₹1 000 000 in one of the companies, which he had not revealed. This constitutes a conflict of interest. Its discovery would erode people ‘s trust in his neutrality. The judge cannot divert criticism by arguing, ‘But wait until I deliver my verdict—how do you know that I won’t rule against the company in which I own stock?[32]

As discussed above, ethical conduct is the doctor’s responsibility, not the hospitals. In fact, corporate hospitals even advise doctors to remain ethical. However, it is difficult to do so when the doctor works for an organization for whom financial interest is an essential prerequisite for its survival. Doctors cannot advertise—so the hospital’s huge marketing department steps in to do this. It also offers incentives (service fee! read ‘cuts’) to general practitioners for referrals. In fact, they have effectively turned many general practitioners into touts! Today, a quack, a semi-qualified general practitioner or another so-called ‘doctor’ (an unqualified practitioner) can earn more from referrals to a corporate hospital for complex surgeries/procedures, than from the fees that he can earn by treating patients. If doctors choose to work like this, they cannot complain about the public’s distrust of them and anger!

Beating up doctors has become commonplace. Often, the doctor who is beaten up may not have done anything inappropriate. He is merely paying for the sins of his class! In any case, violence can never be justified. Such behaviour instead begets erosion of doctor’s trust in patients and their family, worsening the doctor- patient relationship further, and the doctors adopting unnecessary investigations and over-care, lest they be accused of having missed something—thus perpetuating a vicious cycle.

Is The Government Fanning The Fire?

Doctors are a scarce but valuable resource for the country. It takes decades of hard work and several competitive examinations to become a doctor, and many more years to become a mature one.to two major changes in our society—both related to the government’s decisions. One, of course, was the opening up of corporate healthcare as discussed above. The second was the colleges, owned mostly by politicians. The murkiness of this issue can be gauged from the news item that the President of the associates were arrested during 2010 by the Central Bureau of Investigation while accepting a bribe (₹20 million) to grant licence to a medical college. These colleges charge hefty capitation fees for admission. If one pays (₹3 million) to enter a medical college after obtaining zero marks in National Eligibility-cum- Entrance Test (NEET),[33] and then ₹1 million per year as college fees,[34] one would look to get quick and sufficient return on this ‘investment’. However, this is impossible in government service or with ethical private practice. Hence, such doctors may consider medicine as a business.

But then, there are doctors who are devoted and work selflessly in the service of humanity. Thus, the government’s statements[35]painting the entire medical profession with the same black brush, and declaring them greedy and corrupt, does a disservice to the honest majority, demoralizing them in the process. Such public humiliation by the government and political leaders can be expected to induce some doctors to prematurely retire from clinical practice, worsening the physician availability, and the others to give in and adopt the practices that they were being accused of, albeit wrongly. If one is being called a ‘money-sucker’ anyway, why not be one and at least make money.

Violence against doctors and destruction of property in hospitals and clinics is not acceptable. And it is worse when political and community leaders participate in it or lead it. Frequent violence has the potential to lead to collapse of the healthcare system. Realizing this, legislatures of many states have passed laws prohibiting such violence, and even making it a cognizable and non-bailable offence. However, the implementation of these laws is at best patchy and hardly any case reaches the logical end— conviction. Unless the government takes a determined stand against such violence, it will not stop.

So What Can Be Done?

Mahatma Gandhi said, Health is the real wealth of a nation’. The government has so far been unable to provide adequate healthcare facilities. Nearly two-thirds of all health expenses by Indians are paid ‘out of pocket’. India has about ₹0.92 million MBB S doctors and about ₹0.75 million AYUSH doctors (making a total of ₹1.67 million doctors), with 30 000-40 000 of each being added every year.[36] This is a reasonable number for (₹1.3 billion) Indians—one doctor per 778 persons. However, 74% of all doctors cater to one- third of the population that lives in cities—because of their somewhat better paying power.[37] The remaining population remains woefully under-served. Apart from that, there is a shortage of tertiary-care specialists as well as facilities. Where these do exist, there is a hopeless filtering and referral system. And finally, running of the existing infrastructure leaves much to be desired. These problems are well known and solutions can be found, given a political will.

One way is to nationalize healthcare on the lines of the National Health Service (NHS) in the UK, the so-called Beveridge model. One can visualize two major problems with this. The government has neither the desire nor the inclination to take on this thankless job.[38]it just cannot afford it. Second, even in the UK, long waiting lists make it difficult to access specialist services; for India, with its dismal specialist-to-patient ratio, this model may be a disaster.

The second approach is to encourage socially funded health insurance or the Bismarck Model. In this context, the recent announcement of the ‘Ayushman Bharat’ scheme[39] is a welcome step. Providing basic healthcare cashless to a common man will solve a lot of the public’s woes. People need to be educated about the difference between primary and tertiary care. Today, they want to consult a superspecialist even for a common cold. This leaves superspecialists very little time to look after those who need their services the most. A robust primary care system can reduce the burden on secondary and tertiary specialists by 60%-70%.[40]

India has scores of underfunded district and other public- sector hospitals with poor facilities. The government can ask each private medical college to adopt one such nearby hospital and enhance facilities and quality of healthcare in them as a public- private partnership. Of course, this would need infusion of money into these hospitals—but it would be money well spent if the facilities to be added are well chosen. The proposed National Commission for Human Resources for Health is expected to decide on the reforms necessary in this direction, but its final form and mandate are yet to be finalized. This needs to be expedited.

Regulation of corporate and other private hospitals through The Clinical Establishments (Registration and Regulation) Act, 2010, enacted by the Central Government and similar acts by the state governments is yet another step. However, the regulatory processes in these acts need to be well thought of and have to be reasonable. For instance, there are reports that the government plans to require any private doctor to obtain an approval from a government hospital before any caesarean operation.[41] Such regulation is clearly impractical and may harm patients through delay in emergency cases.

Price control on essential drugs and devices is a welcome step. The industry’s argument that the development of new drugs and technology is expensive is valid. However, the price of innovation needs to be balanced against the public good. The government needs to regulate profits of the pharmaceutical industry, at least where the cost of innovation has already been recouped, and of corporate hospitals with due diligence. However, there is a limit to it. Some authorities believe that Drug Price Control Orders may make some newer drugs and devices disappear from the Indian market.

Forcing private doctors to provide tertiary care at prices of the Central Government Health Scheme may lead to reducing the standard of medical care in private hospitals to that available in government hospitals. There is talk of standardizing the doctor’s fee. Some government department allows only ₹51 as reimbursement of specialist consultation fee to their employees. This may be too low. Doctors find government’s attempt to reduce their fees offensive and feel their expertise is not valued. Can the government regulate the fees of lawyers too, who charge heavily by the hour? Some parity across professions is needed if we wish future generations of students to join medicine.

Furthermore, announcements such as ‘all doctors are corrupt’ have to stop. Such actions sound like the pot calling the kettle black! Aren’t several politicians corrupt too? But possibly not all. Such corrupt people—whether doctors or others—should be dealt with through legal action, while sparing others from a bad name.

Another crucial aspect that needs attention is education of our masses about health and healthcare and dispelling myths and superstitions about health issues. Increased awareness about common health problems and their simple remedies would reduce the load on healthcare facilities. Personal health insurance is not very popular. People may spend crores of rupees on a marriage, and several thousand rupees on a dinner—but would not invest a similar amount on health insurance. This attitude needs to be changed through public education. These, along with an increased availability of health infrastructure and workforce, and improving access to affordability of healthcare services are the cornerstones to improving our healthcare system.

Another useful step would be the setting up of an organization akin to the UK’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE; www.nice.org.uk) for producing evidence-based guidance and advice for health, public health and social care practitioners, and developing quality standards and performance metrics for healthcare services. This would help reduce unnecessary investigations and treatments of dubious value.

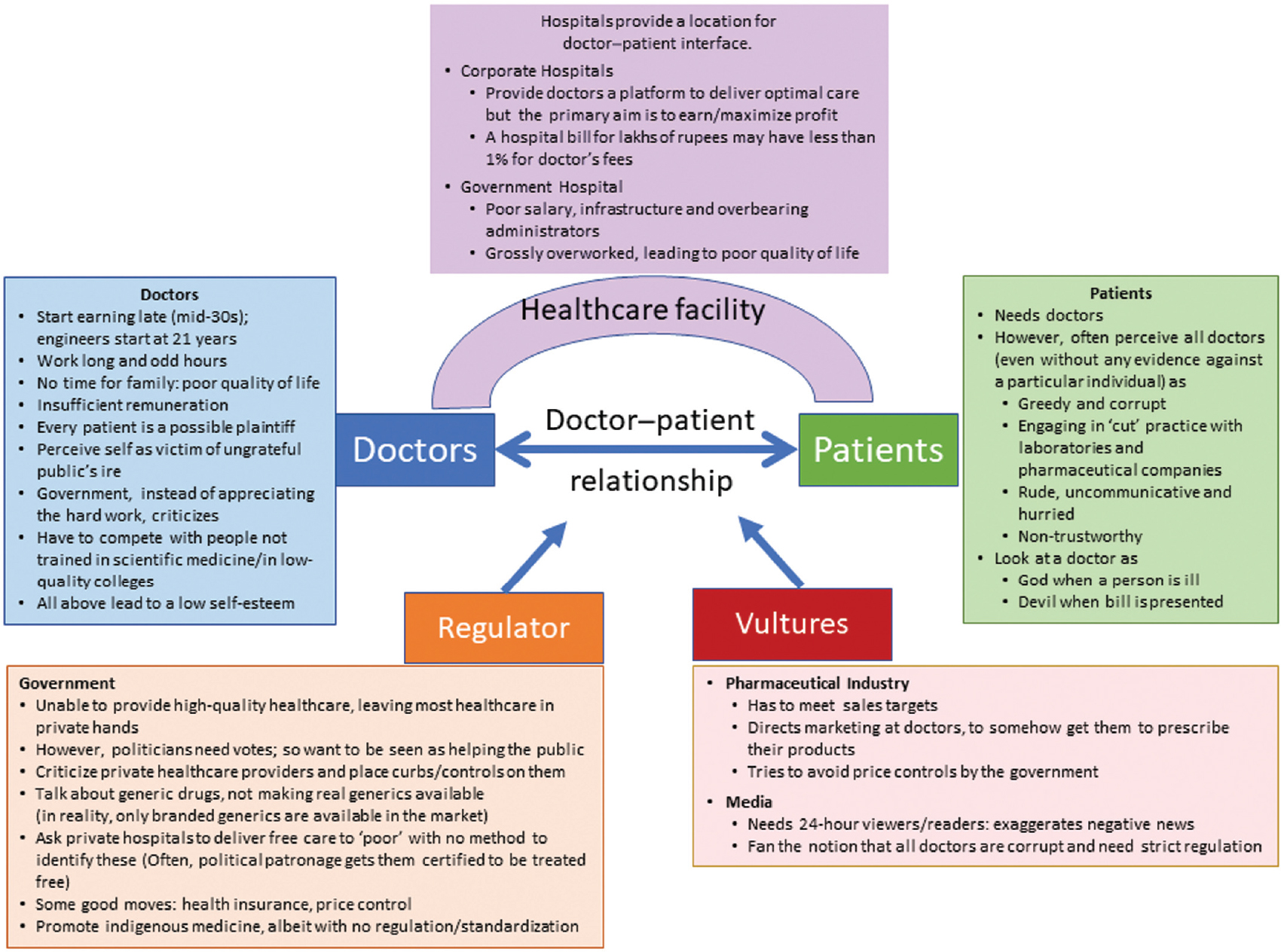

Of course, all the players in the healthcare space [Figure - 1] will need to be on the same page and to work in consultation with each other, if we are to achieve the desired result.

|

| Figure 1: Healthcare primarily involves interaction between two parties�doctors and patients (doctor–patient relationship). This relationship occurs in the context of a healthcare facility�either government-owned, doctor-owned or a corporate hospital. The relationship is currently being influenced/distorted by two types of actors: the government (regulatory activities) and societal factors which are trying to take advantage of the relationship (pharmaceutical industry and device manufacturers, and media), and hence have been referred to here as vultures |

‘Once there was a vocation called medicine that provided personalized medical care to patients. It has now evolved into healthcare industry, which controls what doctors can do. May be, the same controllers will also fund patients ' needs as the insurer and decide whether or not he will receive any care at all. It is already happening in some part of the world. '

Conflicts of interest. None declared

| 1. | Ramachandran N. What ails India’s public healthcare? Available at www.livemint.com/ Opinion/6S9Hvo31dR3aA 8h7snIWKL/What-ails-Indias-public-healthcare. html (accessed on 15 Dec 2018). [Google Scholar] |

| 2. | Berger D. Corruption ruins the doctor-patient relationship in India. BMJ 2014;348:g3169. [Google Scholar] |

| 3. | Nundy S, Desiraju K, Nagral S (eds). Healers or predators? Healthcare corruption in India. India: Oxford University Press; 2018:1-692. [Google Scholar] |

| 4. | Anand LC. New medical technology and cost effectiveness. Med J Armed Forces India 1996;52:181-3. [Google Scholar] |

| 5. | Chin M. 1 in 4 Americans refuse medical care because they can’t afford it. Available at www.nypost.com/2017/06/07/1-in-4-americans-refuse-medical-care-because- they-cant-afford-it/ (accessed on 15 Dec 2018). [Google Scholar] |

| 6. | Garson A Jr. Half of America skimps to pay for health care. The only fix is to cut waste. Available at www.usatoday.com/story/opinion/2017/10/23/cut-health-costs- put-doctors-on-salaries-arthur-tim-garson-jr-column/777179001/(accessed on 15 Dec 2018). [Google Scholar] |

| 7. | Fox M. Over 40 million in U.S. can’t afford health care: Report. Available at www.reuters.com/article/us-usa/over-40-million-in-u-s-cant-afford-health-care- report-idUSN0343703420071203?sp=true (accessed on 15 Dec 2018). [Google Scholar] |

| 8. | An unhealthy statement. Privatisation of healthcare, not just doctors, is to blame for corruption in the sector. Available at www.indianexpress.com/article/opinion/ columns/an-unhealthy-statement-narendra-modi-london-indian-doc?tors-5160669/ (accessed on 15 Dec 2018). [Google Scholar] |

| 9. | Bhuyan A. As of Now the Standards for Licensing Proprietary AYUSH Drugs Are Pretty Lax’. Available at www.thewire.in/featured/ayush-ministry-interview-ajit- sharan (accessed on 15 Dec 2018). [Google Scholar] |

| 10. | Budget allocation of AYUSH ministry hiked by 8%. Available at www.livemint.com/ Politics/tr8SA0OgI7ibU8mPFLOs4J/Budget-allocation-of-AYUSH-ministry-hiked- by-8.html (accessed on 15 Dec 2018). [Google Scholar] |

| 11. | Bill introduced in Lok Sabha seeks to allow ayurveda, homeopathy doctors to practice allopathy Available at www.thewire.in/health/bill-introduced-in-lok-sabha- allowing-ayurveda-homeopathy-doctors-to-practice-allopathy (accessed on 15 Dec 2018). [Google Scholar] |

| 12. | Ekor M. The growing use of herbal medicines: Issues relating to adverse reactions and challenges in monitoring safety. Front Pharmacol 2014;4:177. [Google Scholar] |

| 13. | Gorski D.Death by “alternative” medicine: Who’s to blame? Available at www.science basedmedicine.org/death-by-alternative-medicine-whos-to-blame/ (accessed on 15 Dec 2018). [Google Scholar] |

| 14. | BJP packs off MLAs to resort. Available at www.thehindu.com/todays-paper/tp- national/tp-karnataka/BJP-packs-off-MLAs-to-resort/article15772804. ece (accessed on 15 Dec 2018). [Google Scholar] |

| 15. | Deshpande R. Cash-on-table a first in Lok Sabha history. Available at www. timesofindia. indiatimes. com/india/Cash-on-table-a-fìrst-in-Lok-Sabha- history/articleshow/3266377.cms (accessed on 15 Dec 2018). [Google Scholar] |

| 16. | Anand AC. Professional conferences, unprofessional conduct. Med J Armed Forces India 2011;67:2-6. [Google Scholar] |

| 17. | Anand AC. The pharmaceutical industry: Our ‘silent’ partner in the practice of medicine. Natl Med J India 2000;13:319-21. [Google Scholar] |

| 18. | Anand AC. Using generic drugs in India: Some thoughts. Natl Med J India 2017;30:287-9. [Google Scholar] |

| 19. | Anand AC. A primer of private practice in India. Natl Med J India 2008;21:35-9. [Google Scholar] |

| 20. | India’s healthcare in dismal condition: Report. Available at www.business- standard.com/article/news-ians/india-s-healthcare-in-dismal-condition-report- 114092401264_1.html (accessed on 15 Dec 2018). [Google Scholar] |

| 21. | Jain D. Budget 2018: India’s health sector needs more funds and better management Available at www.livemint.com/Politics/drnszDrkbt418WpuQEHfZI/Budget-2018- Indias-health-sector-needs-more-funds-and-bett.html (accessed on 15 Dec 2018). [Google Scholar] |

| 22. | Spence D. Medicine’s leveson. BMJ2012;344:e1671. [Google Scholar] |

| 23. | Vaughan D. The dark side of organisations: Mistakes, misconduct and disaster.Ann Rev Sociol 1999;25:271-305. [Google Scholar] |

| 24. | Spence D. Greed isn’t good. BMJ 2011;342:d524. [Google Scholar] |

| 25. | Woloshin S, Schwartz LM. How a charity oversells mammography. BMJ 2012;345:e5132. [Google Scholar] |

| 26. | Mayor S. Expert group advises separating risk and benefit information from cancer screening invitations. BMJ 2012;345:e5322. [Google Scholar] |

| 27. | Harikatha R. Defensive medicine as a bane to healthcare (Winning essay one). Asian Student Med J. Available at www.asmj.netFullMiscarticle. aspx?id=8 (accessed on 15 Dec 2018). [Google Scholar] |

| 28. | Hastings G. Why corporate power is a public health priority. BMJ 2012;345:e5124. [Google Scholar] |

| 29. | Spence D. Bitter sweets. BMJ 2008;336:562. [Google Scholar] |

| 30. | Krumholz HM. Cardiac procedures, outcomes, and accountability. N Engl J Med 1997;336:1522-3. [Google Scholar] |

| 31. | Erde EL. Conflicts of interest in medicine: A philosophical and ethical morphology. In: Speece RG, Shimm DS, Buchanan AE (eds). Conflicts of Interest in Clinical Practice and Research. New York:Oxford University Press; 1996:12-41. [Google Scholar] |

| 32. | Schafer A. Biomedical conflicts of interest: A defence of the sequestration thesis- learning from the cases of Nancy Olivieri and David Healy. J Med Ethics 2004;30: 8-24. [Google Scholar] |

| 33. | NEET: Zero marks in physics, chemistry could still get you a MBBS seat Available at www. indiatoday. in/education-today/news/story/neet-zero-marks-in-physics- chemistry-could-still-get-you-a-mbbs-seat-1287180-2018-07-16 (accessed on 15 Dec 2018). [Google Scholar] |

| 34. | Nagaraj an R. High MBB S fees leaving many doctors in debt trap. The Times of India; 2018:1. Ava il ab le at www.epaper. timesgroup. com/O live/ODN/TimesOf ndia/# (accessed on 15 Dec 2018). [Google Scholar] |

| 35. | Khan SA. An unhealthy statement. Privatisation of healthcare, not just doctors, is to blame for corruption in the sector. Available at www.indianexpress.com/article/ opinion/columns/an-unhealthy-statement-narendra-modi-london-indian-doctors- 5160669/ (accessed on 15 Dec 2018). [Google Scholar] |

| 36. | Damini G. The problems of healthcare system in India and how it can be overcome. Available at www.moneylife.in/article/the-problems-of-healthcare-system-in-india- and-how-it-can-be-overcome/35105.html (accessed on 15 Dec 2018). [Google Scholar] |

| 37. | World Health Day 2019: Challenges, opportunities in India’s $81b healthcare industry. Available at www.firstpost.com/india/indias-healthcare-sector-a-look-at- the-challenges-and-opportunities-faced-by-81-3-billion-industry-3544745.html (accessed on 15 Dec 2018). [Google Scholar] |

| 38. | Health Care Systems—Four Basic Models. Available at www.pnhp.org/ single_payer_resources/health_care_systems_four_basic_models.php (accessed on 15 Dec 2018). [Google Scholar] |

| 39. | Ayushman Bharat—National Health Protection Mission. Available at www.india. gov.in/spotlight/ayushman-bharat-national-health-protection-mission (accessed on 15 Dec 2018). [Google Scholar] |

| 40. | Gupta A.Ayushman Bharat: India’s: miracle pill for all has a bitter coating. Available at www.prime.economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/65030829/pharma-and- healthcare/ayushman-bharat-indias-miracle-pill-for-all-has-a-bitter-coating (accessed on 24 Jul 2018). [Google Scholar] |

| 41. | Private hospitals will need government nod for C-section. Available at www. dnaindia. com/health/report-private-hospitals-will-need-govt-nod-for-c- section-2619455 (accessed on 15 Dec 2018). [Google Scholar] |

Fulltext Views

2,235

PDF downloads

455