Translate this page into:

India’s role in the odyssey of medical training in South Africa

Correspondence to BHUGWAN SINGH; SinghB@ukzn.ac.za

[To cite: Singh B, Singh JP, Ebrahim S, Naidoo NM. India’s role in the odyssey of medical training in South Africa. Natl Med J India 2024;37: 219–21. NMJI_1264_2023.]

Abstract

Apartheid had a devastating impact on medical education in South Africa. Until the development of the University of Natal Medical School in 1951, there were minimal opportunities for blacks (collectively Africans, Indians and so-called coloureds) to undertake undergraduate and postgraduate medical training in South Africa. At the height of apartheid (1968–1977), whites who had constituted 17% of the population, accounted for up to 87% of all medical graduates. The African majority, constituting 70% of the population had less than 5% of all medical graduates in South Africa. The global isolation of South Africa from the late 1940s further impacted negatively on the medical training for blacks in South Africa.

During apartheid, the Government of India provided full scholarships to the marginalized in South Africa to study medicine in India. This initiative, coming at a time when India was grappling with its post-colonial challenges, was a remarkable yet seldom appreciated gesture.

INTRODUCTION

The long-standing association between South Africa and India is rooted in the imperialist designs of Britain, both countries being constituents of the British empire. Central to the India–South Africa nexus was the recruitment of Indians from British controlled India between 1860 and 1911, as part of the indentureship practice that saw Indians also transported to the Caribbean region, Mauritius, Fiji and Surinam. Presently, Indians constitute 2.6% (1.6 million) of the South African population of 59.6 million.1

IMPACT OF APARTHEID2–4

In 1948, with the enactment of apartheid laws, racial discrimination was institutionalized. Race laws touched every aspect of life, including the territorial separation of the different black races (African, Indian and so-called coloured) and the denial to open access to education, free movement in the country, economic advancement with the sanctioning of ‘white-only’ jobs and privileges—all enforced by a brutal state machinery. The subtext was to control and dehumanize the collective black majority (mainly Africans [82.7% of the population], Indians and so-called coloureds) so that the white minority (17.3% of the population) could have exclusive control over political power, the economy, education and human development.

IMPACT OF APARTHEID ON MEDICAL TRAINING4,5

The impact of apartheid on medical training for blacks, as on every aspect of their human development, was devastating. Even before the apartheid legislation, poverty was omnipresent for the indentured Indian. There was a lack of formal education with secondary education available only from the 1930s. Those Indians who travelled (almost exclusively from Gujarat and the erstwhile Bombay Presidency) to South Africa outside the indentureship programme as merchants and traders escaped these vicissitudes, thus predisposing to a class divide. The latter of the wider Indian community were sufficiently resourced to access the meagre education opportunities available as well as sending their children abroad for formal education, including pursuit of medical studies.

Anti-Indian racism was exemplified by pronouncements of D.F. Malan, leader of the National Party and Prime Minister of South Africa between 1948 and 1954, who referred to Indians as an ‘alien element in South African society’, are germane, as were the constant threat to repatriate the Indian population that had toiled to develop the country since their arrival in 1860.6,7

Medical training challenges8,9

The narratives on the challenges faced by the pioneering black doctor suffer from a lack of documentation, sometimes biased writing with dependency on anecdotes occasionally with embellished views. The lack of proficiency in English, an appropriate education and adequate finances were major stumbling blocks. Missionary support and sponsorship for potential African medical students played an important role in this respect as was evident in their support of the earliest black medical graduates in South Africa, William Anderson Soga in 1883 and John Mavuma Nembula in 1887.

Wealthy Indians could pursue medical studies abroad. Until the 1920s, most undertook studies in Scotland and thereafter, up to the 1970s, in Ireland. It is not widely recognized that many undertook medical training in India from the 1920s to the 1970s. However, for the majority, access to basic education, let alone tertiary education, remained a challenge.

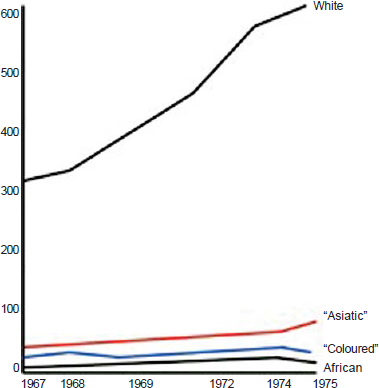

The disparities in the training of medical doctors during apartheid in South Africa are shown in Table I and Fig. 1.5

| Population | Range of annual % | Mean annual % | Mean % of total population |

|---|---|---|---|

| White | 84.3–86.7 | 85.4 | 17.3 |

| ‘Asian’ | 7.9–9.3 | 8.4 | 2.9 |

| Coloured | 1.1–4.8 | 3.4 | 9.4 |

| Black (African) | 1.3–4.8 | 3.0 | 70.4 |

- Number of graduates in each racial group, 1967–19755

During the period 1968–1977, Africans who constituted over 70% of the population had 1.3%–4.8% of medical graduates; whites constituting 17.3% of the population had 84.3%–86.7% of medical graduates. The ‘Asiatic’ group included those of Indian, Chinese and Malay origin, constituted 2.9% of the population and had 7.9%–9.3% of medical graduates.

Medical training in South Africa for blacks10

The existent medical schools in South Africa (the University of Witwatersrand and the University of Cape Town established during the late second decade of the 20th century), proscribed the under- and postgraduate medical training of blacks (collectively African, Indian and so-called coloured); it was not that no candidates were available for medical training. The blacks who left the country to pursue further studies were from the wealthy class and those sponsored by missionary agencies.

Training of black doctors in South Africa began from the early 1940s. The Universities of Cape Town and Witwatersrand began admitting blacks in 1942 and 1943, respectively. Admission to white medical schools by black students was restricted to a small number of permit holders sanctioned by the government.

After much deliberations, the white government approved the development of the University of Natal (UN) Medical school in Durban (which then had the largest settlements of Indians outside India) for the training of black medical students. The UN Medical school, which in the coming decades attained legendary status as an institution of remarkable standards and progressive political activism, admitted its first students in 1951, with 12 students graduating in 1957. Three of the 6 Indian graduates were women, among whom was the pathologist Dr Soromini Kallichurum (Fig. 2), who later became the first woman professor and head of department. Dr Kallichurum was also the first woman and Black Dean of a Medical School in South Africa, later becoming the first president of the Health Professional Council of South Africa (1998–2002), of the liberated South Africa.

- Dr Soromini Kallichurum

Postgraduate training for blacks4

For those who studied abroad, there was no scope for postgraduate training on their return to South Africa. Degrees obtained abroad were often not recognized. There was little scope for public employment. Race and language constrained the pursuit of any academic ambitions.

Beyond the all-pervasive and legislated racism, tentacles of apartheid extended to just about every aspect of the black doctor’s work experience and professional development.

For the black hospital doctors, there were separate (and inferior) amenities, discriminatory leave periods, housing subsidies and pension schemes as well as differential salaries: Indians and so-called coloured earned 70%–80% and Africans 65%–70% of the salary of white colleagues. For the white establishment, there was anxiety about black doctors issuing instructions to white nurses and/or white junior doctors, thereby subverting the established racial hierarchy of apartheid. This resulted in black practitioners being pressurized to hand over patients to white colleagues in smaller suburban hospitals. White nurses refused to take orders and instructions from black doctors who were also prevented from prescribing/dispensing medicines without permission.

Internship for black doctors was not readily available, with positions at hospitals that treated only black patients such as King Edward VIII Hospital, McCord Zulu Hospital, Baragwanath Hospital and Kimberley Hospital or abroad, in Cairo or Dublin. In most cases, this gave a narrower clinical experience that focused only on black patients and their common diseases so that a specialist career was difficult to develop. These restrictions were not applied to white doctors.

With little scope for postgraduate training prompted by the absence of an enabling environment in the workplace, the absence of role models, separate and inferior amenities, it was inevitable that many left the country to pursue their academic ambitions— an enforced brain drain of exceptionally talented doctors.

For white doctors, there was access to extra tutorials and grooming processes that included postgraduate training abroad and entry to a specialist track. White doctors from abroad (largely the UK and Europe) were attracted to the material benefits reserved for whites in South Africa, as well as the opportunities to gain technical experience and fast track their careers.

INDIA’S CONTRIBUTION TO MEDICAL TRAINING OF BLACK SOUTH AFRICANS

India’s anti-apartheid stance was long-standing, predating India’s own liberation from the British and the creation of the United Nations. This position went beyond the discrimination meted out to Indians in South Africa.11

India’s first President, Dr Rajendra Prasad, in his address to the Indian Parliament in May 1952, stated:

The question is no longer merely one of the Indians in South Africa, it has already assumed a greater and wider significance. It is a question of racial domination and racial intolerance. It is a question of the future of the African more than of Indians in South Africa.12

India doggedly raised the South African issue at appropriate forums and at the United Nations. Beginning in 1946, India was the first country to impose political and economic sanctions against South Africa and played an exemplary role against racialism and colonialism single-handedly at a time when there was no African representation at the United Nations and other international forums.12

India matched its call for sanctions against South Africa and its isolation from the comity of nations by providing, in addition to material support to the South African liberation movement, full scholarships to study medicine in India. It is beyond the scope of this submission to detail these initiatives which spanned form 1947 to 1990, during a period when India was deeply affected by many domestic challenges of its own. This initiative was a humanitarian response reflective of an ancient civilizational ethos; admirably, it was not driven by a quid pro quo agenda. This is a debt, largely unknown, that South Africa owes to India.

In essence, for those denied the opportunity to study medicine in South Africa or those who could not afford to study in the UK (or elsewhere abroad), India provided the opportunity to pursue medical studies to those with the requisite academic criteria. Until the mid-1970s, the selection and placement was administered by the Indian Council for Cultural Relations; thereafter, this process was overseen by the African National Congress, then the South African liberatory movement recognized by the Government of India as the legitimate representative of South Africans. Grant Medical College, Topiwala National Medical College, Seth Gordhandas Sunderdas Medical College (Mumbai), Prince of Wales Medical College (Patna), King George Medical College (Lucknow)—among several other medical colleges in India—are fondly remembered for providing the opportunity to South Africans to study medicine. Dr Shunmugan Govender and Dr Hoosen Coovadia trained at Grant Medical College and Dr K.S. Naidoo at the Prince of Wales Medical College (infra vide).

Several beneficiaries of India’s largesse have made great contributions to medicine in South Africa as heads of departments (Professors K.S. Naidoo and Shunmugan Govender in Orthopaedics and Professor H. Coovadia in Paediatrics), as heads of clinical units, specialists, administrators and general practitioners. Professor Coovadia is also recognized internationally as an HIV/AIDS researcher and for his leadership in the struggle against apartheid.

The great difficulties that Africans encountered in procuring travel documents and funding for the travel to India resulted in fewer Africans utilizing the scholarships awarded by the Government of India. The refusal to issue passports to African applicants confirms the insensitivities and vindictiveness of the apartheid government.

Notwithstanding the progress made in the training of black specialists, appropriate demographic representations in the academic departments across the country remains a challenge, a legacy of the disastrous effects of the social engineering central to apartheid.

The odyssey of black doctors in South Africa is emblematic of the poet Tennyson’s Ulysses:

‘….. to strive, to seek, to find, and not to yield’.

Today, black specialists play a pivotal role in undergraduate and postgraduate training and service delivery. A burgeoning research ethos is noted, as reflected by the number of PhDs being pursued and completed.

The enormous sacrifices made by our pioneers and the support provided by sensitive and progressive countries, especially India, are unrepayable debts.

- Indian indentured labour in Natal, 1890–1911. Indian Eco Soc History Rev. 1977;141:519-47.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- History of apartheid education and the problems of reconstruction in South Africa. Sociol Study. 2013;3:1-12.

- [Google Scholar]

- Black doctors and discrimination under South Africa’s apartheid regime. Med Hist. 2013;57:269-90.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Apartheid and medical education: The training of black doctors in South Africa. J Natl Med Assoc. 1980;72:395-410.

- [Google Scholar]

- Reducing the Indian population to a ‘manageable compass’: A study of the South African assisted emigration scheme of 1927. Natalia. 1985;15:36-56.

- [Google Scholar]

- The “coolie curse”: The evolution of white colonial attitudes towards the Indian question 1860–1900. Historia. 2012;57:31-67.

- [Google Scholar]

- India-South Africa––a collection of papers by E. S. Reddy. The University of Durban-Westville, Durban. Occasional Papers Series. 1991;1:30.

- [Google Scholar]

- Khan Muslim M. India–South Africa unique relations. Indian J Political Sci. 2010;71:613-34.

- [Google Scholar]

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Apartheid: The United Nations and the international community: A collection of speeches and papers University of Michigan: Vikas Publishing House; 1986.

- [Google Scholar]