Translate this page into:

Knowledge, attitude and behaviour of the general population towards organ donation: An Indian perspective

2 Department of Psychiatry, National Institute of Mental Health and Neuro Sciences, Bengaluru, 560029, Karnataka, India

Corresponding Author:

Poreddi Vijayalakshmi

Department of Nursing, National Institute of Mental Health and Neuro Sciences, Bengaluru, 560029, Karnataka

India

pvijayalakshmireddy@gmail.com

| How to cite this article: Vijayalakshmi P, Sunitha T S, Gandhi S, Thimmaiah R, Math SB. Knowledge, attitude and behaviour of the general population towards organ donation: An Indian perspective . Natl Med J India 2016;29:257-261 |

Abstract

Background. The rate of organ donation in India is low and research on organ donation among the general population is limited. We assessed the knowledge, attitude and willingness to donate organs among the general population.Methods. We carried out a cross-sectional descriptive study among 193 randomly selected relatives of patients (not of those seeking organ donation) attending the outpatient department at a tertiary care centre. We used a structured questionnaire to collect data through face-to-face interviews.

Results. We found that 52.8% of the participants had adequate knowledge and 67% had a positive attitude towards organ donation. While 181 (93.8%) participants were aware of and 147 (76.2%) supported organ donation, only 120 (62.2%) were willing to donate organs after death. Further, there were significant associations between age, gender, education, economic status and background of the participants with their intention to donate organs.

Conclusion. Our study advocates for public education programmes to increase awareness among the general population about the legislation related to organ donation.

Introduction

Organ donation is defined as an act of giving one or more organs, without compensation, for transplantation to another person. [1] Although, organ donation is a personal issue, the process has medical, legal, ethical, organizational and social implications. [2], [3] Technological advances in the past few decades have enhanced the feasibility of organ transplantation, which has pushed the demand for organs. Consequently, shortage of organs has become a global concern. [4]

In India, the Transplantation of Human Organs Act (THOA) was enacted in 1994. [5] Yet the rate of organ donation in India is poor (0.34 per 100 000 population) compared to developed countries. [6] In addition, organ donation following brainstem death is infrequent in India. THOA (1994) defines brainstem death as ′the stage at which all functions of the brainstem have permanently and irreversibly ceased′. [7] Attitudes are generally influenced by social and cultural factors. [8] Knowledge, attitude and behaviour are the key factors that influence rates of organ donation. [9],[10],[11] Culture and religion have also been documented to affect the decision-making process of organ donation. [8] Hence, it is crucial to assess the knowledge and attitudes of the general population towards organ donation. In India, published evidence on organ donation is mainly from studies among healthcare workers, [12] patients [13] and college students. [14] However, some research is available about organ donation among the general [15] and rural populations. [16] We assessed the knowledge, attitudes and willingness to donate organs among the general population.

Methods

We carried out this cross-sectional descriptive survey among relatives of patients attending the outpatient department (OPD) at a tertiary care centre in Bengaluru. The study sample was selected by a lottery method based on the OPD registry. We included all individuals ≥18 years of age and those who were willing to participate. We excluded people with cognitive impairment and relatives of patients who were in need of organs for transplantation. We asked 275 people to participate in our study; of them, 82 (30%) declined due to lack of time and interest. Hence, our final sample had 193 people.

Data collection instrument

The questionnaire was in four parts. The first part consisted of items about sociodemographic details of the participants such as age, gender, education, religion, economic status, marital status and place of residence. In addition, five questions related to participants′ awareness about organ donation, brain death, legislation, opinion on promotion of organ donation and sources of information about organ donation.

The second part intended to measure the knowledge level of participants about organ donation. [17] This had two components. One was a list of 11 items with true/false response options in five subscales, namely general donation-related statistics (2 items), knowledge of the donation process (3 items), knowledge of what signing a donor card means (3 items), knowledge of medical suitability for donation (2 items), and knowledge of religious institutions′ approach to donation (1 item). With one mark for every correct response, the maximum score in this component was 11. The second component of this part measured experiential knowledge of people (8 items) about organ donation and organ transplantation in three domains: (i) personal knowledge of a donor or donor family member (3 items); (ii) personal knowledge of a person on a waiting list (2 items); and (iii) personal knowledge of an organ/tissue recipient (3 items).

The third part consisted of 22 items assessed on a 5-point Likert scale that ranged from ′strongly disagree′ to ′strongly agree′. These items assessed perceptions and attitudes of participants toward organ donation. [17] Points ranging from 1 to 5 were given to each response such that the more positive the response, the higher the score. The range of scores for this scale was 22 to 110.

The fourth part of the questionnaire measured participants′ willingness to donate organs. Intent to sign the card was measured on a 5-point scale developed by Skumanich and Kintsfather [18] (1: I will definitely sign the card; 2: I will probably sign the card; 3: I am unsure as to whether or not I will sign it; 4: I will probably not sign it; and 5: I will definitely not sign it). A sixth item was added to identify participants who had already signed an organ donation card. [19]

Data collection

We piloted the questionnaire among a group (n=20) of participants and we found that the study was feasible. The primary author collected the data through a face-to-face interview, in a private room at the treatment facilities where the participants were recruited. It took approximately 45-50 minutes to complete the structured questionnaire.

Ethical considerations

The ethics committee of the hospital approved the study protocol. The researchers approached the participants and briefly explained the purpose of the study. Written con-sent was obtained from the participants and they were given the freedom to quit the study at any time. Participants′ confidentiality was respected.

Data analysis

Before analysis, negatively worded items were reverse coded. Descriptive (frequency, percentage, mean and standard deviation) and inferential (chi-square test) statistics were used to interpret the data. Statistical significance was considered at p<0.05.

Results

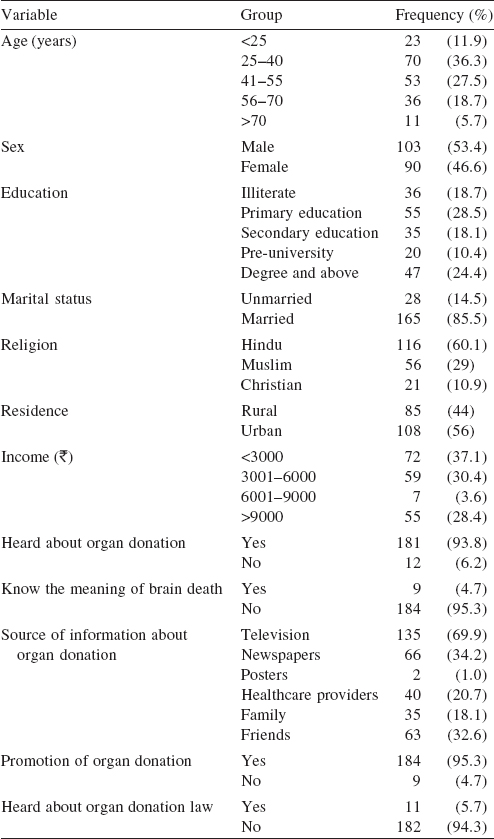

Of the 193 people interviewed, 103 (53.4%) were men. The majority of participants were between 25 and 40 years (36.3%) with a mean (SD) age of 44.1 (1.55) years ([Table - 1]). The majority were married (85.5%), Hindus (60.1%) and from an urban background (56%). While most of them (93.8%) were aware of organ donation, only 5.7% had heard about the organ donation law ([Table - 2]). With regard to organ donation statistics, the majority of people were not aware about the demand of organs for transplants (100, 51.8%) and that people on the waiting list for transplant die every day because of non-availability of organs (130, 67.4%). Participants possessed better knowledge about the process of organ donation as the majority approved that organ and tissue donation does not disfigure the body, so an open casket funeral is possible (161, 83.4%) and said that selling organs is illegal in India (168, 87%). A majority of the participants were aware that people can specify on a donor card about the organs and tissues they wanted to donate (146, 75.6%), and donors can change their mind about organ donation after signing the donor card (137, 71%). More than half the participants (101, 52.3%) agreed that religious people do not oppose organ and tissue donation. However, the mean (SD) knowledge score (5.81 [1.84] ) showed that only 52.8% of participants had adequate knowledge about organ donation. Regarding experiential knowledge, more participants were familiar with people who were on dialysis (130, 67.4%) and had a corneal transplant (69, 35.8%).

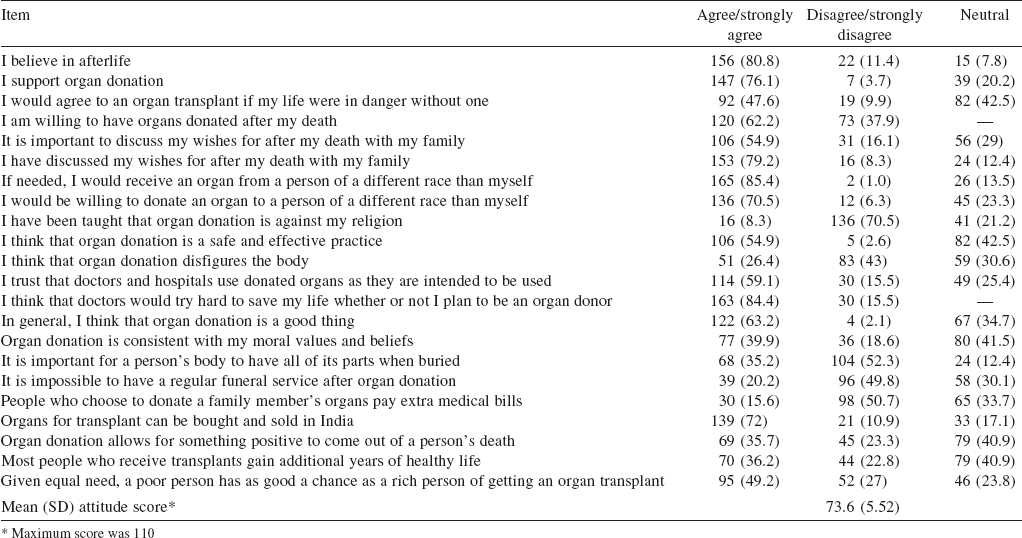

Over three-fourths of the people supported organ donation (147, 76.2%) and 120 were willing to donate organs after death (62.2%). The majority of people (106, 54.9%) recognized the importance of discussing their wishes related to organ donation with their family and disagreed that their religion taught against organ donation (136, 70.5%). The mean (SD) attitude score (73.6 [5.52]) indicated a positive attitude among the study population. Seventy-nine participants (40.1%) were willing to sign an organ donation card but only 1 among them had signed an organ donation card ([Table - 3]).

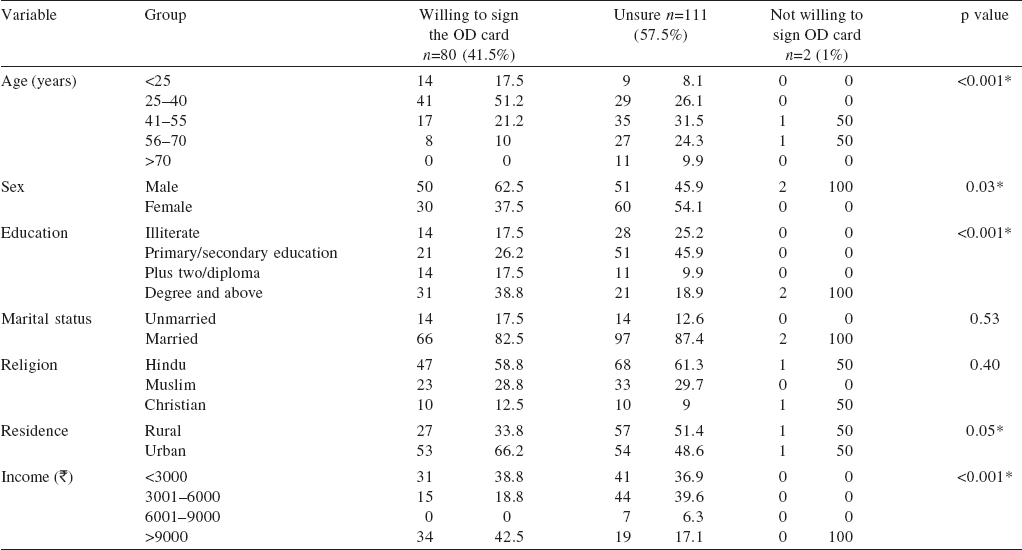

There was a significant association between sociodemographic variables and participants′ willingness to sign an organ donation card. More number of participants below 40 years (55, 68.7%) were willing to sign the organ donation card (p<0.001). While 60 (54.1%) of the women were unsure, majority (50, 62.5%) of men were in favour of signing an organ donation card (p<0.03). Participants with lower education (p<0.001), those from a lower socioeconomic status p<0.001) and rural background (p<0.05) were unsure about signing the organ donation card. A majority of participants (59, 67.8%) with poor knowledge were unsure (p<0.02) of signing an organ donation card ([Table - 4] and [Table - 5]).

Discussion

We aimed to assess knowledge and attitude of the general population towards organ donation. The results show that the majority of participants had heard about organ donation and had a positive attitude towards organ donation. However, only 1 participant had signed an organ donation card. We also explored the experiential knowledge of the participants related to organ donation and found a significant association between sociodemographic variables and willingness to sign an organ donation card.

The majority (93.8%) of participants in our study were aware of organ donation and these findings are similar to those of previous studies. [13],[14],[16] In line with previous research, [14],[ [20],[21],[22],[23] we also found that television and newspapers were the major sources of information on organ donation. Similar to previous studies, [14],[24] in the current study merely 20.7% of the participants received information through healthcare providers such as doctors and nurses. Most importantly, only 4.7% of the individuals knew about the meaning of brain death. A recent retrospective case record analysis of over 5 years revealed that of 205 patients diagnosed to be brain dead, organs were donated only in 10 (5%) cases. [25] Hence, governmental and non-governmental agencies should take an active part in creating awareness about brain death among the general population. THOA was enacted in 1995, yet only 5.7% of the participants were aware about legislation related to organ donation. These findings were comparable to the studies which showed that 13.9% and 14.1% of participants were aware of legislation related to organ donation. [14],[23],[26] Nearly all (95.3%) the participants in our study were in favour of organ donation.

In our study, 52.8% of participants had adequate knowledge about organ donation. These findings were comparable to a previous study that showed 41.5% of participants had knowledge about organ donation. [27] The majority of participants in our study opined that organ donation does not disfigure the body so an open casket funeral is possible. Interestingly, this is different from earlier studies that found maintaining body integrity after death to be the most common reason for unwillingness to donate organs. [28] Similar to developed countries, [29] there is a shortage of organs in India, and many patients die while on the waiting list due to the shortage of organs. [14] In general, after signing the organ donation card it will be given to the donor [22] and in case the donor changes their mind about donating organs, they can tear up the organ donation card. [22] The majority (71%) of participants in our study believed that they cannot change their mind once they have signed the organ donation card. Hence, these issues need to be addressed when planning public education programmes. Nearly half the sample thought that various religions oppose organ and tissue donation. These findings were similar to the documented literature which showed that religious beliefs were the major barrier for organ donation. [22],[27],[30]

Evidence in the literature indicates that personal experience about organ donation contributes to the knowledge of individuals [31] and subsequently organ donation rates. Traditionally in India, the family takes care of its members even when they are sick. Hence, the consent of the next of kin is mandatory for organ donation from a deceased donor. [12] Further, 54.9% of participants felt that after their death it is important to know their family′s wishes. In a recent study, 83% of people thought that family/spouse should have the right to make a decision for organ donation. [14] Thus, a positive attitude towards organ donation is necessary among family members. [32] Nonetheless, a majority of them in our study were enthusiastic to either donate or receive organs. [33] Earlier studies indicate that trust in the medical system positively influences peoples′ attitude towards organ donation. [34] For example, fear of premature declaration of death and improper use of organs were the key reasons that hindered organ donation. [35] However, illegal organ donation and misuse of organs are the main reasons for the low rate of organ donation in India. [5] Similar to previous studies, 72% of individuals opined that organs for transplant can be bought and sold in India and this can be a major barrier to organ donation. [15] Similar to a recent study, [23] the majority of participants in our study had a positive attitude towards organ donation. Though 93.8% of participants were aware of and supported organ donation, only 62.2% of participants were willing to sign an organ donation card. Hence, there is an urgent need to identify factors that influence such an attitude. Governmental and non-governmental agencies should clarify issues related to signing organ donation cards. In line with previous research, [37],[38], our study also showed significant associations between age, gender, education, economic status, and background of the participants with intentions to donate the organs. We found that men (62.5%) were more willing to donate their organs than women (37.5%); these findings complement the documented literature. [14],[22],[37] Similar to our study, Azkan and Yilmaz found that those who are young and with higher education had more positive attitudes towards donating organs. [30] Similarly, participants with adequate knowledge were more willing to sign the organ donation card. [31],[38]

Limitations

Our study has limitations of a cross-sectional design and a small sample that consisted of patient′s relatives. This makes it difficult to generalize the findings. Therefore, future studies should include larger samples and qualitative studies such as focus group discussions for an in-depth understanding of the issues. However, we studied a random sample with participants from various backgrounds, which is a strength of this study.

Conclusion

Our study highlights that though a majority of participants were aware of and supported organ donation, only two-thirds were willing to sign an organ donation card. The majority of participants were unaware of the legislation and the process of organ donation. Our study showed the importance of the media in creating awareness about organ donation among the general population.

We suggest that the government should also strengthen the infrastructure of hospitals to maintain potential brainstem dead donors.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the participants for their valuable contribution.

| 1. | Gruessner R. Organ donation. Available at www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/431886/organ-donation (acessed on 15 Dec 2014). [Google Scholar] |

| 2. | Edwards TM, Essman C, Thornton JD. Assessing racial and ethnic differences in medical student knowledge, attitudes and behaviors regarding organ donation. J Natl Med Assoc 2007; 99: 131-7. [Google Scholar] |

| 3. | Ghods AJ. Ethical issues and living unrelated donor kidney transplantation. Iran J Kidney Dis 2009; 3: 183-91. [Google Scholar] |

| 4. | Badrolhisam NI, Zukarnain Z. Knowledge, religious beliefs and perception towards organ donation from death row prisoners from the perspective of patients and non-patients in Malaysia: A preliminary study. Int J Humanit Soc Sci 2012; 2 (24 Special Issue):197-206. [Google Scholar] |

| 5. | Shroff S. Legal and ethical aspects of organ donation and transplantation. Indian J Urol 2009; 25: 348-55. [Google Scholar] |

| 6. | Mohan Foundation. Deceased donation statistics. Indian Transplant Newsletter 2014-15; 14 (43) . [Google Scholar] |

| 7. | The Transplantation of the Human Organs Act, 1994. Available at http://health.bih.nic.in/Rules/THOA-1994.pdf (accessed on 31 Jan 2016). [Google Scholar] |

| 8. | Chung CK, Ng CW, Li JY, Sum KC, Man AH, Chan SP, et al. Attitudes, knowledge, and actions with regard to organ donation among Hong Kong medical students. Hong Kong Med J 2008; 14: 278-85. [Google Scholar] |

| 9. | Rithalia A, McDaid C, Suekarran S, Norman G, Myers L, Sowden A. A systematic review of presumed consent systems for deceased organ donation. Health Technol Assess 2009; 13: iii, ix-xi, 1-95. [Google Scholar] |

| 10. | Rithalia A, McDaid C, Suekarran S, Myers L, Sowden A. Impact of presumed consent for organ donation on donation rates: A systematic review. BMJ 2009; 338: a3162. Available at www.bmj.com/content/338/bmj.a3162 (accessed on 14 Dec 2016). [Google Scholar] |

| 11. | Mekahli D, Liutkus A, Fargue S, Ranchin B, Cochat P. Survey of first-year medical students to assess their knowledge and attitudes toward organ transplantation and donation. Transplant Proc 2009; 41: 634-8. [Google Scholar] |

| 12. | Ahlawat R, Kumar V, Gupta AK, Sharma RK, Minz M, Jha V. Attitude and knowledge of healthcare workers in critical areas towards deceased organ donation in a public sector hospital in India. Natl Med J India 2013; 26: 322-6. [Google Scholar] |

| 13. | Mithra P, Ravindra P, Unnikrishnan B, Rekha T, Kanchan T, Kumar N, et al. Perceptions and attitudes towards organ donation among people seeking healthcare in tertiary care centers of coastal South India. Indian J Palliat Care 2013; 19: 83-7. [Google Scholar] |

| 14. | Annadurai K, Mani K, Ramasamy J. A study on knowledge, attitude and practices about organ donation among college students in Chennai, Tamil Nadu 2012. Prog Health Sci 2013; 3: 59-65. [Google Scholar] |

| 15. | Josephine G, Little Flower R, Balamurugan E. A study on public intention to donate organ: Perceived barriers and facilitators. Br J Med Pract 2013; 6: a636. [Google Scholar] |

| 16. | Manojan KK, Raja RA, Nelson V, Beevi N, Jose R. Knowledge and attitude towards organ donation in rural kerala. Acad Med J India 2014; 2: 25-7. [Google Scholar] |

| 17. | Jacob Arriola KR, Robinson DHZ, Perryman JP, Thompson N. Understanding the relationship between knowledge and african americans' donation decision-making. Patient Educ Couns 2008; 70: 242-50. Patient Educ Couns 2008; 70: 242-50.'>[Google Scholar] |

| 18. | Skumanich SA, Kintsfather DP. Promoting the organ donor card: A causal model of persuasion effects. Soc Sci Med 1996; 43: 401-8. [Google Scholar] |

| 19. | Cohen EL. 'My loss is your gain': Examining the role of message frame, perceived risk, and ambivalence in the decision to become an organ donor. Thesis, Georgia State University, 2007. Available at http://scholarworks.gsu.edu/communication_theses/26 (accessed on 14 Dec 2014). http://scholarworks.gsu.edu/communication_theses/26 (accessed on 14 Dec 2014).'>[Google Scholar] |

| 20. | Ramadurg UY, Gupta A. Impact of an educational intervention on increasing the knowledge and changing the attitude and beliefs towards organ donation among medical students. J Clin Diagn Res 2014; 8: JC05-7. [Google Scholar] |

| 21. | Petersen SR. Done vida-donate life: A surgeon's perspective of organ donation. Am J Surg 2007; 194: 701-8. Am J Surg 2007; 194: 701-8.'>[Google Scholar] |

| 22. | Gungormüs Z, Dayapoglu N. The knowledge, attitude and behaviour of individuals regarding organ donations. TAF Prev Med Bull 2014; 13: 133-40. [Google Scholar] |

| 23. | Pouraghaei M, Tagizadieh M, Tagizadieh A, Moharamzadeh P, Esfahanian S, Shahsavari Nia K. Knowledge and attitude regarding organ donation among relatives of patients referred to the emergency department. Emerg (Tehran) 2015; 3: 33-9. [Google Scholar] |

| 24. | Saleem T, Ishaque S, Habib N, Hussain SS, Jawed A, Khan AA, et al. Knowledge, attitudes and practices survey on organ donation among a selected adult population of Pakistan. BMC Med Ethics 2009 Jun 17;10:5. Available at www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6939/10/5 (accessed on 12 Dec 2014). doi: 10.1186/1472-6939-10-5. [Google Scholar] |

| 25. | Sawhney C, Kaur M, Lalwani S, Gupta B, Balakrishnan I, Vij A. Organ retrieval and banking in brain dead trauma patients: Our experience at level-1 trauma centre and current views. Indian J Anaesth 2013; 57: 241-7. [Google Scholar] |

| 26. | Coelho JC, Cilião C, Parolin MB, de Freitas AC, Gama Filho OP, Saad DT, et al. [Opinion and knowledge of the population of a Brazilian city about organ donation and transplantation]. Rev Assoc Med Bras (1992) 2007; 53: 421-5. [Google Scholar] |

| 27. | Sipkin S, Sen B, Akan S, Malak AT. Organ donation and transplantation in Onsekiz Mart Faculty of Medicine, Fine Arts and Theology: Academic staff's awareness and opinions. Adnan Menderes Univ Tip Fak Derg 2010; 11: 19-25. Adnan Menderes Univ Tip Fak Derg 2010; 11: 19-25.'>[Google Scholar] |

| 28. | Siminoff LA, Burant C, Youngner SJ. Death and organ procurement: Public beliefs and attitudes. Kennedy Inst Ethics J 2004; 14: 217-34. [Google Scholar] |

| 29. | Waiting list data: United Network for Organ Sharing 2010. Available at www.unos.org (accessed on 13 Dec 2014). [Google Scholar] |

| 30. | Azkan S, Yilmaz E. Knowledge and attitudes of patients' relatives towards organ donation. Family Commun 2009; 5: 18-29. Family Commun 2009; 5: 18-29. '>[Google Scholar] |

| 31. | Morgan SE, Stephenson MT, Harrison TR, Afifi WA, Long SD. Facts versus 'Feelings': How rational is the decision to become an organ donor? J Health Psychol 2008; 13: 644-58. J Health Psychol 2008; 13: 644-58.'>[Google Scholar] |

| 32. | Ríos A, Cascales P, Martínez L, Sánchez J, Jarvis N, Parrilla P, et al. Emigration from the British Isles to southeastern Spain: A study of attitudes toward organ donation. Am J Transplant 2007; 7: 2020-30. [Google Scholar] |

| 33. | Agbenorku P, Agbenorku M, Agamah G. Awareness and attitudes towards face and organ transplant in Kumasi, Ghana. Ghana Med J 2013; 47: 30-4. [Google Scholar] |

| 34. | López JS, Valentín MO, Scandroglio B, Coll E, Martín MJ, Sagredo E, et al. Factors related to attitudes toward organ donation after death in the immigrant population in Spain. Clin Transplant 2012; 26: E200-12. [Google Scholar] |

| 35. | Dardavessis T, Xenophontos P, Haidich AB, Kiritsi M, Vayionas MA. Knowledge, attitudes and proposals of medical students concerning transplantations in Greece. Int J Prev Med 2011; 2: 164-9. [Google Scholar] |

| 36. | Mossialos E, Costa-Font J, Rudisill C. Does organ donation legislation affect individuals' willingness to donate their own or their relative's organs? Evidence from European Union survey data. BMC Health Services Res 2008; 8: 48. Available at http://bmchealthservres.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1472-6963-8-48 (accessed on 13 Dec 2014) BMC Health Services Res 2008; 8: 48. Available at http://bmchealthservres.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1472-6963-8-48 (accessed on 13 Dec 2014) '>[Google Scholar] |

| 37. | Alashek W, Ehtuish E, Elhabashi A, Emberish W, Mishra A. Reasons for unwillingness of Libyans to donate organs after death. Libyan J Med 2009; 4: 110-13. [Google Scholar] |

| 38. | Wakefield CE, Reid J, Homewood J. Religious and ethnic influences on willingness to donate organs and donor behavior: An Australian perspective. Prog Transplant 2011; 21: 161-8. [Google Scholar] |

Fulltext Views

7,536

PDF downloads

2,046