Translate this page into:

Legal mechanisms and procedures in alleged medical negligence: A review of Indian laws and judgments

Correspondence to RANJIT IMMANUEL JAMES; ranjit_immanuel@yahoo.co.in

[To cite: Goel R, Amarnath M, James RI, Amarnath A. Legal mechanisms and procedures in alleged medical negligence: A review of Indian laws and judgments. Natl Med J India 2024;37:39–45. DOI: 10.25259/NMJI_955_2021]

Abstract

Medical malpractice suits are quite common in developed countries leading to an increase in malpractice insurance. Recent trends indicate that India is at the cusp of a medical malpractice crisis. There has been a rise in medical negligence cases filed against doctors, though often the allegations are frivolous. In such cases, doctors can be considered as the second victim of medical negligence. Members of the medical fraternity do not learn much about law during their training and are often naïve regarding various options available to counter such cases as well as relevant legal doctrines. Doctors thus not only need to remain updated on medical knowledge and skills but also obtain knowledge of legal paradigms.

We aim to raise awareness among doctors about handling negligence cases in various forums and share insights through relevant literature, court judgments and government orders. We also map the process of handling complaints, procedures followed in various courts and the different levels of remedies available for doctors.

INTRODUCTION

Negligence or malpractice in the jurisprudential context is defined as ‘a breach of a duty caused by, the omission to do something which a reasonable man (guided by those considerations which ordinarily regulate the conduct of human affairs) would do, or doing something which a prudent and reasonable man would not do’.1 This legal principle is sought for dealing with disputes relating to any professional work and holds good for medical practice also. Here the phenomenon is referred to as ‘medical negligence’.

History is replete with instances of medical negligence going back many centuries, its legal recognition, and remedies awarded including compensation and punishments. It has gained much importance in the recent past and medical negligence is addressed with connotations of a ‘pandemic’.2 There are many reasons for this development, yet the common theme that explains the scenario is the emergence of ‘culture of blame’. However, for the aggrieved party, negligence suits are an effective and sometimes the only modality of seeking reform or compensation.3

Physicians, on the other hand, are facing the brunt of this pandemic. Though not denying the existence of bad fish in the pond, it would be unfair to paint the entire medical fraternity with the same brush. Doctors often find themselves struggling to keep themselves up-to-date with the ever-expanding medical knowledge and skills. They additionally have to deal with physical and emotional burnout, pressures of the profit-driven corporate medical sector, overloaded public hospitals and lack of health infrastructure.4,5 Since the doctor is usually the only constant person who comes in direct contact with the patient, any perceived lack in the treatment process or an unfavourable outcome is blamed on the doctor’s negligence.

A doctor invests time and effort and tries her/his best to treat every patient. When the treatment for a patient fails or there is an adverse event for the patient, doctors often question themselves and the decisions made, which leads to emotional trauma. A medical negligence suit does not limit itself to financial consequences but has a variety of physical and psychological effects on the doctor.6 Wu et al. used the term ‘2nd victim’ for a healthcare professional to emphasize that the traumatic impact of an adverse event due to medical treatment does not limit itself to the patient (1st victim) but doctors are affected too (2nd victim).7 The trauma to the doctor is often enhanced by lack of knowledge and the fear of legal proceedings. Current practice of medicine requires the doctor to not only update their medical knowledge and skill but also have reasonable knowledge of legal paradigms. This becomes especially important because of the specialized nature of medical law. Here the legal doctrines guiding the medical practice can be, at times, vastly different from those adopted in routine civil and criminal litigations.8

We intend, through this article, to bridge the knowledge gap among doctors about the legalities of handling negligence cases. First, we analyse allegations of medical negligence by reviewing relevant Indian laws, court judgments (post-1995), scientific literature and government orders pertaining to this matter. Second, we attempt to outline the process of handling complaints, investigative tools used by the respective court/tribunal, and various remedies that can be sought by physicians at different levels. Finally, we suggest guidelines that may be useful for physicians to handle an allegation of medical negligence.

THE BURDEN OF PROOF: WHO?

Whenever a person claims that she/he has suffered harm due to negligence of the treating doctor and wants a legal remedy for the same, it is incumbent on her/him to prove negligence of the doctor. The National Consumer Dispute Redressal Commission (NCDRC) in its judgments in Kanhaiya Kumar Singh case and Calcutta Medical Research Institute case has held that medical negligence has to be established and cannot be presumed; and that the onus of proving negligence and deficiency in service lies on the complainant.9,10 This dictum was referred to as a settled proposition of law in the Upasana hospital case.11

In addition, there are some situations where the principle of res ipsa loquitor can be applied, i.e. when facts speak for themselves. Some examples are amputation of the wrong limb, mismatched blood transfusion, leaving a swab/instrument inside the body, etc. Here the burden of proof shifts to the respondent in civil cases. In the Jacob Matthew case, the Supreme Court has made it clear that res ipsa loquitor is a rule of evidence, helpful in fixing the onus of proof in negligence, and applicable only in civil cases. In a criminal negligence case, it has a limited application—at the trial of charges. A criminal conviction cannot be solely based on res ipsa loquitor.12

WHAT? PRE-ACTION REQUIREMENT

The first step for a patient/relative would be to obtain the treatment records from the respective health facility where alleged negligent treatment occurred. The aggrieved person/legal representative/investigating officer should give a written request to the clinical establishment for providing a copy of the treatment records of the patient. As per the Medical Council of India (MCI) regulations (2002), it is mandatory for registered medical practitioners to maintain medical records of all admitted patients for 3 years and to issue a copy of the same within 72 hours, if a request is made by the patient/authorized attendant/legal authorities.13 This is also reflected in the charter of patient rights issued by the National Human Rights Commission.14 All physicians and hospital administrators should comply with this directive, as non-compliance in this regard is taken severely by the courts. In the Maharaja Agrasen Hospital case, there was an inordinate delay of 2 years in furnishing the documents by the hospital even after receiving a written request. Citing the MCI regulations, the Supreme Court held the act to be of ‘grave professional misconduct’ and ‘deficiency in service’.15

Any tampering/overwriting of medical records—as an afterthought—should be avoided as it can directly attract criminal action suit under section 201 IPC (Indian Penal Code; destruction of evidence).

The health records are paginated, reviewed for completeness and if any document is found deficient, it is to be obtained by subsequent written requests in the same manner. The legal adviser for the claimant peruses the records to find the area of substandard treatment, frames the claimant’s complaint based on his and other witnesses’ statements (e.g. family members, if present during the medical treatment).

WHERE AND HOW?

The investigative and legal processes involved in a case of alleged medical negligence will differ based on the type of case filed. The decision on what type of case to file is usually based on the following factors: (i) nature of the negligence or the degree of the negligence; (ii) patient’s/representative’s desired outcome of legal proceedings; and (iii) the entity (individual or institution) responsible for the negligence.

Broadly, an individual’s recourse in a case of medical negligence can be either civil or criminal or both. Each type of recourse has a different outcome. Civil proceedings have the effect of monetary compensation (damages) with or without disciplinary action, whereas a criminal proceeding if proved attracts punishment to the wrongdoer in the form of imprisonment, fine, and others (seizure of assets, property, etc.). It is worth mentioning here that these proceedings are independent of each other and can be filed simultaneously. In the Dr J.J. Merchant case, the NCDRC rejected the argument suggesting delay of civil proceedings during the pendency of a criminal trial. The commission held that ‘no universal rule of law that during the pendency of criminal proceedings, civil proceedings must invariably be stayed’ (Table I).16

| Item | Civil action | Criminal action | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Desired outcome of proceedings | Compensation | Compensation | Disciplinary action against the doctor | Criminal proceeding |

| Where is complaint filed? | Civil court | District/state/national commission depending upon the compensation claimed |

Individual: State medical council Institution: Clinical Establishments Commissions |

Police station |

| Who can complain? | Aggrieved person or authorized attendant | |||

| What is required to file a complaint? | Affidavit in the form of plaint and documents that are necessary | Complaint along with supporting documents and affidavit filing by the complainant | Suo motu cognizance or formal written complaint | Formal complaint to the police about the offence |

| Who has the burden of proof? | Patient. In case of res ipsa loquitor: Doctor | Patient. In case of res ipsa loquitor: Doctor | Prosecution (Attorney of the state) | |

CRIMINAL LAW RECOURSE

As per Indian law, there is no special provision for investigating, prosecuting or punishing medical negligence under the criminal justice system. In general, medical negligence is measured in context with the general statute of the IPC and it also runs parallel with other kinds of negligence. For example, death due to rash and negligent act is an offense as per section 304A of the IPC. Here the statute does not distinguish between the act of negligence of a driver or doctor. Similar application can also be seen for sections 337 and 338 IPC, where the consequence of negligent act causes hurt and grievous hurt, respectively.17

However, the Supreme Court in various instances has dealt with the question of what may constitute criminal negligence. In Dr Suresh Gupta case, the apex court held

When a patient agrees to go for medical treatment or surgical operation, every careless act of the medical man cannot be termed as ‘criminal’. It can be termed ‘criminal’ only when the medical man exhibits a gross lack of competence or inaction and wanton indifference to his patient’s safety and which is found to have arisen from gross ignorance or gross negligence. Where a patient’s death results merely from an error of judgment or an accident, no criminal liability should be attached to it. Mere inadvertence or some degree of want of adequate care and caution might create civil liability but would not suffice to hold him criminally liable.18

The apex court took a similar stand in Jacob Mathew case. The Court highlighted the importance of mens rea as an essential ingredient. The Court held that: ‘For negligence to amount to an offense, the element of “mens rea” must be shown to exist. For an act to amount to criminal negligence, the degree of negligence should be much higher, i.e. gross or of a very high degree.’12

However, while answering a special leave petition on the requirement of establishing mens rea in a medical negligence case, a division bench of the Supreme Court held: ‘For, when it is a case of medical negligence, it need not be because of mens rea as intent. Sans mens rea in the above sense also would still constitute the offense of medical negligence.’ The apex court instructed the trial court to follow the guidelines regarding expert opinion as provided by the Supreme Court in the Jacob Mathew case.19

SUPREME COURT JUDGMENTS ON INVESTIGATION OF ALLEGED CRIMINAL NEGLIGENCE

The Supreme Court of India in Jacob Mathew case put forward certain guidelines for handling a criminal complaint against doctors.12 Any person intending to file a criminal complaint against a doctor for criminal negligence has to satisfy the conditions laid down in Jacob Mathew case. The key features of the guidelines include the following:

A private complaint may not be entertained unless the complainant has produced prima facie evidence before the Court in the form of a credible opinion given by another competent doctor to support the charge of rashness or negligence on the part of the accused doctor.

-

As per the direction of the Supreme Court, a doctor accused of rashness or negligence, may not be arrested in a routine manner (simply because a charge has been levelled against him). Unless his arrest is necessary for furthering the investigation or for collecting evidence or unless the investigation officer feels satisfied that the doctor proceeded against would not make himself available to face the prosecution unless arrested, the arrest may be withheld.

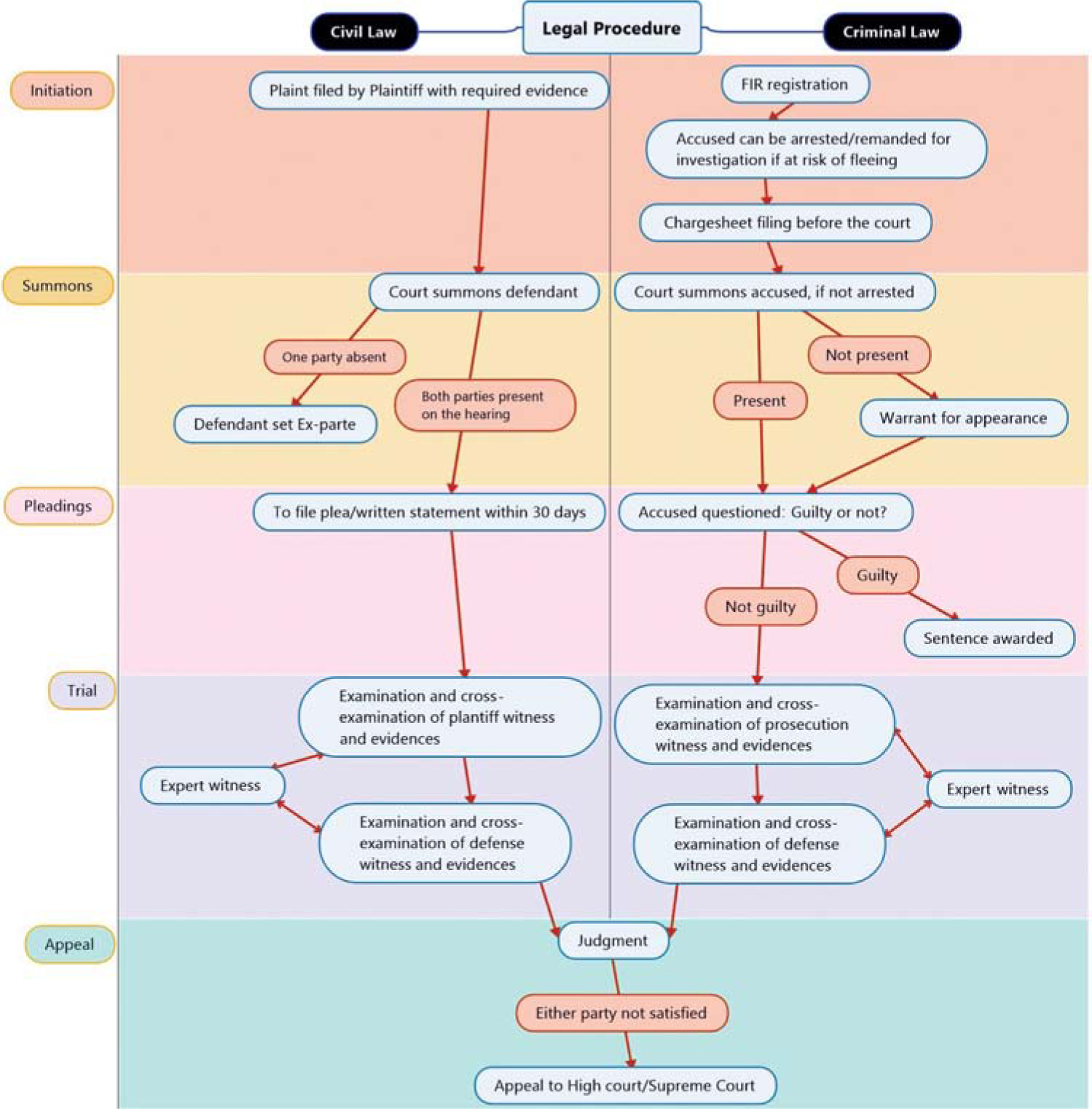

Note: In Lalita Kumari case (2013), the Supreme Court has held that FIR (first information report) need not be registered if the prima facie evidence is not proved in the preliminary inquiry.20 The procedure regarding the preliminary inquiry is shown in Fig. 1.

In case negligence is found by the medical board, the police can proceed to register the case against the doctor and file a final report (including chargesheet) in the criminal court. Later, the procedure of a criminal case will be followed as shown in Fig. 2.

- Preliminary inquiry procedure

- Legal proceedings in civil and criminal courts FIR first information report

Remedies available to the doctor

If a physician believes that the charges of negligence brought against him do not amount to criminal negligence but FIR and subsequent proceedings have been initiated against him; he/she can approach the High Court for quashing the criminal proceedings under section 482 CrPC. In the case of Dr Mohd Azam Hasin, Allahabad High Court held that though the charges made against the accused doctor can be contested for civil negligence or liability but not for the criminal one. The High Court accepted the prayer of the accused doctor to quash the entire criminal proceedings as well as the impugned summoning order passed by the lower court.21

In case the High Court also denies relief from a criminal proceeding, the aggrieved physician can approach the Supreme Court by way of criminal appeal. In Daljit Singh Gujral case, an appeal filed before the High Court, to quash the criminal proceeding, was not entertained, but the Supreme Court ordered to set aside the judgment and order of the Judicial Magistrate and also ordered the High Court to hear the criminal petition afresh.22

The Supreme Court in Jayshree Ingole case quashed the criminal action against the doctor and held that the severity of negligence may attract a tort liability but not the criminal one.23

PRELIMINARY INVESTIGATION AND ROLE OF MEDICAL BOARD

Investigation of medical negligence cases falls into two categories, i.e. cases with fatal outcomes and non-fatal outcomes (Fig. 1).

On receipt of information, the police officer makes a diary entry to hold a preliminary inquiry about the case. The investigating officer records the statements from the complainant and witnesses and obtains treatment records of the victim from the respective healthcare facility and attendants. Appendix 1 (available at www.nmji.in) has the list of some of the records that may be sought.

In a case where the death of the patient has occurred, the custody of the body is transferred to the investigating officer of the case. The body is preserved in the mortuary of a hospital for temporary storage. The post-mortem examination may be conducted at a different hospital if needed and based on the government orders of the particular state.

The autopsy examination report along with other supportive medical evidence is put forward to a medical board to comment upon the presence or absence of medical negligence in the case. This medical board is constituted by the state medical council either on a case-to-case basis or jurisdiction-wise such as a ‘District Medical Board’ or an apex body at the level of the state.

The medical board, on hearing both parties and examining documentary evidence and/or the patient, renders its opinion as to whether there was medical negligence by doctor/institution or not. Based on the opinion of the board, the investigating officer either closes the case or registers a complaint under applicable legal sections such as S.304A/337/338 IPC or any other relevant section against the doctor/institution.

CIVIL LAW RECOURSE

Negligence is a recognized tort law principle that is based on the premise of compensation. Here the individual can seek financial compensation for the suffered loss, in addition to exercise of regulatory control. The aggrieved individual can also have the same recourse in the case of a claim for damages towards institutions, and the regulatory control can be exercised by filing a formal complaint under the Clinical Establishment Act or its equivalent legislature in the state.24

An individual suffering damage can claim damages by approaching the civil court. Here a suit is filed by the plaintiff (patient–complainant) against a defendant (doctor–defendant). The civil court operates under the provisions of the Civil Procedure Code (1908) and the Indian Evidence Act. The court fees charged are based on the compensation amount asked by the plaintiff and legal counsel is a prerequisite. Following the procedure described in Fig. 2, the court either awards a compensation or dismisses the case. Any appeal against the judgment of the district court can be filed in the High Court of the state and Supreme Court in that order. Before the 1995 Supreme Court judgment in the Indian Medical Association case, all cases of medical negligence were dealt primarily by the civil courts.25 The case of Ashish Majumdar filed in 1991 is a good example. Here the patient, following a negligence suit against the hospital, requested the Supreme Court to revise the compensation amount granted. The trial court awarded `7 lakh and it was raised tò11 lakh by the High Court. The Supreme Court dismissed the appeal in 2014.26

In case of a claim for damages, the same can be achieved at a speedy and easier method by way of a Consumer Complaint before the Consumer Dispute Redressal Commissions.

CONSUMER LAW RECOURSE

The Consumer Protection Act (CPA) was passed in 1986.27 In the landmark Indian Medical Association case, the Supreme Court held that the services rendered by medical practitioners fall under the ambit of the CPA.25 The CPA was introduced to enable faster delivery of justice and to minimize the requirements of legal advisors in the process of seeking justice by the general public. The Act mandates using summary procedures for dealing with consumer grievances. Many a time, the Supreme Court has been approached to provide clarity on various aspects of the consumer court’s functions and procedures undertaken by consumer fora; such as transfer of the case to civil court in case of delay/ongoing criminal prosecution, the applicability of provisions of the Evidence Act, admission of witness/expert opinion in the absence of cross-examination, etc.

In 2019, a new legislation Consumer Protection Act (2019) was passed and the older Act of 1986 was repealed.28 The new Act has incorporated alternate dispute redressal mechanisms. A special chapter dedicated to mediation is included in the new Act (Fig. 3).28

- Consumer court procedures for alleged medical negligence (Consumer Protection Act, 2019)

PROCEDURE FOLLOWED IN CONSUMER COURTS

According to the new CPA (2019), if elements of settlement are present, then the case will be referred to a mediation cell associated with the respective consumer redressal (district/state/national) commissions. The mediation rules published under the provisions of the Act regard ‘medical negligence resulting in grievous hurt or death’ as one of the exceptions, where matter cannot be referred for mediation.29 In other cases, the decision for referring to mediation is left to the discretion of the president of the respective commission. The president of the commission takes the consent of both parties before referring the matter to a mediator from the list of nominated mediators and any court fees if submitted are refunded. If a solution is made out by mediation, the same will be passed as a judgment by the appropriate commission within 7 days.28

The referral to a mediator does not bind the parties as they can opt-out of the mediation at any stage or if no consensus is reached between the parties. If mediation fails, the case will proceed as a regular case which will either result in an award of compensation or a dismissal of the complaint. If either party is unhappy with the ruling, an appeal can be made to the higher commissions such as state and NCDRC, and a final appeal against the order of the NCDRC can be made to the Supreme Court.

ROLE OF STATE MEDICAL COUNCIL

Disciplinary action against the doctor

In addition to the charges of negligence, a formal complaint of misconduct and request for punishment with disciplinary action can also be filed against a registered medical practitioner. Following a complaint by public/police/colleague/office or a court conviction, the state medical council takes cognizance of the offense and investigates the matter to decide appropriate action (Fig. 4).30–32

- Complaint handling procedure by state medical council

TESTIMONY FROM MEDICAL EXPERT/PANEL IN DIFFERENT SITUATIONS

Legal professionals are often not familiar with the minutiae of medical management and hence need the assistance of medical experts to interpret medical records. When it involves assessment of a case of alleged medical negligence, the opinion of an expert from the same specialty is an important part of the investigation to assess the standard of care. The Supreme Court, in the case of V. Kishan Rao, identified two functions of an expert. The first is to explain the technical issues with the clarity that a common man can understand and the other is to assist the fora in deciding whether the act or omission of the doctor or hospital constitutes negligence or not.33

In the Martin D’Souza case (2009), the Supreme Court has said that the guidelines laid down by the apex court in Jacob Mathew case should be extended to consumer cases as well, i.e. medical experts’ opinions should be obtained before deciding the case.34 But later in 2010, in Kishan Rao’s case the apex court held that it is not necessary for consumer fora to get experts’ opinion in every case, but in case of complex issues, opinion can be sought. In Srimannarayana case, the recommendations of the Martin D’Souza case were sought to be applied in the consumer cases and an appeal regarding the deficiency of expert opinion was filed before the Supreme Court. The Court dismissed the appeal in 2013.35

In 2017, MCI proposed a set of guidelines to be observed by prosecuting agencies for protecting doctors against frivolous complaints/prosecution. These guidelines suggested the formation of a medical board at the district, division and state levels to examine the cases forwarded by the prosecuting agencies.36 Recently, the National Medical Commission (NMC), which has taken over the functions of MCI in 2020, has published a set of fresh guidelines under a similar heading.37 These guidelines have considered some interesting developments. Here, the NMC has not only fixed responsibility on the Forensic Medicine department to function as the nodal department in these cases but also decreased the time limit at various steps (2 weeks, earlier 3–4 weeks) for faster expedition of the inquiry process. In addition, the divisional medical board functioning above the level of the district board has been dispensed with and now the aggrieved person can directly approach the state medical board, if dissatisfied with the decision of the district medical board.

We are yet to observe an impact of these revised guidelines. However, if we go by the earlier practice, we find the standards are not uniform across states. We sought information from colleagues by personal communications—about the investigating procedure in medical negligence followed in different parts of the country. The government orders from various states in this regard are given in Table II.

| State | Investigating/reviewing body | Apex body | Time limit to make a decision | Autopsy | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State Medical Council | District Medical Board | |||||

| Delhi | Yes | No | No | NA | Panel of three forensic experts | |

| Maharashtra | No | Yes | No | 15 days | Multidisciplinary team | |

| Tamil Nadu | NA | NA | NA | NA | Panel of forensic experts | |

| Karnataka | Yes | No | No | 60 days | Panel of forensic experts/multidisciplinary team | |

| Haryana | No | Yes, 6-member board | No | NA | NA | |

| Punjab | No | Yes | No | NA | Multidisciplinary team | |

| Kerala | No | Yes | Yes | 30 days | Panel of forensic experts | |

NA not applicable

CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Medical negligence remains a specialized area of law and poses new challenges for the Indian legal system. In the absence of a dedicated statute on the subject, there are grey areas in the understanding of medical negligence among not only patients but also professionals from both medicine and law. As the laws governing medical services are expanding, the process of handling complaints also needs to be defined, standardized, accepted and improved upon when needed; because a lag or bias in this regard will adversely impact the function of professionals and society. Self-regulation is one of the pillars of medical professionalism and it imparts added responsibilities on the professional bodies for proactive involvement in matters of medical negligence. Utmost care is required for these matters as an allegation of medical negligence does not limit its impact to only one party in the dispute, rather both parties may be the victims at the same time.

In view of the current understanding and practice, we recommend the following:

Regulatory bodies such as state medical councils and the NMC should work together as a team to create a policy regarding the investigation of medical negligence cases in various scenarios including fatal outcomes.

The guidelines published by the NMC should be adopted in a uniform manner and regularly updated. State governments and institutional administration should take measures so that procedure as well as timelines are followed uniformly.

The standards of investigations published and accepted internationally can be adopted after tailoring them to the needs of our country.

Interdisciplinary participation should be encouraged in these investigations. Professionals from various related specialties should also be included in the team of experts.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank Dr Latif Rajesh Johnson for his valuable comments and critical inputs.

References

- Law of torts In: Singh GP, ed. Law of Torts (24th ed). Gurugram: Lexis Nexis; 2002. p. :441-2.

- [Google Scholar]

- Medical malpractice and legal medicine. Int J Legal Med. 2013;127:541-3.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Towards a history of medical negligence. Lancet. 2010;375:192-3.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Physician burnout: Are we taking care of ourselves enough! J Ment Health Hum Behav. 2018;23:76-7.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The impact of complaints procedures on the welfare, health and clinical practise of 7926 doctors in the UK: A cross-sectional survey. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e006687.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medical error: The second victim. The doctor who makes the mistake needs help too. BMJ. 2000;320:726-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Law and the medical-man: The challenges of an expanding interface In: Beran R, ed. Legal and forensic medicine. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer; 2013. p. :497-516. Available at https://link.springer.com/referenceworkentry/10.1007/978-3-642-32338-6_28 (accessed on 17 May 2021)

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- MCI. Code of Medical Ethics Regulations. MCI India. 2002. Available at www.mciindia.org/CMS/rules-regulations/code-of-medical-ethics-regulations 2002 (accessed on 21 Aug 2020)

- [Google Scholar]

- Charter of Patients’ Rights for adoption by NHRC. Patients’ rights are Human rights! Available at http://clinicalestablishments.gov.in/WriteReadData/8431.pdf (accessed on 20 Aug 2020)

- [Google Scholar]

- Medical negligence: Indian legal perspective. Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 2016;14:S9-S14.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mens Rea as intent not required in medical negligence cases: Supreme Court. Available at www.livelaw.in/top-stories/supreme-court-medical-negligencecase-mens-rea-as-intent-179110 (accessed on 9 Aug 2021)

- [Google Scholar]

- Ashish Kumar Mazumdar v. Aishi Ram Batra Charitable Hospital Trust, (2014) 9 SCC 256.

- [Google Scholar]

- Vij K. Medical education vis-a-vis medical practice In: Textbook of forensic medicine and toxicology: Principles and practice (6th ed). Delhi: Elsevier India; 2014. p. :336.

- [Google Scholar]

- Judicial procedure of state council In: The essentials of forensic medicine and toxicology (34th ed). Delhi: Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers; 2017. p. :25-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Judicial function of state medical council In: Dr Subrahmanyam’s Medical Jurisprudence & Toxicology (1st ed). Allahabad: Law Publishers (India) Pvt. Ltd; 2013. p. :29.

- [Google Scholar]

- Guidelines for protecting doctors from frivolous or unjust prosecution against medical negligence In: Minutes of Meeting: Executive committee. 2017. p. :35-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Ethics and Medical Registration Board. National Medical Commission. Guidelines for protecting doctors from frivolous or unjust prosecution against medical negligence. vide NMC/MCI/EMRB/C-12015/0023/Ethics/022426 Dated 29.09.2021.

- [Google Scholar]