Translate this page into:

Multispecialty consensus statement for primary care management of diabetic foot disease in India

2 Department of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, Kokilaben Dhirubhai Ambani Hospital, Mumbai, Maharashtra, India

3 Department of Plastic Surgery, Army Hospital (Research and Referral), Delhi, India

4 Department of Surgery, Dr Balabhai Nanavati Hospital, Global Hospital, Hinduja Hospital, Mumbai, Maharashtra, India

5 Department of Vascular Surgery, Government Kilpauk Medical College, Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India

6 Diabetic Foot Specialist, Aashirwad Hospital, Mumbai, Maharashtra, India

7 Consultant General Surgeon and Phlebologist, Dr Gore's Clinic, Mumbai, Maharashtra, India

8 Department of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery, Nizam's Institute of Medical Sciences, Hyderabad, Telangana, India

9 Department of Plastic, Aesthetic and Reconstructive Surgery, Medanta Medicity, Gurgaon, Haryana, India

10 Department of Vascular Surgery and Endovascular Sciences, Vijaya Hospital, Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India

11 Department of Plastic Surgery, Hand and Reconstructive Microsurgery and Burns, Ganga Hospital, Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu, India

12 Department of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery, M.S. Ramaiah Medical College and Hospitals, Bengaluru, Karnataka, India

13 Consultant Plastic Surgeon, S.L. Raheja Hospital, Mumbai, Maharashtra, India

14 Department of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery, Dr Srikanth Vijayasimha's Vascular Clinic, Bengaluru, Karnataka, India

15 Department of Surgery, Jorhat Medical College, Guwahati, Assam, India

16 Department of Aesthetic and Reconstructive Plastic Surgery, MAX Healthcare, Delhi, India

17 Limb Salvage Team Leader, Sou. Mandakini Team Memorial Hospital, Hubli, Karnataka, India

18 General Surgeon, Diabetic Foot Clinic, Mumbai, Maharashtra, India

Corresponding Author:

Arun Bal

Talwalkar Polyclinic, 153-B Hindu Colony, Opposite Ruia College, Matunga, Mumbai 400019, Maharashtra

India

arunbal@gmail.com

| How to cite this article: Bal A, Chaudhari C, Langer V, Vyas D, Thulasikumar G, Ruke M, Gore MA, Ramakrishna P, Khazanchi RK, Subrammaniyan S R, Sabapathy S R, Desai S, Vaidya S, Vijayasimha S, Jain S, Chaudhary S, Kari S, Rege T. Multispecialty consensus statement for primary care management of diabetic foot disease in India. Natl Med J India 2017;30:82-88 |

Introduction

India ranks second in terms of the number of people with diabetes in the world[1]—an estimated 66.8 million with an alarming rise in the incidence of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), especially among obese people and increasing diabetes-associated complications. In people with diabetes a common complication is diabetic foot disease (DFD). Foot disorders are the leading cause of hospitalizations and amputations with varying prevalence in different countries. In the USA, up to 120 000 amputations are performed every year. People with diabetes have a 10-fold higher risk of amputation compared to those who do not have diabetes.[2] Foot ulcerations affect 1 in 4 people with diabetes[3] and approximately 15% of diabetic foot ulcers result in amputation.[4] While diabetes-related amputations occur every 30 seconds, about 85% of these are preventable.[5] Due to social, religious and economic reasons, many people in India walk barefoot. Moreover, poverty and illiteracy lead to the use of inappropriate footwear and late presentation of foot lesions.[3] Diabetic foot care is one of the most ignored aspects of diabetes care in India and many other countries.[4],[5],[6] Patients try home remedies or visit non-physicians before visiting their physicians for treatment.

Amongst Indian urban and rural households, 70% of all visits of patients are to private-sector providers (over public).[7] These include primary healthcare physicians, non-physicians or non- degree allopathic practitioners (NDAPs).[8]

Other factors that add to the problem include low level of medical training among healthcare providers at the primary care level,[7] poor adherence to clinical checklists,[7] absence of DFD in the curriculum of healthcare practitioners (HCPs) and low adoption of existing national and international guidelines due to a non- established patient referral/consultation pathway in DFD. There is also the problem of turf-sharing between multiple specialists, who manage these patients currently. These include plastic surgeons, general surgeons, vascular surgeons, orthopaedic surgeons, podiatrists, diabetes specialists, general practitioners, etc. Evidence-based guidelines or peer-reviewed protocols for management of DFD at the primary healthcare level do not exist in India.

It has been established that reduction in the frequency of foot complications, incidence of major leg amputation and in-patient admissions can be achieved by adopting a rational and multidisciplinary approach in the management of DFD.[9]

With this background, the expert panel of the Wound Health Council (WHC), comprising representatives from the aforementioned specialties attempted to objectively analyse the existing literature, critically review the national and international guidelines and form an evidence-based consensus for DFD with an objective to guide primary HCPs in India (usually the first point of contact for the patient) with the requisite tools to assess, diagnose, manage and prevent DFD and related complications in their clinical practice.

While the recommendations in this consensus are not intended to dictate the care of all affected patients by primary HCPs, the goal is to provide evidence-based, practical clinical guidance for general practice, which if incorporated into patient management protocols, may lead to better outcomes and a reduction in limb amputations due to diabetes.

Prevention and Management of DFD

The WHO criteria for the diagnosis of diabetes is fasting plasma glucose (FPG) >126 mg/dl or plasma glucose >200 mg/dl at 2 hours after a 75 g oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT).[10]

The circulatory and neuropathic sequelae of diabetes can turn minor breakdowns into severe ulcerations, which may need amputation. Evidence suggests that about 15% of all people with diabetes will develop an ulcer, and about half of all amputations start with an ulceration.[11] Survival after amputation is poor. Perioperative mortality is 10%–15%, even in developed nations such as the UK.[12]

Early Diagnosis And Management Of DFD

Identification of historical and/or physical findings can improve the prognosis and lead to a favourable outcome through appropriate treatment and early referral. The importance of recognition of risk factors and treatment of DFD is crucial to prevent potential limb and/or life-threatening complications.

Early detection and effective management of diabetic foot ulcers can reduce complications, including preventable amputations and possible mortality.[13] Long-term efforts have reduced amputation rates by 37%–75% in different European countries over 10–15 years.[14] Even when healed, diabetic foot should be regarded as a lifelong condition and managed accordingly to prevent recurrence.[14]

Recommendations For Diagnosis And Assessment Of DFD

Effective management of DFD requires skills to diagnose, manage, treat and counsel the patient. Assessment of DFD includes carefully recording and reviewing of patient's history, symptoms and physical signs with the results of necessary investigative procedures.

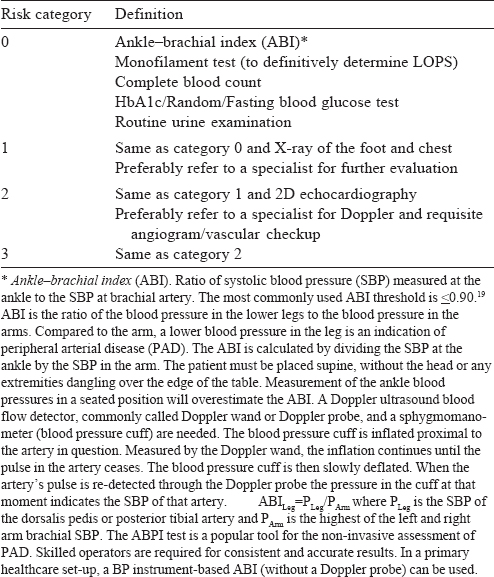

An assessment tool may prove to be valuable in evaluating the patient and determining the risk level (Appendix 1; available at www.nmji.in). It is recommended that for adequate evaluation clinicians should at least have the following as a part of their bedside diagnostic armamentarium:[15],[16] (i) 128 Hz tuning fork and (ii) 10 g monofilament.

Medical history

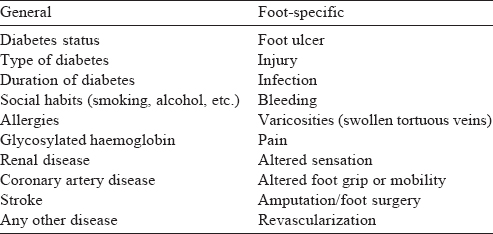

A thorough medical and foot history must be obtained from the patient.[15],[16] The history of the patient should cover several issues related to DFD, including some general and specific points [Table - 1]. History of neuropathic and peripheral vascular symptoms should be elicited. History of smoking is important because it may be a risk factor for DFD. Though history plays an important role, it alone is not sufficient for a complete assessment of the risk factors for DFD. A thorough examination of the patient should also be done.

Examination

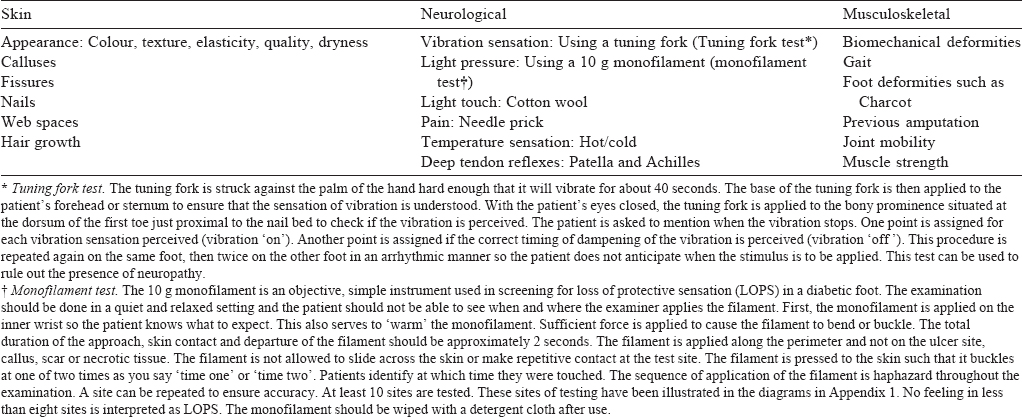

Along with general physical examination, such as height and weight, all patients with diabetes require a thorough examination of the foot.[16],[17] Patients should be examined after removing their shoes and socks to avoid missing any foot deformity. Gait and foot arch during movement must be observed too, for abnormal pressure points and deformities. During physical examination of the foot, skin, neurological, vascular and musculoskeletal examination should be done. Dermatological examination should include inspection of dryness or change in skin status and signs of infection or ulceration. Any deformity or wasting should be looked for during musculoskeletal examination. In addition to examination of the foot, footwear should also be examined[5] as it may be responsible for the foot ulcer—especially commonly seen with the use of open slippers or tight Velcro straps.[3],[6] Vascular assessment of the foot should be done to check adequacy of blood supply [Table - 2]. The tuning fork and monofilament tests are important in diagnosing loss of protective sensation (LOPS).

Generally, a patient with one or more comorbid conditions should undergo careful foot examination at least once in a year. Appendix 1 (available at www.nmji.in) is a simple tool adapted and simplified from international guidelines,[15],[18] which could be of help in a holistic, systemic and local assessment of the patient with DFD.

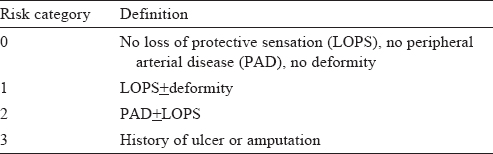

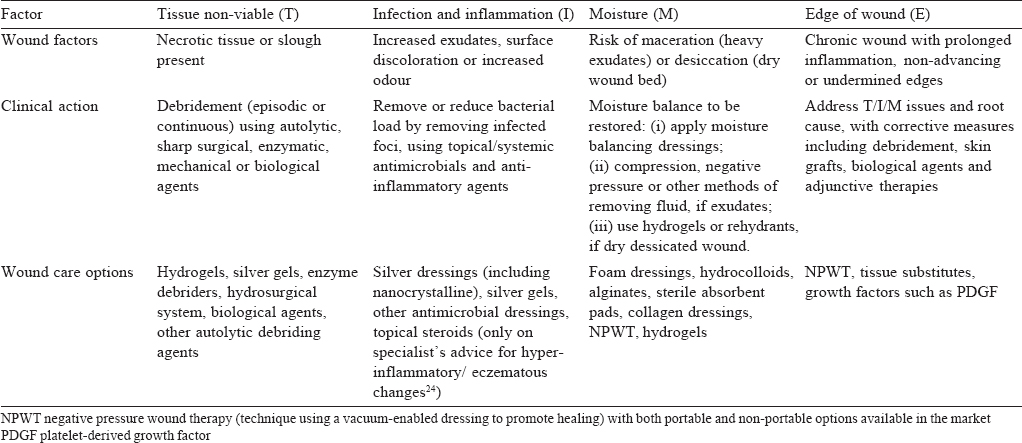

On the basis of history, physical examination and assessment, DFD can be categorized into four categories [Table - 3]. Investigations can be recommended based on the risk categorization [Table - 4]. Appropriate management, including referral or specialist consultation, must be planned.

Recommendations for the management of DFD The goal of treatment of DFD is to obtain wound healing and closure as early as possible. Complete remission and non-recurrence can lower the chances of amputations in patients with DFD.[21] The essential components of DFD management are:

- Wound management

- Medical management: Glycaemic and infection management

- Lifestyle modifications: Although recommendations are made here, other currently available therapies should not be ruled out.

Wound management

Off-loading, i.e. effective reduction in pressure, is the main objective of any treatment programme for healing of diabetic foot wounds.[22] Off-loading is essential and often considered the most important component of the management of predominantly neuropathic plantar foot wounds. The neuropathic plantar foot wounds may heal satisfactorily, when off-loaded.[22] With effective off loading, healing can generally be achieved in a period of 6-12 weeks.[22] The patient may be gradually transferred to appropriate footwear, which may need extra depth or in the case of severe deformity, custom moulded.[23]

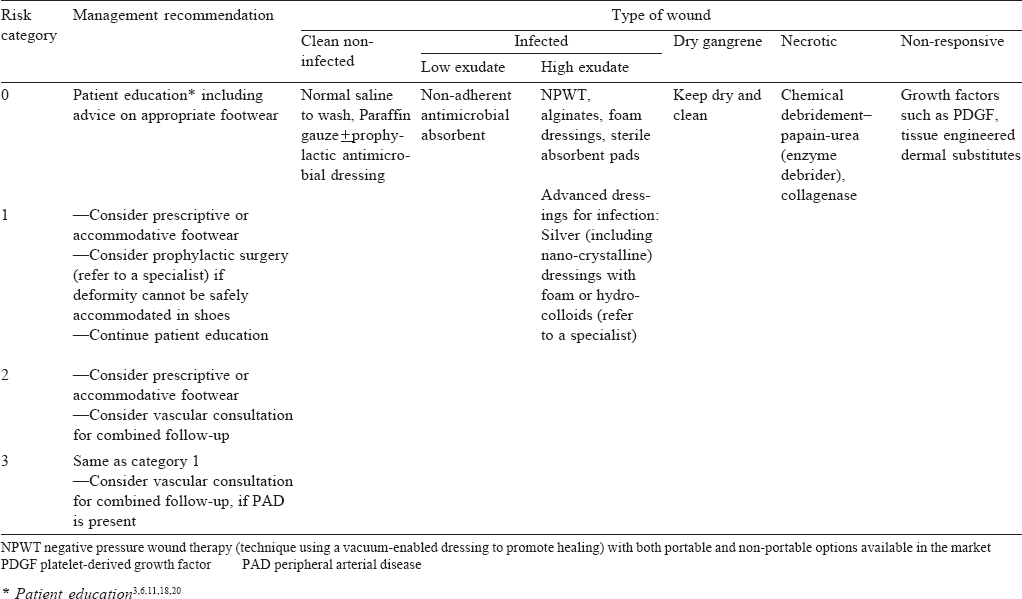

Local wound care should be addressed based on the TIME principle for wound bed preparation,[24],[25],[26] (Tissue, Infection and Inflammation, Moisture and Edge of wound; [Table - 6].

Treatment of DFD according to foot examination risk categorization, along with points of referral or specialist consultation, is provided in [Table - 5].

Diabetic Charcot foot

Charcot foot (neuropathic osteoarthropathy) is a progressive condition characterized by joint dislocation, pathological fractures and severe destruction of the foot anatomy[27] due to involvement of bones, joints and soft tissues of the foot and ankle.[28] This condition can result in debilitating deformity or even amputation.[27],[28] No single cause can be pinpointed for the development of Charcot foot. Different factors and events such as uncontrolled inflammation in the foot, osteolysis and neuropathy may be associated with its pathogenesis.[28]

Recommendations for the diagnosis and management of Charcot foot

The diagnosis of active Charcot foot is done based mainly on the patient's history and clinical examination. For confirmation of the diagnosis, imaging is required. X-rays may detect abnormal findings such as subtle fractures or subluxations. In case, no changes are seen on X-rays and the clinician has a strong suspicion then MRI or nuclear imaging may be done to confirm the clinical suspicions.[28]

Although immobilization and stress reduction are the mainstay of treatment for Charcot foot, immediate referral of the patient to a diabetic foot specialist for further evaluation, diagnosis and treatment is recommended.[27]

Medical Management

Glycaemic control

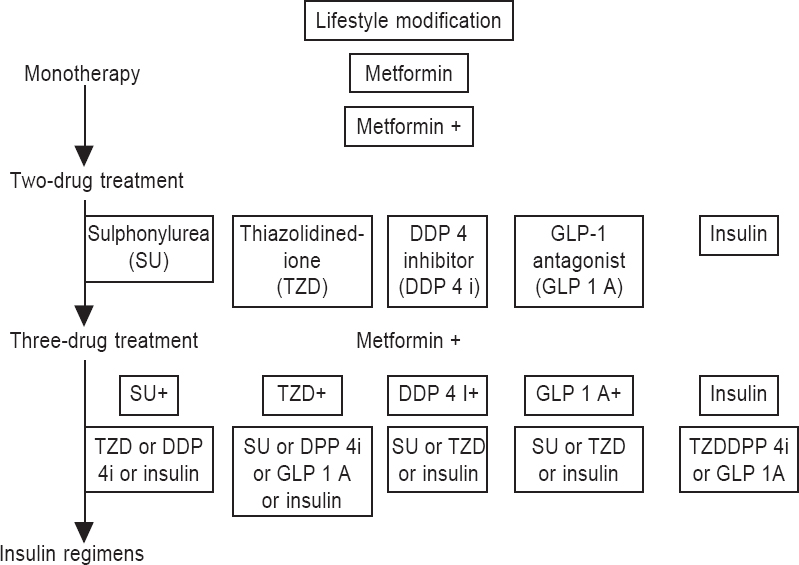

Though glycaemic control is usually supervised by a diabetologist or specialist consultant, one must be aware of the general norms and overall guidelines. The aim is to maintain blood glucose between 140 and 180 mg/dl, which could be self-monitored too. However, the glycaemic targets and blood glucose-lowering therapies are required to be individualized. Similarly, HbA1c targets should be individualized and monitored at least twice a year, since it is a good indicator of consistent blood glucose control over the past 2–3 months. Diet, exercise and education are the foundation of any T2DM therapy programme. Ultimately, many patients will require insulin therapy alone/in combination with other agents to maintain glycaemic control [Figure - 1].[29]

|

| Figure 1. Possible combinations of anti-hyperglycaemic therapy |

Infection management

Foot infections are common and serious complications in people with diabetes, due to predisposition to infections and poor healing. Patients may present with either local and/or systemic signs of infections. Local signs may include pain or tenderness (might be absent in neuropathy), redness, local oedema, foul smelling purulent discharge, whereas systemic signs may include fever, chills, anorexia, nausea, and sometimes change in mental status.[30]

Medication history should include use of past or current antibiotics by the patient.

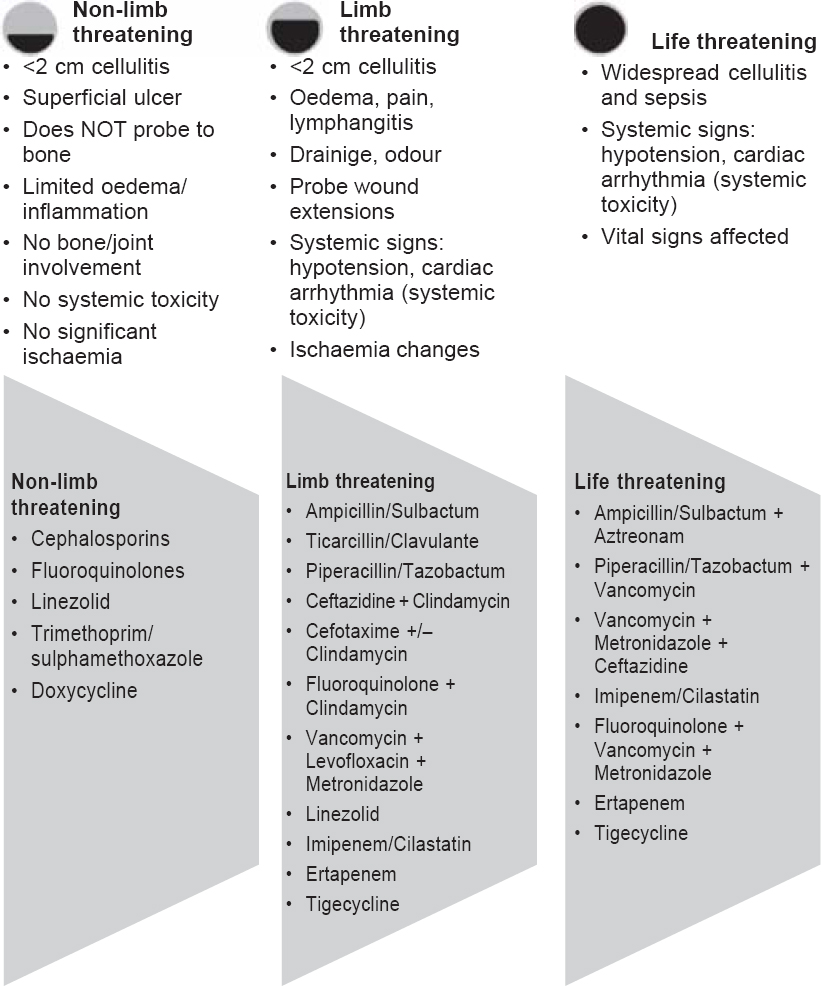

Limb infections may be classified into different categories based on severity as below.[31]

The wound management may be broadly divided into medical and surgical management.

Medical management includes use of appropriate antimicrobial therapy for the diabetic wound [Figure - 2], which may be used based on the wound category, with advice from a specialist. An antibacterial agent active against Gram-positive cocci especially methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) may be needed in high-risk patients. Patients with gangrenous and foul- smelling discharge from the wound may need treatment with anti- anaerobic agents. However, the definitive therapy should be selected based on the results of culture and sensitivity analysis.[30] Moderate-to-severe wound infections in DFD often needs incision, drainage and debrid ement of non-viable soft tissue and bone. A note of caution would be to avoid use of strong medications or antiseptics such as dettol or iodine DFD.[12],[18]

|

| Figure 2. Management of infection |

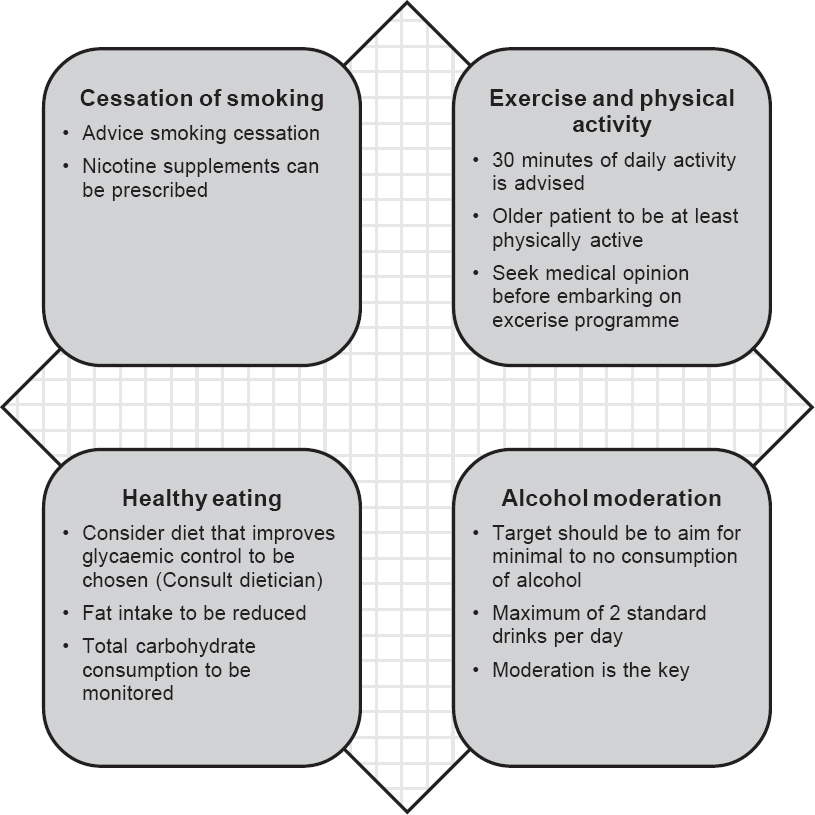

Lifestyle modifications

Lifestyle modifications such as diet, exercise, cessation of smoking and moderation of alcohol are essential components of management of DFD[29],[32] [Figure - 3]. Cessation of smoking should be encouraged in order to decrease the risk of vascular complications.[33]

|

| Figure 3. Lifestyle modifications |

Recommendations for prevention of DFD

Identifying risk factors is critical for effective prevention of foot disease in people with diabetes.

Based on the presence or absence of risk factors, people with diabetes may be broadly classified into two categories: low risk and high risk. Based on the risk category, the patient may be given an action plan [Table - 7]. Annual foot examination is recommended for all patients with diabetes in order to identify risk factors which may lead to DFD while those with high-risk of foot disease should undergo more frequent foot examination. Feet of patients with neuropathy should be inspected at every visit, as distal symmetric polyneuropathy is an important predictor for foot ulcer.[20]

Summary

Over the years, there has been an increase in the prevalence of diabetes in India and the numbers are continuously rising. DFD is a neglected aspect of diabetes care in India because of various reasons including absence of awareness, training, guidance or peer-reviewed protocols for management of DFD at the primary care level. Most diabetic foot amputations are preventable with an early diagnosis and a multidisciplinary approach. Timely diagnosis with simple methods, assessment with easy tools and treatment, with judicious referral are essential to prevent complications of DFD and must be started at the primary physician interface. The treatment of DFD consists of local wound care in accordance with the TIME principle, overall glycaemic and infection management with various traditional and advanced wound care options, and lifestyle considerations for the patient. With the tools and approach outlined along with key recommendations, which aims at equipping the first-point contact for DFD with appropriate protocols at the primary healthcare level, it is hoped that the burden and morbidity related to DFD in India would decrease.

Conflict of interest:

The development of this consensus statement was supported by an educational grant from Smith & Nephew Healthcare Pvt. Ltd., India with no academic or scientific influence or commercial liability with the participating experts.

| 1. | IDF Diabetes Atlas: Sixth edition. Basel, Switzerland: International Diabetes Federation; 2013. Available at http://www.idf.org/sites/default/files/Atlas-poster- 2014_EN.pdf (accessed on 5 Dec 2014). [Google Scholar] |

| 2. | Jain AKC, Varma AK, Mangalanandan, Kumar H. Major amputations in diabetes— An experience from diabetic limb salvage centre in India. J Diabetic Foot Complications 2012; 4: 63–6. [Google Scholar] |

| 3. | Singh N, Armstrong DG, Lipsky BA. Preventing foot ulcer in patients with diabetes. JAMA 2005; 293: 217–28. [Google Scholar] |

| 4. | Sanders LJ. Diabetes mellitus: Prevention of amputation. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc 1994; 84: 322–8. [Google Scholar] |

| 5. | Boulton AJM, Vileikyte L, Ragnarson-Tennvall G, Apelqvist J. The global burden of diabetic foot disease. Lancet 2005; 366: 1719–24. [Google Scholar] |

| 6. | Shankhdhar K, Shankhdhar LK, Shankhdhar U, Shankhdhar S. Diabetic foot problems in India: An overview and potential simple approaches in a developing country. Curr Diab Rep 2008; 8: 452–7. [Google Scholar] |

| 7. | Das J, Holla A, Das V, Mohanan M, Tabak D, Chan B. In urban and rural India: A standardized patient study showed low levels of provider training and huge quality gaps. Health Aff Millwood) 2012; 31: 2774–84. [Google Scholar] |

| 8. | Gautham M, Binnendijk E, Koren R, Dror DM. ‘First we go to the small doctor’: First contact for curative health care sought by rural communities in Andhra Pradesh and Orissa, India. Indian J Med Res 2011; 134: 627–38. [Google Scholar] |

| 9. | Thomson FJ, Veves A, Ashe H, Knowles EA, Gem J, Walker MG, et al. A team approach to diabetic foot care: The Manchester experience. The Foot 1991; 1: 75–82. [Google Scholar] |

| 10. | World Health Organization. Definition and diagnosis of diabetes mellitus and intermediate hyperglycemia: Report of a WHO/IDF consultation. Geneva: WHO; 2006 Available at www.who.int/diabetes/publications/Definition%20and%20 diagnosis%20of%20diabetes_new.pdf (accessed on 5 Dec 2014). [Google Scholar] |

| 11. | Boike AM, Hall JO. A practical guide for examining and treating the diabetic foot. Cleve Clin J Med 2002; 69: 342–8. [Google Scholar] |

| 12. | Jeffcoate WJ, Harding KG. Diabetic foot ulcers. Lancet 2003; 361: 1545–51. [Google Scholar] |

| 13. | Alavi A, Sibbald RG, Mayer D, Goodman L, Botros M, Armstrong DG, et al. Diabetic foot ulcers: Part II. Management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014; 70: 21–4. [Google Scholar] |

| 14. | Vuorisalo S, Venermo M, Lepantalo M. Treatment of diabetic foot ulcers. J Cardiovasc Surg (Torino) 2009; 50: 275–91. [Google Scholar] |

| 15. | Boulton AJ, Armstrong DG, Albert SF, Frykberg RG, Hellman R, Kirkman MS, et al. Comprehensive foot examination and risk assessment: A report of the task force of the foot care interest group of the American Diabetes Association, with endorsement by the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists. Diabetes Care 2008; 31: 1679–85. [Google Scholar] |

| 16. | Armstrong DG, Lavery LA. Clinical care of the diabetic foot. American Diabetes Association; 2005. [Google Scholar] |

| 17. | Kaveeshwar SA, Cornwall J. The current state of diabetes mellitus in India. Australas Med J 2014; 7: 45–8. [Google Scholar] |

| 18. | Frykberg RG, Zgonis T, Armstrong DG, Driver VR, Giurini JM, Kravitz SR, et al; American College of Foot and Ankle Surgeons. Diabetic foot disorders: A clinical practice guideline (2006 revision). J Foot Ankle Surg 2006; 45 (5 Suppl):S1-S66. [Google Scholar] |

| 19. | Aboyans V, Criqui MH, Abraham P, Allison MA, Creager MA, Diehm C, et al. ; American Heart Association Council on Peripheral Vascular Disease; Council on Epidemiology and Prevention; Council on Clinical Cardiology; Council on Cardiovascular Nursing; Council on Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention, and Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia. Measurement and interpretation of the ankle–brachial index. A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2012; 126: 2890–909. [Google Scholar] |

| 20. | American Diabetes Association. Preventative foot care in people with diabetes. Diabetes Care 2003; 26 (Suppl 1):S78–S79. [Google Scholar] |

| 21. | Markowitz JS, Gutterman EM, Magee G, Margolis DJ. Risk of amputation in patients with diabetic foot ulcers: A claims-based study. Wound Repair Regen 2006; 14: 11–17. [Google Scholar] |

| 22. | Armstrong DG, Nguyen HC, Lavery LA, van Schie CHM, Boulton AJM, Harkless LB. Off-loading the diabetic foot wound: A randomized clinical trial. Diabetes Care 2001; 24: 1019–22 [Google Scholar] |

| 23. | Boulton AJM. The diabetic foot: From art to science: The 18th Camillow Golgi lecture. Diabetologia 2004; 47: 1343–53. [Google Scholar] |

| 24. | Sibbald RG, Orsted H, Schultz GS, Coutts P, Keast D. Preparing the wound bed 2003: Focus on infection and inflammation. International Wound Bed Preparation Advisory Board; Canadian Chronic Wound Advisory Board. Ostomy Wound Manage 2003; 49: 24–51. [Google Scholar] |

| 25. | Dowsett C, Newton H. Wound bed preparations: TIME in practice. Wounds UK 2005; 1: 48–70. [Google Scholar] |

| 26. | Leaper DJ, Schultz G, Carville K, Fletcher J, Swanson T, Drake R. Extending the TIME concept: What have we learned in the past 10 years? Int Wound J 2012; 9 Suppl 2:1–19. [Google Scholar] |

| 27. | Frykberg RG. Charcot changes in the diabetic foot. In: Veves A, Giurini J, LoGerfo FW (eds). The diabetic foot: Medical and surgical management. Totowa, NJ:Humana Press; 2002:221–46. [Google Scholar] |

| 28. | Rogers LC, Frykberg RC, Armstrong DG, Boulton AJM, Edmonds M, Van GH, et al. The Charcot foot in diabetes. Diabetes Care 2011; 34: 2123–9. [Google Scholar] |

| 29. | Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes, 2014. American Diabetes Association. Position paper. Diabetes Care 2014; 37 (Suppl 1):S14–S80. [Google Scholar] |

| 30. | Hobizal KB, Wukich DK. Diabetic foot infections: Current concept review. Diabetic Foot Ankle 2012, 3. Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.3402/dfa.v3i0.18409 (accessed on 5 Dec 2014). [Google Scholar] |

| 31. | Lipsky BA. New developments in diagnosing and treating diabetic foot infections. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2008; 24 (Suppl 1):S66–71. [Google Scholar] |

| 32. | International Diabetes Federation, Clinical Guidelines Task Force. Global guideline for type 2 diabetes 2012;. Available at www.idf.org/sites/default/filesflDF%20T2DM %20Guideline.pdf (accessed on 5 Dec 2014). [Google Scholar] |

| 33. | Boulton AJ, Meneses P, Ennis WJ. Diabetic foot ulcers: A framework for prevention and care. Wound Repair Regen 1999; 7: 7–16. [Google Scholar] |

Fulltext Views

2,966

PDF downloads

1,828