Translate this page into:

Prevalence of premenstrual syndrome and its impact on quality of life among selected college students in Puducherry

Corresponding Author:

Balaji Bharadwaj

Department of Psychiatry, Jawaharlal Institute of Postgraduate Medical Education and Research Hospital, Dhanvantri Nagar, Puducherry 605006

India

balaji.b@jipmer.edu

| How to cite this article: Bhuvaneswari K, Rabindran P, Bharadwaj B. Prevalence of premenstrual syndrome and its impact on quality of life among selected college students in Puducherry. Natl Med J India 2019;32:17-19 |

Abstract

Background. Premenstrual syndrome (PMS) refers to a set of distressing symptoms experienced around the time of menstrual flow. Hormonal changes may underlie these symptoms which can lead to difficulties in day-to-day functioning and poor quality of life.Methods. In this cross-sectional study, 300 students attending the science stream at a women’s college of Puducherry were administered self-reported questionnaires to obtain socio- demographic, dietary, lifestyle and family details. The Shortened Premenstrual Assessment Form was used to assess PMS, a symptom checklist was used to assess premenstrual dysphoric disorder and Short From 36 was used to assess quality of life.

Results. The prevalence of PMS was 62.7%. Back, joint and muscle aches were the most common symptoms followed by abdominal heaviness and discomfort. PMS was associated with a poorer quality of life across all domains. About half the students had affective symptoms in the premenstrual phase.

Conclusion. Dietary and lifestyle factors such as consumption of sweets and lack of physical activity were associated with the presence of PMS.

Introduction

Premenstrual syndrome (PMS) is a set of distressing physical and psychological symptoms that begin a few days before menstruation and last for a few days after. This was first described by Frank and Horney in 1931.[1] Premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD) is a severe form of PMS and recurs for at least two menstrual cycles. PMDD has been included as a psychiatric disorder in the Fifth Edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders (DSM-5).

Previous Indian studies have found a 20% prevalence of PMS in the general population and among those with PMS 8% had severe symptoms.[2]·[3] Raval et al. did a study in Gujarat among 489 college students and found the prevalence of PMS was 18.4% and of PMDD was 3.7%.[4] In a study of medical students in Delhi, about 37% of participants had PMDD.[5]

Cheng et al. did a study among women university students to assess factors associated with PMS and found dietary factors such as consumption of fast food, drinks containing sugar, deep-fried foods and lifestyle factors such as less habitual exercise and poor sleep quality to be significantly associated with PMS.[6]

Women with PMS/PMDD have impairment in physical functioning, psychological health and also dysfunctions in occupational and social domains. Delara et al. assessed the quality of life among adolescents with and without PMDD, in which the physical role score in girls without PMDD was 74 and with PMDD was 52, and the emotional score in girls without PMDD was 70 and with PMDD was 44.[7] Therefore, there is a need to study the quality of life of women with PMS/PMDD.

We aimed to study the prevalence of PMS among students from a single college in Puducherry. We also assessed the quality of life of students with and without PMS, and analysed the dietary and lifestyle factors associated with PMS.

Methods

Following the approval by our institute ethics committee and permission from the department of education, we did a cross- sectional descriptive study among students of an arts and science women’s college in Puducherry.

Based on previous estimates of prevalence of PMS/PMDD among students which ranged from 8%[2] to 37%,[5] we expected a prevalence of about 25%. With a precision of 5% and 95% confidence interval, we required about 288 participants. To account for dropouts, we estimated a sample size of 300 and chose a single college by convenience for attaining this sample size.

Three hundred students above 18 years of age were selected from different sections of science streams. Consent was obtained after explaining the risk and benefits of the study.

The questionnaires were self-administered in a classroom with ample seating space to ensure privacy. The questionnaire was in English and all participants were educated in English medium and were able to understand the terms used in the questionnaire. The participants were allowed to ask any doubts or to clarify any terms, etc. However, none asked for any clarification.

Data collection was done in a single sitting using a self- administered questionnaire which consisted of four parts. The first part consisted of sociodemographic profile of the students, details of their menstrual cycle and lifestyle factors. The second part consisted of the Shortened Premenstrual Assessment Form (SPAF) developed by Allen et al.,s which is a 10-item tool validated for the assessment of PMS. We obtained permission to use the scale in our study. It has subscales, namely affect, water retention and pain. Each item is scored as: 1 no change; 2 minimal change; 3 mild change; 4 moderate change; 5 severe change; and 6 extreme change. The total scores were calculated and a score >27 was considered as PMS.[9] The third part consisted of a checklist based on DSM-5[10] criteria that had a list of symptoms for diagnosing PMDD. The participants were asked to mark the symptoms only if they had experienced it to be severe and debilitating for 1 week before the onset of the menstrual cycle for at least two menstrual cycles. Of the 11 symptoms, if the participant had at least 5 symptoms of which 1 symptom fell in the first 4 symptoms of the list and had disturbance in activities and decreased productivity, the participant was said to have PMDD. The final part consisted of a quality of life assessment using the Short Form- 36 Health Survey (SF-36),[11] which is available in the public domain. It has 8 sections including vitality, physical functioning, bodily pain, general health perceptions, physical role functioning, emotional role functioning, social role functioning and mental health. The scores range from 0 to 100, where lower score implies poorer functioning and quality of life.

Confounding variables such as age, department, residence, place of stay, family type, family income, age at menarche, duration of cycle, dysmenorrhoea and remedies to alleviate, family history of PMS/PMDD, physical activity, hours of sleep and dietary habits (caffeine consumption, salt intake, sweets and junk foods) were expressed as using frequency and percentages.

Physical activity was categorized as present or absent based on the presence of regular involvement in physical activities. Sleep was classified as per hours of sleep. Caffeine consumption could not be quantified and was classified as present or absent. Consumption of salt was rated as moderately high if the participant occasionally took pickles or added salt to the plate. It was rated as high if the participant routinely took extra salt or pickles. Intake of sweets and junk food was taken as present or absent.

Prevalence of PMS is reported as frequency or percentage. Quality of life among participants with and without PMS was summarized using mean and standard deviation. Association of confounding variables on premenstrual symptoms was done using the chi-square test. All statistical analyses were carried out at 5% level of significance and p<0.05 was considered statistically significant. The analyses were done using SPSS version 18 software package (IBM, Chicago, Illinois, USA).

Results

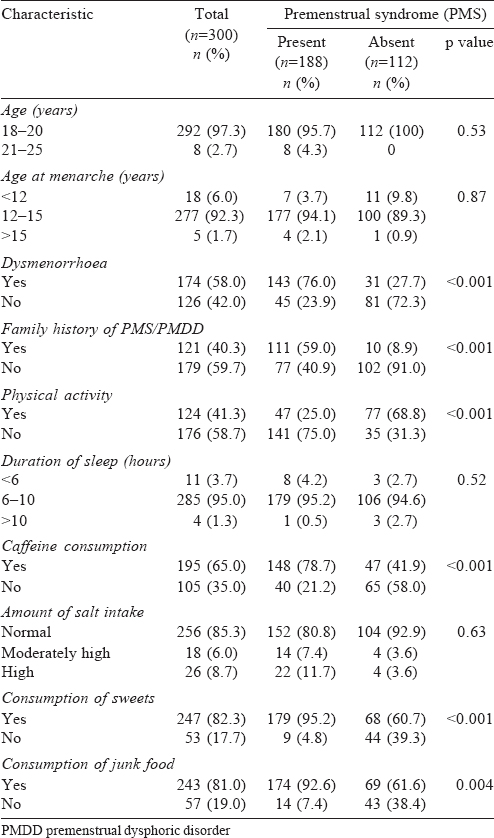

Three hundred students who participated in our study were between 18 and 22 years of age [Table - 1]. The participants were from four science stream departments including mathematics, computer science, physics and chemistry. A majority of them (73%) were from urban areas and belonged to a nuclear family (83.3%). The family income was between ₹10 001 and ₹50 000 per month among 142 (47.3%) of the participants.

The mean age at menarche was 13.6 (range 10-16) years. The mean (SD) duration of the cycle was 4.6 (1.07) days, 58% (174) had dysmenorrhoea and less than half of them (81) took some remedies for it. A family history of PMS/PMDD was present in 121 (40.3%) participants and 124 (41.3%) participants did regular physical activity. The mean (SD) duration of sleep among them was 7.56 (1.21) hours. A majority of participants (195 [65%]) drank coffee and 26 (8.7%) consumed a high amount of salt. About half the participants (46.2%) consumed sweets daily.

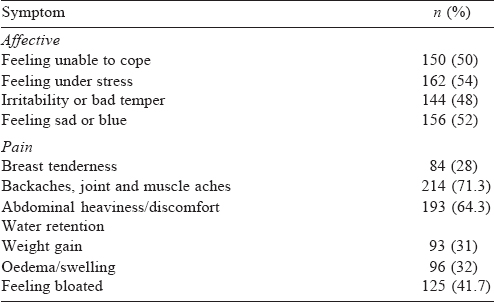

The most common premenstrual symptoms were body, muscle and joint aches (71.3%) followed by abdominal heaviness and discomfort (64.3%). About half of the respondents reported the affective domain symptoms of the SPAF questionnaire of moderate severity or worse [Table - 2].

We found that 188 of 300 (62.66%) participants had PMS using the defined score. Presence of dysmenorrhoea, a family history of PMS, indulging in physical activity, consumption of caffeine, consumption of high amount of salt, frequency and type of sweets and consumption of junk food were associated with PMS [Table - 1].

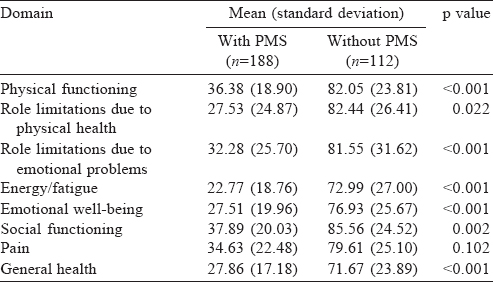

We studied the quality of life scores (SF-36) of participants with and without PMS [Table - 3]. The mean (SD) score of general health among participants without PMS was 71.7 (23.89) and that of participants with PMS was 27.9 (17.18).

As per the DSM-5 checklist, 197 (65.7%) had at least one item endorsed on the PMDD. Physical symptoms were most commonly endorsed by 70% of participants. The correlation coefficient between the SPAF score and PMDD checklist item count was r=0.748 (p<0.001). The common symptoms endorsed on the PMDD checklist included breast tenderness or swelling, headaches, joint or muscle pain, bloating or weight gain. Subjective sense of being overwhelmed or going out of control (25.7%) was the least common symptom.

Discussion

The prevalence of PMS was 62.7% among students of a women’s college attending courses of science stream. The estimate using the PMDD checklist in this group was 65.7%. This estimate of PMS/PMDD in our study is more than that in the study conducted among students (women) in a college of health sciences in Northern Ethiopia[12] in which the prevalence was 37%, and in the study conducted among medical students in New Delhi, the prevalence of PMDD was 3 7%.[5] However, it is similar to the study done in Al Qassim university among medical students, which showed a prevalence of 78.5%.[13] Our study being conducted in a women’s college, the participants may have been more forthcoming and willing to discuss their symptoms. We also found that the prevalence estimate of PMDD was paradoxically higher than that of PMS itself. This may be due to the use of DSM-5 criteria as a checklist for PMDD which is not an appropriate use of the instrument. Hence, we have done further analysis of association for PMS alone and not for PMDD. The high degree of correlation between the number of items endorsed on the PMDD checklist with the SPAF scores provides an additional validator of the high frequency of PMS in the study population.

The frequency of musculoskeletal aches and pains (71.3%), which is approximately similar to the studies conducted in Thrissur and Peshawar, was 73% and 77.3%, respectively.[1],[14] The second- most common symptom is abdominal heaviness, discomfort and pain (64.3%), which is similar to the Peshawar study (61.9%).[14]

We found a poor quality of life among students with PMS. This is similar to the study conducted in Al Qassim University among medical students, which also showed an association of PMS with physical problems, vitality, mental health and body pain, indicating decreased quality of life.[13]

Lifestyle factors such as physical activity, caffeine consumption and consumption of sweets and junk foods had a significant association with PMS. Mishra et al. also showed that lifestyle factors such as sleep, physical activity and total tea/coffee consumption were significantly associated with PMDD.[5] A study from Egypt revealed that 88.5% of students who had PMS had excess intake of sweet-tasting food items more than those (70.2%) who consumed less. It also showed that other factors such as intake of coffee and junk foods were significantly associated with PMS.[15] Thus, it is evident that lifestyle factors had a significant association with PMS and PMDD.

Limitations

We used DSM-5 criteria as a checklist for PMDD. The DSM-5 gives the diagnostic criteria for use in clinical practice. However, we have used it as a checklist for screening for PMDD because this was a community-based prevalence study. This has resulted in a false high estimate of PMDD. The family history of symptoms of PMS was self-reported by the participants and this is liable to bias or error as we have not independently confirmed it. We have not used stringent methods to measure high salt diet, physical activity and other lifestyle factors such as intake of sweets or junk food and these are based on self-reports of the participants.

Conclusion

We found a high prevalence of PMS (62.7%) among college students. The most common premenstrual symptoms were back, joint and muscle aches. Participants with PMS had poorer quality of life than those without PMS.

Acknowledgement

K. Bhuvaneswari was supported by the Golden-Jubilee Short Term Research Award for Undergraduate Students (GJ-STRAUS) scheme of Jawaharlal Institute of Postgraduate Medical Education and Research, Puducherry.

Conflicts of interest. None declared

| 1. | Joseph T, Nandini M, Sabira KA. Prevalence of premenstrual syndrome (PMS) among adolescent girls. JNurs Health Sci 2016;1:24-7. [Google Scholar] |

| 2. | Sarkar AP, Mandal R, Ghorai S. Premenstrual syndrome among adolescent girl students in a rural school of West Bengal, India. Int J Med Sci Public Health 2016;5:408-11. [Google Scholar] |

| 3. | Ziba T, Maryam S, Mohammad A. The effect of premenstrual syndrome on quality of life in adolescent girls. Iran J Psychiatry 2008;3:105-9. [Google Scholar] |

| 4. | Raval CM, Panchal BN, Tiwari DS, Vala AU, Bhatt RB. Prevalence of premenstrual syndrome and premenstrual dysphoric disorder among college students of Bhavnagar, Gujarat. Indian J Psychiatry 2016;58:164-70. [Google Scholar] |

| 5. | Mishra A, Banwari G, Yadav P. Premenstrual dysphoric disorder in medical students residing in hostel and its association with lifestyle factors. Ind Psychiatry J 2015;24:150-7. [Google Scholar] |

| 6. | Cheng SH, Shih CC, Yang YK, Chen KT, Chang YH, Yang YC, et al. Factors associated with premenstrual syndrome - A survey of new female university students. Kaohsiung J Med Sci 2013;29:100-5. [Google Scholar] |

| 7. | Delara M, Ghofranipour F, Azadfallah P, Tavafian SS, Kazemnejad A, Montazeri A, et al. Health related quality of life among adolescents with premenstrual disorders: A cross sectional study. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2012;10:1. [Google Scholar] |

| 8. | Allen SS, McBride CM, Pirie PL. The shortened premenstrual assessment form. J Reprod Med 1991;36:769-72. [Google Scholar] |

| 9. | Lee MH, Kim JW, Lee JH, Kim DM. The standardization of the shortened premenstrual assessment form and applicability on the internet. Korean Neuropsychiatry Assoc 2002;41:159-67. [Google Scholar] |

| 10. | American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Washington, DC:American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [Google Scholar] |

| 11. | Ware JE, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36), I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care 1992;12:102-6. [Google Scholar] |

| 12. | Tolossa FW, Bekele ML. Prevalence, impacts and medical managements of premenstrual syndrome among female students: Cross-sectional study in college of health sciences, Mekelle university, Mekelle, Northern Ethiopia. BMC Womens Health 2014;14:52. [Google Scholar] |

| 13. | Al-Batanony MA, Al-Nohair SF. Prevalence of premenstrual syndrome and its impact on quality of life among university medical students, Al Qassim university, KSA. Public Health Res 2014;4:1-6. [Google Scholar] |

| 14. | Tabassum S, Afridi B, Aman Z, Tabassum W, Durrani R. Premenstrual syndrome: Frequency and severity in young college girls. J Pak Med Assoc 2005;55:546-9. [Google Scholar] |

| 15. | Seedhom EA, Mohammed SE, Mahfouz EM. Life style factors associated with premenstrual syndrome among El-Minia university students, Egypt. ISRN Public Health 2013;2013:617123. [Google Scholar] |

Fulltext Views

12,345

PDF downloads

3,460