Translate this page into:

Scrub typhus: A prospective, observational study during an outbreak in Rajasthan, India

2 Department of Dermatology, Government Medical College, Kota, Rajasthan, India

3 Department of Conservative Dentistry and Endodontics, Jodhpur Dental College and General Hospital, Jodhpur, Rajasthan, India

4 Department of Internal Medicine, Government Medical College, Kota, Rajasthan, India

Corresponding Author:

Rajendra Prasad Takhar

Department of Respiratory Medicine, Government Medical College, Kota, Rajasthan

India

drrajtakhar@gmail.com

| How to cite this article: Takhar RP, Bunkar ML, Arya S, Mirdha N, Mohd A. Scrub typhus: A prospective, observational study during an outbreak in Rajasthan, India. Natl Med J India 2017;30:69-72 |

Abstract

Background. Scrub typhus, a potentially fatal rickettsial infection, is common in India. It usually presents with acute febrile illness along with multi-organ involvement caused by Orientia tsutsugamushi. As there was an outbreak of scrub typhus in the Hadoti region of Rajasthan and there is a paucity of data from this region, we studied this entity to describe the diverse epidemiological, clinico-radiological, laboratory parameters and outcome profile of patients with scrub typhus in a tertiary care hospital.Methods. In this descriptive study, we included all patients with an acute febrile illness diagnosed as scrub typhus by positive IgM antibodies against O. tsutsugamushi, over a period of 4 months (July to October 2014). All relevant data were recorded and analysed.

Results. A total of 66 (24 males/42 females) patients were enrolled. Fever was the most common presenting symptom (100%), and in 67% its duration was for 7–14 days. Other symptoms were breathlessness (66.7%), haemoptysis (63.6%), oliguria (51.5%) and altered mental status (39.4%). The pathognomonic features such as eschar (12%) and lymphadenopathy (18%) were not so common. The commonest radiological observation was consistent with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Complications noted were respiratory (69.7%), renal (51.5%) and hepatic dysfunction (48.5%). The overall mortality rate was 21.2%.

Conclusions. Scrub typhus has emerged as an important cause of febrile illness in the Hadoti region and can present with varying clinical manifestations with or without eschar. A high index of suspicion, early diagnosis and prompt intervention may help in reducing the mortality.

Introduction

Scrub typhus is a zoonotic infectious disease presenting with acute febrile illness of variable severity. Human beings get infected accidentally when they encroach upon mite-infested rural and suburban areas.[1] It is often acquired during recreational, occupational or agricultural exposure because crop fields are an important reservoir for transmission. It was considered a lethal disease in the pre-antibiotic era and continues to be a public health problem in South Asian and Western Pacific regions.[2]

In India, the first case of scrub typhus was reported in 2009 from Kerala.[3] Though widely prevalent in the Indian subcontinent, specific prevalence data are not available.[4] Apart from this, epidemics of scrub typhus have been reported from north, east and south India.[1] Due to lack of awareness, a low index of suspicion among clinicians, paucity of confirmatory diagnostic facilities and clinical symptoms mimicking other more prevalent diseases such as dengue, malaria and leptospirosis, scrub typhus is under- diagnosed in India, especially in Rajasthan.[5] The overall mortality varies from 7% to 30%, next only to malaria among infectious diseases.[6]

During an outbreak of acute febrile illness in the Hadoti region in the southern part of Rajasthan, investigations revealed the cause to be due to scrub typhus. Such an outbreak has not been reported earlier from this region. We studied the demographic, clinico-radiological and outcome of patients with scrub typhus during this outbreak.

Methods

We did this prospective, observational study at a tertiary care hospital in the Hadoti region of Rajasthan during an outbreak of scrub typhus from July to October 2014. All clinically suspected patients with an acute febrile illness (in whom malaria, leptospirosis, dengue fever, viral pharyngitis, enteric fever and urinary tract infection were excluded by history, clinical examination and appropriate laboratory investigations) were included in this study. All demographic data, detailed history, past treatment history/any comorbid illnesses were recorded in a proforma. A complete physical examination, vital signs and relevant investigations were also noted.

All patients were subjected to investigations to establish the cause of fever. These included a peripheral blood smear for malarial parasites, complete blood count, serology for dengue, leptospirosis, scrub typhus, enteric fever and retroviral infections; blood, urine, sputum and/or endotracheal cultures and a smear for acid-fact bacilli using the Ziehl–Neelson's method. A Mantoux test, X-ray chest, ultrasound abdomen, contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CECT) scan of the thorax and abdomen were ordered as and when required. A CT of the brain and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis were done, if clinically indicated. Biochemical investigations including fasting blood sugar, renal function and liver function tests were done and recorded.

Scrub typhus serology was tested in batches for IgM antibodies to Orientia tsutsugamushi using commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits (Panbio Ltd, Brisbane, Australia). The kit uses a specific 56 kDa recombinant antigen of O. tsutsugamushi and has a sensitivity and specificity of >90% when compared with recommended gold standard tests, namely the immunofluorescent antibody (IFA) and indirect immuno- peroxidase tests. The test was performed as per manufacturer's instructions. The study protocol was approved by the institutional ethics committee and informed consent was obtained from the patients. A diagnosis of scrub typhus was confirmed when a patient with an AFI had a positive serology for scrub typhus, further strengthened by either the presence of eschar or exclusion of other causes of fever.

Initially, all patients with AFI were treated with empirical antibiotics (intravenous pipericillin–tazobactam and azithromycin) and symptomatic treatment. After confirmation of the diagnosis of scrub typhus, piperacilli–tazobactam was stopped and doxycycline 200 mg per day was started while azithromycin was continued for 7–10 days.

Patients with multi-organ dysfunction (e.g. acute respiratory distress syndrome [ARDS] with or without shock, renal failure, elevated transaminase levels, leucocytosis and thrombocytopenia) were managed with organ support measures as appropriate such as invasive or non-invasive ventilation, inotropic support, renal replacement therapy and blood and blood products.

The presence of organ dysfunction at the time of hospitalization was assessed by using the sequential organ failure assessment (SOFA) score. Organ dysfunction was said to be present if the organ-specific SOFA score was >1 and organ failure if the SOFA score was >3.[7]

Outcome measures

The primary outcome was in-hospital mortality and the secondary outcomes included length of stay in the intensive care unit (ICU) and hospital, the need for and duration of mechanical ventilation, type of ventilatory support (invasive or non-invasive) and need for dialysis.

Results

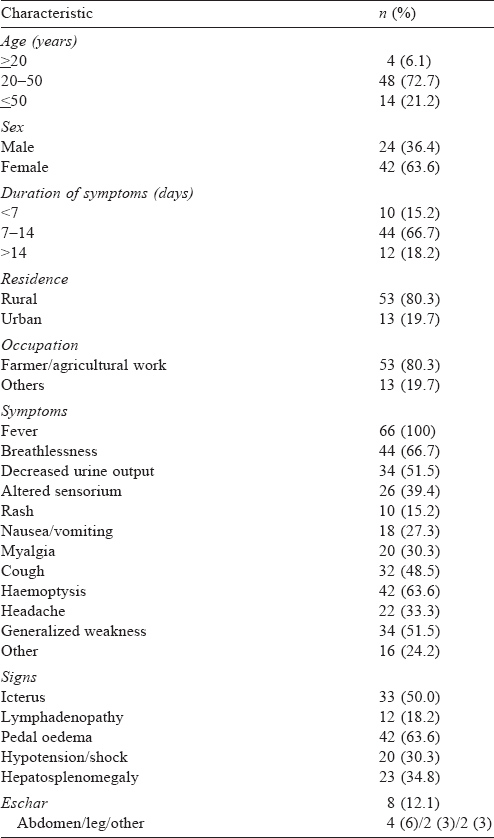

During the study period, 290 patients were admitted to our hospital with AFI. Of these 66 (22.8%) patients (24 males and 42 females) were diagnosed to have scrub typhus [Table - 1]. Fever was the commonest presenting symptom followed by haemoptysis and cough. The common clinical signs were pedal oedema, jaundice and hepatosplenomegaly. Eschar (8 patients) and lymphadenopathy (12 patients) were seen less commonly.

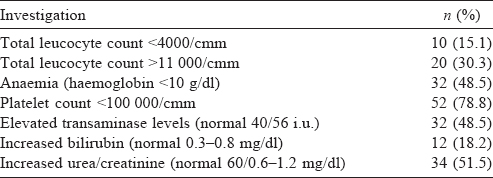

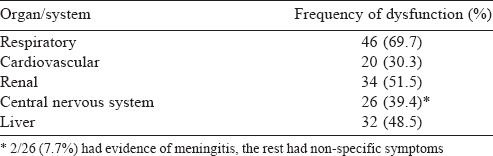

Low platelet counts and abnormal renal functions were frequently abnormal [Table - 2]. Nearly half our patients (48.5%) had involvement of three or more organ systems. Respiratory dysfunction was the commonest (46; 69.7%), followed by renal (51.5%) and hepatic dysfunction (48.5%). Twenty patients (30.3%) had dysfunction of all five organ systems during the course of hospitalization [Table - 3]. Among the 46 patients with respiratory dysfunction, ARDS (34, 73.9%) was the commonest, followed by pleural effusion (30, 65.2%) and pulmonary infiltrates on chest X-ray (12, 26.1%).

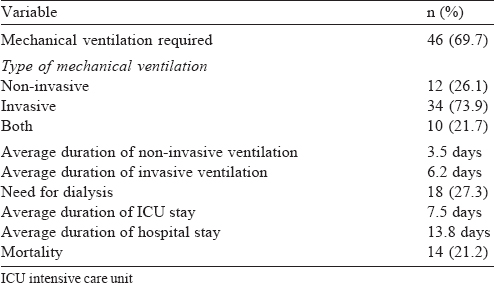

Forty-six of the patients required ventilation [Table - 4], 18 required dialysis and the overall mortality was 14 (21.2%).

Discussion

Scrub typhus is a potentially fatal infection that affects about one million people every year worldwide.[8] It is a common cause of multi-organ dysfunction and an important cause of admission in ICUs of patients with AFI.

Rickettsial infections have been documented from various parts of India.[9] There have been reports of sporadic outbreaks of scrub typhus mainly in the eastern and southern Indian states with serological evidence of widespread prevalence of spotted fevers and scrub typhus,[10],[11] particularly during the monsoon and post- monsoon months.[1],[11],[12],[13] The outbreak that we studied also occurred during the same period.

During our study, 22.8% (66/290) of patients with AFI presenting to us had scrub typhus, an observation (24.7%) similar to the study from an adjoining region by Sinha et al.[14]

Age, sex, residential area and occupation are known to influence the occurrence of scrub typhus. People working outdoors tend to be afflicted more often. Most of our patients were 20–50 years of age, an observation similar to Sinha et al.[14] and Madi et al.[15] However, while more women were affected in our series, Rajoor et al. reported more men to be affected.[4] This could probably be because men in the Hadoti region tend to migrate to cities for work and women look after the agricultural work.

The clinical manifestations of this disease vary from minimal disease to severe fatal illness with multi-organ dysfunction. Our patients too presented with similar clinical manifestations and these have been reported in another study from the Indian subcontinent.[16]

We considered the duration of symptoms from the time of onset of fever as this was the first symptom in most patients. Two- thirds of the patients were diagnosed in the second week and had manifestations akin to those reported in previous studies.[1],[14],[15],[17]

Eschar at the site of attachment of the larval mite/chigger is considered highly suggestive of scrub typhus, but occurs in a variable proportion of patients in different studies.[18] It is a blackish necrotic lesion resembling a cigarette burn generally found in areas where the skin is thin, moist or wrinkled, and where the clothing is tight such as over the abdomen, groin and on the legs.[4] Its presence is considered pathognomonic of the disease but its absence does not exclude the possibility of scrub typhus. However, it is relatively difficult to detect on dark-skinned patients.[19] In our study, eschar was present in 8 (12.1%) patients and the most common site was the lower abdomen. While similar rates (4%–12%) have been reported by some Indian studies,[4],[9],[12] Vivekanandan et al.[1] (46%), Chrispal et al.[16] (45.5%) and studies from Vietnam,[20] Taiwan,[21] and Korea[22] reported slightly higher incidences of eschar probably due to fair-skinned population of these studies, which increases the chances of finding eschar.

Premaratna et al. also postulated that in dark-skinned patients early/very small eschar could be easily overlooked.[10] This difference in incidence of eschar may also be due to variation in serotypes/ endemic strain among the regions.[1],[14],[23] One study found that not a single patient presented with eschar.[14] Our findings were similar to those by Razak et al. who concluded that the occurrence of eschar is less frequent among patients from Southeast Asia.[17] Studies have also found a significant difference in the gender distribution of eschars, but the gender distribution was not significantly different in our study.[24]

Eschar is more often than not associated with regional lymphadenopathy. Only 18% of our patients had lymphadenopathy. A wide range (22%–53%) of lymphadenopathy has been reported in different studies.[1],[4],[9],[14] and some have suggested that the presence of generalized lymphadenopathy suggests a late presentation and a worse outcome.[9]

The abnormalities in cell counts, and liver and renal functions in our patients were consistent with those reported in other studies. [1],[4],[12],[15]

Among our patients who presented with any central nervous system manifestations, 26 required CSF examination and only 2 had confirmed meningitis. However, Viswanathan et al. had 17 patients with meningitis among 65 of their patients.[25] This is possibly because they specifically searched for patients with scrub typhus and meningitis. Scrub typhus should be considered in the differential diagnosis of ‘subacute’ meningitis, especially when accompanied by renal failure or jaundice.[26] Previous studies from India have reported meningoencephalitis in 9.5%–23.3% of patients.[1],[11],[13]

Scrub typhus is a cause of multi-organ dysfunction. Nearly half of our patients (48.5%) had three or more organ systems involved while 20 patients (30%) had evidence of dysfunction of five organs during the course of their hospital stay. Complications in scrub typhus develop after the first week of illness. Narvencar et al. found hepatic dysfunction to be the most common followed by ARDS, circulatory collapse and acute renal failure.[27] We found respiratory dysfunction in over two-thirds of patients, followed by renal dysfunction in over half the patients.

As the main organ dysfunction in our study was respiratory failure, 46 of our patients (69.7%) required mechanical ventilation. Of these, 12 were managed with only non-invasive ventilation, 10 required non-invasive ventilation to be changed to invasive mechanical ventilation and 34 patients were managed at the outset with invasive mechanical ventilation. A study from southern India also showed involvement of the respiratory system in 76.9% of patients and requirement of ventilatory support in 68.9% of patients.[11]

The mortality in patients with scrub typhus has wide variations and depends on the circulatory load of O. tsutsugamushi, early or late presentation and treatment modality. Deaths are attributable to delayed presentation or diagnosis, and drug resistance. Complications such as ARDS, renal failure and hepatic involvement are independent predictors of mortality; most of these were present in our patients.[28]

The case fatality rate for scrub typhus has been 7%–30%,[29] including 10% in Korea[23] to 30% in Taiwan.[30] The mortality rate of 21.2% in our study was slightly higher compared to other studies from India by Mahajan et al. (mortality 14.2%),[13] Kumar et al. (mortality 17.2%)[31] and Rungta et al.[32] while somewhat low as compared to that reported by Lai et al. (mortality 15%–30%)[30] and Griffith et al.[33] Studies have shown inter-strain variability in virulence[23] and since we did not do serotyping and genotyping, it is possible that the strain type present in our region was a more virulent one causing higher case fatality.

The main strength of our study is that we included confirmed cases of scrub typhus who had IgM antibodies against O. tsutsugamushi.

Diagnosis of scrub typhus is difficult in India because of its varied clinical presentation, absence of eschar in many patients, and lack of availability of specific tests (ELISA/serological tests). In developing countries with limited resources such as India, we suggest that the diagnosis of scrub typhus should be based largely on a high index of suspicion and careful clinical, laboratory and epidemiological evaluation. It is prudent to recommend empirical antibiotic therapy in patients with acute febrile illness with evidence of multi-organ involvement.

Conclusion

Scrub typhus is prevalent in many states of southern and eastern India, but outbreaks have been occurring in other parts too, including in Rajasthan. Mortality in these patients is most often due to multi-organ dysfunction.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the healthcare staff involved in the care of our patients.

| 1. | Vivekanandan M, Mani A, Priya YS, Singh AP, Jayakumar S, Purty S. Outbreak of scrub typhus in Pondicherry. J Assoc Physicians India 2010; 58: 24–8. [Google Scholar] |

| 2. | Kweon SS, Choi JS, Lim HS, Kim JR, Kim KY, Ryu SY, et al. Rapid increase of scrub typhus, South Korea, 2001–2006. Emerg Infect Dis 2009; 15: 1127–9 [Google Scholar] |

| 3. | Ittyachen AM. Emerging infections in Kerala: A case of scrub typhus. Natl Med J India 2009; 22: 333–4. [Google Scholar] |

| 4. | Rajoor UG, Gundikeri SK, Sindhur JC, Dhananjaya M. Scrub typhus in adults in a teaching hospital in north Karnataka, 2011–2012. Ann Trop Med Public Health 2013; 6: 614–17. [Google Scholar] |

| 5. | Isaac R, Varghese GM, Mathai E, Manjula J, Joseph I. Scrub typhus: Prevalence and diagnostic issues in rural southern India. Clin Infect Dis 2004; 39: 1395–6. [Google Scholar] |

| 6. | Mahajan SK, Bakshi D. Acute reversible hearing loss in scrub typhus. J Assoc Physicians India 2007; 55: 512–14. [Google Scholar] |

| 7. | Vincent JL, Moreno R, Takala J, Willatts S, De Mendonça A, Bruining H, et al. The SOFA (Sepsis-related Organ Failure Assessment) score to describe organ dysfunction/ failure. On behalf of the Working Group on Sepsis-Related Problems of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine. Intensive Care Med 1996; 22: 707–10. [Google Scholar] |

| 8. | Watt G, Parola P. Scrub typhus and tropical rickettsioses. Curr Opin Infect Dis 2003; 16: 429–36. [Google Scholar] |

| 9. | Mahajan SK, Kashyap R, Kanga A, Sharma V, Prasher BS, Pal LS. Relevance of Weil-Felix test in diagnosis of scrub typhus in India. J Assoc Physicians India 2006; 54: 619–21. [Google Scholar] |

| 10. | Premaratna R, Chandrasena TG, Dassayake AS, Loftis AD, Dasch GA, de Silva HJ. Acute hearing loss due to scrub typhus: Forgotten complication of a re-emerging disease. Clin Infect Dis 2006; 42: e6–e8. [Google Scholar] |

| 11. | Varghese GM, Abraham OC, Mathai D, Thomas K, Aaron R, Kavitha ML, et al. Scrub typhus among hospitalised patients with febrile illness in South India: Magnitude and clinical predictors. J Infect 2006; 52: 56–60. [Google Scholar] |

| 12. | Mathai E, Rolain JM, Verghese GM, Abraham OC, Mathai D, Mathai M, et al. Outbreak of scrub typhus in southern India during the cooler months. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2003; 990: 359–64. [Google Scholar] |

| 13. | Mahajan SK, Rolain JM, Kashyap R, Bakshi D, Sharma V, Prasher BS, et al. Scrub typhus in Himalayas. Emerg Infect Dis 2006; 12: 1590–2. [Google Scholar] |

| 14. | Sinha P, Gupta S, Dawra R, Rijhawan P. Recent outbreak of scrub typhus in north western part of India. Indian J Med Microbiol 2014; 32: 247–50. [Google Scholar] |

| 15. | Madi D, Achappa B, Chakrapani M, Pavan MR, Narayanan S, Yadlapati S, et al. Scrub typhus, a reemerging zoonosis—an Indian case series. Asian J Med Sci 2014; 5: 108–11. [Google Scholar] |

| 16. | Chrispal A, Boorugu H, Gopinath KG, Prakash JA, Chandy S, Abraham OC, et al. Scrub typhus: An unrecognized threat in South India—clinical profile and predictors of mortality. Trop Doct 2010; 40: 129–33. [Google Scholar] |

| 17. | Razak A, Sathyanarayanan V, Prabhu M, Sangar M, Balasubramanian R. Scrub typhus in southern India: Are we doing enough? Trop Doct 2010; 40: 149–51. [Google Scholar] |

| 18. | Chogle AR. Diagnosis and treatment of scrub typhus—the Indian scenario. J Assoc Physicians India 2010; 58: 11–12. [Google Scholar] |

| 19. | Kim DM, Won KJ, Park CY, Yu KD, Kim HS, Yang TY, et al. Distribution of eschars on the body of scrub typhus patients: A prospective study. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2007; 76: 806–9. [Google Scholar] |

| 20. | Berman SJ, Kundin WD. Scrub typhus in South Vietnam: A study of 87 cases. Ann Intern Med 1973; 79: 26–30. [Google Scholar] |

| 21. | Tsay RW, Chang FY. Serious complications in scrub typhus. J Microbiol Immunol Infect 1998; 31: 240–4. [Google Scholar] |

| 22. | Kim DM, Kim SW, Choi SH, Yun NR. Clinical and laboratory findings associated with severe scrub typhus. BMC Infect Dis 2010; 10: 108. [Google Scholar] |

| 23. | Chang WH. Current status of tsutsugamushi disease in Korea. J Korean Med Sci 1995; 10: 227–38. [Google Scholar] |

| 24. | Kundavaram AP, Jonathan AJ, Nathaniel SD, Varghese GM. Eschar in scrub typhus: A valuable clue to the diagnosis. J Postgrad Med 2013; 59: 177–8. [Google Scholar] |

| 25. | Viswanathan S, Muthu V, Iqbal N, Remalayam B, George T. Scrub typhus meningitis in South India—a retrospective study. PLoS One 2013; 8: e66595. [Google Scholar] |

| 26. | Mathew A, Verghese GM, Kumar S et al. Diagnosing meningoencephalitis due to scrub typhus using clinical and laboratory features. J Assoc Physician India 2005; 53: 259. [Google Scholar] |

| 27. | Narvencar KP, Rodrigues S, Nevrekar RP, Dias L, Dias A, Vaz M, et al. Scrub typhus in patients reporting with acute febrile illness at a tertiary health care institution in Goa. Indian J Med Res 2012; 136: 1020–4. [Google Scholar] |

| 28. | Varghese GM, Trowbridge P, Janardhanan J, Thomas K, Peter JV, Mathews P, et al. Clinical profile and improving mortality trend of scrub typhus in south India. Int J Infect Dis 2014; 23: 39–43. [Google Scholar] |

| 29. | Pandey D, Sharma B, Chauhan V, Mokta J, Verma B S, Thakur S. ARDS complicating scrub typhus in sub-Himalayan region. J Assoc Physicians India 2006; 54: 812–13. [Google Scholar] |

| 30. | Lai CH, Huang CK, Weng HC, Chung HC, Liang SH, Lin JN, et al. The difference in clinical characteristics between acute Q fever and scrub typhus in southern Taiwan. Int J Infect Dis 2009; 13: 387–93. [Google Scholar] |

| 31. | Kumar K, Saxena VK, Thomas TG, Lal S. Outbreak investigation of scrub typhus in Himachal Pradesh (India). J Commun Dis 2004; 36: 277–83. [Google Scholar] |

| 32. | Rungta N. Scrub typhus: Emerging cause of multiorgan dysfunction. Indian J Crit Care Med 2014; 18: 489–91. [Google Scholar] |

| 33. | Griffith M, Peter JV, Karthik G, Ramakrishna K, Prakash JA, Kalki RC, et al. Profile of organ dysfunction and predictors of mortality in severe scrub typhus infection requiring intensive care admission. Indian J Crit Care Med 2014; 18: 497–502. [Google Scholar] |

Fulltext Views

4,350

PDF downloads

2,738