Translate this page into:

Secondary hospital rotation of postgraduate trainees: A pilot study

Corresponding Author:

Punitha Victor

Department of Medicine, Christian Medical College, Vellore 632004, Tamil Nadu

India

puniljcak@yahoo.co.uk

| How to cite this article: Victor P, Chandy G, George K, Zachariah A. Secondary hospital rotation of postgraduate trainees: A pilot study. Natl Med J India 2019;32:303-307 |

Abstract

Background. Postgraduate (PG) training in general medicine requires reorientation to meet the healthcare needs of India. In this pilot study, we designed a secondary hospital (SH) posting for medicine PGs to sensitize them to the practice of medicine and challenges in a rural SH setting.Methods. PG trainees in general medicine were sent for a 2-week rotation to select SHs. A faculty coordinator from the teaching hospital facilitated the programme. The SH faculty used qualitative tools to assess the performance of the trainees. The trainees also evaluated the programme using open- and close-ended questionnaires.

Results: Eighteen PG trainees in general medicine were posted to six rural SHs. Data analysis showed that the training exposure provided sensitization to the challenges of medical practice in such settings and the need to be multicompetent. Seventeen (94%) trainees felt that they gained insight into the issues that are specific for practice at an SH and >80% expressed confidence about the knowledge and skills gained during that exposure to enhance medical practice in a resource-limited setting. They were also sensitized to various issues of secondary care including skills of multi-competence, the ability to handle a wide variety of cases with limited investigations, a cost-effective approach, decision-making on referrals, procedural competence and flexibility to adapt to new situations.

Conclusion. A short SH posting can positively sensitize PGs to the practice of medicine and challenges in secondary care settings.

Introduction

Medical education in India has grappled to make training relevant to societal needs. Both the graduate and postgraduate (PG) training occurs exclusively in a tertiary care setting. The learners are far removed from the realities in which they are expected to practise medicine, which is either a primary or secondary hospital (SH), in a rural rather than an urban setting. Disparity in the distribution of doctors between rural and urban areas has been reported due to a myriad of reasons.[1] However, nearly 70% of India is rural,[2] where both medical services and doctors are either lacking or grossly inadequate.[1] One of the important factors is a deficit of 81% in the number of broad specialists (physicians, surgeons, obstetricians, gynaecologists and paediatricians) at the secondary level in district hospitals, taluk hospitals and community health centres.[3]

Various efforts have been made to reorient medical education to the healthcare needs of the society, ensuring equity focused on undergraduate training. Several medical colleges in India have pioneered in community-oriented medical education, such as the Christian Medical College, Vellore and Ludhiana, and St John’s Medical College and Mahatma Gandhi Institute of Medical Sciences, Sewagram, Maharashtra, India.[4],[5] Several efforts have been made in the USA and the UK to shift PG training to community hospitals.[6],[7] In fact, in the UK, the majority of PG training in the national health system occurs in community hospitals. The call for this pedagogic shift to contextualize PG medical training in India is new, and requires commitment and innovation to overcome the resistance that accompanies such changes.

The Christian Medical College, Vellore, is linked to over 200 secondary care hospitals (SHs) in rural and remote parts of the country. These hospitals provide broad-based secondary and primary care to local communities. PG alumni already working in rural SHs encountered challenges in trying to adapt to these settings such as the undifferentiated nature of medical problems, limited laboratory facilities, referral supports and social and academic isolation.

The PG SH programme was developed in response to these felt needs. It was felt that such an exposure might develop an interest in them and influence their career choice. The aim of this programme was to sensitize PG trainees in general medicine to the needs and challenges of rural secondary care and the practice of medicine in SH settings. We report our experience of introducing a short rotation to a few SHs for general medicine PGs during their MD training.

Methods

Structure of the posting

PG trainees in general medicine during their second year of training were sent for a 2-week residential posting to select SHs. These are academically oriented rural/semi-urban SHs with adequate case-load and basic laboratory facilities, and a PG teacher who is willing to supervise the trainee posted there. The students were integrated into the SH medical team and took up responsibilities to manage inpatients, outpatients, intensive care patients and emergencies. They maintained a log book of the list of cases they managed and procedures performed at the SH.

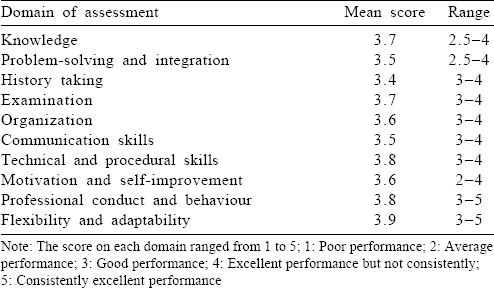

Student assessment

A work-based performance assessment of the trainees was provided by the SH faculty at the end of 2 weeks. This assessment tool has 10 different domains [Table - 1]. Each domain has a score ranging from 1 to 5 (1 very poor to 5 consistently excellent). An open-ended qualitative feedback was provided by the SH faculty for each student.

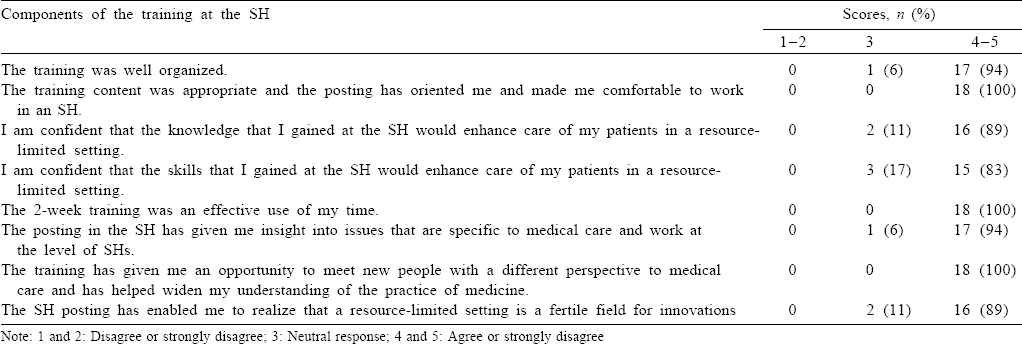

Programme evaluation

An open- and close-ended questionnaire was used for programme evaluation. The closed questionnaire used a Likert scale with scores 1–5 (1 and 2: disagreed with the statement; 3: neutral response; and 4 and 5: agreed with the statement).

Analysis

The responses of the SH faculty members to close- and open- ended questionnaires on the trainees were analysed. Similarly, the responses of the trainees to close- and open-ended questionnaires about the programme were analysed. The details of the qualitative analysis are provided below. The closed questionnaire results are presented as a simple percentage of those who agreed, disagreed or remained neutral on each statement. The analysis of the assessment of the trainees by the SH faculty is presented as a mean score on each domain.

Qualitative analysis by triangulation[8] was done. Data from multiple sources, namely responses from open-ended questionnaires, reflective writings, documented case reports and PowerPoint presentations were taken, and an inductive content analysis was done. The data were compiled, coded and then clustered together under emerging themes. The data were analysed independently by two persons, which were then discussed and the converging themes were reported in the final analysis. This was then subjected to a process of ‘member checking’[8] in which the PG trainees and the SH faculty were asked to comment on the validity of the emergent themes—whether it synchronized with the reality of their experience. These processes were included to improve the robustness of the data and to prevent bias.

Results

Eighteen PG trainees were posted to six SHs between 2014 and 2016 for a period of 2 weeks.

Performance of the trainees

Most trainees had performed adequately, scoring 3 on all the domains [Table - 1]. A mean score of 3.4 to 3.7 is observed in domains pertaining to the clinical approach and communication skills. A mean score of 3.5 was observed on motivation and self-improvement. This indicates that the trainees had a good initiative, were able to respond to criticism and identify and correct deficiencies in themselves.

Evaluation of the programme by PGs

Seventeen (94%) PGs felt that they gained insight into issues specific for practice at the SH and >80% expressed confidence about knowledge and skills gained to enhance medical practice in a resource-limited setting [Table - 2].

Major themes on inductive analysis

The significant themes that emerged from the SH faculty feedback to students regarding their performance were as follows:

- Need for clinical approach to patient: complete history and examination

- Ordering necessary tests to clinch the diagnosis

- Managing a wider spectrum of cases

- Referral only when necessary, keeping in mind the cost issues and travel distance

- Importance of communication skills

- Need to practise cost-effective medicine

The faculty felt that PG students contributed to mutual learning that improved patient care.

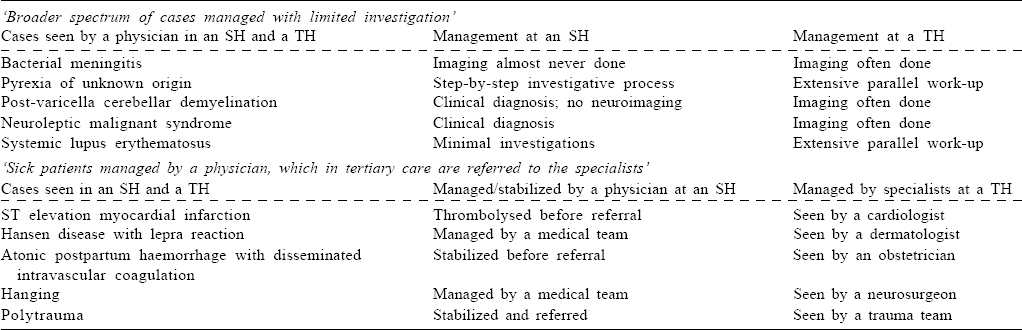

[Table - 3] provides a more exhaustive list of themes that emerged from the trainees.

A clinical approach to diagnosis

All trainees commented on the importance of being an astute clinician. One student captured this as follows, ‘the posting has helped me look at each case with keener ears and sharper eyes!' Another trainee reported a patient with cyanosis who did not improve with supplemental oxygen. He was diagnosed to have methaemoglobinaemia based on a chocolate brown blood colour. The patient improved on treatment and the diagnosis was later confirmed biochemically. Trainees learnt that clinical judgement was critical in the immediate management of patients since investigations were either delayed or not available.

Clinically oriented teaching by the SH faculty

This theme consistently appeared in the feedback and case write-ups. One trainee said: ‘the teaching rounds provided a positive impetus for me to work-up the cases in detail and discuss them based mostly on clinical findings and minimal investigations’.

Management with limited resources

The trainees quickly realized the limitations with regard to finances, laboratory facilities and treatment options. This heightened their sensitivity towards a cost-effective clinical approach. One student wrote, '…resources were greatly limited. (this) made me pause to think before ordering any investigation and consider if it was really needed or could be supplanted by clinical probability. Selective ordering of investigations rather than ordering indiscriminately… Certainly boosted my confidence in guiding decisions with clinical findings.'

Multicompetence and broad-based preparedness

One other challenge expressed was the ability to tackle any problem presented to them—medical or otherwise! They had to manage a wider spectrum of cases; the need for them to be a generalist and to be multicompetent was another theme that emerged. One trainee wrote, ‘needed to see patients from broader specialties due to lack of specialty departments’. They were also required to take complete medical, financial and legal responsibilities of the situation.

They also mentioned on how the SH faculty were equipped with additional skills such as performing echocardiography, treadmill test, ultrasound, gastroscopy and pericardiocentesis. This was crucial for diagnosis and also in saving lives.

Innovations in practice

A number of innovations were observed to minimize costs, compensate for lack of specialists or make services efficient.

Decision-making on referral to higher centres

The trainees developed insights into the approach of referral of cases to a higher centre. Referral was a complex issue because of patient preference, cost, patient safety and medicolegal issues. For instance, in one hospital once an electrocardiogram shows ST elevation, it is sent to the nearest cardiac centre online and if the cardiologist feels percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty has to be done, the patient is sent in an ambulance. One trainee wrote: ‘Risk stratification enables management… in the low-cost setting itself without need for referral (which) would reduce the risk of transport of a sick patient. and… reduce cost of care by 3–4 times.'

Career orientation

Trainees realized the potential for future work in a secondary care setting: ‘These 2 weeks have made me realize that a well-functioning SH can provide useful, appropriate medical care to a large section of the community and could be a viable career option in the future.'

Analysis of log books showed that most of the cases managed by the trainees were similar to the cases seen at a tertiary care centre except with regard to the complexity and the investigative process. All the trainees highlighted that the major difference was the management of a broader spectrum of cases in the SH and the stabilization of sick patients that would never be seen by a physician in a tertiary care centre since they are invariably referred to specialists [Table - 4].

All the procedures that are usually done in a tertiary care setting are also done at an SH and trainees are given opportunities to perform them during their SH postings. Gastroscopy, echo-cardiography, ultrasound, treadmill test and pericardiocentesis that are invariably done by a specialist in a tertiary care centre were being done by the secondary care physician in these SHs.

Discussion

The purpose of posting PG trainees to an SH was to sensitize them to the challenges and practice of medicine at secondary care hospitals.

The students learnt how the practice of medicine was different at the secondary level by working alongside SH physicians who were excellent role models. The work-based assessments showed that the students performed well during their SH posting. In addition to being sensitized to the issues in secondary-care hospitals, they developed a positive orientation towards them.

The observations in our study are consistent with our current understanding of PG education involving ‘situated learning’ by increasing immersion in practice.[9] An SH offers a different context for situated learning with regard to the types of cases, the facilities, tests and referral facilities available, cost constraints and a much higher level of responsibility. They learn from role models (teachers) who are experienced practitioners of secondary care medicine. They learn the ‘tacit knowledge’ of secondary care practice within the specificities of the local context.[10]

Postgraduate training in Canada emphasizes the concept of generalism to meet healthcare needs in the community. ‘Generalism is a philosophy of care with acknowledgement by the physician that broad-based comprehensive care is provided and the generalist physician is prepared and willing to reach across the existing gaps in the healthcare delivery system.‘[11] In the latest report of the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada, it has been recommended that ‘residents must be exposed to generalist practitioners within their discipline, rather than simply moving from one highly subspecialized rotation to another. Furthermore, it is critical that our programmes offer learning experiences outside of the large, urban tertiary and quaternary care facilities, to expose trainees to a variety of practice settings’.[12]

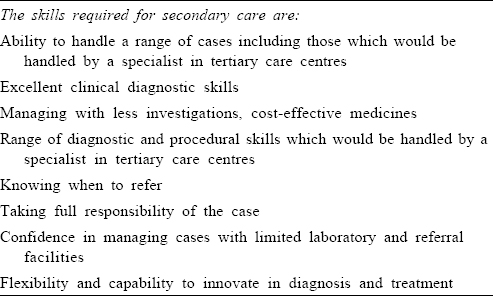

The training exposure was short and served to provide sensitization by providing a better understanding of the community and societal needs, promoted need-based learning and boosted the confidence of a PG trainee to work in secondary-level hospitals. We believe that this model of training aligns with the country’s needs and the competence-based learning objectives stated by the Medical Council of India in 2000. Based on our study, we suggest that competencies for PG SH training in general medicine [Table - 5] be included in a PG secondary care curriculum.

The merits of the SH posting are the learning of secondary care medicine, improving clinical skills, increased motivation of the students and exposure to role models (teachers) and sensitization to healthcare needs. Since the concept of SH postings is new in medical colleges, this requires a buy-in from the teachers and their help in planning postings to ensure staffing of the clinical service.

The need of the hour, therefore, is to intentionally plan and incorporate SH postings as part of the PG training curriculum. Jacob emphasized the urgent need to ‘relocate medical education away from tertiary settings and situate it in secondary and primary settings’[13] since this would help address the health needs of the country. More studies and experiences pertaining to contextualized SH PG training exposures from both the government and private sectors in different regions of India would need to be conducted and analysed before a consensus model could be developed for the country.

Limitations

The main limitation is that our’s is a small pilot study. Another limitation is the use of a non-validated tool for assessing student performance in various domains.

Future directions

We hope that every medical school in India would take a small step towards ‘providing appropriate opportunities for our PG trainees to be exposed to the health needs in the country’.[14] If every medical school could adopt a community and make it central to medical training, it would greatly help India achieve equity in health.

Conflicts of interest. None declared

| 1. | Bajpai V. The challenges confronting public hospitals in India, their origins, and possible solutions. Adv Public Health 2014. Available at www.hindawi.com/ journals/aph/2014/898502/ (accessed on 4 Sep 2017). [Google Scholar] |

| 2. | Census of India 2011. Rural urban distribution of population. Available at www.censusindia.gov.in/2011-prov-esults/paper2/data_files/india/ Rural_Urban_2011.pdf (accessed on 4 Sep 2017). [Google Scholar] |

| 3. | State-wise/UT-wise allopathic doctors at primary health centres for 2005 and 2016. Available at www.nrhm-mis-nic.in/Pages/RHS2016.aspx (accessed on 4 Sep 2017). [Google Scholar] |

| 4. | Sankarapandian V, Christopher PR. Family medicine in undergraduate medical education in India. J Family Med Prim Care 2014;3:300-4. [Google Scholar] |

| 5. | Krishnan A, Misra P, Rai SK, Gupta SK, Pandav CS. Teaching community medicine to medical undergraduates—learning by doing: Our experience of rural posting at All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi, India. Natl Med J India 2014;27:152-8. [Google Scholar] |

| 6. | Lee SW, Clement N, Tang N, Atiomo W. The current provision of community-based teaching in UK medical schools: An online survey and systematic review. BMJ Open 2014;4:e005696. [Google Scholar] |

| 7. | World Conference on Medical Education of the World Federation for Medical Education. Edinburgh, Scotland; 7-12 August 1988. Available at www.wfme.org/ projects/wfme-publications/99-the-edinburgh-declaration/file . (accessed on 4 Sep 2017). [Google Scholar] |

| 8. | Hanson JL, Balmer DF, Giardino AP. Qualitative research methods for medical educators. Acad Pediatr 2011;11:375-86. [Google Scholar] |

| 9. | Fish D, Coles C. Medical education: Developing a curriculum for practice. Maidenhead:Open University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar] |

| 10. | Polanyi M. Personal knowledge: Towards a post-critical philosophy. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul; 1962. [Google Scholar] |

| 11. | Royal College White Paper Series. Future of medical education in Canada. Royal College White Paper Series; 2010. [Google Scholar] |

| 12. | Imrie K, Weston W, Kennedy M. Generalism in postgraduate medical education. FMEC PG Consortium; 2011. [Google Scholar] |

| 13. | Jacob KS. Theorizing medical practice for India. Natl Med J India 2017;30: 183-6. [Google Scholar] |

| 14. | Boelen C. Social accountability: Medical education’s boldest challenge. MEDICC Rev 2008;10:52. [Google Scholar] |

Fulltext Views

1,394

PDF downloads

266