Translate this page into:

Successful treatment of disseminated nocardiosis in a recipient of renal transplant

Corresponding Author:

Soma Dutta

Apollo Gleneagles Hospitals, Kolkata, West Bengal

India

dr.somadutta@gmail.com

| How to cite this article: Dutta S, Ray U. Successful treatment of disseminated nocardiosis in a recipient of renal transplant. Natl Med J India 2020;33:253-254 |

Nocardia is a ubiquitous environmental saprophyte found in soil, decayed organic matter and water.[1] Human infection usually occurs from either direct inoculation to skin or soft tissue or by inhalation.[2]

Approximately 100 species have been described on the basis of 16S rRNA gene sequence; among these about 30 are known to cause human disease.[1] The members of Nocardia asteroides complex are most commonly responsible for human infection. They are subclassified into six different drug susceptibility types. The most recently described species is Nocardia cyriacigeorgica.[3],[4],[5]

Nocardia species are considered opportunistic pathogens that cause serious and disseminated infection in severely immuno-compromised patients, particularly those who have had organ transplantation. However, pulmonary nocardiosis also occurs in patients with a normal immune system but with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and bronchiectasis.[1]

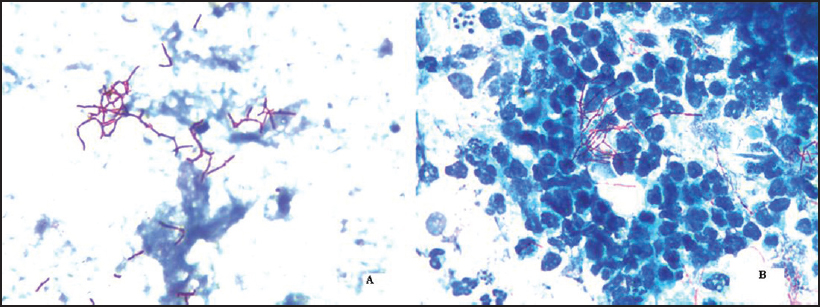

We report a 42-year-old recipient of renal transplant with disseminated nocardiosis caused by N. cyriacigeorgica. The patient was on triple immunosuppressants (prednisolone, cyclosporin-A and azathioprine) and presented with severe respiratory distress for 2 days and had had intermittent fever (maximum 102 °F) along with nonproductive cough for the preceding 2 months. Computed tomography scan revealed a right pleural effusion and consolidation in both parahilar regions with nodular changes in the right upper and middle lobes. Important laboratory findings included leucocytosis (47 510 per cmm with 96% neutrophils and 2% lymphocytes) and raised urea (88 mmol/L) and creatinine (4.6 mg/dl). Bronchoscopy showed pus and necrotizing pneumonia. The patient was intubated and ventilated, and a right intercostal drain was inserted. Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid showed branched, beaded, filamentous, Gram-positive bacilli, weakly acid-fast by modified acid-fast stain (decolourized with 1% H2SO4), suggestive of Nocardia species [Figure - 1]. Following detection of Nocardia species, the patient was treated with intravenous imipenem with renal dose adjustment (250 mg i.v. t.i.d) and co-trimoxazole. BAL fluid showed growth of a chalky white colony in blood agar and chocolate agar after 48 hours of incubation at 37 °C, as has been reported earlier.[6] A similar organism was recovered from the blood culture collected at the time of admission. The isolate was sent to the Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research (PGIMER), Chandigarh for further speciation and was identified as N. cyriacigeorgica by the matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization-time of flight (MALDI-TOF) system. The patient improved clinically and radiologically and was discharged after 2 weeks with the advice to continue co-trimoxazole (two double-strength tablets t.i.d) for 6 months. At 6-month and 1-year follow-up, there was no evidence of recurrence.

|

| Figure 1: Branched, beaded, filamentous bacilli weakly acid-fast by modified acid-fast stain (decolourized with 1% H2SO4) suggestive of Nocardia species: (i) Nocardia isolated from blood culture sample; (ii) Nocardia isolated from bronchoscopic lavage fluid |

The diagnosis of nocardial respiratory infection is difficult because of its slow growth and the presence of commensal flora, particularly in respiratory samples. Moreover, the culture plates are often discarded before Nocardia colonies are visible. A good Gram-stain smear can identify Nocardia with greater sensitivity.[7],[8]

Most of the Nocardia infections are found in patients with various degrees of immunosuppression. In immunocompetent individuals, T-cells help to eradicate Nocardia infection from the lung and thus prevent extrapulmonary dissemination. However, in immuno-compromised patients, the propagation continues unless either appropriate antimicrobials are given or cell-mediated immunity takes over.[7]

Nocardiosis occurs worldwide. Nearly all cases are sporadic. The most commonly involved organ is lung. Skin and central nervous system (CNS) are the next common sites.[9] The strain N. cyriacigeorgica was first described in 2001 in a patient with chronic bronchitis.[10] It has since been reported from western Europe, Greece, Turkey, Japan, Thailand and Canada.[3] It has rarely been reported as a cause of human infection in India. This may be an underestimation because identification requires newer molecular diagnostic techniques such as 16S rRNA gene or MALDI-TOF system. Many clinical isolates of N. cyriacigeorgica are classified and reported as N. asteroides, which would explain the underdiagnosis of this species as a cause of human infection.[3]

Peleg et al. showed that the incidence of Nocardia infection was 0.6%–3% among solid organ transplant recipients, and it has been well described in kidney (0.7%–2.6%), heart and liver transplant recipients.[11] Mortality depends on the causative species and the extent of dissemination and immunosuppression. Mortality may be as high as 77% among renal transplant recipients.[11],[12]

Studies have shown that timely diagnosis of Nocardia infection and administration of proper antibiotics can result in favourable outcomes among renal transplant recipients. Dissemination occurs mostly due to delayed diagnosis.[13]

The treatment of choice for nocardiosis in solid organ transplant recipient is long-term co-trimoxazole. Other effective antibiotics include imipenem, meropenem, amikacin, linezolid, ampicillin, third- generation cephalosporin, fluoroquinolones and co-amoxiclav. Combination therapy should be used in disseminated disease. Co- trimoxazole or amikacin along with carbapenems is usually an effective combination therapy. After definitive improvement with combination therapy, the treatment usually continues with a single oral drug, commonly co-trimoxazole. The duration of antimicrobial therapy for pulmonary or systemic infection varies from 6 to 12 months, but in case of compromised immunity or central nervous system involvement, the duration may be as long as 12 months. Nocardiosis tends to relapse frequently, so long-term antimicrobial treatment is the key to eradicate the infection. Surgical intervention should be done whenever necessary because antibiotics will not work in the presence of an abscess or pus.[1]

A high level of suspicion is essential for the possibility of nocardial infection, especially among immunocompromised patients such as organ transplant recipients.[13]

In our patient, Gram-stain and modified acid-fast stain provided a clue to the diagnosis and so treatment with specific antibiotics was started early. Two weeks of combination therapy followed by long-term oral co-trimoxazole resulted in a favourable outcome.

Acknowledgement

We sincerely thank Professor Pallab Ray, Incharge of Bacteriology Division, Department of Microbiology, PGIMER, Chandigarh, for confirmation and speciation of isolates.

Conflicts of interest. None declared

| 1. | Kasper DL, Longo DL, Fauci AS, Hauser SL, Jameson JL, Loscalzo J. Harrison’s principles of internal medicine. 19th ed. New York, NY:McGraw-Hill; 2015. [Google Scholar] |

| 2. | Corti ME, Villafañe-Fioti MF. Nocardiosis: A review. Int J Infect Dis 2003;7: 243–50. [Google Scholar] |

| 3. | Schlaberg R, Fisher MA, Hanson KE. Susceptibility profiles of Nocardia isolates based on current taxonomy. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2014;58:795–800. [Google Scholar] |

| 4. | Conville PS, Witebsky FG. Organisms designated as Nocardia asteroides drug pattern type VI are members of the species Nocardia cyriacigeorgica. J Clin Microbiol 2007;45:2257–9. [Google Scholar] |

| 5. | Wallace RJ Jr, Steele LC, Sumter G, Smith JM. Antimicrobial susceptibility patterns of Nocardia asteroides. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1988;32:1776–9. [Google Scholar] |

| 6. | Brown-Elliott BA, Brown JM, Conville PS, Wallace RJ Jr. Clinical and laboratory features of the Nocardia spp. based on current molecular taxonomy. Clin Microbiol Rev 2006;19:259–82. [Google Scholar] |

| 7. | Beaman BL, Beaman L. Nocardia species: Host–parasite relationships. Clin Microbiol Rev 1994;7:213–64. [Google Scholar] |

| 8. | Barnaud G, Deschamps C, Manceron V, Mortier E, Laurent F, Bert F, et al. Brain abscess caused by Nocardia cyriacigeorgica in a patient with human immunodeficiency virus infection. J Clin Microbiol 2005;43:4895–7. [Google Scholar] |

| 9. | Muñoz J, Mirelis B, Aragón LM, Gutiérrez N, Sánchez F, Español M, et al. Clinical and microbiological features of nocardiosis 1997–2003. J Med Microbiol 2007;56:545–50. [Google Scholar] |

| 10. | Yassin AF, Rainey FA, Steiner U. Nocardia cyriacigeorgici sp. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2001;51:1419–23. [Google Scholar] |

| 11. | Peleg AY, Husain S, Qureshi ZA, Silveira FP, Sarumi M, Shutt KA, et al. Risk factors, clinical characteristics, and outcome of Nocardia infection in organ transplant recipients: A matched case–control study. Clin Infect Dis 2007;44:1307–14. [Google Scholar] |

| 12. | Santamaria Saber LT, Figueiredo JF, Santos SB, Levy CE, Reis MA, Ferraz AS. Nocardia infection in renal transplant recipient: Diagnostic and therapeutic considerations. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo 1993;35:417–21. [Google Scholar] |

| 13. | Mwandia G, Polenakovik H. Nocardia spp. pneumonia in a solid organ recipient: Role of linezolid. Case Rep Infect Dis 2018;2018:1749691. [Google Scholar] |

Fulltext Views

2,404

PDF downloads

1,302