Translate this page into:

The MAHSA University, Malaysia's medical student oath and a comparison of various oaths

2 Department of Personal and Professional Development, Faculty of Medicine, MAHSA University, Jalan SP 2, Bandar Saujana Putra, 42610 Jenjarum, Selangor, Malaysia

Corresponding Author:

Madhumita Sen

Department of Personal and Professional Development, Faculty of Medicine, MAHSA University, Jalan SP 2, Bandar Saujana Putra, 42610 Jenjarum, Selangor

Malaysia

madhumita@mahsa.edu.my

| How to cite this article: Jegasothy R, Sen M. The MAHSA University, Malaysia's medical student oath and a comparison of various oaths. Natl Med J India 2019;32:161-166 |

Abstract

When students enrol in a medical school, they are not introduced to any ethical issues until later in the curriculum. The Hippocratic/physician’s oath is taken upon graduation. A student oath is important to introduce students to the solemnity of the education they are dedicating themselves to. This oath is analysed and compared with the doctor’s oath upon graduation and a few other oaths.

Introduction

The medical student’s oath is usually administered by various medical schools at the time of the student starting the professional course or at the time of entering their clinical years. It is to signify the entry of the student to a time-honoured profession and will usually inculcate historical and ethical aspects to guide the behaviour of the new entrant to the profession. It is sometimes held together with a white coat ceremony which is a physical manifestation of the wearing of an emblem of the profession by the student, helped by a professor, which also indicates the importance of role modelling to the student. The Faculty of Medicine at MAHSA University in Malaysia is a new entity that has so far produced 380 graduates in the workforce in the Malaysian public health sector since 2014. It is accredited by the Malaysian Medical Council and Malaysian Qualifications Agency, which are the local regulatory bodies and internationally by other bodies such as the Thai and Brunei Medical Councils. It is also listed in the International Medical Education Directory and Foundation for Advancement of International Medical Education and Research, which allows the graduates to sit for the United States Medical Licencing examination.

We wish to introduce the medical student’s oath administered at MAHSA University, which inculcates elements of patient safety for the first time compared to other well-known oaths.

The White Coat Ceremony and the Medical Student’s Oath

A ‘white coat’ ceremony functions as an initiation promise for students entering medical school. The white coat reminds doctors of their professional duties, as prescribed by Hippocrates, to lead their lives and practice their art with integrity and honour. The white coat is a symbol of the medical profession.

Oaths are not a legal obligation and therefore cannot guarantee morality. Hence, why should doctors take an oath at all? In 1992, a British Medical Association working party found that affirmation may strengthen a doctor’s resolve to behave with integrity in different clinical and interpersonal circumstances.[1]

History

The white coat originated in scientific laboratories and was worn by laboratory technicians until the late 19th century when it was adopted as the standard apparel by physicians as they wished to apply scientific principles to the practice of medicine.[2]

The White Coat Ceremony (WCC) began in 1993 at Columbia University’s College of Physicians and Surgeons and has since spread across the USA and the world. Since its inception in the USA, the WCC has become an important initiation phenomenon in many other countries.[3] It is now practised at the beginning of their academic studies at many medical schools and is dedicated to endorsing and encouraging professional and moral development and humanism in medicine.

A study on WCCs in American medical schools was mapped to four domains: professionalism, morality, humanism and spirituality. The oath focused on humility and generosity. The study showed that WCCs did not celebrate the status of an elite class but marked the beginning of educational, personal and professional formation processes and urged students to develop into doctors ‘worthy of trust’.[4] Therefore, oath-taking can be described as a student’s promise to himself/herself and society to be a professional and humanistic doctor, not a pledge to become a member of an exclusive club.

However, which oath should a medical student take at the beginning of their medical school years, before they are aware of what being a good doctor entails? Concerning the use of oaths, philosopher and bioethicist Robert Veatch asserts that the oath is thrust on students before they are able to decide whether they can agree with it or live up to it. Veatch suggests the use of a personalized student honour code rather than the Hippocratic oath. Because of the diversity of ethical traditions, ‘an oath to practise medicine according to one particular, idiosyncratic moral code … is not defensible’.[5]

When a student takes an oath during the WCC, he or she is promising to behave honourably as a medical student, not as a physician. Therefore, in the context of a WCC, the pledge is to learn within the parameters of these values as a student, not a practising physician (the values for which are exemplified in the Hippocratic oath). Obviously, the task of composing the declaration is a long and difficult one.

The Faculty of Medicine, MAHSA University’s student oath was composed by the first author. MAHSA University evolved from the Malaysia Allied Health Sciences Academy which started as a nursing college.

Personal ethics

Cultural, religious and moral traditions are important, especially in an ethnically diverse society like Malaysia. However, there are certain values and responsibilities in medicine that, in principle, need to be followed since they represent medicine’s science and art of practice.

For instance, a medical duty to conduct a comprehensive physical examination exists notwithstanding personal, religious and cultural beliefs surrounding modesty, bodily privacy and interaction with those of the opposite sex. The professional development that begins with the WCC should include reflection on these possible issues and any personal conflicts they may give rise to. A pledge to reflect on them honestly as a student is the beginning of that process. Medical morality is reinforced by medical training, both within and outside the classroom.

The Oaths in Comparison

Comparison with western medical oaths

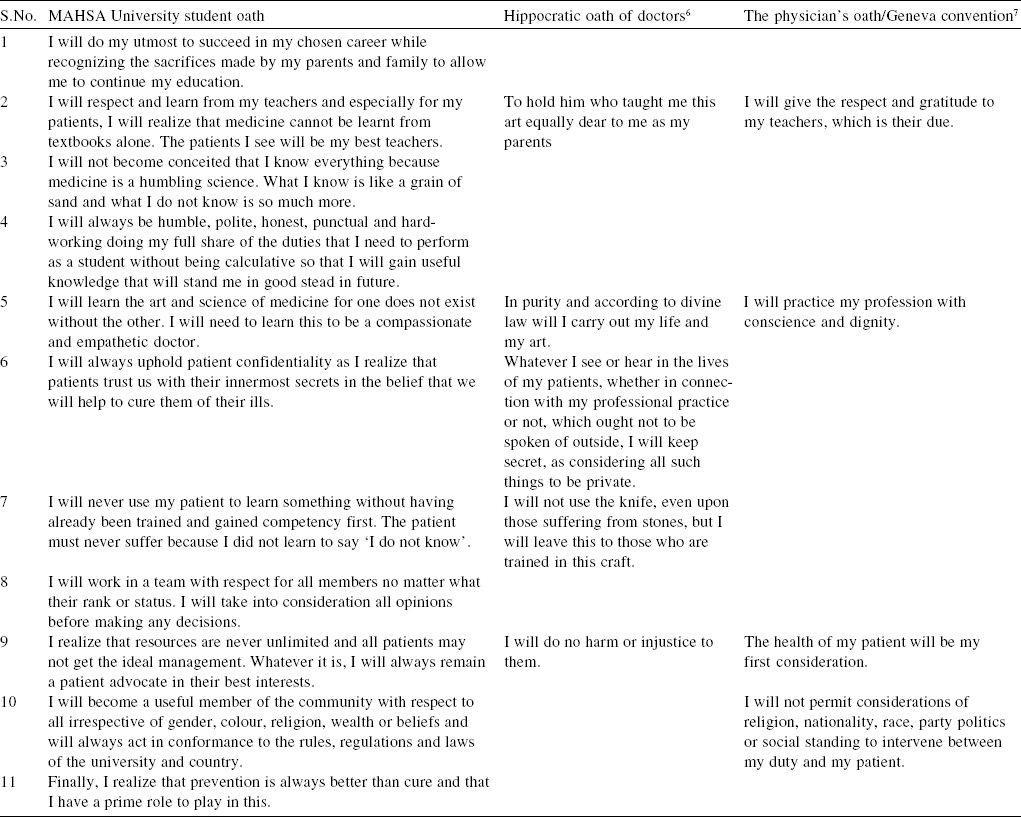

The purpose of this article is not only to explain the student’s oath of MAHSA University’s Faculty of Medicine but also to compare the various oaths as they are in use today [Table - 1].[6],[7] The MAHSA medical student oath is listed in the first column of each table.

As stated by Veatch, a student entering medical school at the beginning of his/her career should not be taking the Hippocratic oath, which is a code of medical practice. The MAHSA oath is therefore a student oath committed to a promise of learning and also an acknowledgement of gratitude to those who have made sacrifices to enable the student to tread on this hallowed path.

Many points of the MAHSA student oath underline the moral principles of the Hippocratic oath and the Oath of the Geneva Convention [Table - 1].[6],[7] At the same time, the MAHSA oath affirms the Malaysian cultural values of being ‘humble, polite, honest, punctual and hard-working’, as well as the promise of lifelong learning which is an important part of being a doctor (‘What I know is like a grain of sand but what I do not know is so much more’). In today’s world, where lifestyle diseases have significantly overtaken infectious causes of morbidity and mortality, healthy lifestyles form an important method of patient management. This is affirmed in the promise that ‘prevention is better than cure’ (point 11).

Comparison with other undergraduate student oaths

MAHSA University, apart from accepting students from Malaysia, also has a large number of international students. The student’s oath too reaffirms this cultural diversity. A brief comparison has been made with WCC oaths of two western and one eastern university [Table - 2].[8],[9],[10]

The basic concepts of promises to learn the art and science of medicine remain universal (point 5).[8],[9] The concept that a doctor is not omniscient is a great improvement from the paternalistic attitude of yesteryears: ‘The patient must never suffer because I did not learn to say “I do not know” (point 7).[8],[9] The present perception of the general population as well as many who join medicine is that a doctor is only interested in monetary gain. A promise that ‘I will always remain a patient advocate in their best interests’ is an important promise for a student to be aware of (point 9). This is highlighted in the UK student oath as well.[8] ‘I will become a useful member of the community with respect to all irrespective of gender, colour, religion, wealth or beliefs’— point 10 is echoed in all the student oaths studied.[8],[9],[10]

Prevention is better than cure is an important concept to learn even as the student learns all about the treatment of diseases (point 11 and UK oath).[8]

Comparison with eastern medical oaths/Malaysian Medical Association guidelines

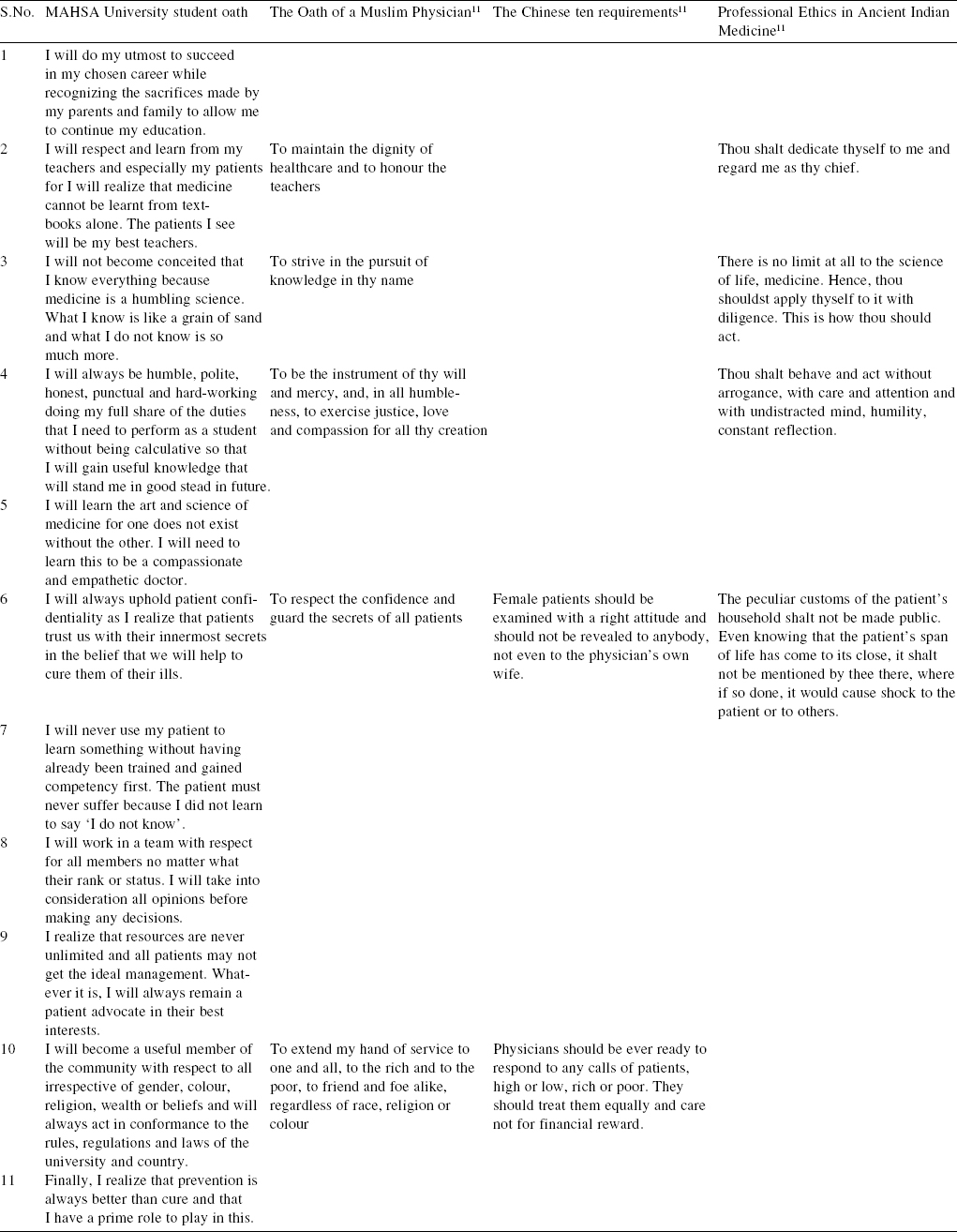

The Malaysian Medical Association (MMA), acknowledging Malaysia’s multi-ethnic and multicultural diversity, has referenced three separate oaths in its ethics code.[11]

The three main oaths listed in the ethics code of the MMA are compared in [Table - 3].[11] These comparisons not only highlight the commonalities between various oaths but also clearly show us that all doctors are healers first. Religion and other differences become secondary. Our university’s inclusive ideology enables each student taking the oath to identify completely with the promises they make, without the need for individual oath taking at this stage in their careers.

Points 2, 3 and 4 are about respect for teachers, the importance of learning and to always remain humble. Point 6 embodies patient confidentiality which remains an important ethical issue today in view of the internet. Point 10 compares a student’s and a doctor’s social responsibility.

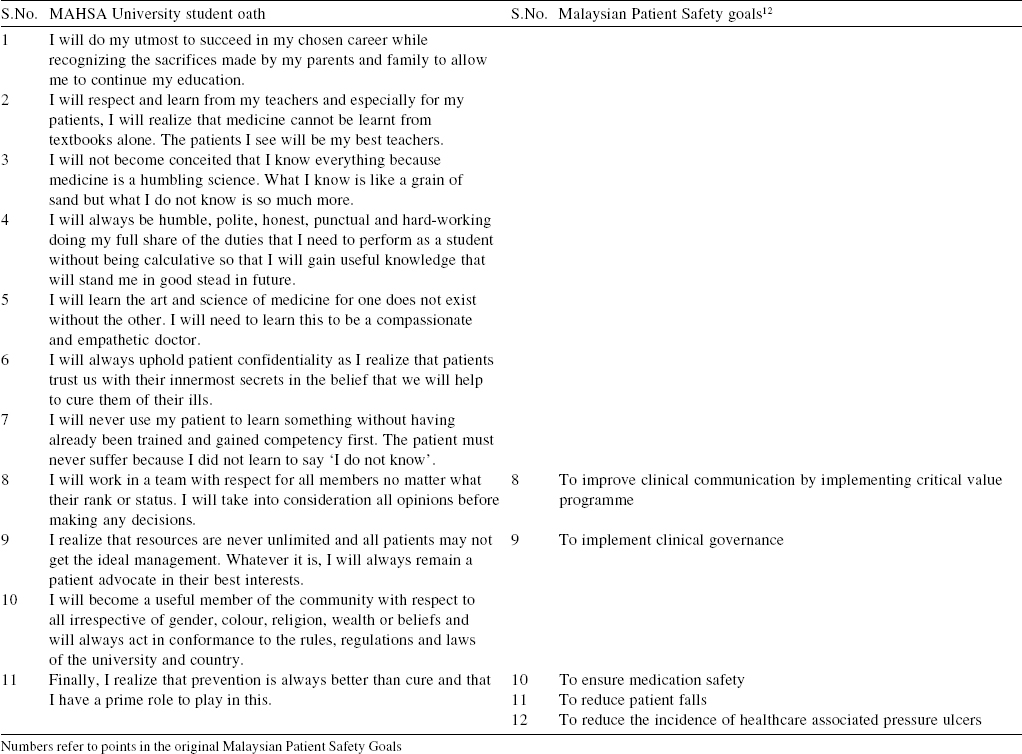

Comparison with Malaysian patient safety goals The MAHSA University student oath has an extra provision; in view of the importance of patient safety in medical care today (a point that was often ignored in the paternalistic culture of earlier medical education methods), the MAHSA oath incorporates the basic Malaysian Patient Safety Goals [Table - 4].[12] These particular provisions (points 7, 8, 9 and 11) allow a new medical student to be aware of the concept of patient safety even as they begin their medical studies.

Conclusion

Oath-taking is a promise made to oneself and to society and is considered a rite of passage for a medical student. It is a realization of a doctor’s social contract with society. For the student, it emphasizes his or her final aim of exemplary patient care.

‘For the secret of the care of the patient is in caring for the patient’, said Francis W. Peabody, an American physician in the early 20th century. While technology advances at a breakneck pace, the simple art of patient care has begun to take a back seat. Bringing oath-taking into the forefront of a student’s life as they enter medical school can help them focus on this important aspect of ethics right from the beginning of their career. Each part of this affirmation is explained to them by senior doctors who can personally identify with these precepts.

The solemnity and grandeur of a WCC make the occasion a memorable event in the lives of students. The idea is to bring to the forefront of the student’s mind the ideology of holistic patient care, which is often lost in day-to-day studies and knowledge acquisition during medical education.

Conflicts of interest. None declared

| 1. | Sritharan K, Russell G, Fritz Z, Wong D, Rollin M, Dunning J, et al. Medical oaths and declarations. BMJ 2001;323:1440-1. [Google Scholar] |

| 2. | Blumhagen DW. The doctor’s white coat. The image of the physician in modern America. Ann Intern Med 1979;91:111-16. [Google Scholar] |

| 3. | Gillon R. White coat ceremonies for new medical students. J Med Ethics 2000;26: 83–4. [Google Scholar] |

| 4. | Karnieli-Miller O, Frankel RM, Inui TS. Cloak of compassion, or evidence of elitism? An empirical analysis of white coat ceremonies. Med Educ 2013;47:97-108. [Google Scholar] |

| 5. | Veatch RM. White coat ceremonies: A second opinion. J Med Ethics 2002;28:5-9. [Google Scholar] |

| 6. | Greek Medicine—The Hippocratic Oath. Available at www.nlm.nih.gov/hmd/greek/ greek_oath.html (accessed on 5 Jun 2017). [Google Scholar] |

| 7. | WMA Declaration of Geneva. Available at www.wma.net/en/30publications/ 10policies/gl/ (accessed on 14 Nov 2016). [Google Scholar] |

| 8. | The Student Room. Does your medical schools have you swear the modern Hippocratic oath upon graduation. Available at www.thestudentroom.co.uk/showthread.php?t= 1912457 (accessed on 16 Jul 2017). [Google Scholar] |

| 9. | University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences. Available at http://medicine.uams.edu/ files/2015/08/2015_16_Student_Oath.pdf (accessed on 14 Nov 2016). [Google Scholar] |

| 10. | The Oath of a Medical Student. Available at www.csmu.edu.cn/eng/article/615.html (accessed on 14 Nov 2016). [Google Scholar] |

| 11. | Code of Medical Ethics (The Code). The Malaysian Medical Association. Available at www.mma.org.m-y/images/pdfs/Link-CodeOfEthics/MMA_ethicscode.pdf (accessed on 5 Jun 2017). [Google Scholar] |

| 12. | Patient Safety-Together For Safety. Available at http://patientsafety.moh.gov.my/ (accessed on 14 Nov 2016). [Google Scholar] |

Fulltext Views

3,878

PDF downloads

1,143