Translate this page into:

Tumour-induced osteomalacia due to thymolipoma

How to cite this article: Ahari K, Vijayan N, Garg MK, Shukla R, Choudhary R. Tumour-induced osteomalacia due to thymolipoma. Natl Med J India 34:2021;189-90.

Tumour-induced osteomalacia (TIO) is a rare paraneoplastic syndrome due to secretion of fibroblast growth factor-23 (FGF-23) from tumours located in extremities or head and neck and rarely in the thorax.1–4 We report a patient with TIO caused by a thymus tumour. The patient recovered following resection.

A 31-year-old woman presented with bilateral hip and thigh pain with difficulty in walking for the past 4 years. She was bedridden but did not suffer from any other systemic illness or fractures. Neurological examination revealed grade 3 power in both hip joints without wasting and normal tendon reflexes. Other systemic examination was unremarkable. Local examination showed focal tenderness over bilateral hip joints and pain on passive movement.

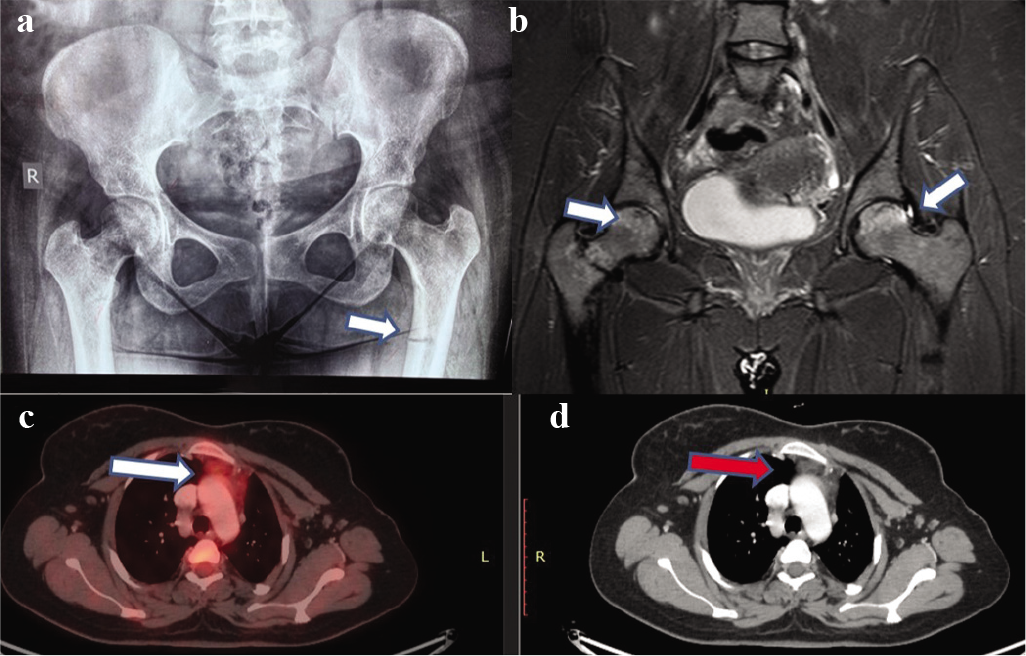

Her investigations showed persistent normal serum calcium (9.43 mg/dl) with low serum phosphate levels (1.21 mg/dl) and raised serum alkaline phosphatase (192 U/L). Serum 25-hydroxy-vitamin D was 25 ng/ml, 1,25-dihydroxy-vitamin D level was 13.5 pg/ml and intact parathyroid hormone was 78.7 pg/ml. Radiological examination showed pseudofracture on the medial aspect of the proximal shaft of both femurs (Fig. 1a), and MRI of the hip revealed grade 2 avascular necrosis of bilateral femoral heads (Fig. 1b). A provisional diagnosis of hypophosphataemic rickets was made. Her mean urinary phosphorus was 0.43 g/24 hours and urinary creatinine was 0.99 g/24 hours with calculated fractional excretion of phosphorus (FePhosphorus) of 14.7%, tubular reabsorption of phosphorus (TRP) of 85.7% and TmPO4/GFR of 1.09, which confirmed renal phosphate wasting.

- (a) X-ray hip revealing pseudofracture; (b) MRI scan showing avascular necrosis of the hip; (c) 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography; and (d) CT showing increased uptake and a lesion in the thymus

Her serum FGF-23 level was markedly high at 1880 RU/ml (normal 0–150 RU/ml). She underwent 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (18F-FDG PET)/CT scan, which revealed an ill-defined hypodense lesion measuring 19 mm×13 mm in the anterior mediastinum causing indentation on the sternum and great vessels (Figs 1c and d). The patient underwent video-assisted thoracoscopic resection of the thymic mass. Histopathology was suggestive of thymolipoma.

She recovered well and was discharged on postoperative day 7. After 15 days of surgery, the patient was evaluated for biochemical improvement. Her serum phosphates (4.5 mg/dl), serum alkaline phosphatase (94 U/L) and serum FGF-23 (125.2 RU/ml) normalized. Her FePhosphorus decreased to 5.95%, and TRP and TmPO4/GFR increased to 94.05% and 4.18, respectively. After 3 months, she was pain-free, was ambulant without support and was performing all household activities.

Localization of a tumour causing oncogenic osteomalacia is often difficult.2 In our patient, 18F-FDG PET/CT showed a lesion in the thymus, and histopathology confirmed it to be thymolipoma, which has also not been previously reported causing TIO to the best of our knowledge. TIO is usually caused by mesenchymal tumours. The thymus contains cells of different lineages: epithelial cells, mesenchymal cells, endothelial cells and dendritic cells. Histologically, thymolipomas are encapsulated tumours composed of adipose cells and thymic tissue containing epithelial cells, immature lymphocytes and Hassall corpuscles. It is postulated that thymolipoma arises histogenetically from thymic fat and/or neoplastic thymic epithelial cells combined or replacing each other. Thymolipoma may be associated with autoimmune symptoms such as anaemia, hypogammaglobulinaemia, hyper-thyroidism and, most frequently, myasthenia gravis.5 In view of the thymic lesion, the patient was evaluated for myasthenia gravis with repetitive nerve stimulation test, neostigmine test and anti-cholinesterase antibodies. All were negative.

There is no report of avascular necrosis of femoral head in TIO in the literature. She underwent laparoscopic thoracic exploration and removal of the tumour. This modality of treatment for TIO is possibly the first in the literature. Postoperatively, her symptoms improved dramatically and she became ambulant without support. Her biochemical profile showed normalization of serum phosphate and other related parameters including FGF-23. This indirectly provided evidence that the thymic tumour was the culprit. This could have been further supported by immunohistochemistry6 or reverse transcriptasepolymerase chain reaction;7 however, facilities for both were not available.

Conflicts of interest

None declared

References

- Tumour-induced osteomalacia: Experience from three tertiary care centres in India In: Endocr Connect. 2019. pii - EC-18-0552R1

- [Google Scholar]

- Tumour induced osteomalacia in head and neck region: Single center experience and systematic review In: Endocr Connect. 2019. pii - EC-19-0341

- [Google Scholar]

- Treatment and outcomes of tumor-induced osteomalacia associated with phosphaturic mesenchymal tumors: Retrospective review of 12 patients. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2017;18:403.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oncogenic osteomalacia should be considered in hypophosphatemia, bone pain and pathological fractures. Endokrynol Pol. 2012;63:234-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesenchymal tumours of the mediastinum. Part I. Virchows Arch. 2015;467:487-500.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Immunohistochemical and molecular detection of the expression of FGF23 in phosphaturic mesenchymal tumors including the non-phosphaturic variant. Diagn Pathol. 2016;11:26.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RTPCR analysis for FGF23 using paraffin sections in the diagnosis of phosphaturic mesenchymal tumours with and without known tumour induced osteomalacia. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;33:1348-54.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]