Translate this page into:

A pioneer of maternal health: Jerusha Jhirad, 1890–1983

Corresponding Author:

Mridula Ramanna

153, ‘Harini’, 4th Main Road, Malleshwaram, Bengaluru, Karnataka

India

mridularamanna@hotmail.com

| How to cite this article: Ramanna M. A pioneer of maternal health: Jerusha Jhirad, 1890–1983. Natl Med J India 2019;32:243-246 |

The appallingly high maternal and infant death rates in colonial India attracted the attention of British health officials and were characteristically ascribed by them to traditional methods of birthing, superstition and the dai, who were demonised in the colonial discourse. Indian reformers took the initiative in founding and funding maternity facilities in colonial Bombay (renamed as Mumbai) from the mid-19th century.[1] The first obstetric institution opened in 1851, was attached to a general hospital, the Jamsetjee Jeejebhoy Hospital. However, the numbers of patients were few because an average Indian woman would not dream of showing herself to a doctor (a male), and the very idea of hospitalization for something as ‘domestic’ as childbirth was unheard. In 1882, the Medical Women for India Fund was set up by social reformer Sorabji Shapurji Bengali and American businessman George Kittredge, with the dual objectives of providing western medical education to women and establishing a hospital for women and children to be managed by women. One of Kittredge’s Indian friends had lost his favourite daughter in childbirth, and hence his support to the cause. Bombay University opened its doors in 1883, to women medical students, at Grant Medical College (GMC) which had been founded in 1845, and the first batch of women passed out in 1888. The first hospital and dispensary exclusively for women and children, Cama Hospital (CH), was founded in 1886, with a generous donation from the business magnate Pestonji Hormusji Cama.

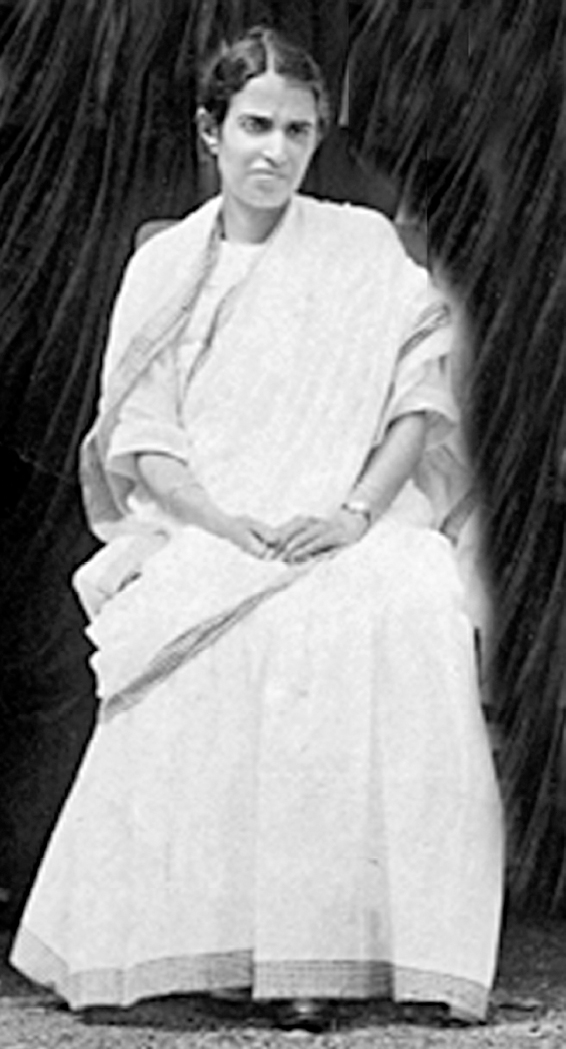

Given this background, this article focuses on Jerusha Jhirad [Figure - 1], a remarkable woman physician, obstetrician and a pioneer of maternal health in India. Jhirad was the first Indian to serve as a medical officer, from 1928 to 1947 at CH. A dream realized is the title of her biography written by her niece, Abigail Jhirad, based on conversations that she had with her aunt, and includes Jerusha’s brief autobiography, written in 1975.[2] I have used as primary sources both this work and Jhirad’s own writings and views, articulated in medical forums and in women’s organizations. Her observations on obstetric issues, maternal and infant mortality and birth control show how Jhirad perceived her role as a healer.

|

| Figure 1: Dr Jerusha Jhirad |

Family Background and Education

Born in Shivamogga, Karnataka, in 1890, Jerusha Jhirad belonged to the Bene Israel community, which traced its presence in India to the 12th century. According to legend, this community was one of the twelve lost tribes of Israel, whose ships were wrecked on the shores of the Konkan Coast, south of Bombay. The survivors were believed to have settled in neighbouring villages and taken up oil pressing as an occupation. Since they refrained from work on Saturdays, they were known as Saturday oil pressers. They later took to agriculture and adopted the name of the village, in which they settled. Thus, there was a village called ‘Jirad’, and the surname adopted by Jhirad’s ancestors was Jiradkars. Since Jerusha Jhirad’s great-grandfather served the British army during the 1857 uprising, he was rewarded by the British government with a plot of land in Pune. Her maternal grandfather was a civil engineer and worked in the erstwhile princely state of Mysore. Jerusha Jhirad’s father was a medical student when he was married, but the responsibilities of a growing family made him give up his studies to manage his father-in-law’s coffee estate in Mysore (present day Mysuru). However, this turned out to be a failure, and he moved north to a job in the railways, leaving Jerusha Jhirad’s mother and siblings in Bombay. They were a family of four sisters and three brothers; the two older sisters were married early, while the younger sister Leah stayed home and took care of their ailing mother. It seems that only Jerusha, among the sisters, pursued higher education. One of the brothers, Solomon, also became a doctor and served in the railways.

Jhirad had her early education at the High School for Indian Girls, Poona, where she fared well as a student, won scholarships and hence was self-supporting. Interestingly, she studied Sanskrit instead of Hebrew because she could not afford the fees for the private tuition in the latter language. She completed her school-leaving matriculation examination, in 1907, securing second place in the university (it was a university examination then) and receiving a number of scholarships, which enabled her to pursue medical studies.[3] Jhirad took the decision to study medicine, at the age of 11 years, when she was deeply impressed by the marvellous recovery made by her sister from a serious illness, under treatment provided by Dr Annette Benson, the Medical Officer of CH. Subsequently, Jhirad pursued her medical education, at the GMC, winning scholarships and prizes, and graduated, topping her class, with a licentiate of medicine and surgery (LMS) degree in 1912. Jhirad observed that there were few women at GMC, when she was a student, and opined that they were ‘quiet’ because ‘it was easier to be retiring than forward’.[3] She displayed an aptitude for medicine and was often called upon by her teachers, to discuss the diagnosis and treatment of cases.

After graduating, Jhirad set up private practice in general medicine, in Bombay, since residents’ posts were not available to women. She rented rooms, which included a small dispensary, waiting room and examining room. Her first patients were ‘Arab’ women, who were the wives of merchants. Soon, her practice grew and she was conducting home deliveries. Although the experience was different from hospital conditions, she found that the women reposed trust in her ability and that gave her confidence.

While Jhirad’s aim was to get an MD degree from London, she did not have the required qualification, which was to be a medical officer at a hospital. She also found that scholarships for postgraduate study were open only to men. However, in 1914, she secured a loan scholarship, from the House of Tatas, for her MD in obstetrics and gynaecology at the London School of Medicine for Women (LSMW) which had been established in 1874. Six months into her stay there, she was awarded a scholarship, of 200 pounds per annum, for 5 years, by the Bombay Government, as a special case.[4] However, Jhirad found that she had first to do the MBBS degree and then apply for a resident’s post to complete her MD from London University. Medical women were not easily admitted, and even when they were, British women were given preference. Nevertheless, when the First World War broke out, in 1914, medical men were called up for war service, and hence, women doctors were welcomed at general hospitals. Consequently, Jhirad was taken in as an intern, at the Elizabeth Garrett Anderson Hospital, London, where she worked for 2 years. Her work, here, was appreciated, and her supervisor, Miss Chadburn, permitted her to perform abdominal operations. Jhirad observed that even in Britain, at the time, home deliveries were the norm. She described the case of a frightened girl of 14 years accompanied by her grandmother, sent by the outpatient department of the hospital, to Jhirad, because she had abdominal discomfort and an enlargement. This was diagnosed as an ovarian tumour, much to the relief of the young patient, who had feared that she was pregnant. Two weeks later, the girl and her grandmother returned to thank the doctor for her ‘kindness’.[5] Jhirad seems to have been impressed by the medical social work undertaken by the well-to-do in Britain. Jhirad worked for a few months, in 1918, as a house surgeon, in a maternity hospital, in Birmingham, where her patients were factory workers. Finally, in 1919, she secured her MD in obstetrics and gynaecology, being the first Indian woman to do so, and is mentioned among the notable graduates of LSMW.

Career in India

After her return to India, Jhirad started consulting practice in Bombay. However, in 1920, she was called to Delhi, to fill a temporary vacancy at the Lady Hardinge College and Hospital, the women’s medical school started in 1916. She does not seem to have liked the city as she admitted to Abigail and accepted the post of senior surgeon at the Bangalore Maternity Hospital. This was a small hospital with facilities only for obstetric work and no operation theatre, with surgical cases being operated on in the general hospital. She set up proper antenatal, postnatal and intranatal care, with the support of donors coming forward to fund a model labour ward. Blood transfusions were organized from the lists of volunteers. Since there were no blood banks, the doctor and staff did the blood grouping and cross-matching. Full of self-assurance and dignity, Jhirad, on one occasion, refused to accommodate a Scottish woman patient (called Maggie), out of turn, even though the nurses and midwives wanted her to be taken in first. Interestingly, this patient and she subsequently became friends.[6]

Returning to Bombay, late in 1924, Jhirad started private practice and worked as an honorary surgeon from 1925 to 1928 at CH. Till 1928, the post of medical officer was held by British women, but Jhirad realized her childhood ‘dream’, when she was appointed to that post and served there till her retirement in 1947.[7] At the same time, she had a flourishing private practice. Under her guidance, undergraduate and postgraduate training facilities for women medical students were provided, and CH was affiliated to the GMC as a teaching hospital for women students for obstetrics and gynaecology. She maintained that there should be medical facilities and education exclusively for women, to make them more acceptable. Resident posts were trebled and the posts at CH were recognized for postgraduate degrees by the Bombay University. Later, honorary posts were created in medicine, paediatrics and general surgery. Antenatal, postnatal and ‘well baby’ clinics were organized. Special investigation of cases of sterility was undertaken, and work in the labour ward was regularized, especially with women who were admitted late in labour. The outpatient department, a pathological laboratory, diagnostic X-ray department, more quarters for nurses and residents and a hostel for postgraduate students were the extensions carried out during her tenure. Most of these were made possible by the generous donations made on the occasion of the golden jubilee of CH in 1936. Grateful patients also made contributions. A donation of ₹100 000 was made to express the gratitude of the family of Dr Jamnabai Dhurandhar Desai, one of Jhirad’s former assistants, for the successful treatment of Dr Desai by Jhirad during a severe attack of enteric fever. A modern aseptic operation theatre was built with these funds. A separate ward for neonatal care was established since Jhirad felt that excessive handling of newborn infants, by too many relatives, could expose them to infection. She secured financial support for this project from Dr Freny Cama, one of the earliest medical graduates of Bombay University, belonging to the family of the founder of CH, Pestonji Hormusji Cama.

Jhirad has left an account of her professional experiences. She found that women, particularly those in purdah, suffered from osteomalacia, due to the lack of exposure to the sun. This led to the softening of the bones of the legs and pelvis, and these women often had complicated deliveries. They would not come to the hospital, in time, for a caesarean operation, out of fear, even though anaesthesia was available. She found it a task particularly to persuade the men to consent to operations being performed on their wives. She referred to a case of ectopic pregnancy admitted to the hospital when Jhirad found an irate husband armed with a stick threatening to kill the doctor, if she operated on the patient. Nevertheless, the patient was able to persuade her husband to give his consent and she was operated on, subsequently. Interestingly, a year later, when the woman developed similar symptoms, the couple rushed to the hospital and requested that she be immediately operated.[8]

During the earthquake in Bihar, in 1934, Dr Rajendra Prasad, later the first President of independent India, contacted Jhirad for assistance in treating purdah women affected by the disaster. She arranged for volunteers, led by Dr Kashibai Navrange, another remarkable woman physician. They spent a month in the villages of Bihar, providing medical relief.

Since she was fond of teaching, Jhirad held special sessions at CH, on weekday evenings and Sundays. Postgraduates (men) from other medical colleges attended her lectures. Women doctors came from different parts of India for postgraduate study. Jhirad was both a fellow and a member of the syndicate of the University of Bombay and on the medical faculty of the neighbouring universities of Poona (now Pune) and Baroda (now Vadodara). She served as an examiner for the MBBS and the MD examinations, at the universities of Bombay, Madras (now Chennai) and Poona. Jhirad was founder member of the Federation of Obstetrical and Gynaecological Society of India and chairperson of the Maternity and Child Welfare Advisory Committee of the Indian Council of Medical Research from 1935 to 1952. She was chosen a member of the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists in 1935 and was elected fellow in 1947. She was awarded the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire (MBE) in 1945 and was bestowed the Padma Shri by the Government of India in 1966. Jhirad subscribed to the Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology of the British Empire and the American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology and frequently lent them to her students. To honour this interest, on her 80th birthday, the postgraduate library, named after her, was opened at CH.

Views on Maternal Health

While still a student, Jhirad was witness to a death from haemorrhage during childbirth which affected her. Her sister, Mariam’s sister-in-law, began bleeding after delivery, and since Dr Benson was away on holiday, the patient’s mother was adamant that no doctor (man) could attend to the patient who died soon after. In a paper that she authored, exploring the scope of medicosocial work in the area of maternal and child welfare, she expressed her candid opinions on the causes for the alarmingly high death rates among young mothers. She opined that ‘what should be a normal physiological process is morbid mostly through ignorance’.[9] A large percentage of maternal morbidity was preventable; it was ignorance and superstition that prevented access to modern methods. ‘Indians are naturally fatalists which is helpful when unavoidable accidents occur but certainly trying when confronted with remediable complications.‘[10] She maintained that old mothers and grandmothers continued to hold sway in Indian families and continued to impart their time-honoured customs to the next generation, even as meetings were being held in town halls, to organize welfare activities. It was therefore little wonder that doctors met with the ‘adamantine resistance’ of the younger generation. The dais were regarded indispensable by families who had a prejudiced view about doctors and midwives. While the dais would have to unlearn their traditional and unhygienic obstetric practices, Jhirad believed that they could be trained and were an asset in rural areas, where other facilities were non-existent. They could be supervised. She was also hopeful that, with the increasing education of men, a change could be brought about in the thinking of the superstitious women of their families, and she recommended that classes for fathers could be a part of welfare work. While large schemes may provide big figures at the end of each year, the real work was to carry out house-to-house propaganda. For this, Jhirad advocated creating public opinion against child marriage and education in sex relations. However, she felt following western methods ‘blindly’ would only increase the prejudice of the masses and the only way of success was to evolve methods adapting to Indian ways.[11]

Under the aegis of the Indian Research Fund Association (founded in 1911 by the Government of India and the forerunner of the Indian Council of Medical Research), Jhirad conducted a statistical enquiry into the causes of maternal deaths in Bombay city (1937–38). Jhirad’s investigations found that 71.2% of the deaths occurred among the poor, who lived in congested dwellings, and the incidence of anaemia was high. Most maternal deaths were recorded to be from puerperal sepsis, which she had also found during her stint in Bangalore (now Bengaluru).[12] While appreciating the welfare endeavours already undertaken, Jhirad recommended urgent improvements in housing, bringing down food prices, education of the public on the need for a balanced diet and the organization of a blood transmission service.[13]

Closely connected with the Association of Medical Women in India (AMWI), an organization established in 1907 to represent the interests of medical women, Jhirad served as its President from 1947–57. Regular meetings were held at the CH when specific issues faced by working women were discussed, such as right pay for the job done well, maternity leave and day care for children of working mothers and the special problems of married medical women. She observed that a positive feature was that many medical women had learnt to speak up, deliver lectures and read papers, at the meetings of the AMWI. At the golden jubilee of the AMWI, in 1957, tributes were paid to her for being energetic and active throughout her career.[14] Jhirad asserted that marriage was no bar to medicine. On the other hand, it brought into relief the best qualities of sympathy and fellow feeling. Women were best suited to serve at antenatal clinics, infant and welfare centres.[15] Whether in private practice or in government service, Indian physicians were more readily accepted than their British counterparts, because of their familiarity with the local language and social practices, a better sensitivity towards inhibitions and even a greater tolerance of the dai. Later in 1949, when the Women’s Medical Service (WMS) was dissolved along with the Indian Medical Service, Jhirad with Dosibai Dadabhoy, the first Indian President of the AMWI, and Hilda Lazarus, the first Indian woman in the WMS, presented a memorandum on behalf of the AMWI to give proper status to WMS officers.[16]

Writing in The Journal of the AMWI, in 1964, Jhirad commented on the role of abortion in population control. Jhirad was not for the legalization of abortion but for the inculcation of ‘a healthier frame of mind and a reverential and dispassionate attitude of men and women towards each other’.[17] Her contention was that children should be educated to develop the right attitude towards sex, inculcating mastery over all passions, and this would develop a highly intellectual nation. Another solution to ‘sublimate the sex impulse’ could be social service organizations to give a ‘healthy outlet to pent-up energies’ and to reduce the ‘drink evil’. Carefully planned and ‘tactfully’ conducted sex education programmes would help.[18]

The Bene Israel Stree Mandal was started in 1913 to bring the women of the community together for their cultural and social advancement. Jhirad and Leah, her sister, worked actively for this organization. It ran classes in stitching, needlework, cooking and the Hebrew language for girls who had discontinued their education, after marriage. Subsequently, the Mandal opened its doors to women of other communities.[19]

Conclusion

A tribute from a contemporary who watched Jhirad closely would be appropriate. In her review of obstetrics at the CH, Avanbai Mehta, who served there for long years and was designated Assistant Medical Officer in 1933, gave credit to Dosibai Dadabhoy and Jhirad, for their high standards of professional work, tact, sympathy and administrative ability and surgical skill, respectively.[20] Their clinics were much appreciated, and under their guidance, the younger generation ‘was getting equipped for an independent career’.[20] For half a century after the introduction of medical education for women, the forte of women physicians was considered to be women’s and children’s health alone. Nevertheless, by the time of the golden jubilee of the AMWI in 1957, Jhirad could record that mixed medical colleges had women not only as professors of obstetrics and gynaecology but also teaching general medicine, orthopaedics and tuberculosis. As a representative of the AMWI on the administrative board of Lady Hardinge College, Jhirad, with her colleagues, protested against the move to make Lady Hardinge College co-educational.[21] Her contention was that people were still too conservative to let their girls study at co-educational colleges, and medical facilities and education should be exclusively for women, to make them more acceptable. Deputations by the AMWI proved ineffective, and it was only an injunction against the authorities brought by an ex-student that averted this step. Again, in 1956, the Ministry of Health tried to get the college closed and open a new co-educational college.[21] The AMWI, under the Presidency of Jhirad, strongly protested, and a memorandum was sent to the President, Vice President and Prime Minister. Subsequently, the move was given up, and the Cabinet announced that Lady Hardinge College would continue as a women’s college.[22]

Nevertheless, Jhirad gave men credit for fighting for women’s rights. Jerusha Jhirad died in 1983 at the age of 93. In the words of Abigail Jhirad, Jerusha indeed led an interesting life and was an extraordinary person. She never spent on luxury for herself and not only served others as a doctor but also gave away her money and her belongings. She is a fine example of a woman who had a dream and realized this, despite various constraints.

Acknowledgement

The author acknowledges the assistance of Dr Shubhada Pandya in locating the primary source material.

Conflicts of interest. None declared

| 1. | Ramanna M. Western medicine and public health in colonial Bombay, 1845— 1895. New Delhi:Orient Longman; 2002. [Google Scholar] |

| 2. | Jhirad A. A dream realised. Biography of Dr Jerusha J. Jhirad. Bombay:ORT India Publication; 1990. [Google Scholar] |

| 3. | Jhirad A. A dream realised. 22. [Google Scholar] |

| 4. | General Department Volumes, Maharashtra State Archives, Mumbai, no. 628, 1915, Letter no. 380; 1914. [Google Scholar] |

| 5. | Jhirad A. A dream realised. 30. [Google Scholar] |

| 6. | Ibid: 35. [Google Scholar] |

| 7. | Ibid: 7. [Google Scholar] |

| 8. | Ibid. [Google Scholar] |

| 9. | Jhirad J. Medico-social work. In: Gedge EC (ed). Women in modern India. Bombay:Taraporewala; 1929:133. [Google Scholar] |

| 10. | Ibid: 134. [Google Scholar] |

| 11. | Ibid: 137. [Google Scholar] |

| 12. | Jhirad J. Report on an investigation into the causes of maternal mortality, in the city of Bombay. Delhi:Government of India Press; 1941:24, 52. [Google Scholar] |

| 13. | Ibid. [Google Scholar] |

| 14. | Mistri JE. Golden jubilee of the association of medical women in India. Messages and congratulations. J Assoc Med Women India 1957;45:4-5. [Google Scholar] |

| 15. | Jhirad J. Women in the medical profession. J Assoc Med Women India 1960;48:9. [Google Scholar] |

| 16. | Ramanna M. Health care in Bombay Presidency, 1896-1930. Delhi:Primus; 2012. [Google Scholar] |

| 17. | Jhirad J. Role of legalization of abortions in population control. J Assoc Med Women India 1964;52:98-100. [Google Scholar] |

| 18. | Jhirad J. Practical aspects of birth control. J Assoc Med Women India 1963;51: 116-23. [Google Scholar] |

| 19. | Jhirad A. A dream realised. p. 26. [Google Scholar] |

| 20. | Mehta AM. Progress of obstetrical work in the Cama and Albless hospitals. J Assoc Med Women India 1964;52:1-10. [Google Scholar] |

| 21. | Mistri JE. Association of medical women in India. Memorandum. J Assoc Med Women India 1957;45:55-62. [Google Scholar] |

| 22. | Jhirad J. Association News. Report on the Lady Hardinge Medical College. J Assoc Med Women India 1958;46:64-5. [Google Scholar] |

Fulltext Views

4,681

PDF downloads

1,682