Translate this page into:

Albert Einstein and Jacob Chandy

[To cite: Nair KR. Albert Einstein and Jacob Chandy. Natl Med J India 2024;37:281–3. DOI: 10.25259/NMJI_261_2024]

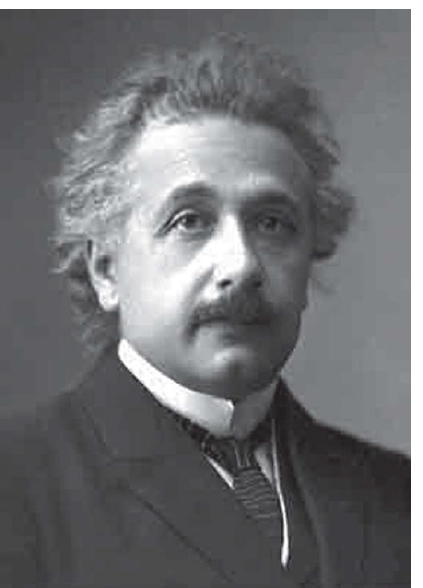

Albert Einstein (1879–1955), one of the most celebrated scientists in the world was born on 14 March 1879 in a religious Jewish family in Ulm, Germany. He was not considered as a particularly bright student during his childhood, till he joined Polytechnic Institute in Zurich (1896–1900). That was one of the most productive and pleasant periods in his life. His initial job was as a ‘third class technical expert’ in the Bern Patent office, where he got a lot of leisure time to pursue his research and publish seminal papers from 1905.

He then left the patent office to take up the post of Associate Professor in the Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich. This was followed by further brilliant research papers by which he got his professorship there. He was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1921, for his discovery of the photoelectric effect. His fame reached epic proportions, but fate took a turn when Hitler ascended as the Chancellor of Germany in 1933. This made the lives of millions of Jewish people miserable. Many of the academics had to flee Germany and took refuge in the USA, UK and other countries. Einstein took up the post of Professor of Theoretical Physics at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey, in 1933. He lived in New Jersey till his death in 1955.1

ALBERT EINSTEIN’S HEALTH ISSUES

Till about 1947–1948, he was generally well except for minor health issues. But from 1947 onwards he used to have abdominal pain off and on, which became quite severe by December 1948. It was then that he sought treatment at the Jewish Hospital in Brooklyn, New York, where the eminent surgeon Dr Rudolph Nissen (1896–1981) was working.

The investigations available to diagnose an enigmatic abdominal pain were limited then. The only further option was to do an ‘open minded laparotomy’ (an apt term which was used by one of our professors of surgery in Trivandrum [presently Thiruvananthapuram]). Dr Nissen was shocked to see an aortic aneurysm, in addition to a few intestinal cysts in Einstein.2

Dr Nissen was also a German Jew refugee in the USA and was a very successful lung and gastrointestinal surgeon. In 1948, there was no accepted surgical technique to handle aortic aneurysms. He was in a dilemma as to leave the aneurysm untreated would be quite hazardous as it could burst open at any time. Fortunately, he remembered having read in some major surgical journal that in some medical centre, someone had tried to wrap an aneurysm with a scotch-tape in a man. According to those authors, it was quite useful as it prevented further bulging of the aneurysm and induced intravascular clotting. As far as he could recall, the procedure done by them was in a subclavian artery and not in the aorta but the result was good.

Since he had nothing else to offer by way of treatment, he too did the same. To everyone’s surprise, the response was quite good. Einstein’s abdominal pains ceased and he could go back to his routine work for nearly 7 years. Nissen’s heroic procedure was lauded by all as he had saved the life of a great scientist.2,3

But after 7 years Einstein’s abdominal pains recurred. By then, better surgical procedures to tackle abdominal aneurysms were available. But Einstein refused any further surgery by saying ‘I want to go when I want to go; it is useless to prolong life artificially’. He passed away on 18 April 1955.1

- Albert Einstein

INDIAN CONNECTION OF ALBERT EINSTEIN

Apart from his professional connections with the physicists of India, he was an admirer of great Indian savants of that period. He had met Sir Rabindranath Tagore in 1930 while he was still in Berlin. Though he had not met Mahatma Gandhi personally, Einstein had great admiration for his political and social stands. One of the glowing tributes Einstein had paid to Mahatma Gandhi after his sad demise runs like this ‘Generations to come, it may well be, will scarce believe that such a man as this one ever in flesh and blood walked upon this earth’.4

INDIAN CONNECTION OF EINSTEIN’S SURGERY

It is a surprise that thus far, no one has highlighted the fact Albert Einstein had a good quality-of-life and prolongation of his life by an innovative surgical method initially tried out by two surgeons, Paul Harrison (1883–1962, an American surgeon) and Jacob Chandy (1910–2007, an Indian surgeon who later founded the neurosciences in India in 1949), in Bahrain way back in 1941.

Though I was not a student of Professor Jacob Chandy, I was close to him from 1973 till he died in 2007.5 By 1973 he had retired from Christian Medical College (CMC), Vellore and was appointed as Emeritus Professor of Neurosciences in all medical colleges in Kerala. Though he was considered a taciturn surgeon, I found him an excellent raconteur of his life and times in Arabia, USA and in CMC, Vellore. His storytelling was always pleasant to hear. However, his autobiography ‘Reminiscences and Reflections’ published in 1988 is not an easy read.6

Born in 1910, in a small village near Kottayam in a devout Christian family, Jacob Chandy had his medical education in Madras Medical College. He had no intention to join government service or any private hospital as he had made up his mind to join only a Christian medical missionary hospital. The reply he got from such medical missionary hospitals was that they could not afford a MBBS doctor but would prefer to take medical diploma holders (LMP) who asked for lower salaries.

After trying for some time in vain, he accepted the suggestion of a friend to work in the American Oil Company in Arabia. He did not like the job and planned to return to India after the contract period was over. As World War II had just started when he came to Bahrain, he could get a booking in a ship voyage to India only after two weeks. He had earlier met, the famous surgeon Dr Paul W. Harrison at the Bahrain Mission Hospital. Since he had nothing else to do in the next two weeks, he decided to pay a visit to Dr Harrison and if possible, join there as a medical missionary doctor.

As it turned out, he stayed in that hospital as Paul Harrison’s colleague for more than two and half years. It was then that Dr Chandy informed Dr Harrison about his desire to return to India to do missionary work there. Paul Harrison suggested to him to get some postgraduate training before returning to India. He arranged for his neurosurgical training in the USA.

But as they were the only available doctors in Bahrain then, they had to take up all sorts of surgery, medicine, paediatric and dermatology cases, as patients flocked to their Missionary Hospital with hope. Indeed, these doctors did their very best and they were appreciated by the locals. In addition to their routine medical work, they found time to conduct journal clubs and published many papers and case reports in prestigious journals. They had no idea how well their papers were received by others. Nor did Jacob Chandy bother too much about the general surgical papers which he published there, since he left for the USA to become a neurosurgeon.

I have read his autobiography and heard many times from him, about his surgical exploits in Bahrain. I have listened carefully to the YouTube presentation of Dr Jacob Chandy’s conversation with Dr M. Sambasivan in the American Association of Neurological Surgeons (Formerly Harvey Cushing Society).7 Though he had mentioned hilarious accounts of how he was offered 40 slaves for treating successfully a Bedouin Chief and how they managed dermatology–venereology problems there, he had never mentioned about a case report of two patients whom they treated by a scotch-tape.

ANEURYSM BINDING BY SCOTCH-TAPE

Scotch-tape was invented in 1930 by Richard Gurey Drew (1899–1980)8 and soon it became popular for many industrial, commercial and domestic uses. When Jacob Chandy was working in Saudi Arabia, it was a novelty there and hence, he bought a few to take them back home.

- Dr K.R. Nair and Dr Jacob Chandy

- Dr. B. Ramamurthi handing over the first copy of Evolution of neurosciences in India to Dr Jacob Chandy at the Trivandrum Conference of Neurosciences Society of India. December 1998. (Left to right: Dr B. Ramamurthi, Dr Jacob Chandy, Dr M. Sambasivan and Dr K.R. Nair)

It was by sheer chance that Paul Harrison and Jacob Chandy had to treat a 70-year-old ‘weather beaten old man’ complaining of pain and a pulsating mass ‘with the size of hickory nut’ in the subclavian artery on 7 July 1941. Needless to say that their diagnosis of left subclavian aneurysm was made on clinical grounds, as investigations such as an echocardiogram, doppler ultrasound, angiogram, etc. were not available then. Under local anaesthesia, they made an incision and their clinical diagnosis was proved right.

There were no recognized operative techniques to handle such a situation in those days, but Dr Paul Harrison and Dr Jacob Chandy remembered that in the previous year, there was a report by Pearce in Annals of Surgery on wrapping up the aorta in dogs with ordinary cellophane, resulting in gradual occlusion of the major vessel.9 However, there had been no such trial in any human subjects. As they had no alternate treatment modality to offer, they decided on the spur of the moment to use cellophane wrapping of the subclavian artery aneurysm of that patient. They had no idea how to sterilize the one-inch wide cellophane. They boiled it; this caused some distortion, but they used it all the same. A 5-layer binding was done and sutured. It took a few months before the pulsatile mass subsided well and the pain was relieved.

In 1942, a similar patient was operated by them and the aneurysm wrapped with cellophane but the surgical outcome was poor. These two case reports were published in Annals of Surgery in 1943.10 Though it was a seminal report, it unfortunately did not get the recognition it deserved. However, recent reports on Einstein’s surgery do include the Harrison–Chandy paper.2,3

Conflicts of interest

None declared

References

- The ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm of Albert Einstein. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1990;170:455-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Einstein’s aneurysm: Of cellophane and Rudolph Nissen. Vascular Specialist. Available at www.mdedge.com/vascularspecialistonline/article/83664/einsteins-aneurysm-cellophane-and-rudolph-nissen? (accessed on 25 Oct 2024)

- [Google Scholar]

- Available at https://youtu.be/2dj-Lyn1e8c (accessed on 25 Feb 2024).

- Available at www.scotchbrand.com (accessed on 25 Feb 2024).

- Experimental studies on the gradual occlusion of large arteries. Am Surg. 1940;112:923-37.

- [Google Scholar]