Translate this page into:

Doyle and the Edalji Case

Corresponding Author:

Ullattil Manmadhan

Sandwiched between two generations of doctors, the author is an electrical engineer with a deep interest in Indian history, and lives in North Carolina

USA

| How to cite this article: Manmadhan U. Doyle and the Edalji Case. Natl Med J India 2016;29:298-301 |

The role of medicine sometimes goes well past the borders of cure. In this particular case, it was used to not only establish a person′s innocence, but also expose the overt racism that influenced an Edwardian court of law in convicting, sentencing and imprisoning a British subject based on his origins, other flimsy conclusions and an apparent ′sinister′ appearance. It was left to a zealous crusader with a medical background to conduct a painstaking forensic investigation to prove otherwise. The person convicted was George Edalji. The crusader was none other than Arthur Conan Doyle, operating in true Sherlock Holmes style and using the mass appeal of his own creation′s abilities, to uncover the irregularities in the Edalji case and expose the acts of the erring police. His involvement was critical in prodding the bureaucracy into grudging action.

George Ernest Thomson Edalji ([Figure - 1]) was the eldest son of Shapurji Edalji, a Parsi from Bombay (now Mumbai). Shapurji′s Zoroastrian ways changed to Christian ones while schooling at Bombay′s Free Kirk College following which he went to England for a 3-year ministerial course. He married Charlotte Stoneham, who hailed from a family of ministers and as a wedding present obtained a position as the Vicar of the St Marks parish at Great Wyrley in 1875. George was born at the Vicarage, the year after. Shapurji settled down to what he would have hoped to be idyllic Staffordshire life, but it was not to be. He would soon get involved in controversies related to the well-being of the miners of the locality, the school system, Irish home rule and so on, all perhaps reasons for brushes with other local socialites. One can also feel the undercurrents of racism the family faced, a fact often mentioned in the many articles and books about the case, and you can imagine how the dour villagers of the parish felt being lectured by a black man of Hindu (so they assumed) descent, and married to an Englishwoman! But they managed and the Edalji′s were, as time went by, blessed with two more children, Horace and Maud.

|

| Figure 1. George Edalji (reproduced from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/George_Edalji) |

Great Wyrley is located about 2½ miles south of Cannock town centre. The bigger cities nearby are Birmingham and Manchester, while Stafford, Wolverhampton, Walsall and Stoke on Trent are some of the important towns in West Midlands. Farming was the main occupation and farm animals and barns quite common.

The problems in the region and particularly at the vicarage started with the first of the anonymous letters in 1888, when the Vicar received a number of them, some composed on pages from the composition books belonging to the Edalji children in the vicarage. George, then 12 years old and schooling at the Rugeley Grammar school was a suspect (his younger brother Horace and sister being too small) together with the housemaid Elizabeth Foster, then 17 years old. What started as nuisance letters went on to mention violence and became overtly racist, and soon racial graffiti began to appear in the vicarage. Sergeant Upton, the policeman assigned and Shapurji were convinced it was Foster and a police case was filed. However, as the girl was too young, harsh action was not warranted and after she pled guilty to a lesser charge of harassment, was sentenced to probation. Foster however maintained to the end of her life (also threatening revenge) that she had not written any of those letters, which left a lingering doubt in many minds that George was the writer of these virulent letters. It was in 1888 that the aristocratic and iron-handed George Anson, the second son of the second Earl of Lichfield, took over the post of chief constable of Staffordshire. Captain Anson, as is recorded, was not too amused with the way Foster was convicted and some began to feel that this was the catalyst for all the troubles thereafter.

In 1891, George joined the Masons College to study law, while the messy letters continued to get delivered at the vicarage, also the home of one W.H. Brookes and the vicarage was frequently vandalized. Sergeant Upton who investigated, as he did in the Foster affair, failed to catch the courier of those letters even after posting a watch, but now suspected George Edalji as the perpetuator and voiced these suspicions to the public and Brookes. Interestingly, the letters were either anti-Edalji, pro-police, pro-Upton, and in all cases very knowledgeable of the people of the locale. Shapurji was incensed to see his son′s name dragged around in public and tried suggesting to the police that they interview Foster and other suspects instead. However, Chief Constable Anson had decided by then that George was the guilty party.

The letters to the vicarage continued with regularity between 1892 and 1895, punctuated with many other kinds of harassing pranks, a period when George was doing well in college, winning medals and awards. Shapurji kept up his complaints to Constable Anson, who started to ignore them stating that the letters were either written by Shapurji himself or his son George. When Charlotte, Shapurji′s wife intervened, Anson threatened George′s arrest. The letters and the pranks ceased for seven years after 1896.

George Edalji began a 5-year articleship with a firm of Birmingham solicitors in 1893 and later set up his own law practice in 1899. All this time, he lived at the vicarage and took the train to come home every evening and leave in the morning. He shared a bedroom with his father, while his mother roomed with his sister Maud, who did not keep well. This was to become another important aspect in the case.

In 1903, a number of cattle maiming acts shook the sleepy village, when sheep, cows and horses had their undersides and sides slit at night, with a sharp object, after which some of them had to be put to sleep. The constabulary sprang into action, but they came up with nothing. Rumours soon began to circulate that George was perhaps the culprit and that he had been seen taking lone walks at night. Around the same time anonymous letters started again and this time the purported writers stated themselves to be members of the Great Wyrley gang. Later letters took an ominous tone, threatening the maiming of women and children, alarming the public. One of these letters also asked George to stay away as he was being considered a suspect (some of these were police ′trap′ letters). The vicarage was briefly kept under police surveillance and George considered the prime suspect by the police, with them waiting for the first opportunity to arrest him.

On 12 August, George met David Hobson, a client, at the vicarage. Hobson left at 8 p.m., following which George went out to see a bootmaker, which was observed by a number of people. He returned at 9.30 p.m., retired to sleep with his father, who as usual, locked the door. George did not step out of the room that night according to Shapurji′s testimony.

On 13 August, a pony was found maimed and Inspector Campbell tried to have George who was waiting to board his train to Birmingham, brought in to the vicarage for questioning. George declined and proceeded to his office at Birmingham. The officers sped to the vicarage to conduct a search (no other locations were searched nor others questioned) for knives and George′s clothes. They came away with a pair of pants with some mud on the cuffs, a coat with some dark spots and horse hair (which nobody else other than Campbell could see and confirm) and a pair of boots with a worn heel. The police thought they had all that was needed to implicate George and connect him to the scene of the crime. But in the meantime, a veterinary surgeon, based on study of the blood pool, placed the animal maiming at around 2.30 a.m., a time when George was asleep behind closed doors at the vicarage.

Inspector Campbell rushed to Birmingham, and arrested George. A search of his office yielded nothing of interest (his money box was emptied, during this search). Meanwhile Anson′s deputies were hard at work, comparing the shoe heel to the heel marks at the crime site, and a sample of the pony′s skin was collected. Campbell went back to the vicarage and searched further, obtaining some old razors, one of them stated to be wet. The police surgeon, Mr Butter found no trace of blood on the razors, but detected a couple of horse hair on the coat, and the coat sleeve did have a couple of spots of blood on it. So that was the police case, centred around some apparent horse hair on a coat (mentions of horse hair on the wet razor), the wet razor, spots of blood on a cuff, and a bunch of anonymous letters, unrelated to the maiming but connected to Edalji and used to prove him to be one with a vile character.

George Edalji′s trial was held in October 1903. His defence felt the case would be thrown out, but they did not assess correctly, for powerful forces were against them. A handwriting expert (unreliable as it turned out) testified that the letters were written by George, and coupled with all the circumstantial evidence mentioned above, Edalji was found guilty by the jury. The jury comprising people from Staffordshire recommended him to mercy, but Sir Reginald Hardy, the judge felt otherwise. No records of the trial were kept.

Captain Anson′s racial intent was clear when he started to describe Edalji as possessing supernatural powers, purportedly part of his ′Hindu′ heritage. He stated during the trial that he had no doubts about George′s guilt, as he possessed a sinister appearance and had eyes that glowed like cats at night. But Anson finally got what he wished, in putting away the well-educated son of the ′Hindoo Vicar′ where he belonged, behind bars. George was pronounced guilty and sent to jail, where he languished for 3 years. But the horse maiming and anonymous letters continued, disconcerting the public and the police. The police and Anson now opined that other members of George′s gang were at work.

Rev Shapurji and his friends took matters into their hand, collecting a public petition seeking a redressal of the case. Important public figures joined in, and a magazine Truth became their mouthpiece. The petition, which was signed by ten thousand people, of which it is said, there were a thousand barristers and five members of parliament, was sent to the Home office. As public pressure built up, the Home office countered with vague replies. Abruptly in 1906, George Edalji was released on parole, but as he was automatically disbarred, could not practice law. Now 30 years old, with hardly a friend, a blackened name, no proper job despite his qualifications, all due to the black acts of a racist police Constable Anson and his cronies, poor George was forced to move to London, financially supported by his father.

It was under these circumstances that George decided to send the case details to Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. Doyle decided to tackle the case and help the man who had, in his mind, nothing to do with the events and who had been treated badly. He had a meeting arranged with Edalji at the Grand Hotel. Edalji arrived early and was perusing the morning papers in the lounge, when Doyle sauntered in, a little late. It was at this juncture that Doyle observed something odd, that the young man was holding the newspaper unnaturally close to his face to read it. When quizzed about it, Edalji replied that he always had vision problems and had never found the right eyeglasses to wear. Doyle, who was a physician and surgeon trained in ophthalmology, had noticed that George was severely myopic.

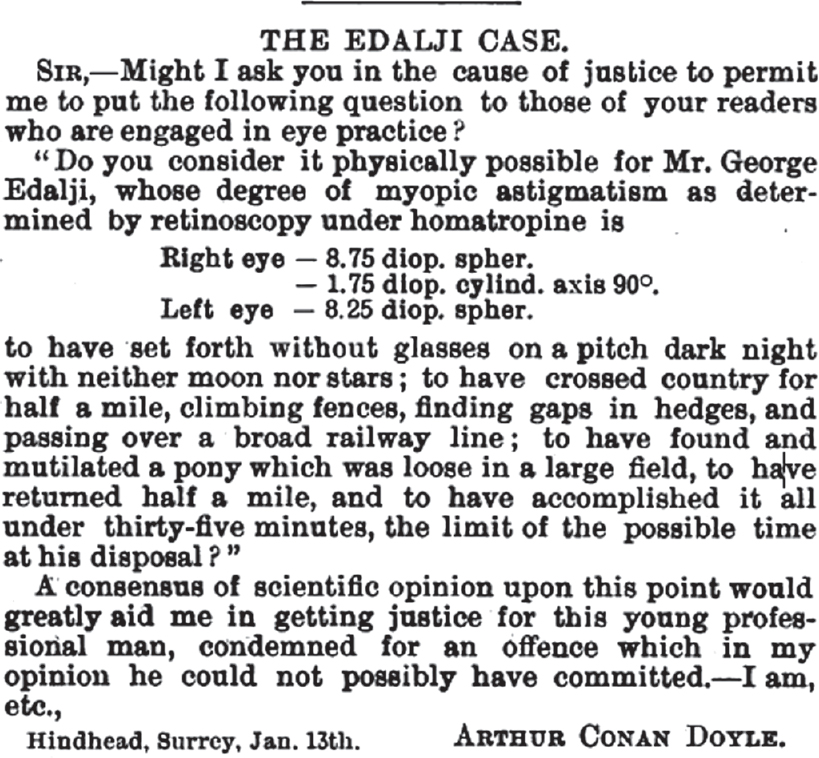

Doyle got Edalji examined by a reputed ophthalmologist, Dr Kenneth Scott, who concurred with Doyle that Edalji was indeed suffering from acute myopic astigmatism. They discussed and concluded that it was unlikely for such a short-sighted person to have walked miles in the rainy night through a darkened field, conducted the crime of pony slashing and returned in quick time. Doyle was convinced his client was innocent. Upon confronting Edalji with this medical information, Doyle learned that the defence counsel had decided to avoid the extra effort of bringing up the sight aspect assuming that the prosecution case was too weak, an error which we know now, was one of immense magnitude ([Figure - 2]).

|

| Figure 2. A write-up by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle that appeared in The Medical Press and Circular, a weekly journal of medicine and medical affairs, London, 16 Jan 1907. 1907;134:55. (Public domain book, google link http://books.google.com/books?id=D9I1AQAAMAAJ&pg=PA55 ). |

Like Doyle many others were appalled at the injustice and racist leanings in the case. Jawaharlal Nehru, then a student at Harrow mentioned the case in a letter to his father, Motilal Nehru, [9] in January 1907: ′I suppose you have heard about the Edalji case and the new phase it has taken here. Whole pages are devoted to it in some of the papers and you know what a page of a newspaper is here. The poor chap must have been quite innocent and I am sure he was convicted simply and solely because he was an Indian.′

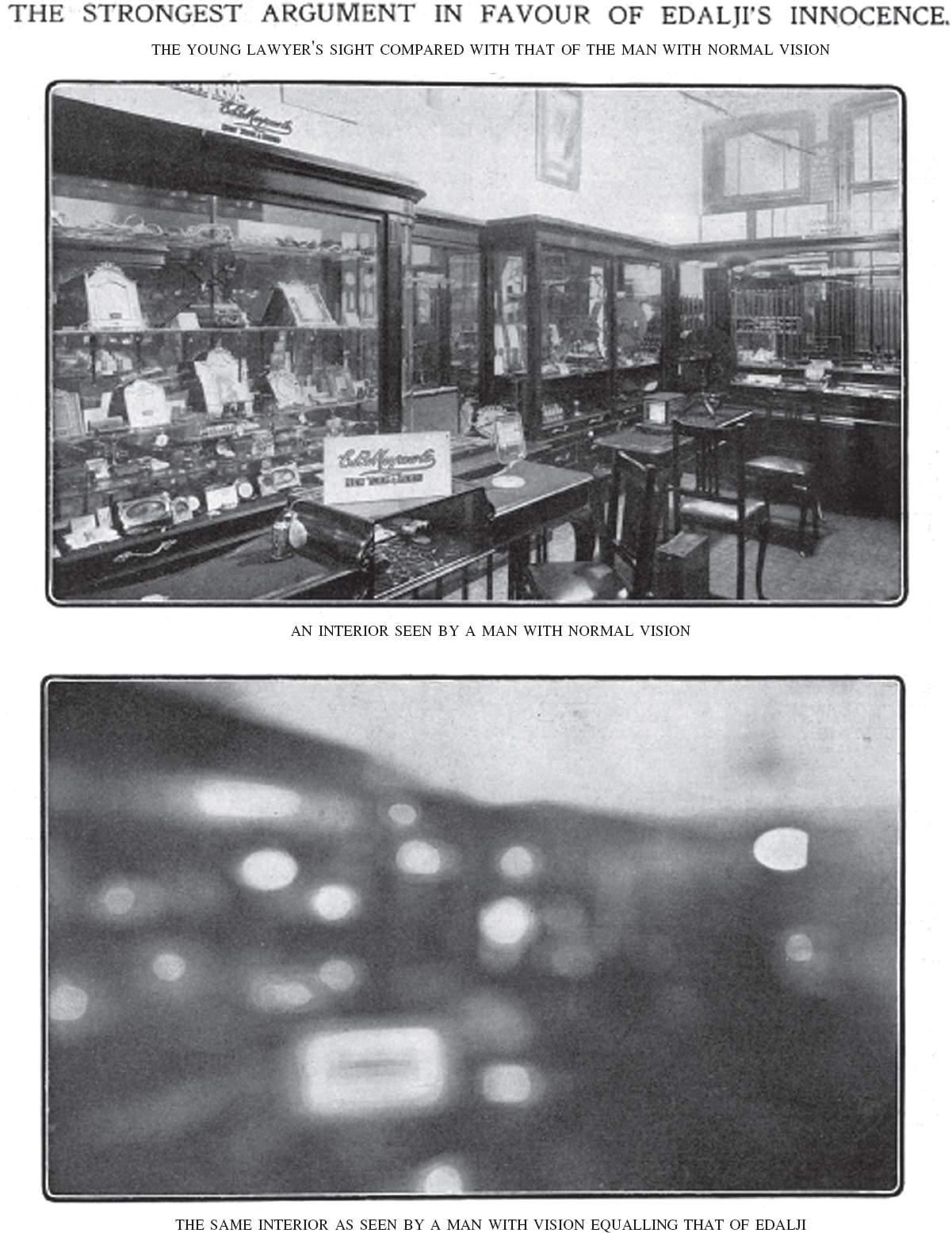

Doyle pursued the case in grand Sherlock Holmes style and started his tirade, writing for the Daily Telegraph, sans copyright, so that the news was flashed worldwide. Details hit the wires, so did Doyle′s questions [10] on Edalji′s myopic astigmatism. Doyle also provided a graphic set of images [11] so that the public understood how the world would have looked to Edalji without glasses ([Figure - 3]), but others countered that Edalji certainly went about his work and life, without glasses.

|

| Figure 3. A. A comparison of a normal and myopic person's view of a scene. (Source: Sketch: A Journal of Art and Actuality, London, Volume 57, Jan 23, 1907, page 39. Public domain book, google link http://books.google.com/books?id=BTVIAQAAMAAJ&pg=PA39 B. Harper's Weekly, Volume 51, page 845, # 2633 June 8th 1907, New York Public domain book, google link http://books.google.com/books?id=ErZCAQAAIAAJ&pg=PA845) |

In addition to all this, Doyle pointed out other anomalies [12] such as the fact that underbelly hair was introduced as evidence in court and that it was not possible to catch many strands of such hair on the accused′s coat while leaning against a pony to commit the slashing, indicating manipulation of evidence. As days went by and as Doyle started to see the depth of the police duplicity, the correspondence between him and Anson became increasingly acrimonious, both accusing each other of ungentlemanly conduct. Doyle was convinced that Edalji was completely innocent, that Anson was a consummate racist and that a local lad named Roydon Sharp (though not mentioning him by name) was the culprit. Anson on the other hand tried to mislead Doyle in a wrong direction in order to expose him as an inept armchair detective.

Doyle′s involvement and letters to the press as well as with the Home office had good effect. A three-member commission was appointed, and even though one of the members was Anson′s cousin, it found the Stafford verdict faulty. They concluded, [13] ′The result is that, in our opinion, the conviction was unsatisfactory, and after a most careful consideration of all the facts and printed evidence placed before us, we cannot agree with the verdict of the jury. On the one hand, we think the conviction ought not to have taken place, for the reasons we have stated; that conviction, in addition to the sentence of the court, necessarily brought upon Edalji the total ruin of his professional position and prospects; and as long as things continue as they are, he must remain under police supervision, a condition in which it would be extremely difficult, if not impossible, for him to recover anything like the position he has lost. On the other hand, being unable to disagree with what we take to be the finding of the jury, that Edalji was the writer of the letters of 1903, we cannot but see that, assuming him to be an innocent man, he has to some extent brought his troubles upon himself.′

H.J. Gladstone, the Home Secretary replied, [13] ′After the fullest and most anxious consideration I have decided to advise His Majesty, as an act of Royal clemency, to grant Mr Edalji a free pardon. But I have also come to the conclusion that the case is not one in which any grant of compensation can be made.′

Doyle wrote to Churchill [14] as well arguing for compensation for time unjustly served, but the Home office closed the files. Edalji, however, was reinstated to the bar and continued his legal profession, moving to Brocket Close near London. The Edalji case, followed by the Adolf Beck fraud case, led to the creation of the Criminal Court of Appeals in 1907, for until then, the only course left for a criminal was to appeal to the monarch, for pardon.

Interestingly, G.A. Anson was awarded with medals and titles over the years for his yeoman work. But subsequent maiming events made Anson look a fool and his erratic racist behaviour (verbal attacks on Charlotte, Doyle, frequent letters to the Home office, etc.) bothered people. He eventually retired from the force in 1929 after 42 years of service and passed away in 1947.

There are certainly many unresolved questions in this case, but the main issue behind the ill treatment meted out to the Edaljis′ was the deep animosity Captain Anson had against the immigrant Edalji family. There is some evidence that Anson kept up his tirade believing that Edalji was complicit, based on inputs from George′s brother Horace. Horace in turn was ridiculed by the Edalji family, who closed their ranks around George, following which Horace left the area, changed his last name and lived an obscure life as a tax inspector.

Elizabeth Foster died in 1905 and Conan Doyle passed away in 1930, never managing to obtain complete justice and closure for his client, complaining bitterly even in his late years on the ineptness of the police and the Home office staff. But he had managed to get something even more important done, for it was due partly to his efforts and the Edalji case that the British Criminal Court of Appeals was set up in 1907.

In 1934, a person named Enoch Knowles was finally caught and convicted of the letter writing crimes. George Edalji, then 44, tried again to obtain compensation for his three years of wrongful jail confinement, but the Home office did not relent. George Edalji trundled on, with his work, living with his sister Maud, finally passing away in 1953 (Horace in 1952, Maud in 1961). None of the three Edalji offspring ever returned to Staffordshire.

The Great Wyrley cattle maiming mystery, however, remains unsolved.

| 1. | Weaver G. Conan Doyle and the Parson's son: The Edalji case. England:Vanguard Press; 2006:21. England:Vanguard Press; 2006:21.'>[Google Scholar] |

| 2. | Weaver G. Conan Doyle and the Parson's son: The Edalji case. England:Vanguard Press; 2006:25-27, 31. England:Vanguard Press; 2006:25-27, 31.'>[Google Scholar] |

| 3. | Weaver G. Conan Doyle and the Parson's son: The Edalji case. England:Vanguard Press; 2006:29-31. England:Vanguard Press; 2006:29-31.'>[Google Scholar] |

| 4. | Doyle AC. True crime files--Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. New York:Berkeley Publishing; 2001:33. [Google Scholar] |

| 5. | Doyle AC. True crime files--Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. New York:Berkeley Publishing; 2001:34. [Google Scholar] |

| 6. | Risinger DM. Boxes in boxes: Julian Barnes, Conan Doyle, Sherlock Holmes and the Edalji Case. Int Commentary Evidence 2006; 4(2): Article 3. [Google Scholar] |

| 7. | Weaver G. Conan Doyle and the Parson's son: The Edalji case. England:Vanguard Press; 2006:103,182,183. England:Vanguard Press; 2006:103,182,183.'>[Google Scholar] |

| 8. | Cattle maiming. The Star. Monday, 26 Oct 1903 (column 4). [Google Scholar] |

| 9. | Sarvepalli G. Selected works of Jawaharlal Nehru. Letter dated 18 Jan 1907. Series 1, Vol 1, pp 16, New Delhi:Jawaharlal Memorial Fund; 1984. [Google Scholar] |

| 10. | The Medical Press and Circular, Volume 134, page 55, (Jan 16, 1907, The Edalji Case, letter to editor) [Google Scholar] |

| 11. | Sketch: A journal of art and actuality, 23 Jan 1907; 57: 39. [Google Scholar] |

| 12. | Doyle AC. True crime files--Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. New York:Berkeley Publishing; 2001:92-3. [Google Scholar] |

| 13. | Law Times, the journal and record of the law and lawyers, Report on the Edalji case, 25 May 1907; 123 (3347): 92-3. [Google Scholar] |

| 14. | Weaver G. Conan Doyle and the Parson's son: The Edalji case. England:Vanguard Press; 2006:336. England:Vanguard Press; 2006:336.'>[Google Scholar] |

Fulltext Views

2,696

PDF downloads

2,024