Translate this page into:

Electronic health and medical records for comprehensive primary healthcare in India

2 International Union against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease (The Union), Paris, France and The Union, Southeast Asia, New Delhi, India

3 SRL Limited–Fortis Hospital, Bannerghatta Road, Bangaluru, Karnataka, India

4 All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Ansari Nagar, New Delhi 110029, India

5 Achutha Menon Centre for Health Sciences Studies, Sree Chitra Tirunal Institute for Medical Sciences and Technology, Thiruvananthapuram 689005, India

6 Post Graduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh, India

Corresponding Author:

Hemant Deepak Shewade

International Union against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease (The Union), Paris, France and The Union, Southeast Asia, New Delhi

India

hemantjipmer@gmail.com

| How to cite this article: Mohan N, Shewade HD, Shilpa D M, Lobbo SC, Patil AG, Gupta V, Soman B, Aggarwal AK. Electronic health and medical records for comprehensive primary healthcare in India. Natl Med J India 2019;32:373-374 |

India contributes to 18% of the global population. How India performs in delivering comprehensive primary healthcare (CPHC) will contribute towards the attainment of Sustainable Development Goals 3.7 and 3.8 targets of universal health coverage.[1]

In India, under the National Health Mission (NHM), CPHC is delivered through a medical officer who manages a primary health centre catering to 20 000–30 000 population (50 000–60 000 in an urban setting). With the help of village-level frontline workers, an auxiliary nurse-midwife (ANM) caters to a population of 3000–5000 (10 000 in urban settings).[2] An ANM manages 12–15 data registers and one person's data are recorded into multiple registers. Service indicators are manually generated every month and fed into the electronic health management information system (HMIS).[3],[4]

eHealth applications, which include electronic health/medical records (EHRs/EMRs), have the potential to contribute towards universal health coverage.[5] EHRs involve maintaining digitized health records of individuals belonging to the service area of a health facility. The baseline data for EHRs are individual-level sociodemographic and clinical data collected and updated by the ANM during the annual household survey. CPHC provided to individuals under the NHM can be updated on this EHR platform. EMRs are for patients who visit a health facility to seek services irrespective of whether they belong to the service area or not. The EMRs can also be linked with the EHRs.

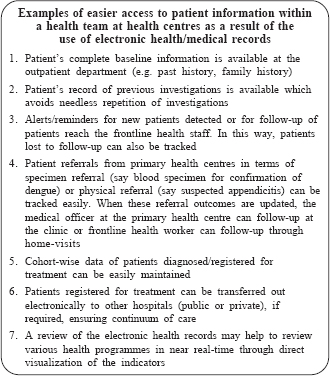

There are many advantages of EHRs/EMRs, one being that the seamless generation of HMIS-related data alleviates the work burden for an ANM. Another being the access to patient information in real time within a health team (Box).[6] EHRs provide a real-time picture of disease burden, which can help in providing better response to disease outbreaks or adjust the focus of service delivery programmes. With the need for integration of long-term care for chronic diseases in the NHM, the development of electronic systems to capture longitudinal data is essential for ensuring continuity and quality of care.

Since 2016, EHRs related to maternal and child health are being generated using tablet-based (mobile hand-held computer device) Anmol (meaning ‘unique’) application in many states of India.[7] The NHM has plans to roll out population-based screening for non-communicable diseases (NCDs), namely diabetes, hypertension, and oral, breast and cervical cancers supported by a tablet-based NCD application in 200 districts.[8] Kerala was the first state to implement a comprehensive eHealth programme that includes EHRs and EMRs.[9] Haryana has developed an EMR for its public health facilities.[10] Aam aadmi Mohalla clinics (‘common man community clinics’) in Delhi use a tablet-based EMR.[11]

To ensure optimal functioning and usage of these EHR/EMR initiatives in India, the following points need to considered.

First, the workload of frontline service providers should not increase as a result of EHRs/EMRs. Multiple, parallel eHealth initiatives may lead to situations where there is one tablet device for each health programme and each application requires repeated entries of baseline data (individual level socio-demographic and clinical data). These can be addressed by (i) doing away with paper-based registers after a pre-defined period of simultaneous data collection in paper-based registers and applications; (ii) considering a comprehensive public health management application where EHR applications of various programmes are built into one application; and (iii) ensuring that the various applications are present in the same tablet and they are interoperable (these parallel applications should be able to ‘talk’ to each other). While ensuring interoperability, patient confidentiality should be maintained and issues related to data ownership addressed. The eHealth applications and databases should be in line with India's EHR standards (2016).[12] The standards include clinical informatics standards, data ownership, privacy and security aspects and the various coding systems. The use of standardized vocabulary such as SNOMED-CT must be mandatory. The data structures of the baseline data must be standardized. India is in the process of formulating its digital information security in healthcare act (DISHA, ‘direction’), which is a step in the right direction.[13]

Second, the EHRs/EMRs should have an option for offline data capture followed by syncing with the cloud as and when the internet is available. Many examples of EHRs mentioned earlier have this option for offline data entry in hand-held tablets. This will ensure that service delivery will not get affected by poor or interruptions in internet either in the health facilities or in the field.

Third, a strong support system is necessary to ensure smooth uptake, provide help and address any concerns about user interface and technical glitches. Periodic operational research around these systems will help in understanding the enablers and barriers and improve the coverage and quality of uptake of EHRs/EMRs.

Finally, the initiatives will not be worthwhile unless the frontline service providers benefit from generating EHRs/EMRs. Regular and timely analysis of data should be ensured at various levels of healthcare starting from where it has been generated, if necessary by hiring expertise from local teaching/ academic institutions.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Department for International Development, UK, for funding the Global Operational Research Fellowship Programme at The Union, Paris, France in which HDS works as a senior operational research fellow.

Authors' contribution: NM, HDS and AGP conceived the idea; NM and HDS prepared the first draft; all authors provided critical comments and approved the final draft.

Conflicts of interest. None declared

| 1. | World Health Organization. Health in 2015 from Millennium Development Goals (MDG) to Sustainable Development Goals (SDG). Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2015. [Google Scholar] |

| 2. | National Health Mission, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. NHM Components: Infrastructure; 2018. Available at http://nhm.gov.in/ nrhm-components/health-systems-strengthening/infrastructure.html (accessed on 25 Jan 2019). [Google Scholar] |

| 3. | Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation, Government of India. Records and Reports Maintained at Sub Health Centre Level. Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation; 2019. Available at www.mospi.gov.in/ 91-records-and-reports-maintained-sub-health-centre-level (accessed on 25 Jan 2019). [Google Scholar] |

| 4. | National Health Mission, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. Health Management Information System. National Health Mission; 2019. Available at https://nrhm-mis.nic.in/SitePages/Home.aspx (accessed on 25 Jan 2019). [Google Scholar] |

| 5. | World Health Organization. Global Diffusion of eHealth: Making Universal Health Coverage Achievable. Report of the Third Global Survey on eHealth. Geneva, Switzerland:WHO Document Production Services; 2017. [Google Scholar] |

| 6. | O'Malley AS, Draper K, Gourevitch R, Cross DA, Scholle SH. Electronic health records and support for primary care teamwork. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2015;22:426–34. [Google Scholar] |

| 7. | Press Information Bureau, Government of India. On World Health Day, Health Minister Launches New Health Initiatives and Mobile Apps. Press Information Bureau; 2016. Available at http://pib.nic.in/newsite/PrintRelease.aspx?relid= 138674 (accessed on 24 Jan 2019). [Google Scholar] |

| 8. | Press Information Bureau, Government of India. Health Ministry Partners with Dell and Tata Trusts to provide Technology Solution for a Nationwide Healthcare Program. Press Information Bureau; 2018. Available at http://pib.nic.in/newsite/ PrintRelease.aspx?relid=183605 (accessed on 24 Jan 2019). [Google Scholar] |

| 9. | Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of Kerala. eHealth and Project. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare; 2019. Available at https:// ehealth.kerala.gov.in/ (accessed on 25 Jan 2019). [Google Scholar] |

| 10. | State Health System Resource Centre, Government of Haryana. Healthcare Technology Division: Advanced Healthcare Made Personal. India:State Health System Resource Centre; 2017. Available at http://hshrc.org.in/e-Upchaar.html (accessed on 24 Jan 2019). [Google Scholar] |

| 11. | Sharma DC. Delhi looks to expand community clinic initiative. Lancet 2016;388:2855. [Google Scholar] |

| 12. | e-Health Division, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. Electronic Health Records (EHR) Standards for India. New Delhi, India:Ministry of Health and Family Welfare; 2016. [Google Scholar] |

| 13. | Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. Comments on Draft Digital Information Security in Health Care Act, (DISHA). Ministry of Health and Family Welfare; 2018. Available at https://mohfw.gov.in/newshighlights/ comments-draft-digital-information-security-health-care-actdisha (accessed on 23 Jan 2019). [Google Scholar] |

Fulltext Views

2,019

PDF downloads

768