Translate this page into:

Exogenous endophthalmitis caused by Enterobacter cloacae following water gun injury

Correspondence to SANDIP SARKAR; drsandip19@gmail.com

[To cite: Deb AK, Neena A, Chowdhury SS, Sarkar S, Suneel S, Gokhale T. Exogenous endophthalmitis caused by Enterobacter cloacae following water gun injury. Natl Med J India 2023;36:367–9. DOI: 10.25259/NMJI_945_20]

Abstract

Enterobacter is a Gram-negative anaerobic bacillus. Enterobacter-associated endophthalmitis is rare. We report Enterobacter cloacae-associated traumatic endophthalmitis following a water gun injury with no visible external entry wound. A 46-year-old man presented with features masquerading as traumatic uveitis in his left eye following injury by water stream from a toy gun. He was started on topical steroids but within 2 days of initial presentation, there was worsening of vision, presence of hypopyon in the anterior chamber and presence of vitreous exudates confirmed on ocular ultrasound B-scan. Endogenous endophthalmitis was ruled out by extensive work-up including sterile urine and blood cultures. Emergency vitrectomy was done along with lensectomy and silicone oil implantation. E. cloacae were isolated from the vitreous sample, which were sensitive to all standard antibiotics tested. Final visual acuity was 20/200. Traumatic endophthalmitis is usually preceded by a penetrating ocular injury in the form of a corneal, limbal or scleral tear with or without choroidal tissue prolapse and vitreous prolapse. A high index of suspicion is, therefore, needed for the diagnosis of endophthalmitis in the absence of corneal injury following water jet trauma to the eye.

INTRODUCTION

Enterobacter is a ‘Gram-negative facultative anaerobic bacillus’. It is found as a commensal in the human gastrointestinal tract and is usually associated with human respiratory and urinary tract infections, sepsis and bone infections. Enterobacter-associated endophthalmitis is a rare occurrence. It has been isolated from rare cases of postoperative, traumatic or endogenous endophthalmitis.1–4

Enterobacter cloacae like other Enterobacter species is also a commensal and is commonly isolated from pharmaceutical products, intravenous fluids, surgical devices, etc. in nosocomial infections. It has been previously reported in a few instances of endophthalmitis with poor visual outcomes.5 We report a E. cloacae-associated traumatic endophthalmitis that occurred secondary to a water gun injury and with no visible external entry wound. Only one case of exogenous endophthalmitis has been reported in the literature secondary to a water gun injury.6 Furthermore, the final visual and anatomical outcomes in our patient were good unlike the other cases of E. cloacae-associated endophthalmitis reported earlier.4,5

THE CASE

A 46-year-old healthy man presented to the emergency ophthalmology services with painful diminution of vision, redness, watering and photophobia in his left eye following accidental injury with a water gun 24 hours ago. On examination, the best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) was 20/20 in the right eye (OD) and 20/40 in the left eye (OS). The left eye had circumciliary congestion, anterior chamber (AC) reaction 3+ cells, flare 2+. The cornea was clear and there was no lid oedema, conjunctival chemosis or hypopyon at initial presentation. Dilated fundus examination of the left eye at presentation revealed mild media haze due to AC reaction with an otherwise normal fundus with no evidence of vitritis or retinal exudates. The right eye examination was within normal limits. Intraocular pressures were 16 mmHg in OS and 10 mmHg in OD. Based on the history and clinical examination, a provisional diagnosis of OS traumatic uveitis was made. He was started on hourly 1% prednisolone acetate eye drops, 2% homatropine eye drops twice daily along with prophylactic moxifloxacin 0.5% eye drops four times a day. The patient was advised to come for a review in the outpatient department (OPD) on the following day. However, he failed to come for a review in the OPD on the following day and presented 2 days later with worsening of symptoms.

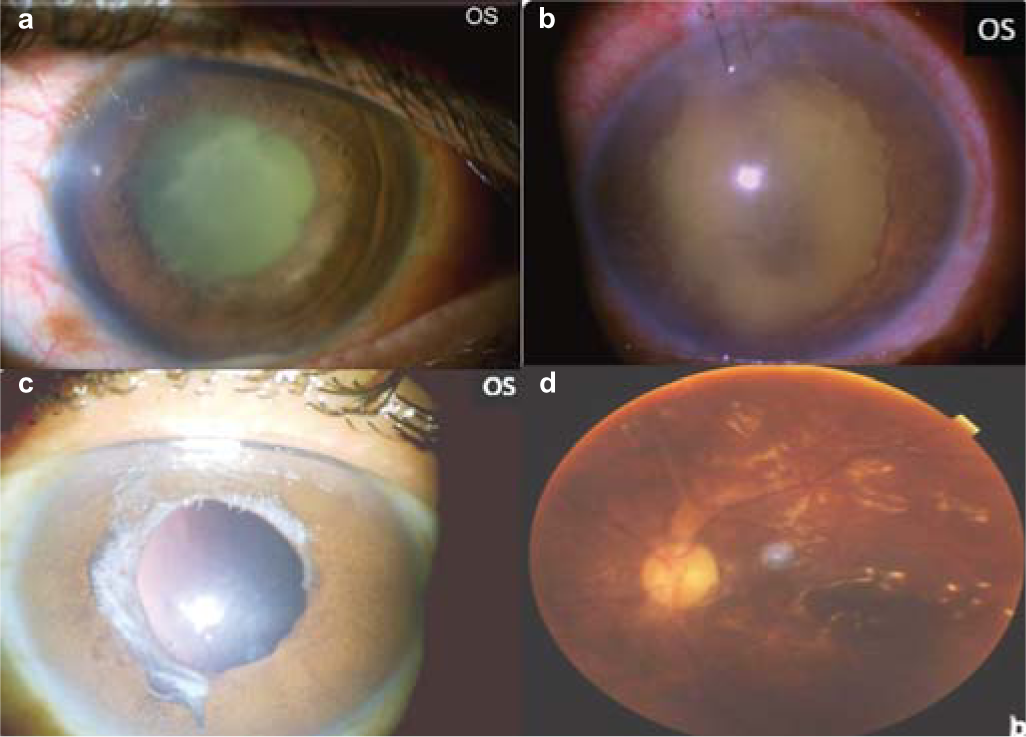

On examination, BCVA in OS had decreased to hand movements. Slit-lamp examination of the left eye showed non-mobile hypopyon (1 mm), dense fibrinous membrane in AC covering the pupil and obscuring the view of the fundus (Fig. 1a). He had associated mild lid oedema. B-scan ultrasonography (USG) revealed mild-to-moderate vitreous echogenicity suggestive of endophthalmitis. Considering the clinical features at the follow-up visit and dramatic worsening of symptoms, the diagnosis was revised to endophthalmitis. The patient underwent emergency pars plana vitrectomy, lensectomy and silicone oil endotamponade. Lensectomy was done as multiple small foci of lenticular abscess were noted intraoperatively after removal of the dense fibrinous membrane overlying the lens. Silicone oil was injected to prevent the growth of the organism in the vitreous cavity. Intravitreal injections of 1 mg/0.1 ml vancomycin and 2.25 mg/0.1 ml ceftazidime were given at the end of the surgery. Postoperatively, the patient was treated with topical 0.5% moxifloxacin hourly, 1% atropine eye drops thrice daily and oral ciprofloxacin 750 mg twice daily.

- Slit-lamp images showing (a) dense fibrinous membrane over the lens and hypopyon at presentation; (b) contracting fibrinous membrane over the pupillary area at day 7 after surgery; (c) at 1 month after surgery, slit-lamp image showing aphakia and quiet anterior chamber; and (d) fundus image showing silicone oil-filled globe with normal disc and macula

Vitreous sample was sent for microbiological examination. Gram-stain showed Gram-negative bacilli and after 48 hours of incubation, the culture showed pink, lactose-fermenting mucoid colonies suggestive of E. cloacae, which was further confirmed by Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption Ionisation Time-of-Flight technology-VITEK® MS (BioMérieux, France). Antimicrobial sensitivity showed the isolates to be sensitive to amikacin, cefoperazone/sulbactam, ceftazidime, ceftriaxone, ciprofloxacin, meropenem and piperacillin/tazobactam. Based on the culture sensitivity report, fortified ceftazidime 5% eye drops hourly and intravenous meropenem (1 g three times a day for 7 days) were added.

He had a past history of pulmonary tuberculosis, for which he had received antitubercular treatment 2 years ago. A complete work-up was done to rule out endogenous endophthalmitis, but no primary focus of infection could be found. Blood culture and urine culture were sterile. A pulmonology opinion ruled out any active focus of pulmonary tuberculosis. The patient was kept under observation for close monitoring. He was afebrile at the onset of symptoms as well as during the hospital stay. During the initial postoperative period, the AC was full of inflammatory exudates with no view of the fundus (Fig. 1b). Over time, the vitreous cavity and anterior segment cleared, and vision improved to 20/400 at 1 month postoperatively (Figs 1c and d). Once the media cleared, a temporal retinal break was noted during fundus evaluation for which barrage laser was performed with laser indirect ophthalmoscopy. After 3 months of follow-up, the patient had uncorrected visual acuity of 20/400 and BCVA of 20/200.

DISCUSSION

Our patient had traumatic endophthalmitis caused by E. cloacae due to a high-velocity water jet. Only one case of traumatic endophthalmitis secondary to water gun injury has been reported in the literature.6 Pressurized water streams generated in toy water guns or any other water jet may cause serious ocular injury and raised intraocular pressures, especially at water velocities >8.5 m/second.7 Traumatic uveitis due to the pressure impact akin to blunt ocular trauma is a plausible diagnosis in such instances. In our patient too the absence of an obvious corneoscleral injury mark or entry wound, absence of any localized corneal oedema and a fairly good VA (20/40) with only minimal media haze due to associated AC reaction at the time of initial presentation posed a diagnostic challenge. Traumatic uveitis was the initial diagnosis based on the history and clinical presentation. However, the patient showed a rapid deterioration of clinical features and presented with dense vitritis, thick fibrinous membrane in AC and hypopyon within the next 2 days. Endophthalmitis was confirmed based on the clinical features and USG B-scan. The differential aetiological diagnosis at this point was endogenous endophthalmitis or ocular commensal-induced endophthalmitis. However, extensive search for a primary focus could not localize an infection elsewhere. The only possible source of endophthalmitis was water jet trauma. Temporal association between the ocular trauma and the onset of endophthalmitis in the absence of any other identifiable endogenous foci established this as traumatic endophthalmitis.

In the report by Berenger et al., the child had presented with corneal clouding and conjunctival injection following injury with water stream from a toy gun.6 On the contrary, our patient had a clear cornea with only AC reaction at the time of initial presentation. A high index of suspicion and close follow-up is, therefore, needed in case of water jet injury without any visible corneal injury to diagnose traumatic endophthalmitis at the earliest and institute appropriate treatment. While Enterobacters are not typically isolated from water sources, they can be found in the soil.1 We conjecture that the tap water or the toy gun may have been contaminated with Enterobacter from the soil.

Early vitrectomy is an integral component of the management of any severe form of postoperative endophthalmitis— endogenous or exogenous. It has a positive bearing on the final visual and anatomical outcomes as it facilitates the reduction of inflammatory and bacterial load along with clearance of the cellular debris.6 In our patient, vitrectomy was performed in an acceptable time-frame of 72 hours despite an initial unclear diagnosis. Silicone oil implant in endophthalmitis can act as a physical barrier and prevent further multiplication of the microorganism in the residual vitreous following vitrectomy.8

Enterobacter species are most susceptible to ciprofloxacin, amikacin and ceftazidime.1,2 Singh et al. reported a case of post-traumatic Enterobacter endophthalmitis where the isolates were resistant to vancomycin, amikacin, second-generation cephalosporins and fluoroquinolones. The patient was treated successfully with intravitreal piperacillin–tazobactam injection.9 Similarly, Dave et al.1 and Pathengay et al.2 reported Enterobacter endophthalmitis resistant to aminoglycosides, cephalosporins, fluoroquinolones and chloramphenicol.1,2 They were treated with either intravitreal colistin or intravitreal tazobactam–piperacillin. Bhat et al. reported 7 patients with multidrug-resistant (MDR) Enterobacter endophthalmitis showing resistance to vancomycin, amikacin, quinolones, cephalosporins and chloramphenicol and susceptibility to imipenem and piperacillin–tazobactam.10 Eyes with favourable visual outcomes in these studies ranged from 20% to 25%. However, few patients with MDR in these studies progressed to phthisis bulbi and pan ophthalmitis.1,2,9,10 In contrast to these reports, E. cloacae in our patient was sensitive to all the antibiotics tested. This favourable antibiotic susceptibility combined with an early vitrectomy and silicone oil implantation possibly led to a good anatomical and visual outcome.

In summary, traumatic endophthalmitis is usually preceded by a penetrating ocular injury in the form of a corneal, limbal or scleral tear with or without choroidal tissue prolapse and vitreous prolapse. A high index of suspicion is, therefore, needed for the diagnosis of endophthalmitis in the absence of corneal injury following water jet trauma to the eye. Traumatic uveitis and endogenous endophthalmitis are possible differential diagnoses that should be ruled out in such patients.

Conflicts of interest

None declared

References

- Enterobacter endophthalmitis: Clinical settings, susceptibility profile, and management outcomes across two decades. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2020;68:112-17.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enterobacter endophthalmitis: Clinicomicrobiologic profile and outcomes. Retina. 2012;32:558-62.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enterobacter cloacae endophthalmitis: Report of four cases. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:48-51.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enterobacter cloacae postsurgical endophthalmitis: Report of a positive outcome. Case Rep Ophthalmol. 2013;4:42-5.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Exogenous endophthalmitis caused by Enterococcus casseliflavus A case report and discussion regarding treatment of intraocular infection with vancomycin-resistant enterococci. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol. 2015;26:330-2.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eye injury risk from water stream impact: Biomechanically based design parameters for water toy and park design. Curr Eye Res. 2012;37:279-85.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Postoperative endophthalmitis due to Burkholderia cepacia complex from contaminated anaesthetic eye drops. Br J Ophthalmol. 2014;98:1498-502.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enterobacter endophthalmitis: Treatment with intravitreal tazobactam-piperacillin. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2007;55:482-3.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Outbreak of multidrug-resistant acute postoperative endophthalmitis due to Enterobacter aerogenes. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2014;22:121-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]