Translate this page into:

Haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis associated with liver injury in systemic sarcoidosis

Correspondence to BIDYUT KUMAR DAS; bidyutdas@hotmail.com

[To cite: Tripathy SR, Anirvan P, Parida MK, Meher D, Bharali P, Gogoi M, et al. Haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis associated with liver injury in systemic sarcoidosis. Natl Med J India 2023;36:312–14. DOI: 10.25259/NMJI_MS_314_21]

Abstract

Hepatic involvement in sarcoidosis, though common, is usually asymptomatic. Hepatomegaly and deranged liver function tests are the usual manifestations. However, unexplained hepatomegaly in sarcoidosis not responding to immunosuppressive therapy could indicate an alternative pathology. Haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH), although seldom reported in sarcoidosis, can cause hepatosplenomegaly and cytopenias. HLH occurring concomitantly with hepatic sarcoidosis is extremely rare. We report a patient of systemic sarcoidosis who presented with fever, hepatosplenomegaly and jaundice despite being on steroid therapy. He was subsequently diagnosed with HLH. The clinical response to treatment with pulse steroid and oral cyclosporine was dramatic.

INTRODUCTION

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem disease with pulmonary involvement in the majority of cases. Hepatic involvement in sarcoidosis is usually asymptomatic. However, hepatomegaly is evident clinically in 20% of cases and in 40% of cases on radiological examination.1 Abnormal liver functions are present in 20%–40% of patients.2 Jaundice occurs in <5% of patients.3,4 Haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) is an unregulated and exaggerated immune response involving the engulfment of haematopoietic cells by activated macrophages. Primary HLH occurs due to specific genetic abnormalities while secondary or acquired HLH can occur in conditions such as infections, autoimmune/rheumatological disorders, malignancies and metabolic abnormalities. HLH is characterized by fever, hepatosplenomegaly, cytopenias, hepatic and central nervous system dysfunction and the presence of haemophagocytosis in the bone marrow and other lymphoid organs. The presence of either hepatomegaly or splenomegaly in combination with fever and jaundice has been observed in around 50% of patients.5 However, HLH occurring in the setting of sarcoidosis is uncommon while HLH complicating hepatic sarcoidosis has seldom been reported in the literature.6

THE CASE

A 24-year-old man undergoing treatment for cutaneous sarcoidosis with periorbital and parotid involvement (histopathology proven) diagnosed 10 months prior was referred for evaluation of hepatomegaly and jaundice. Tuberculosis had been ruled out and his cutaneous nodules, periorbital and parotid swellings had disappeared on the institution of steroid therapy. He had been put on tapered dose of steroids and was doing apparently well. His baseline liver function tests showed mild elevation of transaminases without any hyperbilirubinaemia (aspartate aminotransferase [AST] 79 i.u./L; alanine aminotransferase [ALT] 90 i.u./L). However, he started developing fever, vague abdominal discomfort and jaundice after 6 months of treatment. Fever was continuous while jaundice was non-fluctuating. On evaluation in the department of gastroenterology, he was found to be febrile, icteric, tachypnoeic and had tachycardia. Abdominal examination revealed splenomegaly and non-tender hepatomegaly with firm, sharp and regular margins with a liver span of 18 cm. Ultrasound examination confirmed hepatomegaly with grade 2 fatty changes, splenomegaly and mild ascites. Leucopenia was present (3000/cmm) and liver function tests were deranged (total bilirubin 7.2 mg/dl, direct bilirubin 6.0 mg/dl, AST 418 i.u. /L (<35 i.u. /L), ALT 260 i.u. /L (<45 i.u./L), alkaline phosphatase 1201 i.u./L (<369 i.u./L), gamma-glutamyl transferase 390 i.u./L (<60 i.u./L). A provisional diagnosis of hepatic sarcoidosis was entertained after excluding other causes of hepatitis. However, the appearance of fever, hepatomegaly and jaundice, despite the resolution of cutaneous nodules, periorbital and parotid swellings pointed to an alternative pathophysiological possibility.

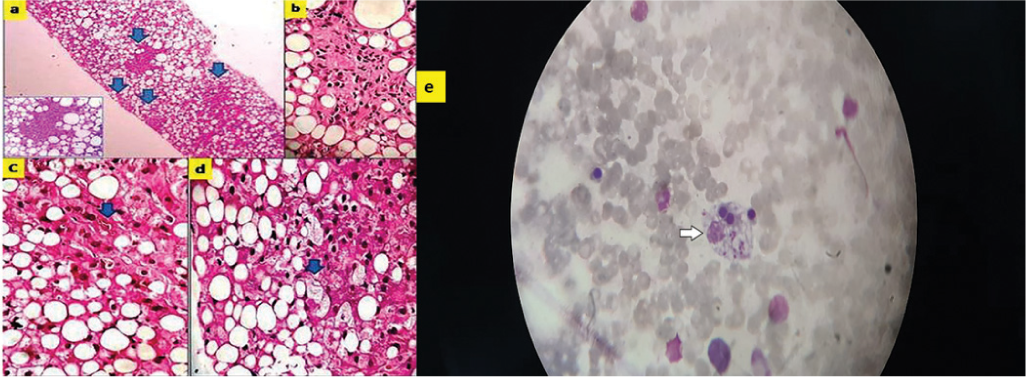

Investigations did not reveal any infective aetiology. Blood cultures were negative. Rapid antigen test and reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction for SARS CoV-2, serology for hepatitis A and E and antinuclear antibody (ANA) were negative. Serologies for Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) and cytomegalovirus (CMV) were negative. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography showed hepatosplenomegaly without biliary obstruction. A liver biopsy showed preserved liver architecture while portal tracts showed epithelioid cell collections forming non-caseating granuloma. Eosinophils and plasma cells were found in one granuloma. Canalicular and hepatocytic cholestasis was noted along with features of feathery degeneration. Macrovesicular steatosis was seen in more than 60% of the liver parenchyma, which was interspersed by focal inflammation and ballooned hepatocytes. Scattered Kupffer cell hyperplasia in sinusoids was also evident (Fig. 1). The presence of non-caseating granulomas and intrahepatic cholestasis supported the diagnosis of hepatic sarcoidosis. However, the presence of extensive macrovesicular steatosis could not be explained.

- Photomicrograph on the left panel shows (a) focal lesions in portal areas (arrows) ×100. Inset of focal lesions shows noncaseating granuloma; (b) granuloma contains eosinophils and plasma cells ×400; (c) canalicular cholestasis (arrow) ×100; (d) steatohepatitis with ballooned hepatocytes (arrow) ×100; (e) photomicrograph on the right panel showing a single macrophage engulfing nucleated red blood cells (arrow) ×100

During hospital stay, he developed spikes of fever (106 °F) which did not respond to antipyretics. Repeat examination of blood counts showed bicytopenia (total leucocyte count 2200/cmm, platelets 42 000/cmm), erythrocyte sedimentation rate 5 mm at the end of 1st hour and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein 38 mg/L (<6 mg/L) with hyponatraemia (128 mEq/L). Additional investigations showed elevated ferritin (>2000 ng/L), decreased serum fibrinogen (73 mg/dl) and elevated triglycerides (1463 mg/dl). A bone marrow aspiration showed the presence of haemophagocytosis (Fig. 1). A diagnosis of secondary HLH was made based on HLH-2004 criteria as well as the H-score. The patient was pulsed with intravenous methylprednisolone 1 g for 3 days and his fever subsided. Oral cyclosporine, 2 mg/kg, was started with close monitoring of the liver function. He continued to be afebrile and his cytopenia improved. His bilirubin and liver enzymes decreased. Post-treatment, his bilirubin level normalized while AST and ALT decreased to 44 and 60 i.u./L, respectively. He was discharged in a stable condition.

DISCUSSION

Hepatic sarcoidosis has a spectrum of manifestations ranging from asymptomatic elevation of transaminases, jaundice and hepatomegaly to rarely cirrhosis and liver failure. Apart from the biochemical abnormalities, radiological investigations can help in reaching a diagnosis. The presence of multiple hepatic nodules may be indicative of hepatic sarcoidosis. Liver biopsy provides clinching evidence of hepatic sarcoidosis. We did a liver biopsy in our patient since a definite diagnosis could not be reached after biochemical, serological and radiological investigations. Non-caseating and epithelioid granulomas are usually found in periportal and portal areas in hepatic sarcoidosis.7 There were similar histological changes in the liver biopsy of our patient.

Secondary HLH can be triggered by infections: Bacterial, viral, protozoal, fungal, haematological and nonhaematological malignancies, and autoimmune diseases. Defective cytotoxic T-cell function along with overexpression of macrophage activity precipitates HLH. HLH is characterized by fever, hepatosplenomegaly, cytopenias, hypertriglyceridaemia, elevated ferritin, hypofibrinogenaemia, elevated soluble CD25, transaminitis, hyperbilirubinaemia and cerebrospinal fluid pleocytosis. HLH is a life-threatening condition and early recognition and prompt initiation of treatment are the cornerstones of management. The diagnosis of HLH is based on the HLH-2004 criteria.8–10 The H-score has also been evaluated for the diagnosis of HLH in both adults and children.8 Liver biopsy in HLH rarely shows signs of haemophagocytosis probably due to late involvement of the liver in the disease process.11 While cholestasis and steatosis occur frequently, sinusoidal haemophagocytosis is an occasional finding and is considered non-specific for HLH.12 In 50% of patients, liver biopsy findings suggest the underlying condition that triggers HLH.5

Sarcoidosis triggering HLH is rare with less than a dozen reported cases in the medical literature.13 Infectious aetiologies known to precipitate secondary HLH such as EBV, CMV, dengue, hepatitis A, B, C and E, HIV, tuberculosis, leptospirosis, scrub typhus, malaria and malignancies were ruled out in our patient, establishing underlying sarcoidosis as the most plausible trigger. The case is unique as our patient had hepatic sarcoidosis along with HLH, which made the diagnosis difficult. This is a rare finding and to our knowledge, there is only one previous published case report.6 Liver dysfunction is common in HLH and hepatomegaly may occur in 50% of patients. Cholestasis and macrovesicular steatosis are frequent histopathological findings on liver biopsy.14,15 The absence of haemophagocytic activity in the liver is also compatible with the diagnosis of HLH.12 We presume that the low-dose steroids that the patient was consuming may have delayed the onset of manifest HLH. The previous case report on HLH in hepatic sarcoidosis also describes an identical scenario where the diagnosis was delayed due to steroid treatment.6

It is important to remember that hepatomegaly in sarcoidosis may not always be due to hepatic infiltration. Organomegaly along with cytopenia in sarcoidosis should raise a suspicion of underlying HLH. The combination of hepatic sarcoidosis and HLH is extremely difficult to diagnose. A prompt diagnosis and early initiation of therapy may be life-saving.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Dr Rajib Kumar Nayak for help in interpretation of the bone marrow aspiration.

Conflicts of interest

None declared

References

- Liver-test abnormalities in sarcoidosis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;24:17-24.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Disseminated sarcoidosis presenting as granulomatous gastritis: A clinical review of the gastrointestinal and hepatic manifestations of sarcoidosis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2012;46:367-74.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hepatic manifestations of hemophagocytic syndrome: A study of 30 cases. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:852-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A rare case of hepatic sarcoidosis leading to the development of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113:S1310.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Performances of the H-Score for diagnosis of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in adult and pediatric patients. Am J Clin Pathol. 2016;145:862-70.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Consensus recommendations for the diagnosis and management of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis associated with malignancies. Haematologica. 2015;100:997-1004.

- [Google Scholar]

- HLH-2004: Diagnostic and therapeutic guidelines for hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2007;48:124-31.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hepatic sinusoidal hemophagocytosis with and without hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0226899.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Autopsy findings in 27 children with haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Histopathology. 1998;32:310-16.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis complicating systemic sarcoidosis. Cureus. 2018;10:e2838.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Macrovesicular hepatic steatosis revealing pregnancy hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Rev Med Interne. 2015;36:555-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hepatic involvement in hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis In: Hepatitis A and other associated hepatobiliary diseases. London, UK: IntechOpen; 2019.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]