Translate this page into:

Medical students’ perception of the educational environment in a tertiary care teaching hospital in India

2 Department of Preventive and Social Medicine, Jawaharlal Institute of Postgraduate Medical Education and Research, Puducherry, India

Corresponding Author:

Anandhi Amaranathan

12 New Street, Shanthi Nagar, Lawspet, Puducherry 605008

India

anandhiramesh76@yahoo.in

| How to cite this article: Amaranathan A, Dharanipragada K, Lakshminarayanan S. Medical students’ perception of the educational environment in a tertiary care teaching hospital in India. Natl Med J India 2018;31:231-236 |

Abstract

Background. The educational environment perceived by students has an impact on satisfaction with the course of study and academic achievement. We aimed to analyse the perceptions of medical students about their learning environment and to provide feedback to stakeholders involved in curriculum planning and execution.Methods. We did a cross-sectional descriptive study at Jawaharlal Institute of Postgraduate Medical Education and Research, Puducherry using the Dundee Ready Educational Environment Measure (DREEM) questionnaire. The DREEM inventory was administered to the undergraduate students of all semesters (n = 452). Students’ perceptions of learning, perception about teachers, academic self-perceptions, perceptions of atmosphere and their social self-perceptions were measured. The scores obtained were expressed as mean (standard deviation) and analysed using t-test and 1-way ANOVA (with post-hoc comparison using Tukey test). The difference between semesters and gender was also analysed.

Results. The mean (SD) global score was 122.06 (22.27), out of a maximum possible score of 200. Our students opined that teachers were knowledgeable, with this component scoring the maximum of 3.32 and, at the same time, they felt that teaching overemphasizes factual learning (1.41). Only 6 items scored <2. ‘Students’ perception of atmosphere’ scored high among other domains (30 of 48, 62.5%). The mean global score of preclinical students (125.35 [20.43]) was better than clinical students (119.13 [23.44]; p = 0.003).

Conclusion. Although the global score is more positive, we identified a few areas of concern such as overemphasis on factual learning, authoritarian teachers, the not-so-helpful existing learning strategies, vast curriculum (inability to memorize all), lack of supporting system for stressed out students and the boredom they felt in the course. These vital areas should be addressed by the stakeholders for the betterment of learning in the institute.

Introduction

The aim of any learning activity is to impart quality knowledge to learners in the best possible environment. Several factors affect the learning process of any learner. Among them, the learning environment is vital. The way the learner perceives the learning environment has a big impact on the learning. This may help in planning and improving the curriculum and other factors affecting the learning environment.

It is well-known that the educational environment perceived by students has an impact on satisfaction with the course of study, perceived well-being, behavioural aspirations and academic achievement.

There are numerous subtle elements in the learning experience of students for which they may respond variably. If we can identify the elements operating in the educational environment or atmosphere of a given institution or course, and evaluate how they are perceived by students and teachers, we can modify them to enhance the learning experience in relation to our teaching goals.[1] A conducive learning environment is essential for successful training. The environment, as perceived, may be designated as atmosphere. It has been argued that the atmosphere is the soul and spirit of the medical school environment and curriculum. Students’ experiences of the atmosphere of their medical education environment are related to their achievements, satisfaction and success.[2]

We analysed the perceptions of medical students of Jawaharlal Institute of Postgraduate Medical Education and Research (JIPMER), Puducherry, a tertiary care teaching hospital, about their learning environment, which can provide feedback to stakeholders involved in the planning and execution of the curriculum.

Methods

Study design and setting

JIPMER is a tertiary care teaching hospital, well known for its undergraduate and postgraduate medical courses along with nursing and allied medical science courses. It is an institute of national importance under the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India, and was established by the French Government in 1956. We enrol 150 students a year for MBBS from all over India by a common entrance examination. Hence, the student population is from varied cultural and economic backgrounds. We follow the traditional discipline-based curricula in which the MBBS course spans 5½ years and is divided into preclinical (anatomy, biochemistry, physiology), paraclinical (pathology, microbiology, pharmacology, forensic medicine, social and preventive medicine) and clinical phases (ophthalmology, otorhinolaryngology, medicine, surgery, obstetrics) followed by a 1-year compulsory rotating internship. The main part of the curriculum consists of lectures, tutorials and practical classes with a limited number of problem-based sessions.

We conducted a cross-sectional questionnaire-based, descriptive study in 2016, after obtaining permission from the institute’s ethics committee. Written informed consent was obtained from all the participants. Anonymity was ensured.

Sample size

We included students from all semesters except those in the first semester who were fresh to the institution having <6 months’ experience in the medical school. Of 610 students, 485 participated in the study (80%).

Study instrument

We used the Dundee Ready Education Environment Measure (DREEM) questionnaire. Roff et al. developed the 50-item DREEM using a standard methodology based on grounded theory and a Delphi panel of nearly 100 health profession educators from around the world[3] and validated by over 1000 students in countries as diverse as Scotland, Argentina, Bangladesh and Ethiopia to measure and ‘diagnose’ undergraduate educational atmosphere in the health professions. Utilizing a combination of quantitative and qualitative techniques, the methodology was designed to develop a non-culturally specific instrument.[4] DREEM gives a global score (out of 200) for the 50 items and has 5 subscales relating to students’ perceptions of learning (POL, 12 items, maximum score 48), perceptions of teachers (POTs, 11 items, maximum score 44), academic self-perceptions (ASPs, 8 items, maximum score 32), perceptions of atmosphere (POA, 12 items, maximum score 48) and social self-perceptions (SSPs, 7 items, maximum score 28). It has a consistently high reliability and data can be collected and analysed according to variables such as year of study, ethnicity, gender, age and courses/attachments.[4]

Each item is rated on a 5-point Likert scale from 0 to 4 where 0 is strongly disagree and 4 is strongly agree. There are 9 negative items (items 4, 8, 9, 17, 25, 35, 39, 48 and 50), for which correction is made by reversing the scores; thus after correction, higher scores indicate disagreement with that item. Items with a mean score of ≥3.5 are true positive points and those with a mean of ≤2.0 are problem areas; scores in between these 2 limits indicate aspects of the environment that could be enhanced. The maximal global score for the questionnaire is 200, and the global score is interpreted as follows: 0–50 very poor, 51–100 many problems, 101– 150 more positive than negative and 151–200 excellent.[2]

Along with responses to this questionnaire, basic demographic data such as age, gender and semester of study were noted.

Statistical analysis

Scores for each domain and item were expressed as mean (SD). The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was applied to assess the normality of distribution of the DREEM scores. Independent samples t-test and 1-way ANOVA (with post-hoc comparison using Tukey) were used to identify the significance between subgroups. Data were analysed using SPSS software version 20. A value of p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

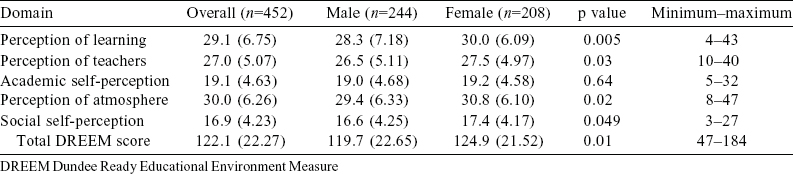

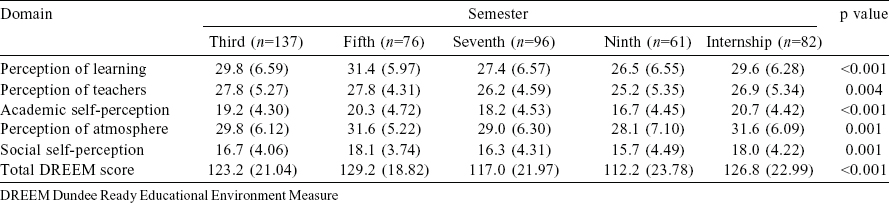

Of 610 students, 485 participated in the study (80%). Of these, we received 452 complete responses (93%). The mean (SD) age of the participants was 20.8 (1.82) years. Among the students 137 were from the third semester, 76 from the fifth semester, 96 from the seventh semester, 61 from the ninth semester and 82 interns. The mean (SD) global score for the DREEM inventory was 122.1 (22.27) of a maximum score of 200. There was a higher mean value for overall perception among female compared with male students and the difference was significant [Table - 1].

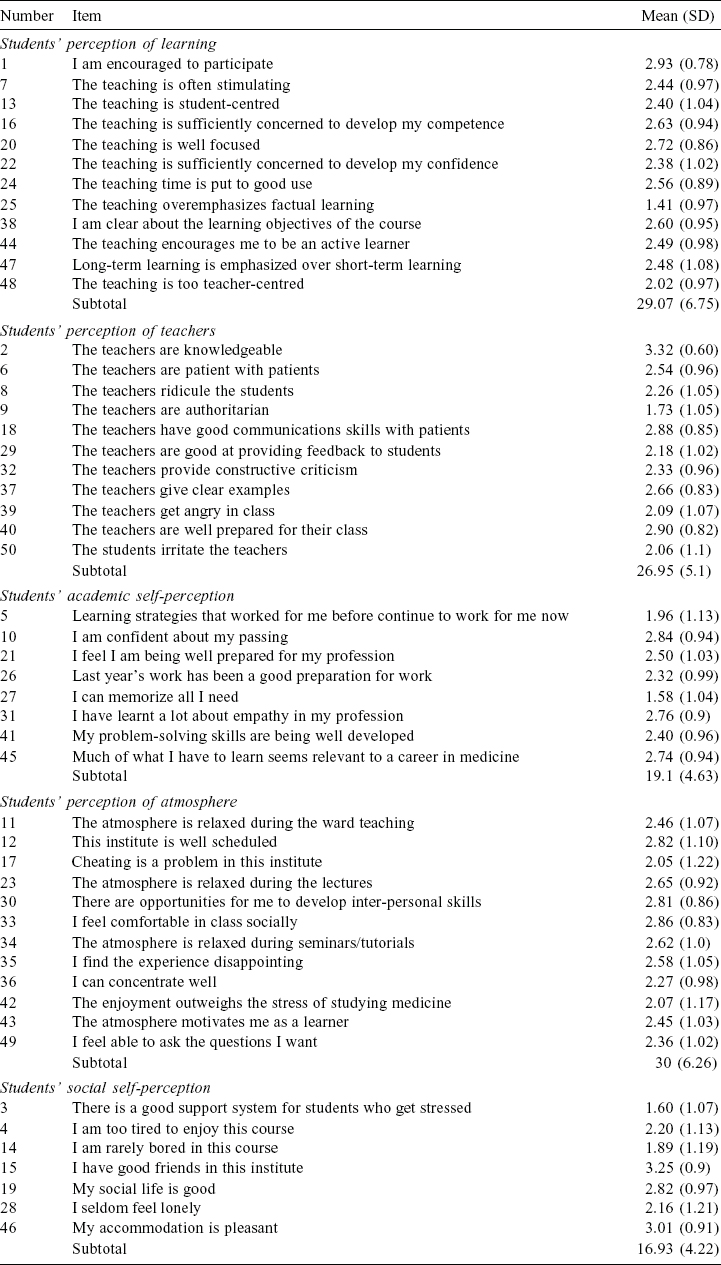

Among the individual item scores [Table - 2], the maximum score (3.32) was for ‘the teachers are knowledgeable’ and the minimum score (1.41) was for ‘the teaching overemphasizes factual learning’. Only six items scored <2. These items were ‘the teaching overemphasizes factual learning’, ‘the teachers are authoritarian’, ‘learning strategies that worked for me before continue to work for me now’, ‘I am able to memorize all I need’, ‘there is a good support system for students who get stressed’ and ‘I am rarely bored in this course’. Three items scored more positively with a mean score of >3, and were ‘the teachers are knowledgeable’, ‘I have good friends in this institute’ and ‘my accommodation is pleasant’.

Among the domains ‘Students’ POA’ scored higher than the other domains (30 of 48). The domain scores for the whole group were compared on a percentage basis because of the different maximum scores of each domain. The highest percentage score was for ‘POA’ (62.5%) and the lowest for ‘ASP’ (59.7%).

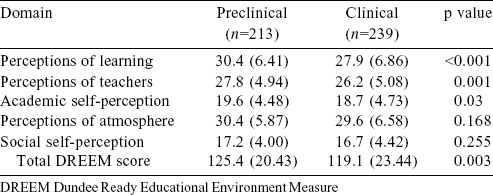

The whole group was divided into preclinical (third and fifth semesters) and clinical batches (seventh, ninth semesters and interns) for analysis. The mean (SD) global score for clinical students 119.1 (23.44) was less than the preclinical students’ score of 125.4 (20.43; p=0.003; [Table - 3].

Discussion

A medical school is an environment in which students are expected to experience various learning activities. The learning environment is the most important determinant of the behaviour of all the parties of education. Thus, it is expected that any curriculum change should involve changes in educational environment, management and organization to result in predicted behavioural changes.[4],[5] Understanding the atmosphere of an institution and its prime determinants will help us in many aspects to understand and improve the curriculum. Though we are ranked among the top 5 medical institutes in India, so far, there is no study which quantitatively assesses our strengths and weaknesses. This is important for any institution to improve.

Successful management of an educational institute is possible with systematic feedback and assessments and continuous measures to improve the lacunae. The DREEM has been used by many institutions across the world[6],[7],[8],[9],[10],[11],[12],[13],[14] to identify the strengths and limitations of the curricular contents, teaching style and the educational atmosphere, which are the main factors in determining the students’ performance and knowledge gain.

The global score for our institution was 122.06 (22.27), which is in the positive range for overall students’ perception about their institute. This is a better score compared to other institutions in India which follow the traditional way of teaching; 101.23 in University College of Medical Sciences and GTB Hospital, University of Delhi, India;[15] 107.44 in Kasturba Medical College, India[16] and 117 in Melaka Manipal Medical College (Manipal Campus), Manipal, Karnataka, India.[12] Some of the universities which follow innovative, student-centred, problem-based learning (PBL) curriculum showed relatively high total score, as in Dundee University, the UK (global score is 13 9),[17] Liverpool Medical School, the UK (133),[18] Lund University, Sweden (144)[19] and Xavier University School of Medicine, the Netherlands (131.79).[10] Contrary to the concern expressed by Roff about the traditional curriculum scoring <120/200,[4] our institute has scored >120 similar to other Indian institutes.[20] In a study conducted in Ankara University, Turkey, despite the student-centred, integrated, problem-based curriculum, they have noticed a lower global DREEM score of 117.63.[21]

The domain score percentage for the whole batch is found to be satisfactory and shows scope for improvement, as they fall under positive than negative category. The domain score percentages are >60 for all the domains—students’ POL (60.6%), POTs (61.3%), ASPs (59.7%), POA (62.5%) and SSPs (60.5%).

Female students (124.88 [21.52]) showed a more positive perception of educational atmosphere in each domain and the overall mean score than male students (119.66 [22.65]). Except in ‘ASP’, all other domains showed a significant difference with female perception being more positive. This has been observed in other similar studies as well.[22],[23] This difference may be due to the different learning styles of females,[24] hard working nature and, in general, a positive attitude towards education. In his book, Fleming[25] mentioned that there are different learning strategies for male and female genders. He mentions that males have a more kinaesthetic response and females have a more ‘read and write’ response, which is also mentioned by Kharb et at.[26]

The mean global score of the preclinical students (125.35 [20.43]) is significantly better than that of clinical students (119.13 [23.44]). Among the 5 domains, perception of learning, perception of teachers and ASP showed statistically significant difference between the two groups—preclinical students scored better than clinical students, which is similar to few other studies.[27],[28] This difference may be due to the overburdening vast curriculum for clinical students and overemphasizing the factual learning method by the traditional method of teaching.

Students’ perception of learning

Overall, the perception of learning falls in the range of scores 2-3, which is better than many other studies which noted a score of <2.[7],[12],[15],[21],[29],[30] The highest scored item in this domain was ‘I am encouraged to participate’. Only one item was reported to score <2—‘the teaching overemphasizes factual learning’. Factual learning is a problem perceived by most institutions with traditional curriculum. A problem-based approach for teaching and evaluation may be a solution.[7],[15],[29]

Females perceive the learning environment to be significantly better (30.03 [6.09]) than males (28.25 [7.18]). Students of the ninth semester (final clinical year) recorded the highest difficulty (26.52 [6.55]) as opposed to those of the fifth semester (31.41 [5.97]; p<0.001). For the clinical year students, most of their learning shifts from ‘comfortable’ classroom teaching to bedside clinical teaching with increase in curriculum content. As mentioned by Kohli and Dhaliwal,[15] bedside teaching is the effective way of teaching clinical problem-solving, communication skills with the patients, ethics and empathy. However, from the obtained scores, it is clear that the way we have structured our teaching sessions is not perceived well by the students. Clinical cases are discussed on the basis of the availability of patients on that day in outpatient clinic. This leads to unpreparedness for the class by the students, which may be the reason for ineffective learning and negative perception of teaching. In addition, space constraints in the outpatient clinic, overburdened consultants with too many patients to treat and time constraints may be the other reasons that cannot be ignored. A similar trend of clinical batch scoring less than the preclinical batch is observed in many other studies.[15],[27] This problem can be addressed by pre-planned, structured, clinical case-based discussions as suggested by other researchers.[15],[19],[21]

Students’ perception of teachers

The domain’s mean score was 26.95 (5.07), which is in the range of ‘more positive than negative’. Item number 2 (the teachers are knowledgeable) scored high among all (3.32 [0.6]). This shows the confidence they have in the teachers because of their rich teaching content and method of teaching. Item 9 (the teachers are authoritarian), which scored <2 (1.73 [1.05]), needs attention. This strict behaviour of teachers is commonly reported in other studies also.[12],[15],[27] However, preclinical students felt better about the teachers than the clinical students. The clinical students feel that the teachers are not good at providing feedback and a constructive criticism, rather they ridicule the students. This is important and a correctable factor. Similarly, female students scored more positive than males (p=0.028).

Students’ academic self-perception

The mean domain score was 19.1 (4.63). Even though it was in the more positive range, this domain scored the lowest (59.69%). Both male and female students felt difficulty in learning and memorizing the vast content of this curriculum. Two problem areas recognized in this domain are item number 5 (learning strategies that worked for me before continue to work for me now) and item number 27 (I am able to memorize all I need)—both scored <2. The problem expressed by the students through item 5 indicates that our students came from various educational backgrounds, especially for the students in the initial year of study. The same concern was expressed by Till.[31] The curriculum overload seems to be a problem expressed by medical students almost all over the world.[12],[15],[19],[29],[30] The mean score for basic science students were higher (19.6 [4.48]) than the clinical students (18.65 [4.7]), with a significant p=0.03. Similar results were observed in few other studies as well.[13],[27] This is again in concordance with students’ perception of learning domain, where similar increased difficulty and negative perception were noted by the clinical students. The mostly unstructured teaching schedule on the bedside, teaching methodology and vast curriculum in clinical teaching may be the reasons for this dissatisfaction expressed by the clinical batch students. The score of the preclinical students were better as they are exposed to classroom teaching, which is similar to their school days teaching. As they move on to the clinical side, the sudden change in the learning pattern, application of theory during patient interaction, examination and diagnosis and long sessions of case presentations in the outpatient department and ward might have been more stressful to them, leading to lower scores in the clinical year.

Remedial measures can be taken in the form of microplanning the clinical teaching sessions, prior intimation about the case to be discussed, giving time for them to prepare and early clinical exposure in the 1st year itself.

Students’ perception of atmosphere

This domain scored the highest among all domains (62.5%) with a mean of 30 (6.26). JIPMER atmosphere is better perceived by female students (30.77 [6.10]) than their male counterparts (p=0.02; [Table - 1]). Apart from the stress they feel in studying medicine (2.07), generally they felt that atmosphere during lectures, symposiums and ward teachings was relaxed and it is well scheduled. There is no item in this domain which scored <2. Hence, our atmosphere could be enhanced with little effort from the curriculum planners and teachers. The preclinical batch felt that the institute is well scheduled (p=0.001), similar to other studies.[15],[21] This is mainly due to the inherent challenges of clinical teaching such as time pressure, opportunistic teaching, increasing number of students, limited resources, clinical environment not ‘teaching friendly’ and poor rewards and recognition for teachers.[32]

Students’ social self-perception

It was good to know that the institute has provided a decent accommodation for all the students as this item scored >3. They were also satisfied about their friends (score was 3.25). But, the worrisome feature is the lack of good support system for the students who felt stressed and bored of the system, similar to other studies.[12],[15],[21],[30] This needs immediate attention from the administrators and curriculum planners. We at JIPMER have a mentorship programme to provide necessary psychological and academic support for the mentees throughout their course. Our results suggest that our mentorship programme has to be fine- tuned to the need of the students and we have to look into the finer details such as time spent with the mentee and means to improve the interpersonal relationship with mentor and mentee. There is no statistical difference between the basic science and clinical group in the SSP. For the ninth semester, the score was 15.69, which was the lowest among all semesters, showing the amount of pressure they have to handle in their final clinical year [Table - 4].

Areas of concern and remedial measures planned

Converting the DREEM results into a strategic plan is a difficult task, and a literature search revealed that institutions do not mention their plan of action after the study. A similar concern was expressed by Till.[31] Our areas of concern and proposed remedial measures are:

- Male students’ perception of educational atmosphere is inferior to their female counterparts, especially in perception of learning. We plan to submit a recommendation to the curriculum planning committee to include more laboratory work, demonstration, interactive sessions, role playing, students’ topic discussion and small group discussion.

- Overemphasized factual learning and authoritarian teachers were the students’ concerns. We are planning to increase the PBL sessions, small group learning and students’ active participation. We are planning to take constant feedback from students about teachers and teaching strategies and conduct regular discussion sessions among faculties to improve our approach.

- Students felt there was no good support system for students who get stressed and often they get bored. We are running a mentorship programme for all undergraduate students. As students feel that the support system is not good, we propose to restructure our programme. Mentors are not trained counsellors, so we plan to recommend to the administrators to train mentors in these aspects, and after identifying the stressed candidate by the mentors, they can get special attention from a psychologist for further help.

Conclusion

Our study provided useful information about the educational environment of students in JIPMER. The DREEM inventory generated a ‘profile’ of our institution’s strengths and weaknesses as perceived by our students. These baseline data can be used to monitor the educational environment in future. We have identified few areas of concern such as overemphasis on factual learning, authoritarian teachers, the not so helpful previous learning strategies, vast curriculum (an inability to memorize all), lack of support system for stressed students and the boredom they felt in the course. These vital areas will be addressed by stakeholders in the institute to improve the learning environment and learning experience of the students.

Conflicts of interest. None declared

| 1. | Roff S, McAleer S, Ifere OS, Bhattacharya S. A global diagnostic tool for measuring educational environment: Comparing Nigeria and Nepal. Med Teach 2001;23:378-82. [Google Scholar] |

| 2. | Genn JM. AMEE Medical Education Guide No 23 (Part 1): Curriculum, environment, climate, quality and change in medical education—a unifying perspective. Med Teach 2001;23:337-44. [Google Scholar] |

| 3. | Roff S, McAleer S, Harden RM, Al-Qahtani M, Ahmed AU, Deza H, et al. Development and validation of the Dundee Ready Education Environment Measure (DREEM). Med Teach 1997;19:295-9. [Google Scholar] |

| 4. | Roff S. The Dundee Ready Educational Environment Measure (DREEM)—a generic instrument for measuring students’ perceptions of undergraduate health professions curricula. Med Teach 2005;27:322-5. [Google Scholar] |

| 5. | Jiffry MT, McAleer S, Fernando S, Marasinghe RB. Using the DREEM questionnaire to gather baseline information on an evolving medical school in Sri Lanka. Med Teach 2005;27:348-52. [Google Scholar] |

| 6. | Aghamolaei T, Fazel I. Medical students’ perceptions of the educational environment at an Iranian Medical Sciences University. BMC Med Educ 2010; 10:87. [Google Scholar] |

| 7. | Arzuman H, Yusoff MS, Chit SP. Big Sib students’ perceptions of the educational environment at the school of medical sciences, Universiti Sains Malaysia, using Dundee Ready Educational Environment Measure (DREEM) Inventory. Malays J Med Sci 2010;17:40-7. [Google Scholar] |

| 8. | Riquelme A, Oporto M, Oporto J, Méndez JI, Viviani P, Salech F, et al. Measuring students’ perceptions of the educational climate of the new curriculum at the Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile: Performance of the Spanish translation of the Dundee Ready Education Environment Measure (DREEM). Educ Health (Abingdon) 2009;22:112. [Google Scholar] |

| 9. | Rotthoff T, Ostapczuk MS, De Bruin J, Decking U, Schneider M, Ritz-Timme S. Assessing the learning environment of a faculty: Psychometric validation of the German version of the Dundee Ready Education Environment Measure with students and teachers. Med Teach 2011;33:e624-36. [Google Scholar] |

| 10. | Shankar PR, Dubey AK, Balasubramanium R. Students’ perception of the learning environment at Xavier University School of Medicine, Aruba. J Educ Eval Health Prof 2013;10:8. [Google Scholar] |

| 11. | Xu X, Wu D, Zhao X, Chen J, Xia J, Li M, et al. Relation of perceptions of educational environment with mindfulness among Chinese medical students: A longitudinal study. Med Educ Online 2016;21:30664. [Google Scholar] |

| 12. | Abraham R, Ramnarayan K, Vinod P, Torke S. Students’ perceptions of learning environment in an Indian medical school. BMC Med Educ 2008;8:20. [Google Scholar] |

| 13. | Kim H, Jeong H, Jeon P, Kim S, Park YB, Kang Y. Perception study of traditional Korean medical students on the medical education using the Dundee ready educational environment measure. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2016;2016:6042967. [Google Scholar] |

| 14. | Abraham R, Ramnarayan K, Pallath V, Torke S, Madhavan M, Roff Sue. Perceptions of academic achievers and under-achievers regarding learning environment of Melaka Manipal Medical College (Manipal campus), Manipal, India, using the DREEM Inventory. South-East Asian J of Med Educ. 2007;1:18-24. [Google Scholar] |

| 15. | Kohli V, Dhaliwal U. Medical students’ perception of the educational environment in a medical college in India: A cross-sectional study using the Dundee Ready Education Environment questionnaire. J Educ Eval Health Prof 2013;10:5. [Google Scholar] |

| 16. | Mayya S, Roff S. Students’ perceptions of educational environment: A comparison of academic achievers and under-achievers at Kasturba medical college, India. Educ Health (Abingdon) 2004;17:280-91. [Google Scholar] |

| 17. | Al-Hazimi A, Al-Hyiani A, Roff S. Perceptions of the educational environment of the medical school in King Abdul Aziz University, Saudi Arabia. Med Teach 2004;26: 570-3. [Google Scholar] |

| 18. | Cocksedge ST, Taylor DC. The National Student Survey: Is it just a bad DREEM? Med Teach 2013;35:e1638-3. [Google Scholar] |

| 19. | Edgren G, Haffling AC, Jakobsson U, McAleer S, Danielsen N. Comparing the educational environment (as measured by DREEM) at two different stages of curriculum reform. Med Teach 2010;32:e233-8. [Google Scholar] |

| 20. | Patil AA, Chaudhari VL. Students’ perception of the educational environment in medical college: A study based on DREEM questionnaire. Korean J Med Educ 2016;28:281-8. [Google Scholar] |

| 21. | Demirören M, Palaoglu O, Kemahli S, Ozyurda F, Ayhan IH. Perceptions of students in different phases of medical education of educational environment: Ankara university faculty of medicine. Med Educ Online 2008;13:8. [Google Scholar] |

| 22. | Bakhshi H, Bakhshialiabad MH, Hassanshahi G. Students’ perceptions of the educational environment in an Iranian Medical School, as measured by The Dundee Ready Education Environment Measure. Bangladesh Med Res Counc Bull 2014;40:36-41. [Google Scholar] |

| 23. | Rahman NI, Aziz AA, Zulkifli Z, Haj MA, Mohd Nasir FH, Pergalathan S, et al. Perceptions of students in different phases of medical education of the educational environment: Universiti Sultan Zainal Abidin. Adv Med Educ Pract 2015;6:211-22. [Google Scholar] |

| 24. | Wehrwein EA, Lujan HL, DiCarlo SE. Gender differences in learning style preferences among undergraduate physiology students. Adv Physiol Educ 2007;31:153-7. [Google Scholar] |

| 25. | Fleming ND. Teaching and learning styles: VARK strategies. Christchurch:IGI Global; 2001. [Google Scholar] |

| 26. | Kharb P, Samanta PP, Jindal M, Singh V. The learning styles and the preferred teaching-learning strategies of first year medical students. J Clin Diagn Res 2013;7:1089-92. [Google Scholar] |

| 27. | Pai PG, Menezes V, Srikanth, Subramanian AM, Shenoy JP. Medical students’ perception of their educational environment. J Clin Diagn Res 2014;8 (1): 103-7. [Google Scholar] |

| 28. | Mohd Said N, Rogayah J, Hafizah A. A study of learning environments in the kulliyyah (faculty) of nursing, International Islamic University Malaysia. Malays J Med Sci 2009;16:15-24. [Google Scholar] |

| 29. | Veerapen K, McAleer S. Students’ perception of the learning environment in a distributed medical programme. Med Educ Online 2010;15:5168. [Google Scholar] |

| 30. | Thomas BS, Abraham RR, Alexander M, Ramnarayan K. Students’ perceptions regarding educational environment in an Indian dental school. Med Teach 2009;31:e185-6. [Google Scholar] |

| 31. | Till H. Identifying the perceived weaknesses of a new curriculum by means of the Dundee Ready Education Environment Measure (DREEM) Inventory. Med Teach 2004;26:39-45. [Google Scholar] |

| 32. | Spencer J. Learning and teaching in the clinical environment. BMJ 2003;326: 591-4. [Google Scholar] |

Fulltext Views

3,667

PDF downloads

1,806