Translate this page into:

Public hospitals in Madras and people associated with them

Correspondence to ANANTANARAYANAN RAMAN; anant@raman.id.au; Anantanarayanan.Raman@CSIRO.au; araman@csu.edu.au

To cite: Raman R, Raman A. Public hospitals in Madras and people associated with them. Natl Med J India 2022;35:112–17.

Abstract

In this follow-up article, we refer to the other public hospital facilities of Madras, viz. the Lock and Naval Hospitals, the Native Infirmary, Lunatic Asylum, Eye Infirmary, Maternity Hospital (Egmore), and the Queen Victoria Hospital for Caste and Gosha Women, some of which are operational today. We also include brief notes on a few of the pioneering men and women, who contributed to the development of these facilities.

INTRODUCTION

This is a follow-up article of the one on the Madras General Hospital.1 Here, we chronicle the events and developments in the other major public health facilities in Madras town, of which the early lock and naval hospitals are extinct. Because people and edifices cannot be separated in historical chronicles, we have also referred to a few key people, who contributed by setting milestones in this context.

THE LOCK HOSPITAL

The mid-19th century army health statistics of Madras and India indicate that morbidity rates were especially high (nearly 30%) among soldiers suffering from sexually transmitted diseases (STDs).2 One Assistant Surgeon—John Clark––indicates that more cases of STD occurred in one army regiment in India than in the whole of the Caribbean island nations.3 The Madras Army surgeons contended that syphilis and gonorrhoea were modestly different manifestations of the same disease. Their faith was founded on the belief that two men may have had contact with the same woman, and one could contract syphilis and the other gonorrhoea.3

The government in Bengal made an effort to combat STD by establishing ‘lock’ hospitals in 1807. Lock hospitals were dedicated clinics for those suffering from venereal diseases. The earliest one was the London Lock Hospital, established in 1747. Traditionally the term ‘lock’ referred to the ‘rags’ used by patients of leprosy to cover themselves. Therefore, the lock hospitals implied hospitals treating patients of leprosy. However, these hospitals came to be better known for patients suffering from venereal diseases in later times.4

Following Bengal, the Madras Army established lock hospitals in major army stations in the Madras Presidency. By 1810, about 3500 women were coercively and punitively treated in lock hospitals in Madras presidency. Even a ‘medical police’ was contemplated to monitor prostitution and its public-health consequences, although this did not eventuate. Funding for these hospitals was calculated by a combination of an allocated amount for facilities and a per-capita fee levied on every treated person. William Bentinck (1774–1839), Governor of Madras (1803–07) and the Governor-General in Calcutta (1828–34) was, however, not happy with the coerciveness enforced in this context. To Bentinck, the lock hospitals were a short-term solution; they did nothing for the involved female, but only checked the spread of infection among the troops, that too, indirectly. Consequently, the lock hospitals were shut down in Madras Presidency. However, the story does not end there. There was a substantial increase in the rate of incidence of venereal diseases by 1835, implicated as due to the abolition of lock hospitals.5 Caught between what were unacceptable levels of venereal infection and London’s disapproval of continuation of lock hospitals, some Madras Army officers, colluding with a few local surgeons, planned makeshift arrangements. Voluntary lock hospitals and dispensaries re-emerged, where free treatment, shelter and food were offered to ‘attract’ destitute women. The lock hospitals reappeared formally in the 1850s with the establishment of one by the Madras Government in Cannanôre (Kannûr, a part of the Madras Presidency until 1956; presently a district of the State of Kerala) in 1849.6 Lock hospitals functioned in the Madras Presidency until the 1890s. About this time, the Government in Madras planned to employ women nurses at these facilities as an improvement measure, which was rejected by the Government of India.7 Surgeon General George Smith in his consolidated report8 on the lock hospitals in India, published in 1878, indicates that one lock hospital existed in Madras town in 1877. This report8 describes the conditions and staffing in and expenditure of lock hospitals in Madras presidency. This report8 also supplies comprehensive statistics of various venereal diseases, especially those of syphilis and gonorrhoea in the decade from 1867 to 1877.

THE NAVAL HOSPITAL

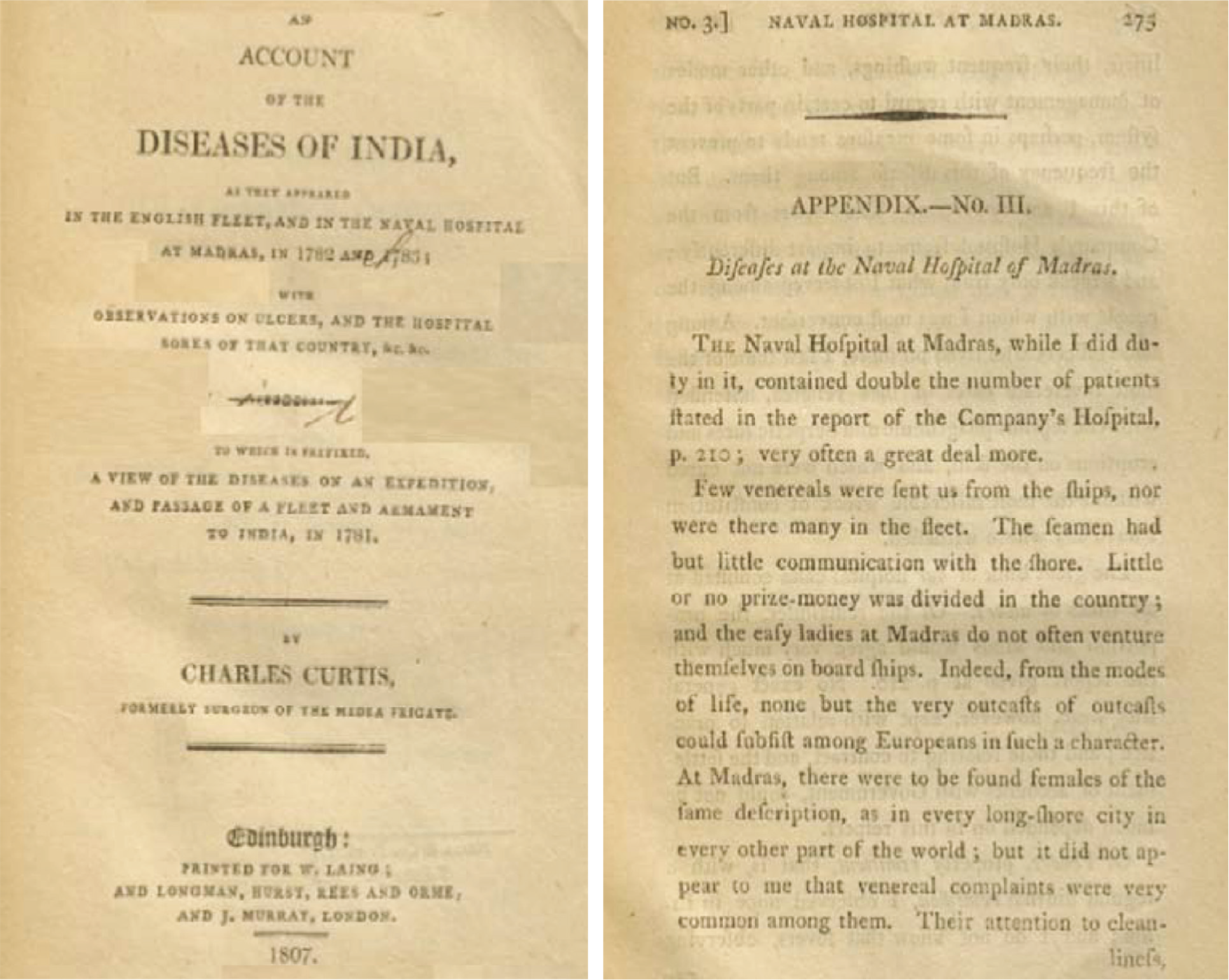

An exclusive hospital was built in Madras (commencement 1784; completion 1808) for sick seamen travelling on British frigates to countries governed by Britain9 (Fig. 1). Until 1808, the Military Hospital (MH) operating within the Fort St George1 serviced the sick seamen as well. The MH included two independently managed wings: a ‘garrison hospital’ on the western side of the building and a ‘naval hospital’ on the eastern side. After establishment, from 1808, the Madras Naval Hospital (MNH) treated European and Eurasian (Anglo-Indian) civilians. For a glimpse of the structure of the MNH and the common diseases that were treated therein, see Charles Curtis,10 who also provides the medical history in Madras until 1808 (Fig. 2). The MNH, located in an exclusive building at the dedicated site, was closed in 1831 and the building was converted to a gun-carriage factory. The road that housed the Naval Hospital was known as the ‘Naval Hospital Road’, presently renamed as ‘Jothi Venkatachellum Road’. This road is opposite to the Government College of Fine Arts on Poonamalee High Road. The premises are presently used as the medical-store depot of the Government of Tamil Nadu.

![The Madras Naval Hospital (c. 1815) (Aquatint by J. Inman, Esqr. (del.—delineavit, ‘drawn by’ [inscription along the left bottom of the aquatint] and engraved (‘Sculp.—sculpsit ’) by J. Baily (inscription along the right bottom of the aquatint). Artist Inman’s identity is not determinable: possibly he was a sailor who had the artistic skill, who came to the Naval Hospital for some reason. Very likely engraver Baily engraved Inman’s aquatint in Britain, since Baily had never travelled to India (source: http://wellcomeimages.org/indexplus/obfimage/jpg)](/content/141/2022/35/2/img/NMJI-35-112-g001.png)

- The Madras Naval Hospital (c. 1815) (Aquatint by J. Inman, Esqr. (del.—delineavit, ‘drawn by’ [inscription along the left bottom of the aquatint] and engraved (‘Sculp.—sculpsit ’) by J. Baily (inscription along the right bottom of the aquatint). Artist Inman’s identity is not determinable: possibly he was a sailor who had the artistic skill, who came to the Naval Hospital for some reason. Very likely engraver Baily engraved Inman’s aquatint in Britain, since Baily had never travelled to India (source: http://wellcomeimages.org/indexplus/obfimage/jpg)

- (Left) Cover page of Charles Clark’s volume (1807); (right) Clark’s description of the Diseases at the Naval Hospital of Madras (pp. 273–5)

THE MADRAS NATIVE INFIRMARY

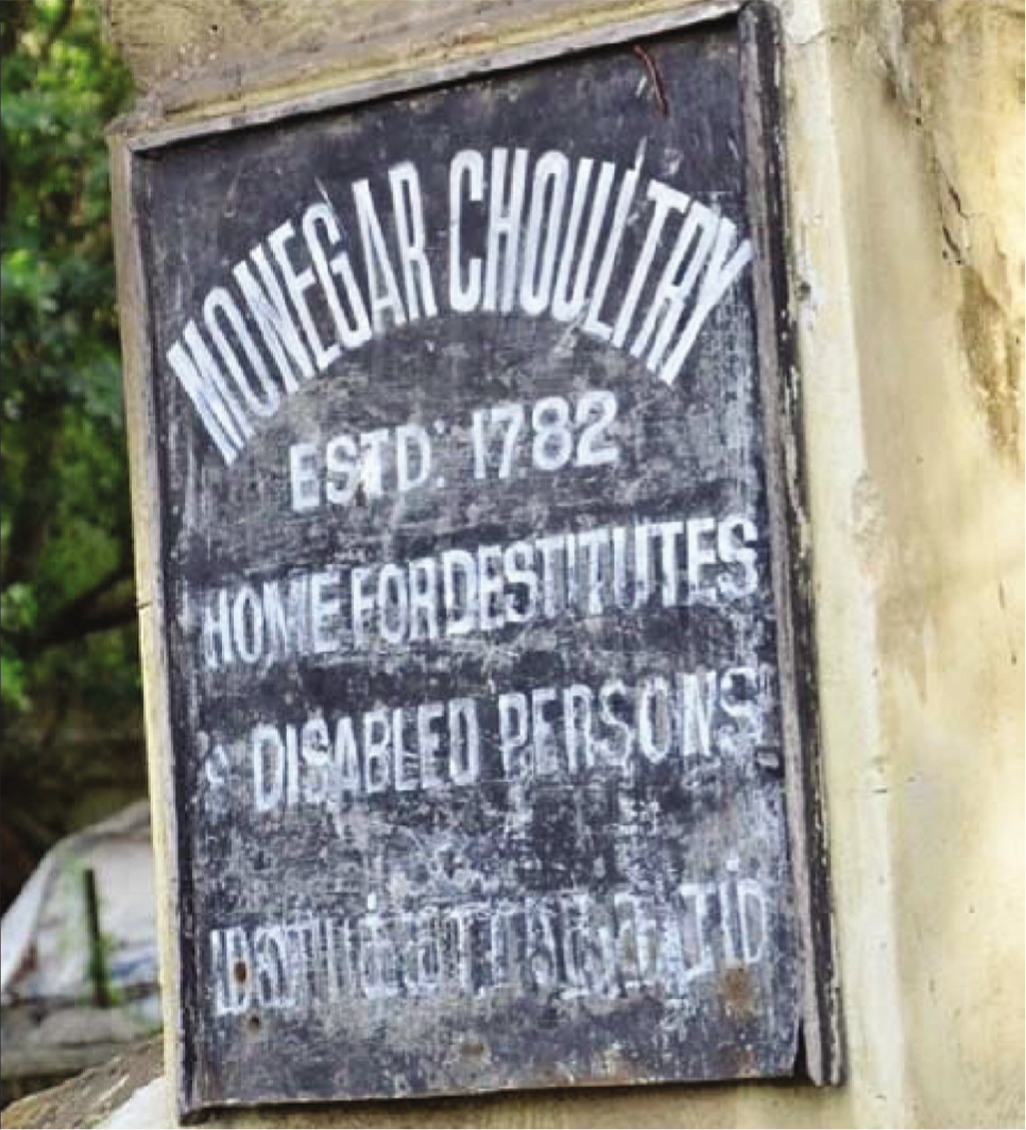

The Madras Native Infirmary (MNI) was established for the sole purpose of providing medical help to the native poor of Madras in 1799. The MNI was attached to the Monégar Choultry (MC), which was the English corruption of Maniyakkãrar Çattiram (Tamil).11 A Çattiram (anglicized as Choultry) was a free, short-term rest facility for passers-by and travellers. MC was operational from 1784 as a centre to disburse kanjí (sour-rice porridge, gruel) free to the famine-stricken poor of Madras. Assistant Surgeon John Underwood suggested setting up an hospital at MC in 1797, which evolved as the MNI in 1799. The government made available `54 358 to the newly established MNI, treating it as a joint charity as unredeemable government securities in 1809.12 The MNI (Fig. 2) grew into a ‘hospital’ shortly after, with the construction of a few pent-roofed brick sheds. This facility included exclusive male and female wards, separated by a high wall to accommodate 140–150 lying-in patients at a time. The wards were well aerated with doors and windows further to ventilators in the roof. An ‘excellent’ surgery was done within, in addition to the quarters for an apothecary, and a dispensary to issue medications to outpatients.13 John Underwood was the first superintendent. This hospital was managed by a team consisting of Merchant William Webb and Aldermen Nathaniel Kindersley, Charles Baker and John de Fries. In the first decade of the 19th century this hospital was managed by the MC administration.

- Surviving plaque referring to the Monégar Choultry, North Madras (source: https://www.facebook.com/779175858839390/posts/2019)

This facility included seven separate ‘cells’ for the mentally ill, both men and women. The most critical inclusion at the MNI precinct was the Leper Hospital, which was in a building separated by a 12 feet (c. 4 m) high wall. This facility could accommodate 110 patients (50 Indo-Britons [Anglo-Indians] and 60 Indians). The Leper Hospital and other facilities within the MNI precincts were divided by a road that passed by (today, the Ennore High Road) to avoid interactions among inmates of the two hospitals.14,15

A statistical report dated 1842 indicates that between 1827 and 1838, 12 446 patients were treated at the MNI and the mortality rate was 25%. Remittent and eruptive fevers, cholera, diarrhoea, atrophia, phlogosis and ulcers were few of the major illnesses treated.16 The MNI grew first into the Royapuram Medical School in 1933, and as the Stanley Medical College and Hospital in 1938, named so after George Frederick Stanley, Governor of Madras during 1929–34. The new ‘Licenced Medical Practitioner’ (LMP) diploma offered at the Stanley Medical College and Hospital was an innovation in Madras’s health-management effort, especially after World War I. The government under the premiership of Panangati Ramanarayaningar (a.k.a. the Rajah of Panagal) utilized the LMP qualified personnel in the Subsidized Rural Medical Relief Scheme (SRMRS), a novel health project launched in 1924, which operated with the objectives of bringing medical relief to rural people and encouraging the trained medical practitioners to settle in remote and rural areas.

THE LUNATIC ASYLUM

Support for founding the Madras Lunatic Asylum (MLA) (the Government Mental Hospital until 1978; Institute of Mental Health, presently) in Kilpauk was signed by the Government of Madras in January 1867. A new building for the MLA was constructed in a 66.5-acre Locock’s Garden, Kilpauk, a little outside the municipal limits of Madras town at that time. In May 1871, the MLA commenced functioning with about 150 patients and Surgeon John Murray was its first superintendent.17 The MLA admitted more patients with time: 330 in 1880, 600 by 1900s, and 800 by 1915. Between 1860 and 1915, civilians constituted 80% of the total number of patients admitted into MLA and the remaining were ‘criminal lunatics’.

From the later decades of the 18th century, mentally-ill Europeans and Eurasians in India were minded in private facilities called the ‘madhouses’, the first established in Calcutta in 1787 and in Madras in 1794. Until government’s support started in 1871, the Madras Madhouse was filthy. In 1794–1871, class-specific categories, even among the Europeans, were critical for admission into Madras Madhouse. For instance, one J. Campbell, a criminal lunatic, was not admitted into Madras Madhouse in 1851, because it was unsuitable for his ‘status’; he was housed in a large portion of the local prison.

The Madras Madhouse started in a rented building (@ `825/ month) Purasawalkam (13o08’59"N; 80o25’05"E) in 1794 and was supervised by Valentine Connolly. Surgeon Maurice Fitzgerald held charge until 1803. The exact location of the Madras Madhouse is not traceable today. James Dalton rebuilt it in the location, which can be determined today as the junction between Miller’s Road and in Purasawalkam High Road. Until recently this site with a long two-storey building served as the hostel for men students pursuing law degree at the Madras Law College— the Dr B.R. Ambedkar Government Law College. Until the 1930s, this site, known as College Park, was used as the residence of the Principal of Madras Christian College, before it moved to its spacious Tambaram campus in 1937. Between 1937 and the 1950s, this building served as the hostel for students of the Madras Medical College. Hence, this facility came to be popularly known as Dalton’s Mad Hospital (1807–1815). Psychiatric case notes indicate that Madras surgeons treating the mentally ill used the term ‘circular insanity’, whereas their Bombay contemporaries used ‘impulsive and obsessive insanity’. Circular insanity earlier known as ‘manic depressive illness’ is presently referred as the ‘bipolar illness’. By 1915, nearly 45% of the examined cases were classified as ‘mania’ and 18% as ‘melancholia’ in Madras. A quarter of the total number of patients admitted in 1914 were suffering from dementia. Besides using the moral-management tactics, by early 20th century treatment using oral medications was gaining popularity aiming at controlled patient behaviour and inducing sleep. For example, administration of chloral hydrate (hydrated trichloroacetaldehyde) was used to treat insomnia. Morphine was used to restrict hyperexcitation and induce rest. The Superintendent of MLA (1873–74) found using a little wine or arrack at bedtime useful in inducing sleep in the patients; and the use of opiates was not preferred.18

THE EYE INFIRMARY

A modest facility with the name the Madras Eye Infirmary (MEI) was established in 1819. MEI is the oldest exclusive eye hospital in Asia and the second oldest dedicated ophthalmic facility in the whole world, after Moorfields Eye Hospital in London (established in 1805). With an increased recognition of eye and related problems faced by the soldiers of the Madras Army in the early decades of the 19th century, the Madras government sought advice from Benjamin Travers (1783–1858), earlier with the Moorfields and later with the St Thomas’s Hospitals in London. Travers recommended one Robert Richardson for appointment in Madras as an ophthalmic surgeon; his suggestion was accepted, and Richardson was appointed as an ophthalmic surgeon in Madras. The MEI, under his direction, was first established in a residential house in Royapettah (13°03'14" N; 80°15'51" E) in July 1819 and was subsequently shifted to Marshall’s Road, Egmore (13°07'8" N; 80°25'9" E), where it is located presently.

In the early decades of the 19th century, the MEI, as a health facility, was the second largest hospital in Madras, next in size only to the Madras General Hospital. The MEI was renamed as the Madras Ophthalmic Hospital (MOH) in the 1900s when Drake Brockman was the superintendent. At this time, this hospital was a heartburn to medical personnel in other Indian presidencies in the late 19th century. Lieutenant Colonel F(rederic) P(insent) Maynard of the Bengal Medical Service, while speaking on the need for a new ophthalmic hospital in Calcutta19,p. 208 had the following to say:

The principal interest of that communication lay in the fact that the new eye hospital for Calcutta was still only in the state of being ‘proposed’. Years ago, when the Madras Eye Hospital was still incomplete, but yet had made considerable progress towards its present condition.

By 1909, the MOH included 80 beds and about 150 patients were treated as outpatients. Separate wards—the Connemara for the military personnel and the Wenlock for women—were added. Superintendents Robert Elliott (1904–1913), Henry Kirkpatrick (1914–1920) and Robert Wright (1920–1938) are prominent names inscribed in the annals of the GOH. Elliott pioneered in performing sclerocorneal trephining to treat chronic glaucoma, which is known today as Elliott’s ‘trephination procedure for open-angle glaucoma’.20 Kirkpatrick established the Elliott School of Ophthalmology. Wright started the academic programme ‘Licentiate in Ophthalmology’ (LO), first of its kind in India. K. Kôman Nayar, the first Indian superintendent, upgraded the LO programme to ‘Diploma in Ophthalmology’ in 1942. R.E.S. Muthayya became the superintendent of GOH in 1947; he not only contributed to the growth of the hospital, but also introduced several academic novelties. With government’s support in independent India, Muthayya pioneered by setting up the ‘first’ eye bank in the whole of India in 1945. Muthayya performed the first corneal transplant surgery in India in 1948. During Muthayya’s superintendence, MS (Ophthalmology) programme commenced in the MOH. (For a detailed note of the MOH, see Raman and Raman.21)

THE MATERNITY HOSPITAL

The maternity hospital in Egmore in 1844 marks the start of professional obstetrics rendered at a hospital scale in India.22 Arcot Lakshmanaswami Mudaliar, a popular gynaecologist– obstetrician of Madras said at the inaugural session of the First All-India Obstetrics and Gynaecological Congress in Madras in 1936:23

…But Madras is proud, and justly so, of the place it occupies in the Obstetric world of today and it is in no spirit of narrow provincialism that I venture to maintain that no other city in Indian could have claimed this honour with greater confidence and dignity.…

The first formal, western science-based lying-in hospital for expecting mothers was this one, first named the ‘Government Maternity Hospital’. When started, this hospital—raised out of public donation—was close to the Egmore railway station (13°07'8" N; 80°26'16" E). However, the government paid for the staff and supplied food to patients. A committee of six medical officers, who offered their services gratis, supervised. James Shaw, the first professor of Midwifery, Madras Medical College, 1847, held charge as the superintendent of this hospital. This facility moved to the present location on Pantheon Road, just 0.6 mile (~1 km) away from the previous location in Egmore in 1870 and was formally commissioned in 1881. By 1890s, the Pantheon Road hospital expanded to include 150 beds. By 1900s, five new buildings were added so as to accommodate beds for 140 lying-in patients. William Thompson was the superintendent during 1848–1851. Gerald Giffard (Superintendent, 1905–1917) constructed a separate teaching block. A few random Internet reports (e.g. www.missosology.info/forum/viewtopic.php?t=22025, accessed on 30 September 2021) indicate Arthur Branfoot (Superintendent) successfully delivered the baby of Supayalat, the queen of Burma, in 1886, who was exiled to Madras along with the Burmese king and her husband Thibaw-Min of the Konbaung dynasty (r. 1878–1885).

A children’s ward was added to this hospital in 1949 with 28 beds, thanks to the efforts of Šãntanûri Thirûmalãchãr (S.T. Ãchãr) [Portrait 1]. S.T. Ãchãr is remembered for his Textbook of paediatrics, which is running its fourth, revised edition presently as Achar’s textbook of pediatrics edited by Swarna Rekha Bhat, St John’s College and Hospital, Bengaluru, published by Orient BlackSwan, Hyderabad (2009). The combined facility was renamed as the ‘Egmore Women and Children Hospital’ (EWCH) in later years, and presently is the ‘Institute of Child Health and Hospital for Children’ (ICH–HC).

- S.T. Ãchãr

The credit for establishing a children’s ward in the Madras maternity hospital solely goes to Ãchãr that a single children’s ward has grown today into the ‘Institute of Child Health and Hospital for Children’ as an offshoot of the Egmore Women’s Hospital.

The concept of combining management of health of women and children was so unique in the 1940s that this combined women and children hospital came to be referred as the ‘Egmore Model’ in medical circles.24 This facility became a teaching centre with postgraduate and diploma programmes in Obstetrics and Gynaecology in 1930, while remaining as a department of the Madras Medical College, teaching various aspects of women-and-children-health management.

THE QUEEN VICTORIA HOSPITAL FOR WOMEN

Mary Anne Scharlieb, in 1883, returning to Madras after qualifying MD from the London Medical School for Women and with a Diploma in Midwifery from Vienna, was keen to establish a dedicated women’s hospital in Madras. With support from the Madras government and that of Edward Balfour, the Surgeon-General,25 Scharlieb established a second women’s hospital in Moore’s Garden, Nungambakkam. Moore’s Garden is named after George Moore of Madras Civil Service, a Civil Auditor until 1814. Currently Moore’s Road exists but not the garden. In 1884, with some support from the Countess-of-Dufferin Fund, this hospital later grew into the Queen Victoria Hospital for Caste and Gosha Women (presently, Institute of Social Obstetrics and Kasturba Gandhi Hospital for Women and Children). Scharlieb, a person of distinction in Madras’s Medical history, returned to England in 1887.26

What was established as a small hospital required to be rebuilt as a larger facility. Anna-Julia Webster (the spouse of Mountstuart Elphinstone Grant Duff, Governor of Madras, 1881–1886) along with Kasturi Bashyam Iyengar, R. Raghunatha Rao, Pusapati Vijayram Gajapati Raju (Raja of Vizianagaram), S. Muthuswamy Iyer, the Raja of Venkatgiri, and Raja Sir Savalai Ramaswamy Mudaliar, premier citizens of Madras played key roles in re-developing this hospital. The government donated a site in Triplicane (Chepauk, 13°06'2" N; 80°28'04" E) in 1890 and supplemented the effort with `10 000. The main building was constructed through the munificence of the Raja of Venkatagiri, who donated `100 000. The hospital founded in Egmore moved to its present location Triplicane in June 1890. The government under the leadership of Agaram Subbarãyalû Reddiãr took over the management of this hospital in April 1921. That this hospital established a name for itself through the sustained efforts of pioneering women doctors of Madras: Mary Beadon, Hilda Mary Lazarus and E. Madhuram is well known.27

What is not clear is why Scharlieb preferred to open a second hospital, when the Egmore Maternity Hospital was already in operation. Scharlieb was strongly influenced by Frances Hoggan, who affirmed in Indian women’s preference of women doctors and who emphasized the need for enrolling women in medical schools in Britain.28 The British parliament discussed this issue and the 1876 law enabled women doctors to qualify and practise. The UK Medical Act of 1876 (Ch. 41: 39, 40) repealed the previous Medical Act allowing the medical authorities to license all qualified applicants irrespective of gender. In 1877, the Royal Free Hospital allowed students at the London Medical School for Women (LMSW) to complete their clinical studies there. The Royal Free Hospital was the first teaching hospital in London to admit women for training.

Non-preference of male doctors by Hindu and Muslim women during childbirth was one vigorous social reason in 19th century India. The commitment to provide female doctors to the ‘conservative’ women of Madras could have been the principal driver in Scharlieb setting up a second women’s and a women-doctor clinic in Egmore, which grew into the Queen Victoria Hospital in Chepauk later in the Muslim-population dominated Triplicane. A similar explanation features in the life of Ida Sophia Scudder (1870–1960),27 who dreamt of setting up a health facility in southern India. According to the Australian Friends of Vellore:29

One eventful night in 1890, Ida, then a young girl visiting her missionary parents in South India was asked to help three women from different families struggling in difficult childbirth. Custom prevented them from accepting the help of a male doctor and being without training at the time Ida herself could do nothing.

CONCLUSION

The general, maternity, ophthalmic, leper, the lock hospitals were administered by the government, whereas the Corporation of Madras supported the Royapettah and Triplicane Dispensaries. The Triplicane Dispensary possibly functioned in Triplicane High Road. One prominent name associated with this dispensary was Mohideen Sheriff (spelt as ‘Mooden Sheriff’ in many Government-of-Madras documents), who was an early graduate of the Madras Medical College, earning the title GMMC (Graduate of Madras Medical College). Mohideen Sheriff made considerable contributions to the Pharmacopoeia of India in 1869.30 Presently, the Chennai Corporation manages the Infectious Diseases Hospital (Communicable Diseases Hospital, today) in Tôndiãrpét. The Royapettah Dispensary was started as a lying-in facility with a few beds in the later decades of the 19th century, which was taken over by the government and renamed the Royapettah Hospital. Charles Donovan was the superintendent of this hospital from 1905 to 1919, until his retirement. Private subscriptions and occasional government grants supported the Queen Victoria Hospital and the MNI. The nature of support offered by the Government of Madras reflected vested interests: those hospitals which treated westerners were supported by the state, whereas those serving the locals were to find their monies.

The generosity of a well-remembered philanthropist of Madras, Raja Savalai Ramaswamy Mudaliar (later, Raja Sir Savalai Ramaswamy Mudaliar, Portrait 2) established a reasonably large lying-in hospital in North Madras in 1880. Today, known as the Raja Sir Ramaswamy Mudaliar Lying-in Hospital (popularly RSRM Lying-in Hospital), it was handed over to the Government of Tamil Nadu as a public facility soon after Independence and it has progressed to being a popular maternity hospital serving North Madras residents, most of them from the lower- and middle-income groups.

- Savalai Ramaswamy Mudaliar

The Tuberculosis Sanatorium in Tambaram was established by a British-qualified Madras surgeon David Aaron ChowryMuthu in 1928. Although qualified in general medicine (Portrait 3), Chowry-Muthu was passionate in treating pulmonary tuberculosis.31 On return to India, with his British wife Margaret, he established the Tambaram facility––rather a large clinic enabled with lying-in facility––on the principles of sanatorium, which was gaining in prominence in developed nations then. In 1938, he returned to England handing over this facility to the Madras Government. Today this facility has grown as Government Hospital for Thoracic Medicine (GHTM) and provides support to about 750 patients requiring treatment. As a point of interest, the GHTM started admitting patients suffering from HIV from 1993, a bold step taken by this facility.

- David Jacob Aaron and Margaret Chowry-Muthu née Carkeet-Fox (source: https://au.pinterest.com/pin/205124958003503358/)

Today Madras (rather, Chennai) and other district headquarters in Tamil Nadu include large private hospitals aiming at better health management. Whereas these serve the people in terms of offering remediation and treatment, the cost of health management has become prohibitive, especially to those belonging to the lower social strata mainly because of corporatization of health management. In that sense the public hospitals of Madras of yesteryears were remarkable in not only helping people, but also by enabling access to them, mostly free.

References

- On the quarter-millennial anniversary of the Madras General Hospital. Natl Med J India. 2022;35:47-51.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evolution of venereology in India. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2006;72:187-97.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burdens of history. British feminists, Indian women, and Imperial culture 1865-1915. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press;

- [Google Scholar]

- Reports of the Deputy Inspector of hospitals to the Director General of the army medical department. Madras Quart Med J. 1839;1:435-44.

- [Google Scholar]

- Soldiers, surgeons and the campaigns to combat sexually transmitted diseases in Colonial India 1805-1860. Med Hist. 1998;42:137-60.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Revising approaches to diseases and medicine in the long nineteenth century. The Historian. 2007;5:57-72.

- [Google Scholar]

- Annual report of the lock hospitals of the Madras Presidency for the year 1877. Madras:Government Press; 1878:31.

- [Google Scholar]

- The Royal Naval Medical Service from the earliest times to 1918. British Naval History. Available at www.britishnavalhistory.com/wickstead_rnms_earliest_times/2013 (accessed on 6 Jun 2021)

- [Google Scholar]

- An account of the diseases of India, as they appeared in the English fleet, and in the Naval Hospital at Madras, in 1782 and 1783; with observations on ulcers, and the hospital sores of that country, &c &c Edinburgh: W. Laing; London:Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, & J. Murray; 1807:283.

- [Google Scholar]

- Miscellaneous; Asiatic Intelligence-Madras. Asiat J Mon Reg Brit Ind Depend. 1825;XIX:88-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Report on the medical topography and statistics of the presidency division of the Madras Army: including Fort St.George and its dependencies, within the limits of the Supreme Court (compiled from the records of the Medical Board Office) London: Royal College of Physicians; 1842. p. :111.

- [Google Scholar]

- Vestiges of old Madras 1640-1800 traced from the East India Company's records preserved at Fort St. In: George and the India Office and from other sources. Calcutta: London: Government of India; Calcutta: London: John Murray; 1913. p. :593.

- [Google Scholar]

- A brief historical sketch of the Madras Leper Hospital, with some notices of leprosy as seen at that institution. Madras Q J Med Sci. 1861;3:271-94.

- [Google Scholar]

- The Madras Leper Hospital and leprosy management in 19th century India. Curr Sci. 2012;103:1354-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- The Madras yearbook with an official, commercial and general directory of the Madras Presidency. Madras: Government Press; 1923. p. :1180.

- [Google Scholar]

- Private psychiatric care in the past: with special reference to Chennai. Indian J Psychiatr. 2008;50:67-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Annual report of the lunatic asylums in the Madras presidency, 1877-1878 Report No. 339. Madras: Superintendent of the Government Press; 1878. p. :12.

- [Google Scholar]

- Glaucoma, a handbook for the general practitioners. London: H.K. Lewis & Company; 1917. p. :60.

- [Google Scholar]

- On the 200th anniversary of the Madras Eye Infirmary, the first ophthalmic hospital in Asia. Curr Sci. 2020;118:1313-21.

- [Google Scholar]

- Birth on the threshold: Childbirth and modernity in South India. Berkeley:University of California Press; 2003:310.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silver jubilee of the federation of obstetric and gynaecological societies of India 1950-1975. J Obstet Gynaecol India. 1976;26:183-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Women doctors and women's hospitals in Madras with notes on the related influencing developments in India in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Curr Sci. 2019;117:1232-40.

- [Google Scholar]

- Dr Ida Scudder. Available at http://australianfov.net.au/about-friends-of-vellore-australia/dr-ida-s-scudder/ (accessed on 23 Jun, 2021)

- [Google Scholar]

- Medical stores in 1865, pharmacist training and pharmacopoeias in India until the launch of the Indian Pharmacopoeia in 1955. Curr Sci. 2018;114:1358-66.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Pulmonary tuberculosis: its etiology and treatment. a record of twenty-two years' observation and work in open-air sanatoria. London: Ballière, Tindall & Cox; 1922. p. :381.

- [Google Scholar]