Translate this page into:

Sensitizing nursing faculty about formation of professional identity: Exploration of lessons learnt at a nursing institute in India

Corresponding to JAGDISH VARMA; jagdishrv@charutarhealth.org

[To cite: Pandya H, Dongre A, Ghosh S, Prabhakaran A, Prakash RH, Panchal S, et al. Sensitizing nursing faculty about formation of professional identity: Exploration of lessons learnt at a nursing institute in India. Natl Med J India 2024;37:145–8. DOI: 10.25259/NMJI_705_2023]

Abstract

Background

We initiated a conversation regarding the concept of professional identity formation (PIF) with faculty of Institute of Nursing at our university through a participatory workshop. We report the planning and conduct of the workshop, as well as lessons learnt from the discussions in the workshop.

Methods

We designed and implemented a day-long workshop for 28 nursing faculty at Institute of Nursing, Bhaikaka University, Gujarat. The expected learning outcomes of the workshop were to: (i) understand the concept of PIF and process of socialization; (ii) identify factors influencing socialization; and (iii) discuss strategies to support PIF. The workshop included a series of four small group discussions, each followed by debriefing. We collected feedback using a questionnaire with 4 open-ended questions and written reflections on the learnings, within 2 days of the workshop. We carried out manual content analysis of text data generated during group work, reflections and feedback.

Results

Twenty-six of the 28 participants responded to the questionnaire. Thirteen mentioned interactions during group activities and discussions with facilitators as a good part of the workshop. Constructive suggestions on improving the workshop were received from 13 respondents. Twenty-three respondents reported they would make changes in their practice after the workshop. Five respondents found the activity on roles and responses during socialization as needing more discussion. Key themes identified from the participants’ reflections were: (i) their different views about professional identity, (ii) experiences and reactions and (iii) their future action plan.

Conclusions

The workshop was well received by the participants. Our approach to the workshop might help other institutions design and implement similar activities as a part of their faculty development programme.

INTRODUCTION

Nursing professionals play an important role in delivery of care and healing of patients within healthcare systems. Gardner and Shulman have described six common characteristics of all professions: a commitment to serving clients and society, specialized knowledge and skills, the ability to make sound judgments under uncertainty, continuous learning from experience, and a community that maintains quality standards in practice and education.1 A comparative study of professional education in medicine, nursing, law, engineering and clergy from Carnegie Foundation is unequivocal in mentioning that the ‘common aim of all professional education is specialized knowledge and professional identity’.2 Benner et al. used various terms such as ‘formation’, ‘reformation’, ‘socialization’, and ‘acquisition of professional values’ to describe the concept of professional identity among nurses.3 They used the term formation as a description of developing skills and abilities of nursing and ‘a way of being and acting’.

One of the three major findings of the Carnegie report on education of nurses indicated that nursing programmes in the USA support the development of professional identity and ethical stance.4 However, the report identified a challenge in creating institutions and systems that promote professional attentiveness, responsibility and excellence, so that nurses understand that they have the authority, in addition to responsibility in nursing practice.

Some of the recommended strategies to support development of strong professional identity among nurses include institutional support, change in workplace culture and interprofessional education.5 Systems and policy level changes are required to break the nursing profession’s stereotype of being subservient to medicine.6

Though Indian Nursing Council has listed competencies of professionalism, professional values and ethics including bioethics, our literature search did not yield any discourse on professional identity formation (PIF) in Indian nursing education.7 Nursing institutions in India might leave PIF to chance without having educational systems and workplace policies to support PIF. Therefore, we decided to initiate a conversation with faculty of the Institute of Nursing at our university through a workshop regarding the concept of professional identity, factors influencing it and how best to support PIF. We report on the planning and conduct of the workshop, along with lessons learnt from the discussions in the workshop. The framework of the workshop and lessons learnt by us might be useful to institutions interested in conducting similar workshops.

METHODS

The workshop was conducted in November 2021 for faculty of the Institute of Nursing, a constituent institution of the university focused on healthcare education located in Gujarat, in western India. We used the framework suggested by Cruess et al. for designing the workshop.8 The knowledge building approach in this workshop was based on theories of cognitivism, constructivism and social learning.9 We conducted the workshop with the assumption that people do have prior experiences and they constantly navigate themselves within their immediate work and policy environment. We aimed to recall these experiences and help the participants to build knowledge and make associations between their prior experiences and the newer concepts introduced in the workshop.

Planning and implementation of the workshop

We conducted a meeting with the Principal of the Institute of Nursing to establish the need for conducting a workshop on PIF. A core group of 6 experienced faculty developed a 1-day workshop. The expected learning outcomes of the workshop were: (i) to understand the concept of PIF and process of socialization; (ii) to identify the factors influencing socialization; and (iii) to discuss strategies that support PIF.

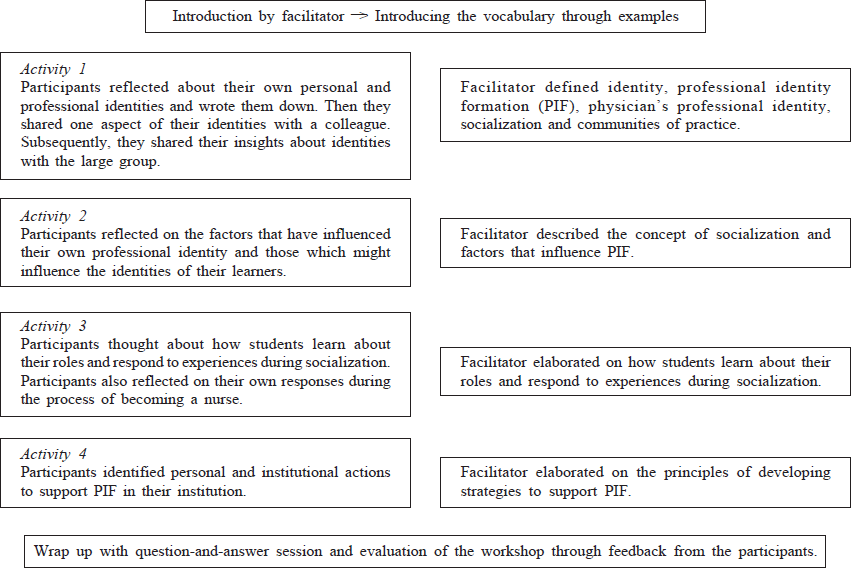

All 28 nominated participants (2 senior faculty, 7 middle-level faculty, 16 junior faculty and 3 postgraduate students) attended the workshop. The key resource faculty (first author) initiated the first group activity by listing his multiple personal and professional identities and gave an insightful personal account of his journey from being a clinical educator to an education leader. The workshop included a series of 4 small group discussions, each followed by debriefing. During debriefing, one of the facilitators steered the discussions to reinforce and expand the concepts of PIF and socialization in the context of their derived meanings. The key points of discussion were recorded. During the wrap-up, the facilitators invited participants to seek clarifications regarding the concepts of PIF (Fig. 1).

- Plan of workshop

A day after the workshop, we emailed 4 open-ended questions to obtain feedback from the workshop participants: (i) What was good about the workshop?; (ii) What could have been better?; (iii) What changes would you like to bring in your educational practice with students after this workshop?; and (iv) What points were unclear and need further clarification?. After the workshop, we asked participants to submit their written reflections on the learnings, within two days. Our institutional ethics committee granted exemption from review to this study.

Data and analysis

The data used for analysis were: (i) recorded key points; (ii) feedback questionnaire; and (iii) written reflections by the participants. We did a manual content analysis of text data generated during group work and feedback.10,11 The manual content analysis was done by the last author and reviewed by all the authors to bring interpretative credibility.10,11 The statements in square brackets in the results section are authors’ reflections during facilitation of the workshop. We did manual thematic analysis for participants’ reflections. As participants wrote reflections on their own, no transcription was necessary. We did thematic analysis as a group exercise among the facilitators as this was a more practical approach. Themes were developed in consensus. Statements in italics are slightly edited quotes from the participants. The descriptions of themes are provided in the results section.

RESULTS

Concepts about professional identity formation emerging during the workshop

Table I lists perceived personal and professional identities. Table II depicts explored factors influencing PIF. We observed that participants described what they learn through the process of socialization including the challenges of learning to play the role of nurse, the hierarchy and power relations in healthcare settings. They also shared their experiences of joy, pride, anxiety and stress during their PIF.

| Personal identity | Professional identity | |

|---|---|---|

| Daughter | Brother | Nurse |

| Mother | Sister | Care-giver |

| Wife | Husband | Teacher Role model |

| Enabling factors | Disabling factors |

|---|---|

|

|

Feedback on the workshop

Twenty-six of 28 participants responded to the questionnaire. Indicative responses of the study participants are shown in Table III. When asked what was good about the workshop, 13 of the respondents (50%) mentioned the interactions during group activities and discussions with facilitators, 9 referred to the group activity (34.6%), 8 to learning of body of knowledge (30.8%), and 4 about the method of the workshop (15.4%). Two participants reported explanation by the facilitators as the good part of the workshop, with 1 participant each reporting in-depth understanding and opportunity for self-introspection. The facilitators felt that participants had a casual approach to begin with. However, as the workshop unfolded, they became aware of the purpose of workshop and narrated personal stories and could make meaning of their experiences. The facilitators also felt that nurses participated with greater enthusiasm as compared to participation by physicians and physiotherapists in earlier workshops.

| Q1. What was good about the workshop? ‘Group activity can give us platform for sharing our views and ideas.’ ‘The group activities were best part in the workshop, due to which everyone got clear idea about professionalism. The... explanation by the speakers was really very good.’ |

| Q2. What could have been better? ‘It could have been 2-day workshop . some more time for discussion with presenter (facilitator)’ ‘Discussion time (should) be increased, otherwise, it was a very interesting workshop.’ |

| Q3. What changes would you bring about in your educational practice after attending the workshop? ‘Not only focus on academic achievement, but to develop an individual with holistic growth’ ‘Will arrange the same session for the final year students . to sensitize them and encourage them to practice so that they can help to inculcate the same in junior student(s).’ |

When asked about what could have been better, 8 respondents (30%) did not comment on what could have been better, however 5 (19.2%) said no change was required. Constructive suggestions were received from 13 respondents (50%). Fourteen (15%) requested more time for group work and discussions, and 2 others (7.7%) suggested increasing the duration of the workshop to 2 days. Two respondents (7.7%) felt a need for being provided pre-workshop reading material, handouts and literature. One respondent suggested that use of methods such as role play and videos would have been better. One respondent each suggested that more tasks and activities be added and more specific instructions be given for group work. There was one comment regarding expanding the scope of faculty development in the domain of professionalism. One of the participants suggested improving the sitting arrangement for better physical comfort.

When asked about possible changes in their educational practice post-workshop, 23 (88%) said that they would make changes in their practice after the workshop. Three (11.5%) said they would focus on development of students’ character in addition to providing academic support. Two respondents each (7.7%) reported they would sensitize students about PIF, provide encouragement to students, support students in the process of socialization, provide individual feedback on performance following assessment, use student-centric methods for teaching–learning, and review clinical tasks regularly. One participant each (3.8%) reported use of problem-based learning for teaching, incorporate situational learning, focus on improving students’ clinical skills, be more flexible in their approach with students, provide corrective feedback to students immediately, communicate frequently with students, improve their own communications skills, reflect on their own practice, strengthen the mentor–mentee programme and increase engagement in mentor–mentee relationships, and ensure a collegial learning environment.

When asked about points of clarification, 20 respondents (77%) said that no points needed clarification, 5 (19.2%) said that the activity on roles and responses during socialization was unclear, whereas 1 participant requested more information on the process of socialization during practice after graduation. (The facilitators also felt that activity 3 [Fig. 1] would have been better facilitated if it was preceded by personal narratives by the resource faculty in order to bring greater clarity about the activity).

Thematic analysis of participants’ reflections on the workshop Most participants felt that they enjoyed the workshop and learned new things regarding PIF. The major themes that emerged were:

-

Different views about professional identity. The reflection of different participants revealed that they have diverse ideas about the concept of professional identity.

P1: ‘Professional identity begins with the entry in that particular profession. It is a continuing and collective process’

P2: ‘Professional identity helps me as a nursing teacher to adopt qualities of a good nurse, which ultimately is all about showing kindness to someone’

-

Experiences and reactions. Most participants reported that their experience with the workshop was good as they gained knowledge and learned about the positive and negative factors influencing PIF.

P1: ‘This was a whole new concept for me to understand, learn and implement for students’

P5: ‘At the end of the workshop I gained much knowledge about PIF as well as socialization process in our profession’

-

Plan of action for future. Most participants said that they will be more focused from now on and will direct their behaviour in building up their learners’ professional identity. They also realized that burden of work and lack of sufficient time prevented them to achieve efficiency in several roles that they wanted to play in their professional practice. A few reported that they would take steps towards enhancing their leadership skills and motivate students to participate in group activities.

P1: ‘I will also take steps towards enhancing their leadership skills with the assignment of group activities.’

P6: ‘At that time I felt that there are several roles that I fulfil in my professional life and even there are several roles where I have yet to achieve; this was likely due to work burden, lack of sufficient time, etc.’

DISCUSSION

The participants’ feedback suggested that the workshop was successful in achieving Kirkpatrick levels I (satisfaction) and II (perceived learning). The participants were enthusiastic and ready to learn the concepts about PIF. The participants’ insights, and factors influencing professional formation were in alignment with the existing literature.12 The participants felt that digital distractions have emerged as a barrier to PIF. We designed this workshop based on the framework of Cruess et al.8 The narration of personal accounts by resource persons contributed to better understanding, by the participants, of the nature of the given tasks. We noted that guided reflections on their experiences of PIF helped them understand the construct of PIF; this might have been abstract otherwise.

Faculty development is an important strategy in teaching– learning of professionalism. Hence, faculty should not leave PIF to chance.8 Awareness among faculty about factors influencing socialization and their responses to the process of socialization is crucial in supporting PIF. We were able to increase awareness about PIF, process of socialization, and understanding about teachers’ and institutions’ role in supporting PIF. Based on our experience, we suggest such introductory workshops on PIF be preceded by sessions on professionalism. To reinforce the concept of PIF, additional topics such as role-modelling, mentoring and guided reflection may be included. However, a longitudinal faculty development programme would better achieve the learning outcomes.

The workshop was well received by the participants. Most participants developed an insight into the importance of developing a sense of self, the process of being and becoming a nursing professional, and felt motivated to support their learners in developing their professional identities. Our approach to the workshop might help other institutions design and implement similar activities for their faculty as a part of faculty development programme to support students’ PIF.

References

- The professions in America today: Crucial but fragile. Daedalus. 2005;134:13-18.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Educating lawyers: Preparation for the profession of law Indianapolis: John Wiley; 2007.

- [Google Scholar]

- Curricular and pedagogical implications for the Carnegie study, educating nurses: A call for radical transformation. Asian Nurs Res. 2015;9:1-6.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Educating nurses: A call for radical transformation Indianapolis: John Wiley; 2009.

- [Google Scholar]

- Interprofessional education: A perspective from India In: Waldman SD, Bowlin S, eds. Building a patient-centered interprofessional education program. Hershey, Pennsylvania: IGI Global; 2020. p. :259-85.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Role expectations and workplace relations experienced by men in nursing: A qualitative study through an interpretive description lens. J Advanced Nursing. 2020;76:1211-20.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- (2021) Revised regulations and curriculum for B.Sc. (Nursing) Program Regulations, 2020 Indian Nursing Council. Available at www.indiannursingcouncil.org/uploads/pdf/1625655521119217089560e588e166460.pdf (accessed on 2 Dec 2022).

- [Google Scholar]

- Teaching medical professionalism: Supporting the development of a professional identity New York: Cambridge University Press; 2016. p. :1-4.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Overview of current learning theories for medical educators. Am J Med. 2006;119:903-7.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- A step-by-step guide to qualitative data coding New York: Routledge; 2019.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- A schematic representation of the professional identity formation and socialization of medical students and residents: A guide for medical educators. Acad Med. 2015;90:718-25.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]