Translate this page into:

Teaching professional ethics to undergraduate medical students

Corresponding Author:

Sadaf Konain Ansari

D-986, 5th Road, Satellite Town, Rawalpindi 46300

Pakistan

sdf_ansari@yahoo.com

| How to cite this article: Ansari SK, Hussain M, Qureshi N. Teaching professional ethics to undergraduate medical students. Natl Med J India 2018;31:101-102 |

Abstract

Introduction

Medical ethics has progressively turned into a common element of the undergraduate curriculum at many medical institutes, often within a well-defined humanity programme.[1] ‘Professional ethics’ coaching can occur within the old model of medical teaching, where a distinct programme of scientific instruction follows several years of medical sciences.[2]

However, a vertically combined education model where clinical training runs integrated with basic disciplines may be better.[3] There is growing evidence that this improves undergraduates’ attitudes concerning patients,[4] delivers a structure for coaching assimilated scientific medicine[5] and improves learners for the clinical years.[6] Even though Islam has an extensive tradition of ethical thinking, there has been little incentive to start courses in ethics within the medical curricula in Pakistan.[7]

Educationists of the Royal College of Physicians of London have defined medical professionalism as ‘a set of values, behaviours and relationships that underpin the trust the public has in doctors, with doctors being committed to integrity, compassion, altruism, continuous improvement, excellence and teamwork’.[8]

The Need To Teach Professional Ethics

Autonomy, justice, beneficence and non-maleficence are the basis for healthcare professionals to guide and select what practices are appropriate.[9] These ethical philosophies are based on the Hippocratic Oath and Helsinki declaration.1σ Future doctors are expected to learn and abide by these moral values. This permits proper education of such philosophies; however, challenges persist in developing countries such as Pakistan, where a programme barely dictates the coaching of ‘medical professional ethics’.[11]

We propose one such longitudinal programme in the communication module which will run throughout the MBBS course in the Islamabad Medical and Dental College.[12]

The objective is to develop skilfully sound medical graduates in Pakistan who prosper for quality;[13] are ethical; approachable and responsible to patients, public and work, by experiencing training over a longitudinal course stretched through full MBBS programme and apply these philosophies of bioethics, professional competencies and ethical laws to deliver healthcare to patients.[1415]

Teaching Professional Ethics

Despite the emphasis on professional ethics, there are no definite guidelines on how it should be taught.[16] In many medical institutes, the acquisition of ethical values and behaviours is taught informally by role modelling and experiential learning throughout the undergraduate programme followed by residency and fellowship training.[17] Literature shows that multiple learning activities are used in different medical colleges for teaching ethics. These activities are either concentrated in a single course or are spread throughout an integrated curriculum.[18] The key teaching and learning activities identified in the literature for this purpose include:[19]

- Experiential or reflective practice

- Clinical contact with tutor feedback

- Interactive seminars and lectures

- Problem-based learning

- Role play exercises

- Bedside teaching

- Educational portfolios

- Videos

- Significant event analysis

- Mentoring programmes

Teaching and Assessing Professional Ethics of Communication Skills

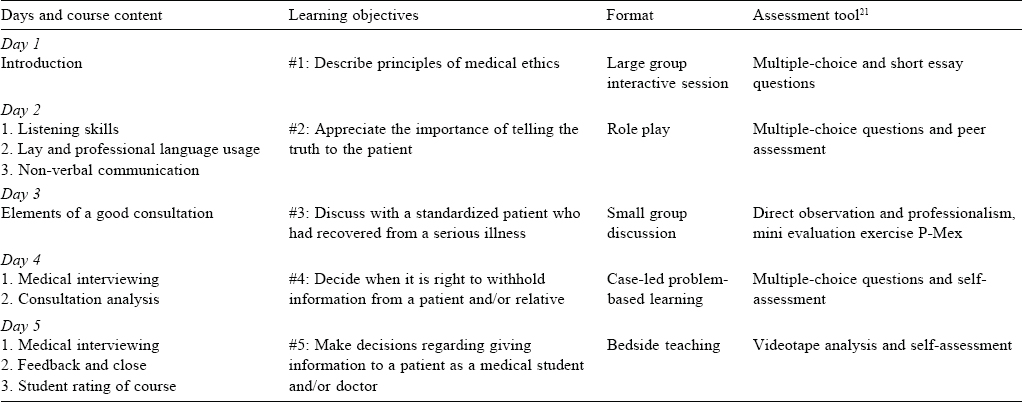

Apart from these, for third year MBBS, we chose large group interactive lectures, small group discussions, role play, case-led problem-based learning and bedside teaching to achieve ' specific, measureable, achievable, relevant, time-bound’[6] communication skills’ module learning with outcomes [Table - 1].

Teaching these components of communication skills to third year MBBS students is important to build respectable, trustable relationships with patients and understand patients’ perception of disease.[22]

Conclusion

We found that role play and mentoring programmes are indeed reflective sessions for teachers to improve their communicative processes involved in actual medical practice,[23] resulting in an improved sense of communicative competency and influence their personal development. This indeed is a concept of ‘personal meaning’ and ‘responsibility’.[24] Once there is balance between ethics and law with inner satisfaction of one’s own choice of decision, then the professional identity has been identified as ‘practical wisdom’.[25] Moreover, as medical educationists, their identity will be ‘to give real service, they must add a little more, which cannot be bought or measured with cash, and that is; sincerity, honesty and being humane’.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Dr Mohammad Al-Eraky, Professor of Medical Education, University of Dammam, who guided us in making this course and format of learning and assessment of communication skills component of professional ethics. We are also thankful to Dr Salma Zafar, Associate Professor of Microbiology, Islamabad Medical and Dental College, who helped us in refining these learning objectives.

Conflicts of interest. None declared

| 1. | Khalid F, Usman M, Rahila Y. Teaching professional ethics to undergraduate medical students. JIIMC 2015;10:45–7. [Google Scholar] |

| 2. | Glick SM. Teaching medical ethics symposium. The teaching of medical ethics to medical students. J Med Ethics 1994;20:239^3. [Google Scholar] |

| 3. | Mousavi S. Usage ethics in medical education in Islamic countries. Q J Med Ethics 2008;2:143–54. [Google Scholar] |

| 4. | Taylor SJ. Doing right: A practical guide to ethics for physicians and medical trainees. Can Med Assoc J 1997;156:417-18. [Google Scholar] |

| 5. | Snelgrove R, Ng S, Devon K. Ethics M&Ms: Toward a recognition of ethics in everyday practice. J Grad Med Educ 2016;8:462–4. [Google Scholar] |

| 6. | Hutchings T. Protecting the Profession-Professional Ethics in the Classroom; 2016. Available at www.ets.org/s/proethica/pdf/real-clear-articles.pdf (accessed on 1 Mar 2017). [Google Scholar] |

| 7. | Aldughaither SK, Almazyiad MA, Alsultan SA, Al Masaud AO, Alddakkan ARS, Alyahya BM, et al. Student perspectives on a course on medical ethics in Saudi Arabia. J Taibah UnivMed Sci 2012;7:113–17. [Google Scholar] |

| 8. | Konkin J, Suddards C. Creating stories to live by: Caring and professional identity formation in a longitudinal integrated clerkship. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract 2012;17:585-96. [Google Scholar] |

| 9. | American Chemical Society. Committee on Professional Training Supplement on the Teaching ofProfessional Ethics. American Chemical Society; 2015:1-2. Available at www. acs. org/content/dam/acsorg/about/governance/committees/training/ acsapproved/degreeprogram/guidelines-for-the-teaching-of-professional- ethics.pdf?_ga=1.84696857.1498353767.1472068756 (accessed on 1 Mar 2017). [Google Scholar] |

| 10. | Hilton SR, Slotnick HB. Proto-professionalism: How professionalisation occurs across the continuum of medical education. Med Educ 2005;39:58-65. [Google Scholar] |

| 11. | Aschenbrener CA, Ast C, Kirch DG. Graduate medical education: Its role in achieving a true medical education continuum. Acad Med 2015;90:1203-9. [Google Scholar] |

| 12. | Gondal GM. Role of teaching ethics in medical curriculum. Found Univ Med J 2014;1:47–9. [Google Scholar] |

| 13. | Riley S, Kumar N. Teaching medical professionalism. Clin Med (Lond) 2012;12:9–11. [Google Scholar] |

| 14. | Selwyn S. Islamic medicine. J R Soc Med 1978;71:932–3. [Google Scholar] |

| 15. | Padela AI. Islamic medical ethics: A primer. Bioethics 2007;21:169–78. [Google Scholar] |

| 16. | Joekes K, Noble LM, Kubacki AM, Potts HW, Lloyd M. Does the inclusion of ‘professional development’ teaching improve medical students’ communication skills? BMC Med Educ 2011; 11:41. [Google Scholar] |

| 17. | Shakir R. Soft skills at the Malaysian institutes of higher learning. Asia Pac Educ Rev 2009;10:309-15. [Google Scholar] |

| 18. | Cruess SR, Cruess RL. Teaching professionalism—Why, what and how. Facts Views Vis Obgyn 2012;4:259-65. [Google Scholar] |

| 19. | Professionalism in Healthcare Professionals. Available at www.hcpc-uk.org/ globalassets/resources/reports/professionalism-in-healthcare-professionals.pdf (accessed on 1 Mar 2017). [Google Scholar] |

| 20. | Collste G. Applied and professional ethics. Kemanusiaan 2012;19:17–33. [Google Scholar] |

| 21. | Hodges BD, Ginsburg S, Cruess R, Cruess S, Delport R, Hafferty F, et al. Assessment of professionalism: Recommendations from the Ottawa 2010 conference. Med Teach 2011;33:354-63. [Google Scholar] |

| 22. | Cruess SR, Cruess RL, Steinert Y. Linking the teaching of professionalism to the social contract: A call for cultural humility. Med Teach 2010;32:357-9. [Google Scholar] |

| 23. | Wald HS. Professional identity (trans)formation in medical education: Reflection, relationship, resilience. Acad Med 2015;90:701-6. [Google Scholar] |

| 24. | Nortvedt P. Medical ethics manual: Does it serve its purpose? J Med Ethics 2006;32:159–60. [Google Scholar] |

| 25. | Goldstein PA, Storey-Johnson C, Beck S. Facilitating the initiation of the physician’s professional identity: Cornell’s urban semester program. Perspect Med Educ 2014;3:492–9. [Google Scholar] |

Fulltext Views

5,811

PDF downloads

2,273