Translate this page into:

The Australian Medical Journal, August 1846

Correspondence to ANANTANARAYANAN RAMAN; anant@raman.id.au; Anantanarayanan.Raman@CSIRO.au; araman@csu.edu.au.

[To cite: Raman R and Raman A. The Australian Medical Journal, August 1846. Natl Med J India 2023;36:263–8. DOI: 10.25259/NMJI_389_22]

Abstract

Medical journals started appearing formally in Europe in the 17th century and in North America in the 18th century. In Australia, the first issue of Australian Medical Journal (AMJ) was issued in Sydney, under the stewardship of a New South Wales (NSW) senior surgeon William Brooks working in Newcastle (NSW) in August 1846. This article refers to that issue of AMJ exploring its contents and context. In terms of original articles, only one on the surgical procedures carried out on two patients suffering strangulated hernias in the Parramatta-Public Hospital by Surgeon Thomas Robertson occurs. The other inclusions are précis from contemporary British medical journals. The AMJ appeared only for a year; why it ceased publication in 1847 is not clear. It was resurrected by the Medical Society of Victoria, Melbourne in 1856, issuing 40 annual volumes uninterruptedly until 1895. With the incorporation of other regional Australian medical journals, AMJ was re-named as the Medical Journal of Australia (MJA) in 1914. As MJA, it continues to perform to-date. Natl Med J India 2023;36:263–8

INTRODUCTION

Professional medical groups in Australia (Note 1) existed from early 1800s, but they identified themselves as branches of the British Medical Association (BMA), e.g. ‘BMA-New South Wales’, ‘BMA-Victoria’ (Note 2). The BMA branches in Australia merged to constitute a single professional group throughout Australia, viz. the Australian Medical Association in 1962.

THE AUSTRALIAN MEDICAL JOURNAL

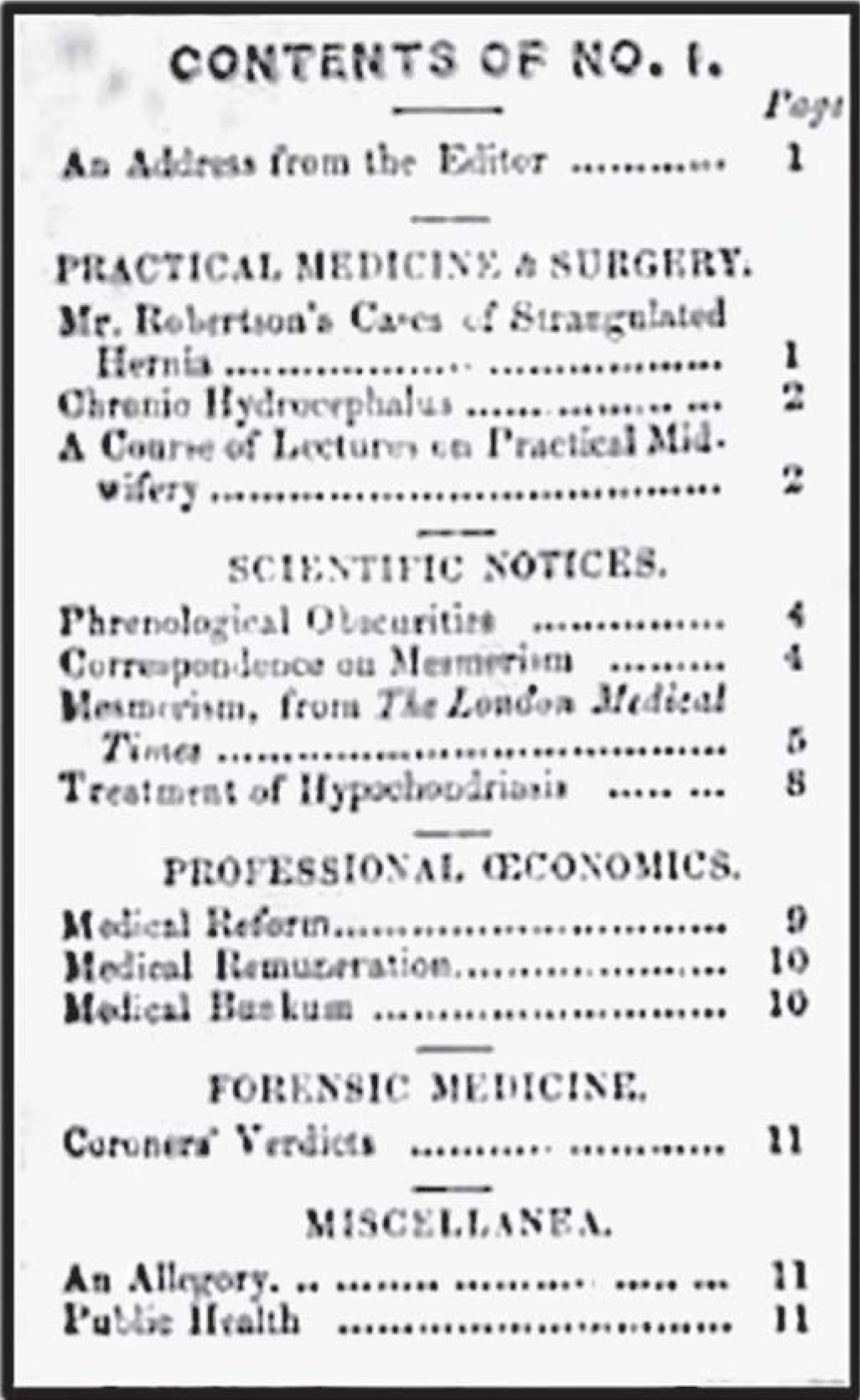

The Australian Medical Journal (AMJ) was launched in Sydney (NSW) on 1 August 1846 made of 16 sheets printed in tabloid format (17x11 inches; 43.18x27.94 cm). Highly likely this was initiated by the BMA-NSW. We surmise it so, since nowhere this detail is indicated. Every page consists of three tightly arranged columns (Fig. 1). The layout of this issue of the AMJ is largely similar to the layout of the Medical Times (A Journal of English and Foreign Medicine and Miscellany of Medical Affairs), printed, published and distributed by Julius Angerstein of Carfrae, London (Fig. 2). The cover page of the first issue of AMJ includes a prospectus, a general notice, and details of movements of ships in and out of Sydney port (Note 3). This column continues on the reverse, followed by annotations from the Acts of the Council and the Parliament of New South Wales, possibly relevant to AMJ readers of that time. The reverse of the cover page also includes a few line- advertisements pertaining to diverse aspects of the printing industry—probably, to generate revenue. The succeeding page numbered ‘1’ includes a table of contents of this issue (Fig. 3).

- Cover page of the Australian Medical Journal, 1 August 1846

- The cover and first pages of The Medical Times (Volume 11, 1844–1845) from London, possibly from 1835

- Contents (page 1, AMJ, 1 August 1846)

PROSPECTUS AND GENERAL NOTICE

A prospectus (indicated as ‘An address from the editor’ in the table of contents) on page 1 introduces the purposes of AMJ— subsequently referred as ‘objects’—clarifying that AMJ would appear on the first day of every month. William Baker (Secretary, Medical Board of NSW and a lithographer in Pitt Street, Sydney) (Note 4) and George Brooks (Colonial Surgeon in Newcastle, NSW) (Note 5) are indicated as the printer and editor, respectively. The scope of the journal is:

… will contain Treatises on Diseases of the colony (NSW), Intelligences (news, information received, imparted) selected from recent Publications, and Information of every kind useful to the Profession.

In this prospectus, editor Brooks seeks the cooperation and participation of every medical practitioner to contribute to AMJ:

But in order that these objects be successfully accomplished, Medical Practitioners, and all persons interested in that and its subordinate Sciences, are respectfully reminded that the Healing Art is essentially progressive; and that as a vehicle of isolated discoveries, and of passing events, the Journal cannot be very useful without extensive co-operation.

Details of potential circulation are available in this section. A notice, placed at the end of the prospectus, calls publishers of contemporary medical journals to send copies of their published issues in exchange for AMJ issues sent gratis to them. This prospectus indicates,

… a thousand copies of the first number, in the new form, will be dispersed gratuitously ...

The words ‘new form’ in this sentence-fragment prompted Norman James Dunlop (Honorary Surgeon, Colonial Hospital, Newcastle, NSW)1 in 1927 to suspect whether a medical journal existed before the AMJ issue of August 1846, either in NSW or elsewhere in Australia. Gwenifer Catherine May Wilson (1916– 1998), a specialist-anaesthetist in Sydney, and later a full-time medical historian, clarifies in the 1977-Ernest Sandford Jackson (Note 6) Lecture2 that ‘new form’ refers to the use of a new kind of typefaces and machine printing in striking copies of AMJ. Wilson confirms that the AMJ published in August 1846 was the first formal medical periodical in Australia. We have chosen to disregard the section ‘Shipping Intelligence’ deliberately, because of its irrelevance to the present-day readers and especially those of the National Medical Journal of India (NMJI).

PRACTICAL MEDICINE AND SURGERY

This section consists of three parts and occurs from the middle of the 2nd column, page 1 to the middle of 3rd column, page 4. The first is a letter to the editor (a ‘case report’?) dated 23 April 1846 on ‘strangulated hernias’ by Thomas Robertson (Note 7), Colonial Surgeon, Parramatta-Colonial Hospital (PCH), Parramatta (Note 8). The second refers to chronic hydrocephalus, and the third to a lecture-series delivered on practical midwifery in the UK. The second and the third are précis of articles published elsewhere. Robertson’s letter referring to hernia surgeries and postoperative care of his two patients: (i) William Adams and (ii) an unidentified person, is likely the single original contribution to this issue of AMJ. Robertson surgically treated William’s inguinal herniation and the unidentified patient’s impacted herniation. In this letter, Robertson speaks in considerable detail of the procedure he followed to treat William from 23 January 1846 (the date of surgery) until discharge from the hospital on 7 March 1846. Following Robertson’s letter, an essay on strangulated hernias treated elsewhere in NSW occurs with no details of writers. A paraphrased report on the surgical procedure on acute hydrocephaly on a 3-month-old baby done by John Fife (1795– 1871, Surgeon, Newcastle-upon-Tyne Infirmary, UK) follows Robertson’s letter. The reproduced report of Fife refers to a previously published work in the Provincial Medical & Surgical Journal (PMSJ) (Note 9)—1840, indicated as the Provincial Medical Journal. Towards the end of this paraphrased report, a query occurs, reproduced below, in high probability raised by Brooks (p. 2):

We have seen, but not in this country (does this mean Australia? Or the colony of NSW?), a case of greater magnitude than this. The boy was about ten years of age, and the circumference of the head was thirty-three inches. He died, and we believe without any annual attempt to relieve him. It must be obvious that delay is peculiarly dangerous in these cases. A favourable result, where surgical means are used, must greatly depend upon the degree in which the cranium is compressible: and when we consider to how great an extent the encephalon and its membranes may be injured, without fatal consequences, there appears good reason to evacuate, at an early period after the chronic character of the disease is established. Are we right in considering this a remarkably uncommon disease in this Colony?

Another paraphrased report on a course on practical midwifery conducted by Edward Rigby Jr (1804–1860, a gynaecologist–obstetrician, St Bartholomew’s Hospital, London)3, extracted from the London-based London Medical Times follows. What is indicated as the London Medical Times should be the Medical Times, London, previously clarified in the present article.

SCIENTIFIC NOTICES

This section (from the middle of 3rd column, page 4 to the middle of 2nd column, page 8) includes (i) phrenological obscurities; (ii) mesmerism; and (iii) treatment of hypochondriasis. The notice pertaining to phrenology evokes curiosity because this presently obsolete discipline relates—rather intriguingly—the design and structure of human crania to mental faculties and characters of humans. Phrenology was developed as a scientific discipline by the neurologist Franz Joseph Gall (1758–1828) from Baden Württemberg, Germany. Phrenology was popular until the end of the 19th century but got rejected as a pseudoscience in the early 20th century (Note 10). The phrenology feature in this issue of AMJ refers to the cranial structure and design of an Irish criminal John A’Hearn of the 19th century. The original source of this piece of information is not supplied. The notice on mesmerism is long (49 pages) and includes a letter in support of mesmerism by someone signed as ‘Investigator’ and a rebuttal to that letter by another signed as ‘Vindicator from Leicester’ dated 28 December 1844. Follow- ing these letters, a summary of several publications of John Braid (1795–1860), a Scottish surgeon practising in Manchester, UK, made in the Medical Times, London (1844–1845) pertaining to ‘mesmerism, hypnosis, and hypnotherapy’ is available. In this section a few positive remarks—possibly by the editor of AMJ—exist, reproduced below (p. 8):

These two sections—the one descriptive of the effects (of mesmerism)—p. 8. The other explanatory of the philosophy of mesmerism—present that mystical subject in a shape more deserving to be entertained, by the judgment of the sober minded, than any treatise which we have hitherto met with, while they possess the substantive recommen- dation of personal reference.

Mr Braid’s reasonings produce a degree of satisfaction which must be particularly acceptable to those, who, disgusted by the frauds of performers have not allowed themselves to bestow a serious thought upon mesmerism. His ingenuity, and perseverance, in bringing this hitherto impalpable art within the province of common sense, are admirable. Attempts have been made by others, and not without success, to explain some of its influences by means of the principles of positive science, but we do not know any others than Mr. B (i.e., James Braid) has prodecuted them in detail; and therefore, propose to continue his disseration in succeeding numbers.

The section on mesmerism reminds us of the efforts of Franz Anton Mesmer (1734–1815) of Vienna—the proponent of ‘animal magnetism’ that later became ‘mesmerism’—made in 1779. Mesmerism was the forerunner of hypnosis and was practised in continental Europe and England in pain management and during surgical procedures before the advent of chemical anaesthetics (e.g. N2O). Mesmerism was used in surgeries by the colonial-period British doctors in India. For instance, Joseph William Turner Johnstone (?1848), an ‘M.D.’ holder from Scotland practising in Madras in the 1840s, successfully excised a large, lipomatous tumour from the upper dorsum–shoulder junction of a woman, after mesmerizing her.4 The last segment of the section Scientific Notices in AMJ alludes to the explanation of the anxiety disorder hypochondria by Claude-François Michéa (1815–1882) (Marcel-Sainte-Colombe Hospital, Paris; founding Secretary of la Société Médico-Psychologique Française) made in 1845. From a brief prologue that follows— obviously written by editor Brooks—we understand that this text is also reproduced from a previous issue of Medical Times, London. This section ends with ‘to be concluded’.

PROFESSIONAL ECONOMICS

This section (from the middle of the 2nd column, page 9 to the middle of the 1st column, page 11) is presented in three parts: (i) medical reform; (ii) medical remuneration; and (iii) medical bunkum. The first, ‘medical reform’, popularly Sir James Graham’s Medical Bill tabled at the House of Commons, London, is a reproduction from the Medical Times of London, seeking a better regulation of medical practice in the UK. This bill was announced at the House of Commons on 22 August 1844 by James George Robert Graham (1792–1861, Secretary of State for the Home Department).5 Details presented in the columns on medical remuneration and medical bunkum, we think, are irrelevant to the modern medical context and especially to the readers of the NMJI. ‘Bunkum’ used here triggers a chuckle.

FORENSIC MEDICINE (CORONER’S VERDICTS)

This section (second half of column 1 in page 11) is a sharply worded, brief critique referring to the wording of verdicts delivered in the Coroner’s Courts of NSW. This unsigned critique particularly refers to words ‘death from natural causes’ used frequently in Coroner’s reports, implying that the death is not due to any criminal violence. The writer of this feature vehemently criticizes the vagueness in such a remark and challenges that ‘deaths due to natural causes’ can be best assigned to convulsions (grand-mal seizures resulting in the obstruction of trachea and eventually in sudden death) and heart diseases. This section concludes suggesting an alternate set of wording for use by Coroner’s Courts.

MISCELLANEA, ALLEGORY

The 2nd column in page 11 referring to the above subject is intellectually challenging. Derived from Greek (ëëïò [allos] + áãïñåõåéí [agoreuein]), the English term ‘allegory’ means systematic symbolism used in the form of either an extended metaphor or a figurative description to convey a moral message in a disguised language.6 This section alludes to deep worldviews of science and especially that of medicine, but said in a convolute Victorian-era prose, supplemented with quotations from Edmund Waller (1606–1687, English writer and politician), Alexander Pope (1688–1744, English poet and satirist) and Walter Scott (1771–1832, Scottish thinker).

Alexander Pope’s (1688–1744) verse (published post- humously, 1786) used at the end of this section

Order is Heaven’s First Law; and this confest, Some are, and must be, greater than the rest, More rich, more wise, but who infers from hence That such are happier, shocks all common sense.

speaks of the identical nature of pleasure and pain in humans. In the cited-verse, Pope concedes that pleasure and pain do not exist in measurable, outwardly manifest dimensions; but they exist indiscernibly, working either in synchrony producing an inner balance or in asynchrony producing an inner imbalance. Pope’s message is that a human presenting outward happiness could be inwardly distressed; the reverse, according to Pope, is an intrinsic possibility as well.

Citing words of Scott ‘Wheel dune little Wheelje, Muckle wheel canna catch’ee’, the editor of AMJ remarks,

We wish, therefore, that the little wheel had made less noise and dirt; we regret that it was not satisfied with the greater responsibility of its position, and that it did not await vindication in the result of the proceedings.

Edmund Waller’s ‘circles are praised not, that abound in largeness, but the exactly round’ occurs in this section possibly implicating the universal symbolism of a circle as a representation of totality, wholeness, the infinite, eternity, and timelessness. Exploring the words of Waller, the editor of AMJ reminds readers that only quality matters, and not quantity.

PUBLIC HEALTH

This section running from column 3 of page 11 to the end of page 12 refers to a 351-page long report submitted by a 13-member commission,7 appointed by the British Government inquiring into the state of large towns and populous districts in England. At the start occurs ‘Taken from the London Medical Times (=the Medical Times of London)’ and a second one ‘For the benefit of the inhabitants of Sydney’. At the end of page 12, it concludes with a note ‘to be continued’.

THE LAST TWO UNNUMBERED PAGES

The last two unnumbered pages after page 12 include a variety of line-ads intermixed with a report from the Coroner of the Districts of Sydney and Parramatta. The line-ads provide an interesting reading, especially as the year was 1846. Printer William Baker has included a line-ad about a book that lists the legally qualified medical practitioners of NSW. Yet another one refers to an ‘in-press’ announcement of the report of the German-natural historian and explorer Ludwig Leichhardt (Note 11). On the last page, a few announcements on the births, deaths and marriages occur. Two box advertisements by Ambrose Foss (Pitt Street, Sydney) and P.F. Morgan (also Pitt Street) (Fig. 4) referring to their pharmacies, referred as ‘Chemist & Druggist’ (Note 12), occur in this page.

- Box advertisement by P.F. Morgan, Chemist & Druggist

REMARKS

One hundred and seventy-seven years have passed since the first issue of AMJ. Obviously the AMJ, starting with the issue launched on 1 August 1846 aimed at filling an academic gap further to enabling professional development of the medical personnel of NSW and perhaps that of Australia. However, just one ‘case report’ by the Parramatta Surgeon Thomas Robertson on strangulated hernia he conducted in the Parramatta-Public Hospital fills the category of an ‘original-scientific paper’. The remainder pertains to information extracted from contemporary British medical journals.

One curious, but striking element in this issue of AMJ—also common in other medical and science journals published in the rest of the world at that time—is the preference for anonymity by writers. A present-day reader would be baffled reading sharp remarks made by an anonymous person inserted within many pieces in this issue of AMJ. In most instances, we—the authors of the present article—guessed those remarks were by Brooks, since only his name occurs as the author persona of this issue. Moreover, in the piece on mesmerism, pseudonyms ‘indicator’ and ‘vindicator’ occur. The preference to stay anonymous is common among writers of fiction even today. Isaac Asimov (1920–1992, American-science writer and biochemist) wrote many articles as ‘Paul French’. Charles Lutwidge Dodgson (1832–1898), the author of Alice’s Adventures in the Wonderland, wrote as ‘Lewis Carroll’. Two reasons explain anonymity in such circumstances: first, decisions of authors, editors, and/or publishers; second, the author was either originally unknown or became less-known over time. Whatever be the reason, anonymity and pseudo-anonymity are fiddly and even difficult to relate and make convincing connections— from a chronicler’s viewpoint. The main argument here is that while analysing a narrative published in an old-science journal, we—the present-day readers—are keen to understand the steering philosophy of the journal on the one hand and relate that to the personal philosophy of the people who wrote in that journal on the other. Anonymity and pseudo-anonymity are unhelpful in relating them sensibly.

Many remarks embedded within various paraphrased sections in this issue of AMJ were probably by William Brooks the editor. Especially the quotes from Alexander Pope, Walter Scott and Edmund Waller in the feature ‘allegory’ offer stimulating reading. But this section is presented in Victorian- period prose and therefore demands repeated readings to grasp the message; tiring and frustrating. Being a medical journal, AMJ’s focus is definitely on human ‘wellness and illness’ and ‘health and disease’.

Until the end of the 18th century, medicine and medical practice in the West were seen from a Romantic perspective.8 However, the positivistic worldview advanced by the French mathematician–thinker Auguste François Comte (1798–1857) replaced the Romantic worldview of medicine in the 18th century. For example, a Berlin-based medical practitioner, historian, and philosopher Julius Leopold Pagel (1851–1921), a strong subscriber to positivism, considered the term ‘philosophy-of- medicine’ an oxymoron.9 To Pagel and other positivists, preoccupation with theory was hopeless, especially when problems of the sick had to be dealt with as speedily as possible. Such a positivistic thinking sharpened the fundamental principle of western-medical practice to ‘rapid-pain-alleviation’. The pain site, therefore, became the focal point of immediate attention to the physician: symptoms led to diagnosis and diagnosis led to therapy and cure. In contrast, the Eastern-medical practice (e.g. Indian Ãyûrvédã, Chinese acupuncture) reinforces not on rapid-pain-alleviation, but takes a whole-body consideration approach, since its foundation principle is ‘whole-body balance’. The Ãyûrvédã posits that a balance among the humors—blood, bile, phlegm—enables the maintenance of sound health; illnesses manifest because of either excesses of or deficiencies in one or more humors. With a better understanding of human anatomy, bolstered by Francis Bacon’s (1561–1626) inductive reasoning,10 the focus of western medical philosophy shifted towards biological fitness—survival and procreation—as the sole purpose of human life.11 Improvement of chances of human survival and the ability to reproduce successfully became the cardinal themes. Rapid-pain-alleviation climbed to the centre- stage in the post-18th century western medical practice, shifting to reductionistic worldview, whereas the eastern medical thinking and practice remained, and continue to remain, committed to holism. Modern western medical practice stands on a reductionistic pedestal, relying on both the ‘obvious’ and the ‘obscure’. The reductionism–holism debate in medical practice is ongoing, given that many modern philosophers of western medicine12 argue in favour of holism.

Back to the feature ‘allegory’ in this issue of AMJ. The purpose of this feature is not clear. We—the authors of the present article—guess that it was intended to alert and stimulate readers of AMJ to become sensitive to the relevance of medical theory against practice, given that the positivistic viewpoint emphasizing that preoccupation with theory is hopeless was beginning to take over medical practice rigorously in mid-19th century. Brooks must have intended the allegory in AMJ as an ‘editorial’. In actuality, any scientific theory in an empirically driven world of observation and experience necessarily requires constant verification and re-verification. This process of verification enables practitioners to develop generalizations and achieve clarity; the repeated verification process empowers practitioners to forecast what might occur in similar contexts and situations at different points of time. Lack of generalizations and clarity will necessarily provoke practitioners to re-invent the wheel every time when they get entangled in a glitch—in the present context, in a clinical glitch. Most likely, that was the intent of William Brooks for this complexly worded allegory.

THE AUSTRALIAN MEDICAL JOURNAL TODAY

The AMJ printed and published by William Baker of Sydney and edited by Surgeon William Brooks of Newcastle (NSW) in August 1846 ceased publication in 1847. No details explain with which issue did AMJ cease publication in 1847 and why did it cease. The AMJ was resurrected by the Medical Society of Victoria, Melbourne (MSV–M), publishing 40 volumes (123 from 1856 to 1878; as a New Series 117 from 1879 to 1895) uninterruptedly. A page-and-a-quarter long review of the relaunched first issue of AMJ of 1856 is available in the British and Foreign Medico-Chirurgical Review of 1856.13 This review clarifies that the re-issued AMJ was changed to a quarterly. In 1896, AMJ incorporating the Intercolonial Quarterly Journal of Medicine and Surgery (Note 13), edited by an editorial team of MSV–M (no names available) appeared. Subsequently the AMJ incorporated the Australasian Medical Gazette (Note 14) published from Sydney (1881–1914) and emerged with a new name: the Medical Journal of Australia (MJA) from 1914 (MJA history, www.mja.com.au/journal/mja- history, 24 May 2023; Fig. 5). MJA is continuing to-date, going strong.

- Cover page of the 24 March 1923 issue of AMJ, re-born as the Medical Journal of Australia, Sydney (Source: https://archive.org/details/sim_medical-journal-of-australia_1923-03-24_1_12/page/n1/mode/2up)

Notes

Terra Australis was the earliest term used by the British expeditioner Matthew Flinders (1774–1814) referring to the Australian continent. After colonization of this landscape in 1768–1771, independent colonies of New South Wales (NSW), Queensland (QLD), South Australia (SA), Tasmania (=van Diemen’s Land. TAS), Victoria (VIC), and Western Australia (WA) existed until 1901. The colonies of NSW, VIC, QLD, SA, WA, TAS merged as ‘states’ forming the Commonwealth of Australia, further to the newly carved territories, the Northern Territory (NT) and Australian Capital Territory (ACT), with Edmund Barton taking over as the Prime Minister in January 1901. Intelligence: knowledge of events; information communicated specifically of military value (Oxford English Dictionary). Available at www.oed.com/viewdictionaryentry/Entry/95568 (accessed on 11 May 2023). Dublin-born William (Kellett) Baker (1807–1857), a popular printer, engraver, lithographer, and a specialist copperplate printer in Sydney was the printer (publisher, as well?) of AMJ. Edinburgh-born Brooks (b. 1798) started his life as an assistant surgeon in Sydney (NSW) in 1819. He was promoted as the Colonial Surgeon (full Surgeon) in Newcastle in 1829. He died in 1854. Ernest S. Jackson (1860–1938) was a physician at the Brisbane Hospital, Brisbane, Queensland from 1898. Further to being a doctor in Brisbane, he is remembered for the history of marine exploration and medicine. Thomas Robertson born in Aberdeen in 1823, arrived in Sydney as a ship surgeon. He was a medical practitioner in Parramatta, then a growing suburb of Sydney. The Parramatta History and Heritage web page (Available at https://historyandheritage.cityofparramatta.nsw.gov.au/, accessed on 13 May 2023) speaks of Robertson as the Honorary Surgeon at the Parramatta-Colonial Hospital (PCH). Robertson was popular in surgically treating hernias. Robertson played a vital role in the formation and growth of the PCH (established in 1846), which metamorphosed as the Parramatta District Hospital in 1848, and the Westmead Hospital in 1978 (Available at https://historyandheritage.cityofparramatta.nsw.gov.au/, accessed on 13 May 2023). Parramatta is 25 km west of Sydney CBD, the second European settlement in Australia, was established as an outlying farm colony of Sydney by Governor Arthur Phillip in 1788. Initially this region was known as the Rose Hill, renamed as Parramatta—an Aboriginal word for the head of waters—in 1790. The PMSJ, edited by Peter Hennis Green and Robert James Nicholl Streeten, was administered by the Provincial Medical and Surgical Association of London (1832) established under the presidentship of Charles Hastings of the Worcester Infirmary (Western Midlands, near Birmingham). Pertinent it would be to recall the encyclopaedic work Castes and Tribes of Southern India14 resulting from the extensive study of nearly all the social clusters of the Presidency of Madras, and the princely states of Travancore, Mysore, Coorg, and Pûdû-k-kôttai by Edgar Thurston (1855–1935), superintendent of Madras Museum (1885–1908) and a trained medical doctor, co-written with botanist Kadambi Rangachari (1868–1934) of the Madras Museum in 1909. In this 7-volume book Thurston and Rangachari explore the early European thoughts on phrenology to assess and determine the intellectual capabilities of southern Indians. They also use ‘anthropometric measurements’—a modestly better and more-refined technique, developed by Louis-René Villermé (Paris) and promoted by Adolphe Quetelet (Brussels),15,16 respectively. Thurston was of strong conviction that the level of intelligence was inversely proportional to ‘nose width’(!). During his stay in Madras, he lectured at the University of Madras and to Madras Police on practical anthropology in the 1890s. Thurston also trained the Madras Police personnel in using anthropometry in identifying criminals.17 Friedrich Wilhelm Ludwig Leichhardt (1813–1848-?) was a naturalist from Oder Spree in Brandenburg, Germany, famous for his exploration and mapping of northern and central Australia. The present-day common use of the term ‘pharmacy’ was first used in the US, whereas the term ‘Chemist & Druggist’ persisted in the UK and British colonies until the 1950s. A ‘College of Pharmacy’—an exclusive institution for pharmacist trainees—opened in Philadelphia in 1821. This institution maintained the Journal of the Philadelphia College of Pharmacy in 1825, which transformed as the American Journal of Pharmacy in 1835. Intercolonial Quarterly Journal of Medicine and Surgery (1895–1896) changed names with time: Intercolonial Medical Journal of Australasia: 1896–1909, Australian Medical Journal: 1910–1914, Medical Journal of Australia: 1914– present. The Australasian Medical Gazette (AMG) was the journal of the combined Australian Branches of the British Medical Association. The BMA–NSW published AMG in 1895–1914. In 1897, the New Zealand Medical Journal was incorporated with AMG.

References

- An essay relating chiefly to anaesthetics and their introduction to Australia and Tasmania. Sydney:The Australasian Medical Publishing Company 1927

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The pioneering anaesthetists of Australia: Ernest Sandford Jackson Lecture, 1977. Anaesth Intensive Care. 1979;7:311-21.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dr Edward Rigby, Junior, of London (1804-1860) and his system of midwifery. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2001;84:F216-F217.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A painless surgery Joseph Johnstone performed on a mesmerized patient in Madras in 1847. Ind J Hist Sci. 2019;54:1322.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Sir James Graham's medical bill. Prov Med Surg J. 1844;8:35-57.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First report of the commissioners for inquiring into the state of large towns and populous districts. Her Majesty's Stationery Office, London. Volume I:18-44.

- [Google Scholar]

- Romantic medicine: A problem in historical periodization. Bull Hist Med. 1951;25:149-58.

- [Google Scholar]

- Einführung in die Geschichte der Medizin in 25 akademischen Vorlesungen (K. Sudhoff, ed) Berlin: S. Karger; 1915.

- [Google Scholar]

- Medical reductionism: Lessons from the great philosophers. QJM: Inter J Med. 2010;103:721-4.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Recherches sur la loi de croissance de l’homme. Ann d’Hyg Publ Med Leg. 1831;6:89-113.

- [Google Scholar]

- The crimes of colonialism: Anthropology and the textualization of India In: Pels P, Salemink O, eds. Colonial subjects: Essays on the practical history of anthropology. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press; 2000.

- [Google Scholar]