Translate this page into:

Why we don’t get doctors for rural medical service in India?

Corresponding Author:

Kanjaksha Ghosh

Surat Raktadan Kendra and Research Centre, 1st Floor Khatodara Urban Health Centre, Udhna Magdalla Road, Surat 395002, Gujarat

India

kaniakshaghosh@hotmail.com

| How to cite this article: Ghosh K. Why we don’t get doctors for rural medical service in India?. Natl Med J India 2018;31:44-46 |

Introduction

India has developed and modified a large healthcare infrastructure for rural medical service since Independence. Presently, the structure envisages subsidiary health centres (SHCs for 3000–5000 people) without doctors but manned by nurses and paramedical staffs, primary health centres (PHCs for 30 000 people) with one doctor and paramedical staffs, and community health centres (CHCs for 100 000 people) with four specialists (physician, surgeon, gynaecologist and paediatrician) along with paramedical staff and operating facilities. From CHCs, patients can be referred to better-equipped taluka (subdivision) or district hospitals, which are supposed to have all the facilities required for managing 90% of ailments.

I grew up in a remote village, which in 1962 came under an SHC manned by a doctor (rules in West Bengal were different at that time). He used to make a monthly visit to my village along with a public health nurse. Now when I go to my village, I find the health centre has all but vanished.

For the past 70 years, we were told that doctors do not want to go to villages and various governments tried several methods to encourage doctors to serve in rural areas but undoubtedly failed. I examine whether this premise is valid in the light of available data.

Government Health Service in India: Some Facts

Since Independence, when 725 PHCs (1951 data) were available till the Twelfth Five-Year Plan (latest available data), over 24 000 PHCs have been built.[1] The CHC facility was envisaged during the Sixth Five-Year Plan in 1984 when 761 such facilities were available and this number has increased to 4833 during the Twelfth Five-Year Plan.[1] While the number of PHCs increased almost 35 times since 1951, the number of CHCs increased nearly 7 times in the past 30 years.

However, during the same duration, the population has increased from 36 million to 1.27 billion (3.5 times). Hence in real terms if we consider that a PHC is for 20–30 000 people and if there are 24 000 PHCs then we need at least another 24 000 PHCs. Similarly, if a CHC is needed for 70–100 000 population then we need at least another 12 000 CHCs, three times more than the present number.

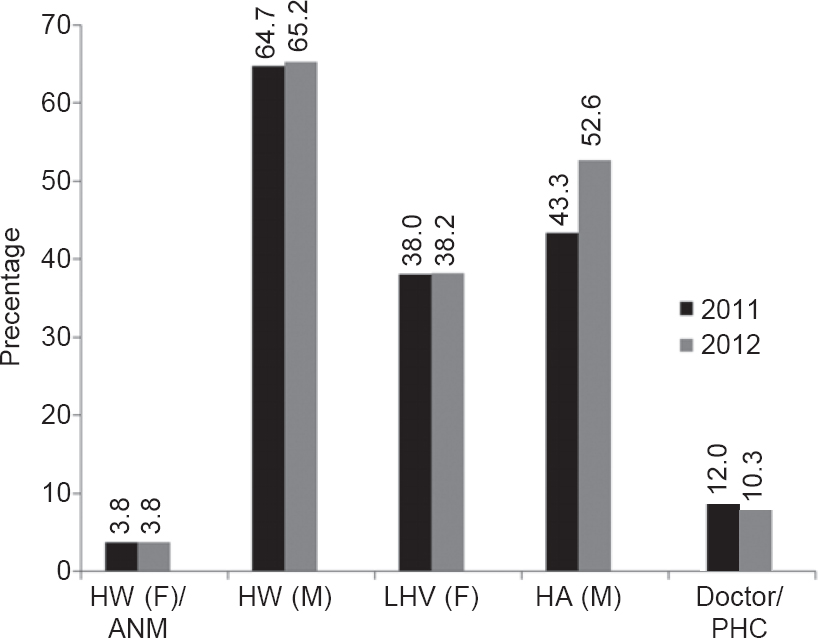

The data from the National Rural Health Mission[2] show that, at present, <10% of PHCs do not have a medical officer [Figure - 1]. This is much better than what governments would like us to believe. Thus, of the 24 000 PHCs, <250 do not have trained medical officers. However, the distribution of medical officers is not uniform across regions. A study from Odisha showed 30% deficiency of doctors[3] in rural settings.

|

| Figure 1: Shortfall against requirement of various staffs in percentage at the primary health centre (PHC) level in 2012 (taken from reference 2). HW (F)/ANM health worker female/auxiliary nurse cum midwife HW (M) health worker male LHV (F) lady health visitor HA (M) health assistant male |

Data from the National Rural Health Mission[2] also suggest a 30% deficit in medical professionals in CHCs where specialist doctors (post-MD/MS) are usually employed.

Measures Taken by Governments to Encourage Doctors to Serve in Rural Areas

Various state governments tried different plans to encourage doctors to serve in rural areas using several strategies, e.g.

- district quota for MBBS entrance

- specialized cadre (barefoot doctor training) for rural service

- three months’ community medicine internship in rural areas

- bond of different denominations beginning from ₹100 000 to now a proposed ₹1 crore (10 million) for serving in rural areas

- government sponsorship quota for postgraduate diploma and degree course selection

- selection of candidates under rural service schemes

- doubling the seats in government medical colleges to increase the supply of medically trained doctors

- starting a DNB programme as an alternative to the MD/MS programme

- DNB training at district hospitals

- increase the number of medical colleges to have one in each district

- use graduates of the AYUSH systems of medicine to man rural healthcare.

Before I discuss all these points it will be germane to discuss some of the means used to ‘create’ doctors in India and then discuss why doctors are not going to villages.

Training in Medical Colleges

Getting admission in a government medical college in India is an uphill task. The role model of most ‘potential’ doctors is an extremely busy urban practitioner who lives a life of affluence. Hence, none of the actions such as district and rural quotas for admission, or 3 months’ rural internship without any other supporting action is likely to work.

Curriculum

The curriculum for medical undergraduation and postgraduation has little Indian context except in community medicine to which students usually pay scant attention. Research done in India on our health challenges, many of which are in rural areas such as infectious diseases, chronic undernutrition, chronic parasitism, iron and other trace element deficiency, fluorosis, problems of personal hygiene and water, milk, food sanitation, haemo-globinopathies, alcoholism, etc. do not get enough mention in the study material for our undergraduate and postgraduate students. If a doctor is not trained to tackle diseases that afflict a large part of the rural community, she is unlikely to find any interest in managing these diseases.[4]

Meagre exposure and relative lack of teaching of clinical skills

In extremely busy hospitals, our students get little exposure to clinical skills and are largely dependent on laboratory and imaging information, which are not available in rural health centres. While there is no harm in using such facilities where available, in a rural setting our present graduates and postgraduates feel helpless and threatened. The training during internship used to prepare the ‘doctor’ to face the real world. However, it has become a casualty to the postgraduate entrance examination and the 3-month community medicine exposure in the rural setting is in jeopardy.

Forcing doctors to serve in rural areas

State governments have tried to force doctors to serve in rural areas by force—executing bonds of various amounts but are not ready to give an ‘appropriate’ salary to them. They often get a paltry sum of ₹8000-12 000 per month. Moreover, due to various reasons these bonds are not enforceable.

Most state governments have no clear policy on what is to be done with doctors who have furnished a bond for rural service. It is not clear whether these doctors will be inducted into a regular service cadre, or whether the bond period will be counted as years of experience in service, etc.

Facilities for patients, caregivers and doctors

A single doctor in a PHC has few medicines (20 tablets, 10 injections and 5 syrups[5]), hardly any investigative tools and no one with whom she can discuss a problem case. A doctor in a PHC is therefore likely to feel constrained by the facilities. The government is now throwing them into the bottomless pit of rural health service. These doctors are young, may be married and have small children. With no social interaction, no schools for their children and no healthcare facilities for themselves or their families, it is not surprising that they are not inclined to work in such an environment. The same would be true for AYUSH graduates. Many PHCs in India are located in remote places far from villages they serve. The villagers are often separated from the PHCs by thousands of acres of agricultural lands. This physical isolation also discourages many young doctors from joining PHCs in rural India. The shortfall of paramedical staff in PHCs is more than that of doctors (38%–65%; [Figure - 1], but this is rarely discussed.

Lessons from states which have solved the problem

It seems that there is no shortage of doctors, at least in some regions. There is a waiting list of doctors to serve in rural areas under the Government of Tamil Nadu. Bruno Mascarenhas[5] analysed several reasons for this. Most of these are around working conditions and environment and include posting husband and wife as close or together if possible, easy transfer if so desired, recognition for hard work, regular salary structure, some positive action for a seat in postgraduate degree or diploma course, freedom to work with other government/public/non-governmental organizations to improve some facets of the working of the PHC, freedom to prescribe from a large medicine base. A similar situation exists in Kerala.

States affected by insurgency such as Chhattisgarh claim to have reduced the vacancy of doctors in troubled areas from 95% to 45% by bringing them under a separate umbrella of Chhattisgarh Rural Medical Corps (CRMC). This segregation from other health service has allowed the government to provide these doctors with financial incentives, residential accommodation, life insurance and extra marks for postgraduate admissions.[6]

Discussion

It is clear that statistics do not show that doctors do not want to go to rural areas at PHCs. All over India the shortfall of doctors in PHCs of rural areas against the projected requirement is only 10%, which may not be very different from that of shortfall in government hospitals in urban areas of India. However, statistics can hide the inhomogeneity in distribution of doctors in rural areas in India. In backward, poorly developed and insurgency-prone areas the shortage of medical manpower could be more acute but this is not restricted only to doctors.

Statistics also show that the shortfall in PHCs is more among paramedical staff than doctors. This is unlikely to be solved by opening schools for barefoot/rural doctors.[7],[8] Neither forcing doctors to go to rural areas will work. Force and legislation can bring doctors to villages but if they are not involved and interested in their work then the results are not likely to be optimum and healthcare delivery will suffer.

Bruno Mascarenhas[5] has given many reasons why doctors in Tamil Nadu are more receptive to working in rural areas. Most of these reasons revolve around incentives of different kinds[9] but more important than the incentives is probably development of a friendly and sociable environment where the doctor’s family can gainfully spend their time.

Motivational factors such as interesting work, respect and recognition, comfortable working conditions, competent, considerate supervisor/mentor, etc.[10] and promotional avenues are also important.

There has been some discussion on the necessity of revamping the healthcare infrastructure.[11] This drastic change may not be required. The Indian healthcare system may not need a revolution, only evolution through gentle modification.

The requirements and ambitions of a medical graduate and postgraduate are different and hence there is a larger shortfall of specialists in CWCs than MBBS doctors in PHCs. Many doctors, once they have established their own practice, resent frequent transfers. Moreover, the government health administrative infrastructure is slow in disbursing incentives when these are due[6] and corruption at various levels of this system puts off young doctors (e.g. blocked transfers, delayed incentives, duty and travel allowance payments delayed). Specialists may need a separate kind of handling if their services are to be harnessed optimally.

At a PHC there is only one medical doctor serving a population of 30 000. This is grossly inadequate. Provision for more doctors with a better population–doctor ratio will end doctor’s working alone. Harnessing telemedicine-based training and distant learning programmes[12] will also improve medical interaction in rural areas.

Medical colleges need to modify their curriculum, incorporate challenges facing Indian rural healthcare, inform our graduates of the research done by Indian scientists, especially those relevant to our settings, which have been accepted and applied globally (e.g. oral rehydration therapy for diarrhoea, DOTS for TB, iodine deficiency, etc.).

The Diplomate of the National Board (DNB) programme should be made as was envisaged in the beginning and all district hospitals could be recognized for the same in broad specialties. Finally, and most important, living conditions in many of our villages need to be improved.

Developing manpower covering every aspect of healthcare, i.e. medical, paramedical and nursing should be aggressively persued[13] so that we can reach the norms prescribed by WHO within a decade and relevant changes made so that such trained manpower are retained by the system.[14]

Acknowledgement

My grandfather Dr Krishnaprasanna Ghosh treated his innumerable patients in a village for 62 years without caring for financial rewards.

Conflicts of interest. None

| 1. | Mavalankar DV, Ramani KV, Patel A, Sankar P. Building the infrastructure to reach and care for the poor: Trends, obstacles and strategies to overcome them. Ahmedabad:Center for Management of Health Services, Indian Institute of Management. Available at www.iimahd.ernet.in/publications/data/2005-03-01mavalankar.pdf (accessed on 12 Jun 2017). [Google Scholar] |

| 2. | Rural Health Statistics in India 2012. New Dellhi:Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India; 2012. Available at mohfw.nic.in/WriteReadData/ l892s/492794502RHS%202012.pdf (accessed on 12 Jun 2017). [Google Scholar] |

| 3. | Nallala S, Swain S, Das S, Kasam SK, Pati S. Why medical students do not like to join rural health service? An exploratory study in India. J Fam Community Med 2015;22:111-17. [Google Scholar] |

| 4. | Taneja DK. Rural doctors course: Need and challenges. Indian J Pub Health 2010;54:1-2. [Google Scholar] |

| 5. | Bruno Mascarenhas JM. Overcoming shortage of doctors in rural areas: Lessons from Tamil Nadu. Natl Med J India 2012;25:109-11. [Google Scholar] |

| 6. | Lisam S, Nandi S, Kanungo K, Verma P, Mishra JP, Mairebam DS. Strategies for attraction and retention of health workers in remote and difficult to access areas of Chhattisgarh, India: Do they work? Indian J Public Health 2015;59:189-95. [Google Scholar] |

| 7. | Ghosh K. Bachelor of rural health care: Cutting the root and watering the stem! Natl Med J India 2010;23:250. [Google Scholar] |

| 8. | Ananthakrishnan N. Proposed bachelor’s degree in rural healthcare: An unmixed blessing for the rural population or for the graduate or neither? Natl Med J India 2010;23:250-1. [Google Scholar] |

| 9. | Rao KD, Ryan M, Shroff Z, Vujicic M, Ramani S, Berman P. Rural clinician scarcity and job preferences for doctors and nurses in India: A discreet choice experiment. Plos One 2013;8:e82984.1-9. [Google Scholar] |

| 10. | Purohit B, Bandyopadhyay T. Beyond job security and money: Driving factors of motivation for government doctors in India. Hum Resour Health 2014; 12:12. [Google Scholar] |

| 11. | Patel V, Parikh R, Nandraj S, Balsubramaniam P, Narayan K, Paul VK, et al. Assuring health coverage for all India. Lancet 2015;386:2422-35. [Google Scholar] |

| 12. | Vyas R, Zacharah A, Swamidasan I, Doris P, Harris I. Blended distance education programme for junior doctors working in rural hospitals in India. Rural Remote Health 2014;14:2420-6. [Google Scholar] |

| 13. | Rao KD, Bhatnagar A, Berman P. So many, yet few: Human resources for health in India. Human Resour Health 2012;10:1-9. [Google Scholar] |

| 14. | Sundararaman T, Gupta G. Indian approaches to retaining skilled health workers in rural areas. Bull World Health Organ 2011;89:73-7. [Google Scholar] |

Fulltext Views

5,501

PDF downloads

11,979