Translate this page into:

Yoga nidra practice shows improvement in sleep in patients with chronic insomnia: A randomized controlled trial

Correspondence to HRUDA NANDA MALLICK; drhmallick@yahoo.com

How to cite this article: DATTA K, TRIPATHI M, VERMA M, MASIWAL D, MALLICK HN. Yoga nidra practice shows improvement in sleep in patients with chronic insomnia: A randomized controlled trial. Natl Med J India 34:2021;143-50.

Abstract

Background

Yoga nidra is practised by sages for sleep. The practice is simple to use and has been clearly laid out, but its role in the treatment of chronic insomnia has not been well studied.

Methods

In this randomized parallel-design study conducted during 2012–16, we enrolled 41 patients with chronic insomnia to receive conventional intervention of cognitive behavioural therapy for insomnia (n=20) or yoga nidra (n=21). Outcome measures were both subjective using a sleep diary and objective using polysomnography (PSG). Salivary cortisol levels were also measured. PSG was done before the intervention in all patients and repeated only in those who volunteered for the same.

Results

Both interventions showed an improvement in subjective total sleep time (TST), sleep efficiency, wake after sleep onset, reduction in total wake duration and enhancement in subjective sleep quality. Objectively, both the interventions improved TST and total wake duration and increased N1% of TST. Yoga nidra showed marked improvement in N2% and N3% in TST. Salivary cortisol reduced statistically significantly after yoga nidra (p=0.041).

Conclusion

Improvement of N3 sleep, total wake duration and subjective sleep quality occurred following yoga nidra practice. Yoga nidra practice can be used for treatment of chronic insomnia after supervised practice sessions.

INTRODUCTION

Cognitive behavioural therapy for insomnia (CBTI) remains an effective non-pharmacological treatment in patients with chronic insomnia. Although CBTI is considered beneficial, it remains underutilized,1 primarily because of the cost and increased time of treatment. Most peripheral centres cannot offer CBTI because of lack of trained workforce and financial constraints.

Many therapies have been tried for insomnia such as acupuncture, Kundalini yoga,2 Tai Chi Chi,3 mindfulness meditation4 and Chinese herbal medicines. Yoga nidra is an ancient technique that sages used to sleep. The method of doing yoga nidra was taught from guru (teacher) to shishya (disciple) and was not documented until the 1960s when a teacher from the Bihar School of Yoga, Munger, Bihar, India, enumerated the method to practice yoga nidra for novices. He described yoga nidra as a ‘systematic method of inducing complete physical, mental and emotional relaxation achieved by turning inwards, away from outer experiences’.5 He wrote instructions in a simple form and the practice can be done following instructions from his book. Copyrighted audio CDs are also available. The practice is taught to novices during daytime when they are most alert to avoid sleep during the practice. A model to use yoga nidra was developed using feedback from the school by one of the authors (KD) and was tested on patients with insomnia who volunteered.6

Yoga nidra unlike meditation is an aware state and is done in the supine position.5 The practice is easy and does not require any exercises or difficult postures, which makes it acceptable to patients with disabilities. It has been tried as a therapeutic option for some diseases,7,8 but its role in sleep disorders is lacking. We therefore assessed yoga nidra as a therapeutic option for patients with chronic insomnia as it is safe and easy to administer.

METHODS

The study was done at a tertiary referral institute in India and was approved by the institutional ethics committee (IESC/T-394/02.11.2012). The trial was registered with the Clinical Trials Registry India (CTRI/2013/05/003682). The trial design was parallel with CBTI (recommended intervention) and yoga nidra (experimental intervention) being the two limbs. No changes were done to the methods after trial commencement. The study was conducted from 2012 to 2016.

Patients were informed about the study by placing advertisements in the institution’s campus, outpatient department (OPD) and in the city including metro stations and bus stands, and they were asked to report to the Sleep OPD at the institute. Patients diagnosed to have chronic insomnia who volunteered to be a part of the study were assessed for eligibility and randomized using the sealed opaque envelope method. All the patients were explained about the nature of the study, and informed consent was obtained. After the baseline assessment, randomization was done and the patients were referred for the intervention. The CBTI intervention was done in the sleep OPD by psychologists trained in CBTI, and the yoga nidra intervention was done by one of the investigators (KD) also in the Sleep OPD. In both groups, no drugs were stopped or changed during the study and they continued the prescribed medications throughout the intervention.

Inclusion criteria

Patients with chronic insomnia who volunteered for the study were included. They were given the right to withdraw any time during the study. Patients in the age group of 25–60 years following normal sleep–wake schedule were included in the study. Normal sleep–wake schedule as reported by sleep history given by the patient was assessed by self-administered questionnaires and confirmed from the baseline sleep diary.

Exclusion criteria

Patients who were likely to plan an intercontinental flight or were not able to follow the usual sleep–wake schedule during the study period were excluded.

Outcome measures

Outcome was measured using both subjective and objective parameters.

The sleep diary parameters included sleep diary time in bed (TIB), sleep onset latency (SOL), wake after sleep onset (WASO), total sleep time (TST), sleep efficiency (SE)=(TST/TIB)×100 and total wake duration (TWD). A sleep diary analysis was done.6

Self-administered questionnaires

The following were used: Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI),9 Insomnia Severity Index (ISI),10 Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS),11 Epworth Sleepiness Scale,12 (ESS© MW JOHNS 1990–1997; used under license) and Pre-Sleep Arousal Scale (PSAS).13

Overnight digital polysomnography

This was done in the sleep laboratory using the standard American Association of Sleep Medicine criteria,14 on SOMNOmedics© polysomnography (PSG) system, Germany. The parameters studied were TIB, TST, WASO, SOL, rapid eye movement (REM) SOL and SE. Various stages of REM and nonREM sleep (N1, N2 and N3) were scored and calculated as percentage of TST and TIB.

Salivary cortisol estimation

DiaMetra© salivary kit using the ELISA method was used. The sample was collected with adequate precautions of time of day, i.e. collection only between 11 a.m. and 3 p.m. The participants were instructed to keep restriction of food, exercise and smoking of 1 hour before salivary sample collection as required for estimation of cortisol. The salivary sample was taken during baseline assessment and on completion of intervention. Only if the salivary sample was clear, i.e. no contamination with food, lipstick or blood (bleeding gums), it was put for analysis.

Outline of CBTI for insomnia

The CBTI intervention, done by the therapist, consisted of six sessions including the first baseline and assessment sessions, each session was for 45–60 minutes. We used multicomponent CBTI15 in our study as it has been found to have better results.16

Yoga nidra intervention

Yoga nidra practice was done using the copyrighted audio CD from the Bihar School of Yoga after prior permission. The supervised sessions were done in a laboratory, and the yoga nidra intervention model was standardized for yoga nidra practice as reported by Datta et al.,6 and guidelines developed for the observer to standardize the practice (Appendix A).

The CBTI therapist and KD used a sleep diary to monitor the intervention period. No analysis of sleep diary was done during the intervention period. The patients were monitored at least once a month and were instructed to report any time during the intervention in case of feeling unwell. Table I shows a comparison of the two interventions.

| CBTI intervention | Yoga nidra intervention |

|---|---|

| Similarities | |

| Non-pharmacological | |

| Requires time for sessions Self-motivation important to continue, as improvement is seen slowly | |

| Cost involved for sessions, transport to site, leave on the day of session, etc. | Cost involved for transport to site, leave on the day of session, CD, etc. |

| Differences | |

| Weekly/biweekly session at regular intervals for several weeks and then practices at home on his/her own | Initial five supervised sessions in the first week and then practice at home on his/her own |

| Patient dependant on the CBTI giver at least till the time sessions are over | Patient dependant only for the first week, then practices at home on his/her own |

| Methodology is a multicomponent approach using stimulus therapy, relaxation, cognitive and behavioural therapy, and sleep restriction and sleep hygiene | Methodology is using the yoga nidra model, which is a complementary and alternative medicine approach |

The patients of both the groups were reminded repeatedly of their appointments from the offices of two of the authors, and adherence was enhanced by giving an appointment of choice on the day of intervention/assessment/follow-up. The objective was to study the role of the yoga nidra intervention in the treatment of patients with chronic insomnia. As a pilot project, the study was planned with 30 patients in each arm, i.e. total 60 patients.

Randomization and blinding

Randomization was done using random number charts and concealment by the opaque envelop method. The assessor was blinded to the identity of the patient and also the type of intervention. The questionnaires were filled by the patient in the office at regular intervals. A unique identification number (ID) of each patient given at the time of randomization was marked on the questionnaires with date. The data were entered by the support staff who were blinded to the type of intervention for each ID. The salivary samples were collected centrally, marked with ID and date and sent for estimation. The laboratory technician was blinded to the type of intervention. The PSG files were coded, without ID and given to KD in batches of 8–10 files.

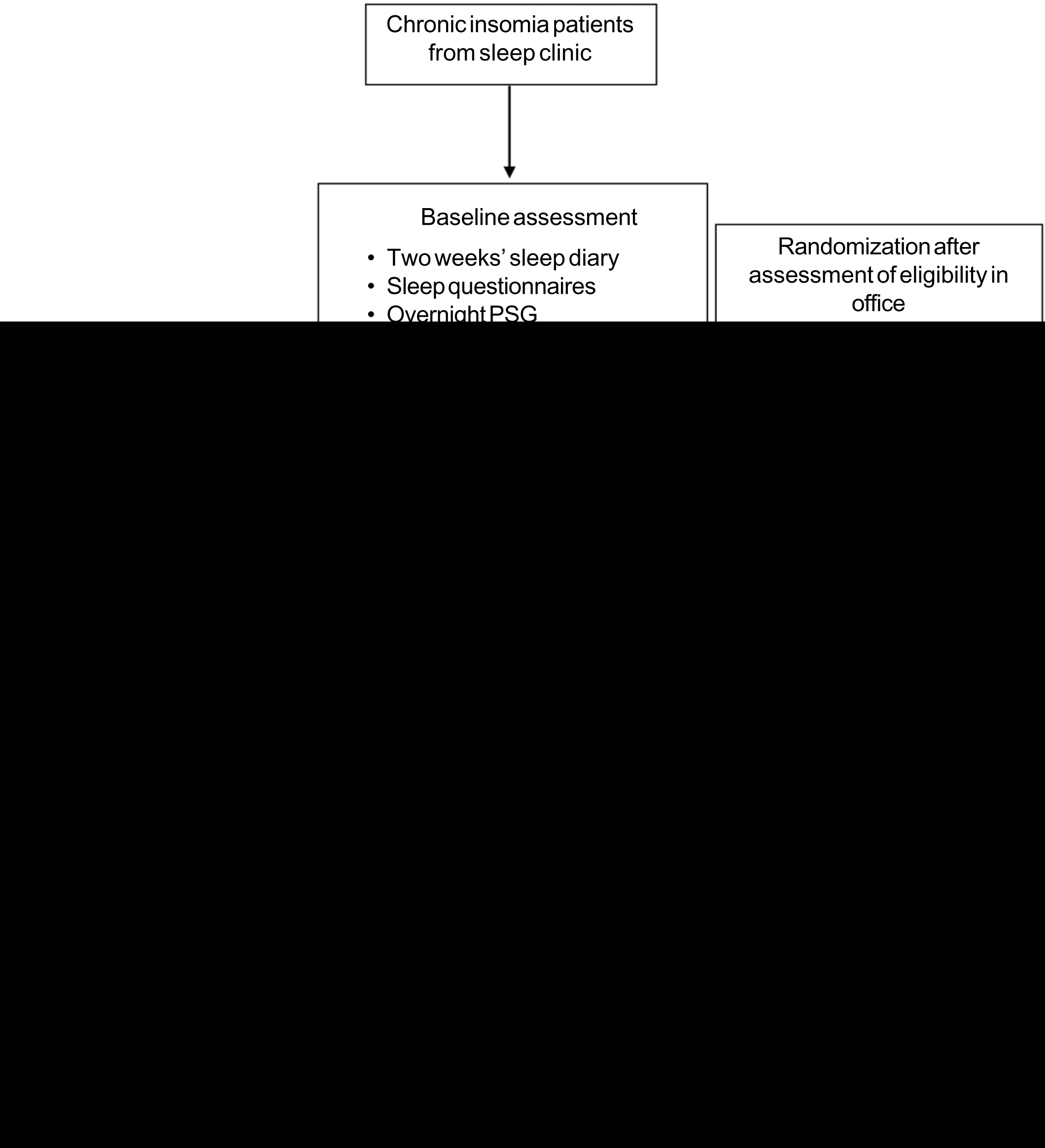

The PSG files were all scored by KD who was blinded to the patient identity and also the timing of PSG, whether baseline or post-intervention because of coding. The PSG files were decoded after scoring by another researcher and the data were entered by the staff. The sleep diary was collected from the patients at the end of the intervention and ID was marked, with personal particulars, if any, removed. These data were also filled by the staff who were blinded about the type of intervention. Figure 1 shows the study design.

- The study design

Baseline assessment

After obtaining informed consent from the patient, and assessing for eligibility, baseline assessment was done. Apart from the 2 weeks’ sleep diary, the patients completed self-administered questionnaires. The Morningness–Eveningness scale17 was used to screen the participants. Only those with morning preference were included in the study. Baseline overnight PSG was done.

Yoga nidra-supervised sessions6

Assessment after 2 weeks from the start of the intervention: PSQI, ESS, ISI and PSAS were completed. The patients were instructed to continue filling the sleep diary.

Assessment at the end of the intervention: PSQI, ESS, ISI and PSAS were completed by the patient. Saliva for cortisol estimation was collected. PSG was repeated if the patients volunteered.

The sleep diary was filled by the patients throughout the study and submitted for analysis only after the entire study was completed. The sleep diary was not analysed in between nor was used to monitor the patient.

The data thus obtained were analysed using Cohen’s d effect size (ES) to compare between the two interventions. ES was calculated using Cohen’s d formula where 0.2–0.5 is mild effect, 0.5–0.8 is moderate and more than 0.8 is large effect. The pre- and post-intervention was studied using analysis of variance (ANOVA) and t-test. A value of p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

The intervention was implemented in both the groups as mentioned above. The recruitment announcement was done from February 2012, and the randomization after baseline assessment was started from May 2012. The trial was done with no changes in the methods after registration of the trial. The trial was continuously under the Data Safety Monitoring Board. Figure 2 shows the CONSORT 2010 flow diagram. There was no significant difference in baseline parameters of the two intervention groups (Table II).

- The Consort diagram

| Characteristic | Both groups | CBTI group (n=20) | Yoga nidra group (n=21) | p value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 43.29 (11.53) | 41.65 (12.33) | 44.86 (10.80) | 0.38 |

| SDSQ (out of 10) | 4.77 (2.17) | 4.71 (2.08) | 4.81 (2.14) | 0.64 |

| TIB (minutes) | 425.95 (61.52) | 424.89 (64.09) | 426.90 (60.68) | 0.53 |

| TST (minutes) | 312.08 (83.9) | 297.36 (93.88) | 301.24 (81.86) | 0.58 |

| SOL (minutes) | 25.85 (39.23) | 20.55 (21.45) | 29.10 (50.30) | 0.84 |

| SE (%) | 73.95 (13.35) | 72.91 (21.48) | 72.10 (13.16) | 0.25 |

| WASO (minutes) | 81.63 (51.98) | 85.45 (67.41) | 88.24 (55.93) | 0.47 |

All values are mean (SD) *t-test SDSQ sleep diary sleep quality TIB time in bed TST total sleep time SOL sleep onset latency SE sleep efficiency WASO wake after sleep onset

Sleep diary data of patients with insomnia

All patients filled the baseline sleep diary, but only 17 patients from the yoga nidra group and 13 of the CBTI group submitted their completed diaries and their data were analysed (Table III).

| Group | Yoga nidra group | CBTI | group | Comparison of interventions | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | p value* | Mean (SD) | p value* | ES (Cohen’s d)† Yoga nidra/CBTI | |

| Time in bed | |||||

| Baseline | 448.79 (87.13) | NS (B-M) | 455.79 (91.51) | NS | -0.049/-0.14 |

| Mid-intervention | 458.05 (74.53) | NS (M-P) | 471.53 (91.74) | NS | 0.07/0.30 |

| Post-intervention | 452.63 (70.21) | NS (B-P) | 449.67 (91.68) | NS | 0.02/0.16 |

| Total sleep time | |||||

| Baseline | 324.73 (105.00) | p<0.0005 (B-M) | 293.75 (125.88) | p=0.004 | -0.39/-0.27 |

| Mid-intervention | 368.58 (104.36) | NS (M-P) | 334.08 (118.25) | NS | -0.09/0.007 |

| Post-intervention | 377.80 (93.08 | p<0.0005 (B-P) | 333.85 (125.12) | p=0.005 | -0.50/-0.26 |

| Sleep efficiency | |||||

| Baseline | 74.13 (22.23) | p=0.001 (B-M) | 64.55 (24.40) | p=0.011 | -0.34/-0.24 |

| Mid-intervention | 81.47 (21.02) | NS (M-P) | 71.50 (22.64) | NS | -0.16/-0.17 |

| Post-intervention | 84.76 (18.96) | p<0.0005 (B-P) | 74.11 (24.22) | p=0.0004 | -0.52/-0.40 |

| Sleep onset latency | |||||

| Baseline | 92.73 (98.77) | p=0.013 (B-M) | 73.82 (78.19) | NS | 0.30/-0.06 |

| Mid-intervention | 68.33 (98.77) | NS (M-P) | 69.19 (82.63) | NS | 0.14/-0.05 |

| Post-intervention | 55.76 (83.81) | p<0.0005 (B-P) | 75.23 (89.18) | NS | 0.45/-0.11 |

| Wake after sleep onset | |||||

| Baseline | 36.94 (59.30) | p=0.002 (B-M) | 90.34 (93.31) | p=0.019 | 0.25/0.28 |

| Mid-intervention | 21.75 (41.83) | NS (M-P) | 68.71 (75.93) | p=0.010 | 0.07/0.46 |

| Post-intervention | 18.99 (36.77) | p<0.0005 (B-P) | 44.27 (58.12) | p<0.0005 | 0.32/0.72 |

| Total wake duration | |||||

| Baseline | 122.15 (109.48) | p=0.002 (B-M) | 159.82 (119.56) | NS | 0.32/0.13 |

| Mid-intervention | 88.47 (106.18) | NS (M-P) | 135.95 (119.04) | NS | 0.13/0.19 |

| Post-intervention | 75.35 (100.59) | p<0.0005 (B-P) | 122.31 (113.65) | p=0.007 | 0.46/0.32 |

| Sleep quality | |||||

| Baseline | 4.81 (2.14) | p<0.0005 (B-M) | 4.71 (2.21) | p<0.0005 | -0.33/-0.38 |

| Mid-intervention | 5.69 (2.20) | NS (M-P) | 5.66 (2.11) | NS | -0.17/-0.04 |

| Post-intervention | 6.04 (1.95) | p<0.0005 (B-P) | 5.89 (2.56) | p<0.0005 | -0.53/-0.39 |

NS not significant *p<0.05 was set as significant †ES (Cohen’s d values) of various sleep diary parameters in both groups comparing both interventions mid-intervention was 4 weeks after the start of the study for both groups. For both groups, post-intervention was 8 weeks after start of the study; for example, for the yoga nidra group, it included baseline, 4 weeks of yoga nidra and last 2 weeks of post-intervention sleep diary and for the CBTI group, it was 6 sessions including baseline and assessment sessions. B–M baseline to mid-intervention B–P baseline to post-intervention M–P mid-intervention to post-intervention ES was calculated using Cohen’s d formula where 0.2–0.5 is mild effect, 0.5–0.8 is moderate and more than 0.8 is large effect. p values using ANOVA and post hoc Tukey’s test

Overnight polysomnography results

Baseline PSG was done in all patients for both the groups. Eleven from the CBTI group and 15 from the yoga nidra group volunteered for repeat PSG (Table IV).

| Pair | Difference between baseline and post-intervention polysomnography parameters | CBTI group (n=11) | Yoga nidra group (n=15) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p value | Cohen’s d* | p value | Cohen’s d* | ||

| i | Time in bed | 0.625 | 0.241571 | 0.733 | 0.024376 |

| 2 | Total sleep time | 0.533 | 0.282868 | 0.099 | 0.691999 |

| 3 | Sleep onset latency | 0.327 | 0.270116 | 0.014† | 0.258938 |

| 4 | Sleep efficiency | 0.824 | 0.280219 | 0.002† | 1.157467 |

| 5 | Wake after sleep onset | 0.859 | 0.434623 | 0.074 | 0.525532 |

| 6 | Wake after sleep onset/total sleep time | 0.102 | 1.068249 | 0.564 | 0.196721 |

| 7 | Rapid eye movement (REM) sleep onset latency | 0.050 | 0.543862 | 0.910 | 0.205993 |

| 8 | Wake duration | 0.657 | 0.275396 | 0.003† | 1.084154 |

| 9 | Wake % time in bed | 0.859 | 0.29589 | 0.008† | 1.144934 |

| 10 | N1 duration | 0.824 | 0.104786 | 0.109 | 0.458476 |

| 11 | N1% time in bed | 0.798 | 0.146822 | 0.068 | 0.514608 |

| 12 | N1% total sleep time | 0.965 | 0.371475 | 0.488 | 0.216684 |

| 13 | N2 duration | 0.894 | 0.142908 | 0.478 | 0.290858 |

| 14 | N2% time in bed | 0.789 | 0.147643 | 0.842 | 0.122324 |

| 15 | N2% total sleep time | 0.824 | 0.176919 | 0.041† | 0.902482 |

| 16 | N3 duration | 0.799 | 0.073974 | 0.078 | 0.047991 |

| 17 | N3% time in bed | 0.533 | 0.012373 | 0.005† | 0.862326 |

| 18 | N3% total sleep time | 0.505 | 0.067635 | 0.060 | 0.538498 |

| 19 | REM duration | 0.041† | 0.592354 | 0.182 | 0.487671 |

| 20 | REM % time in bed | 0.026† | 0.641518 | 0.151 | 0.485909 |

| 21 | REM % total sleep time | 0.082 | 0.539259 | 0.509 | 0.201119 |

N1, N2 and N3 NREM sleep *Effect size was calculated using Cohen’s d formula where 0.2–0.5 is mild effect, 0.5–0.8 is moderate and more than 0.8 is large effect. Comparing both interventions for both groups, post-intervention was 8 weeks after start of the study; for example, for the yoga nidra group, it included baseline, 4 weeks of yoga nidra and last 2 weeks of post-intervention sleep diary and for the CBTI group it was six sessions including baseline and assessment sessions †<0.05

Patient questionnaire analysis

The mean (SD) values of ISI, PSAS total score, PSAS somatic score, PSAS cognitive score, PSQI, ESS, D of DASS, A of DASS and S of DASS for both the groups are given in Table S1 (available at www.nmji.in), and the statistical results are summarized in Table V.

| Questionnaire | p value Yoga nidra/CBTI | Yoga nidra effect size* | CBTI effect size* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Insomnia Severity Index (ISI) | <0.0005/0.337 | 1.052677 | 0.734824 |

| Pre-sleep Arousal Scale (PSAS) total | <0.0005/0.026 | 1.298521 | 0.906316 |

| PSAS somatic score | 0.4780/0.305 | 0.384061 | 0.516963 |

| PSAS cognitive score | <0.0005/0.021 | 1.792338 | 0.927518 |

| PSQI (Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index) | <0.0005/0.028 | 2.066836 | 0.625147 |

| ESS (baseline-post-intervention) | 0.6560/0.828 | 0.505996 | 0.176888 |

| D of Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS) | 0.0700/0.607 | 0.750772 | 0.477042 |

| A of DASS | 0.1460/0.701 | 0.611588 | 0.235549 |

| S of DASS | <0.0005/0.142 | 1.355497 | 0.826828 |

Patient salivary cortisol estimation

The change in salivary cortisol in the yoga nidra group (baseline: 3.63 [1.99], post-intervention 2.16 [1.37] ng/ml) reduced significantly (p=0.04), whereas there was no effect (p=0.16) with CBTI (baseline 3.46 [1.16], post-intervention 2.61 [1.15] ng/ml).

Both the interventions showed an improvement in subjective TST (ES: CBTI; yoga nidra values=0.26; 0.50), SE (ES=0.40; 0.52), WASO (ES=0.72; 0.32), reducing total wake duration (ES=0.32; 0.46) and enhancing subjective sleep quality (ES=0.39; 0.53). Yoga nidra also showed improved SOL (ES=0.11; 045). Objectively, PSG showed similar results. Both the interventions improved TST (ES=0.28; 0.69) and reduced total wake duration (ES=0.29; 1.14).

Both the interventions increased N1% of TST (ES=0.37; 0.21). Yoga nidra also showed marked improvement in N2% of TST (ES=0.17; 0.90) and N3% of TST (ES=0.06; 0.53). Salivary cortisol reduced significantly after yoga nidra (p=0.04).

DISCUSSION

The CBTI and yoga nidra groups did not differ significantly in age, onset of illness or sleep parameters. We used multicomponent CBTI, which is the treatment of choice for chronic insomnia.18 Brief interventions did not show durable effects;19 hence, we had six sessions20 including assessment by the therapist. Although both interventions were offered at no extra cost, a relatively large number of patients refused non-pharmacological approach because it required repeated reporting.

In the CBTI group, we did not find any difference between subjective and objective sleep parameters, though such a difference has been noted in other studies,21 and small effect on subjective TST with large ES in subjective SOL, WASO and SE22 has also been reported. In the same group, we found a significant increase in REM SOL with significant improvement in ISI and in depression scale though this was not significant. REM sleep duration when analysed as a percentage of TST was not significantly reduced, implying that the sleep time percentages were not significantly different from pre-treatment values. The TWD, N1, N2 and N3 calculated from PSG did not show any significant change in our study with the CBTI intervention. Several factors may be responsible for this difference. In a randomized trial by Sivertsen et al.,23 on patients with insomnia above 55 years of age, CBTI showed improvement of SE and slow wave sleep (SWS) objectively by PSG. However, in our patients, the average age was much younger. They also had a baseline SE of >81% on PSG in all pre-treatment patients, whereas in our study, the average SE at baseline PSG was much lower (74%). We did not include a mood enhancement module which was used in a trial comparing CBTI with mindfulness meditation24 as it is not a standard CBTI regimen. Studies have reported improvement in objective criteria using PSG,22 which was also seen in our study. Studies have relied on sleep diary for effective monitoring during interventions; however, actigraphy could have been used.25

We found a subjective improvement in severity of insomnia and quality of sleep. Furthermore, significant reduction was seen in pre-sleep arousal. This was also found in night time arousal by Espie et al.26 where online CBT was administered. A significant improvement in the stress component was seen using the DASS scale. In a study done by Okajima et al. in 2011, a correlation of the Dysfunctional beliefs and attitudes about sleep (DBAS) score with Athens Insomnia score was found at baseline, but after intervention, improvement in the DBAS score did not necessarily show improvement in the insomnia score, implying different mediators for improvement in insomnia.21,27 We have not used improvement in the DBAS score in our study as an outcome measure for insomnia. Although initial improvement is seen with behavioural remedies,18 in our patients, the effect continued implying the effect of multi-component therapy.

In the yoga nidra group, moderate effect was seen on TST, SE and sleep quality using a sleep diary. Sleep diary analysis showed significant improvement in SE, sleep quality, wake duration and WASO. Questionnaire analysis showed significant improvement in sleep quality and in severity of insomnia. PSG showed an objective improvement in WASO. The improvement of SWS as a percentage of TST showed a moderate effect. As a percentage of TIB, SWS showed a moderate effect in PSG parameters. Yoga nidra has been found to be associated with a shift towards parasympathetic dominance,28 and high cardiac vagal control is related to better subjective and objective sleep quality.29 Yoga practice in the morning has been found to increase parasympathetic drive at night,30 causing sleep to be more restorative. In addition, the probable mechanisms which might affect sleep quality and subjectively feeling better may be linked to cognitive structuring effects of these practices, which make the mental processing of external inputs more relaxed.31 Objective improvement in SWS following the yoga nidra intervention may also explain the subjective sleep quality. Mindfulness meditation is known to target deficits in executive attention which characterize mood and anxiety32 and psychological symptoms.33 Therapies using a non-pharmacological approach are known and mindfulness meditation has been used as an approach to patients with insomnia.34,35 Reduction in sympathetic arousal and reduced emotional states are the probable reasons for improvement in patients with insomnia with mindfulness meditation.4,36,37

In our patients, yoga nidra produced increased TST unlike a study on meditators where a reduced sleep need due to meditation was proposed.38 This brings out the difference in meditators undergoing this practice from patients where it is being used as an intervention. It is also important that the intervention be given under supervision of a sleep practitioner because the changes seen in the patients need to be assessed and monitored especially when there is an increased association with anxiety, other somatic complaints such as headaches, nausea are likely to be more in patients with insomnia,39 with mind–body therapies including meditation.40 Our guidelines for observers (Appendix A; available at www.nmji.in) are to ensure a standardized intervention along with constant supervision by sleep practitioners.

This also highlights the differences between patients and healthy controls and hence the medical supervision of these patients is important unlike a healthy person undergoing a yoga nidra intervention.

We found that yoga nidra practice showed a significant improvement in TST, SE, SOL, WASO and SWS, whereas CBTI was found to affect WASO to a large extent with mild effects on TIB, TST and SE. This suggests that yoga nidra practice may be a better treatment for sleep initiation or sleep maintenance both compared to CBTI which showed good results on WASO, but probably will not be able to reduce sleep onset. CBTI is a recommended method, but lack of therapists trained in CBTI often poses problems in implementing this intervention. Yoga nidra practice is a good adjunct therapy for patients with insomnia provided the therapy is administered under the supervision of a sleep physician with monitoring of sleep and somatic symptoms during the intervention. It is simple to perform as after a few initial sessions, the individual can be left on his/her own to perform the practice with intermittent follow-up, if required.

This practice may also be of value where the patient is in remote areas and a therapist is difficult to reach for CBTI, but once trained in yoga nidra, the patient can perform the practice on his/her own. Future research of its use in military, isolated work areas of confinement and field may further highlight its role in such operational environments.

Conclusions

We found that yoga nidra practice and CBTI improved TST and total wake duration both subjectively and objectively. The yoga nidra intervention also improved SWS and SOL in patients. Yoga nidra practice in patients with chronic insomnia should be done using formulated guidelines during sessions to monitor the patients. Discussion after the session should be done to help the patient understand the practice. Yoga nidra practice is a good adjunct therapy to improve sleep in patients with insomnia.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We acknowledge support of the Bihar School of Yoga, Munger, Bihar, India, in providing valuable inputs, books, literature and blessings in designing and completing the study. We acknowledge the help provided by the sleep technicians in the sleep laboratory and the assistance of office staff in completing this study.

Conflicts of interest

None declared

References

- Clinical guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic insomnia in adults. J Clin Sleep Med. 2008;4:487-504.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treatment of chronic insomnia with yoga: A preliminary study with sleep-wake diaries. Appl Psychophysiol Biofeedback. 2004;29:269-78.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Improving sleep quality in older adults with moderate sleep complaints: A randomized controlled trial of Tai Chi Chih. Sleep. 2008;31:1001-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- A randomized controlled trial of mindfulness meditation for chronic insomnia. Sleep. 2014;37:1553-63.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoga nidra: An innovative approach for management of chronic insomnia-A case report. Sleep Sci Pract. 2017;1:7.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Therapeutic role of yoga in type 2 diabetes. Endocrinol Metab (Seoul). 2018;33:307-17.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoga nidra as a complementary treatment of anxiety and depressive symptoms in patients with menstrual disorder. Int J Yoga. 2012;5:52-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Pittsburgh sleep quality index: A new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989;28:193-213.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The insomnia severity index: Psychometric indicators to detect insomnia cases and evaluate treatment response. Sleep. 2011;34:601-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Psychometric properties of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) in clinical samples. Behav Res Ther. 1997;35:79-89.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- A new method for measuring daytime sleepiness: The Epworth sleepiness scale. Sleep. 1991;14:540-5.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The phenomenology of the pre-sleep state: The development of the pre-sleep arousal scale. Behav Res Ther. 1985;23:263-71.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The AASM Manual for the Scoring of Sleep and Associated Events: Rules, Terminology and Technical Specifications, Ver 2.0.3 Darien, Illinois: American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2014.

- [Google Scholar]

- Psychological and behavioral treatment of insomnia: Update of the recent evidence (1998-2004) Sleep. 2006;29:1398-414.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The epidemiology of morningness/eveningness: Influence of age, gender, ethnicity, and socioeconomic factors in adults (30-49 years) J Biol Rhythms. 2006;21:68-76.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comparative efficacy of behavior therapy, cognitive therapy, and cognitive behavior therapy for chronic insomnia: A randomized controlled trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2014;82:670-83.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of a brief treatment program of cognitive behavior therapy for insomnia in older adults. Sleep. 2014;37:117-26.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dose-response effects of cognitive-behavioral insomnia therapy: A randomized clinical trial. Sleep. 2007;30:203-12.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A meta-analysis on the treatment effectiveness of cognitive behavioral therapy for primary insomnia: CBT for insomnia: A meta-analysis. Sleep Biol Rhythms. 2011;9:24-34.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Cognitive behavioral treatment of insomnia. Chest J. 2013;143:554.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cognitive behavioral therapy vs zopiclone for treatment of chronic primary insomnia in older adults: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2006;295:2851-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cognitive behavioral therapy vs. Tai Chi for late life insomnia and inflammatory risk: A randomized controlled comparative efficacy trial. Sleep. 2014;37:1543-52.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The consensus sleep diary: Standardizing prospective sleep self-monitoring. Sleep. 2012;35:287-302.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of online cognitive behavioral therapy for chronic insomnia disorder delivered via an automated media-rich web application. Sleep. 2012;35:769-81.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mediators of cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia: A review of randomized controlled trials and secondary analysis studies. Clin Psychol Rev. 2012;32:664-75.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoga nidra relaxation increases heart rate variability and is unaffected by a prior bout of Hatha yoga. J Altern Complement Med N Y N. 2012;18:953-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- High cardiac vagal control is related to better subjective and objective sleep quality. Biol Psychol. 2015;106:79-85.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heart rate variability during sleep following the practice of cyclic meditation and supine rest. Appl Psychophysiol Biofeedback. 2010;35:135-40.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neurophysiological mechanisms of induction of meditation: A hypothetico-deductive approach. Indian J Physiol Pharmacol. 2002;46:136-58.

- [Google Scholar]

- The effect of focused attention and open monitoring meditation on attention network function in healthy volunteers. Psychiatry Res. 2013;210:1226-31.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The effects of “The Work” meditation (Byron Katie) on psychological symptoms and quality of life-A pilot clinical study. Explore (NY). 2015;11:24-31.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patients' acceptance of psychological and pharmacological therapies for insomnia. Sleep. 1992;15:302-5.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Combining mindfulness meditation with cognitive-behavior therapy for insomnia: A treatment-development study. Behav Ther. 2008;39:171-82.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mindfulness meditation and cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia: A naturalistic 12-month follow-up. Explore (NY). 2009;5:30-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The value of mindfulness meditation in the treatment of insomnia. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2015;21:547-52.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meditation acutely improves psychomotor vigilance, and may decrease sleep need. Behav Brain Funct. 2010;6:47.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Relaxation: Some limitations, side effects, and proposed solutions. Psychother Theory Res Pract Train. 1990;27:261-6.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Negative side effects of self-regulation training: Relaxation and the role of the professional in service delivery. Biofeedback Self Regul. 1991;16:191-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]