Translate this page into:

Can one be so wrong about NEET?

Corresponding Author:

Nilakantan Ananthakrishnan

Department of Surgery Mahatma Gandhi Medical College and Research Institute Puducherry

India

n.ananthk@gmail.com

| How to cite this article: Ananthakrishnan N. Can one be so wrong about NEET?. Natl Med J India 2018;31:254 |

In 2013, when the existence of the National Eligibility cum Entrance Test (NEET) was in question, I had written a letter to this Journal expressing apprehensions about the possibility of NEET not being implemented in the country.[1] I tried to clarify several misapprehensions about NEET and enumerated advantages of having such a common All-India Entrance cum Eligibility Test for medical admissions in India.[1]

Five years down the line, I realize that NEET is not the panacea it was claimed to be and may in fact be a solution which is worse than the problem it tries to address. Before NEET, admissions to medical colleges were based on state selections on universal regulatory criteria, viz. that to be eligible, candidates should have secured not less than 50% in the +2 examinations with not less than 50% individually in physics, chemistry and biology. The eligibility was relaxed for candidates belonging to the socially disadvantaged category. Where admissions were based on a state entrance examination, by and large the same criteria applied. It was considered that this system did not ensure uniform quality of the incoming candidates in view of vastly different syllabus and exit examinations of various school boards and hence a demand for an All-India Eligibility cum Entrance Examination to overcome variations in the standards of different state board examinations.

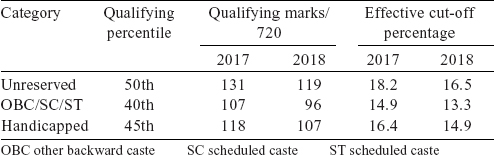

Has NEET served this purpose? The lack of clarity in the minds of the general public about the difference between percentile and percentage has contributed to the perception about NEET being superior. [Table - 1] shows an extract of the information published in the Times of India, dated 5 June 2018.[2]

It is seen that in 2017, candidates for the general category with as low marks as 18.2% got admission to MBBS and 16.5% for the same category are likely to get admission in 2018. Similar figures are seen for the reserved category for both years. A person who scored 119 in 2018 NEET could at best have got 33% of the answers correct.[2] Are we being short-charged by declaring NEET as being superior to the earlier system when a candidate had to score at least 50% in +2 in the relevant subjects to be eligible for medicine? Qualitatively, the batches admitted on the basis of NEET appear superior only by their ability to converse in English. Is the system unfair to those who do their schooling in a regional language? Is the curriculum of NEET so out of synch with the +2 syllabi of state and regional boards that students who scored high marks in +2 are able to secure only 17% and 18% marks in NEET? What is worse is that since there is no prescribed minimum (subject-wise) in NEET scores, candidates with as low as zero or negative marks, for example in chemistry, are eligible for a seat. Mere translation of the question paper into several languages does not ensure equivalence of syllabi.

A sorry state of affairs, indeed, in the opinion of those who are interested in quality in higher education. Have those responsible for introducing NEET thought it through and covered all bases particularly with equivalence of syllabi across the state boards? One does not know.

Another example of a less than perfect scheme introduced by the government with a laudable motive, viz. the National Institutional Ranking Framework (NIRF) of ranking universities have uniform criteria irrespective of the size of the university or the type of university or the service it provides. Many of them are blatantly unfair to health science universities where patient care is an important component, which gets no credit in the ranking process. Criteria such as campus placement are unknown for MBBS students and issues of intellectual property right are much less relevant than those for engineering or management institutions, particularly since patenting of processes beneficial to the health of human beings is prohibited by law. The highest mark scored among the universities this year in NIRF is 82.16% by the Indian Institute of Science (Bengaluru), whereas the highest score of a health science university is 52.73% by King George Medical University (Lucknow).

Thereby hangs a tale.

Conflicts of interest. None declared

| 1. | Ananthakrishnan N. Saying no to NEET is certainly not neat. Natl Med J India 2013;26:250-51. [Google Scholar] |

| 2. | Nagarajan R. As NEET cut-offs drop, 17% enough to join MBBS. Times of India, 5 June 2018. [Google Scholar] |

Fulltext Views

1,326

PDF downloads

284