Translate this page into:

Using generic drugs in India: Some thoughts

Corresponding Author:

Anil C Anand

Department of Hepatology and Gastroenterology, Indraprastha Apollo Hospitals, New Delhi

India

anilcanand@gmail.com

| How to cite this article: Anand AC. Using generic drugs in India: Some thoughts. Natl Med J India 2017;30:287-289 |

At a gastroenterology conferencae,[1] I moderated a panel discussion with four eminent hepatologists as co-panellists and many other senior members of our professional society in the audience. I had chosen the topic of generic drugs, as I wanted to share my newly gained knowledge about the use of branded drugs in the treatment of hepatitis C virus (HCV).

I was blissfully unaware of various practices during my service career as we had instructions to use names of generic drugs in our prescriptions. Our professional societies inexplicably avoid discussing such issues. After entering private practice a couple of years back, I learnt about certain wheeling/dealings from my friends in practice as well as those in pharmaceutical companies (PC).

The hall was jam-packed. Not because people were interested in this topic, but because the session immediately after the panel discussion was to feature a famous motivational speaker, Mr Shiv Khera. During the last 10 minutes, the organizers kept frantically signalling me to wind up my session quickly as Mr Khera had arrived in the hall earlier than expected.

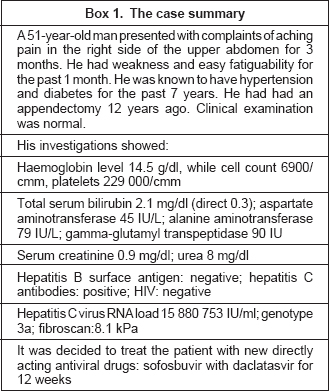

The panel discussion was about the index case described in [Box 1], where a decision was made to treat the patient with sofosbuvir and daclatasvir.

Sofosbuvir (trade name Sovaldi) is the same drug that had created ripples in the world when it was marketed in the USA by Gilead for US$ 1000 for one tablet. People shouted from rooftops, ‘$84,000 miracle cure (12 weeks’ course) costs less than $150 to make’,[2] forcing a Senate hearing.[3] The drug was found cost-effective by some people,[4] while others questioned if innovation and ethics can coexist?[5] The high cost remains an important factor everywhere and this led to a delay in its introduction in the National Health Service, UK[6] and near rejection by Australia.[7] Gilead then took steps to blunt the criticism about pricing of the drug. The company signed agreements with several large Indian drug-makers to sell cheaper versions of Sovaldi in 91 developing countries. These countries have an annual average per capita income of less than US$ 1900 and account for more than half of the global patients of HCV infection.

Our discussion was about the marketing war that started after this drug was introduced in India, and how doctors were involved in it. I asked the following five questions.

Question 1

More than 15 brands of these drugs are available in India: How do you choose a brand for prescription? The options are:

- I will prescribe by generic name.

- I will ask my patient if he/she has any preference.

- I will choose a brand at random or by rotation.

- I prescribe a brand by my considered choice.

- Any other?

Most gastroenterologists in the audience who responded conveyed that ‘they choose one or two reputable brands, which will provide maximum benefit to the patient’.

Now we needed to clarify ‘reputable brands’ and ‘benefits to patients’.

My follow-up question was, ‘Which of the following pharmaceutical firms marketing these drugs were not reputable: Abbott, Alembic, Biocon, Cipla, Hetero, Dr Reddy's, Emcure, Gilead, Mylan, Natco, Ranbaxy/Sun, Wockhardt, Zydus Cadila/ Heptiza?'

I got no replies. Reputation means the medicines manufactured by these companies have been genuine and effective. Obviously, all were reputable.

The most explicit answer was given by one of my panellists. ' I will prescribe by brand name and I confine my brands to just a couple for convenience. Mylan because I feel the originator has to get credit, and Dr Reddy's because they were among the first to organize an informative continuing medical education (CME) programme with international faculty and followed it up with patient support. For patients who are receiving the drugs from another source such as employees of public sector undertakings, I prescribe by generic name.'

For the USA, all these 15-odd brands being marketed in India may be generics, but in India these drugs are not marketed as generics; they are available as competing brands.

I asked another follow-up question, ‘If you prescribe by the pharmacological name in your prescription, it will mean that the onus of selecting the brand is on your hospital pharmacy or the shopkeeper who sells it. Is this acceptable?'

I could hear loud voices from the audience, ‘No, it is not acceptable. Pharmacists are more likely to be influenced by profits/market forces.'

In effect, everyone accepted that market forces influenced the decision and no one wanted the decision to go out of their hands. Hence, I decided to ask the second question related to ‘maximum benefit to the patient’.

Question 2

‘Patients save maximum money if you prescribe by a particular “brand” and refer the patient to a medical representative (MR, this term is also being used for other representatives of PC's marketing department). As we all know, MRs are often seen waiting about outside all busy outpatient departments (OPDs).'

I gave pros and cons of this decision, ‘It will be beneficial to the patient as the MR would arrange to provide drugs cheaper from the stockist/distributor (30%-40% below the maximum retail price [MRP]) and will also arrange to subsidize investigations (tests for HC V RNA and genotype are expensive) as a promotional activity. Most MRs can also counsel patients to be regular with (buying) treatment. However, the flip side is that the patient may think that the doctor has a side deal with the MR! ' I asked the audience, ‘Would you like to do it?'

There was a loud chorus, ‘No, it is unethical! MRs have no business hanging about outside OPDs, or meeting with patients, leave alone reminding them or counselling them.'

My follow-up question was: ‘You all said that you want to give maximum benefit to the patient? It is only through the MR that you can provide a subsidy to the patient. If you tell the MRs that PC A is providing package X for these drugs, four other companies will be willing to either match or provide a more attractive package.'

There was no answer. One panellist said, ‘Using these services may indicate complicity. I do not use them at all.'

' Which means you are not giving any benefit to your patients, which is available for asking,' I commented.

Someone from the audience shouted, ‘We all do it, but no one is willing to accept here!' I thought that was a truthful statement.

Question 3

‘Next scenario: One MR approaches you and offers to conduct a free survey in an area/village of your choosing on your behalf. You all know there are a lot of hotspots of HCV in villages of northern India. That MR will provide all the logistic support for the survey, which can later be published in your name ! Patients found positive will be sent to you for treatment or you can prescribe them on your once-a-month visit to the village. Your consultation fee will be taken care of and patients will only have to pay for medicines they consume, that too, 25% below the maximum retail price. It is a win–win situation for everyone: you will get a paper in your name and consultation fee, the patient will get early diagnosis and economical treatment and the MR will get to show increase in sales. Is it ethical for doctors to accept such an offer?'

I could hear loud murmurs from the crowd. A few in the audience had earlier presented results of such surveys. They obviously kept quiet. Those who stood up to answer strongly condemned the proposal. ‘It is unethical! MRs have no business carrying out surveys.'

My panellists said, ‘There are no free lunches. The PC as well as you are doing it for some profit. That again indicates a doctor-pharma nexus.'

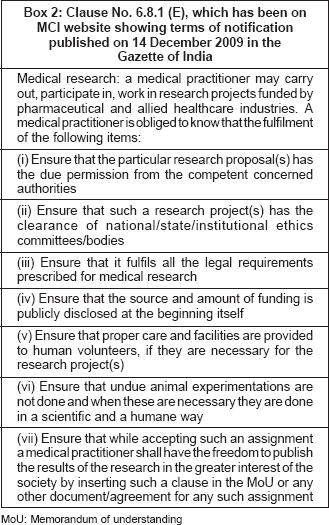

Then I showed the audience the Medical Council of India (Professional Conduct, Etiquette and Ethics) regulations, 2002 [Box 2]. Unfortunately, scrutiny for these stipulations was never done while accepting such research for presentation or publication in Indian institutions.

Question 4

‘PC “A” wants a meeting of top hepatologists to advise them about the launch of a new hepatology product. You have been chosen as an esteemed adviser. The PC wants you to attend a 2hour meeting in a hotel in Mumbai. Your travel stay will be taken care of. You will be paid an honorarium for the service rendered. It will be transparent as per law, and a contract will be signed as per ethics approved by the Medical Council of India (MCI). Should one accept?'

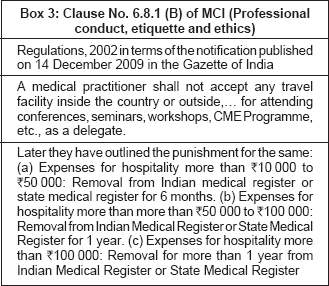

This question had a mixed response. People expressed conflicting opinions. Some found it unethical (obviously they had never been asked) and others said it was acceptable (they possibly had been asked). One panellist gave a clear reply, ' This is a tricky one. I feel, in principle, it is ok to accept. However, I make it a point to accept such an offer only from a company whose products I prescribe anyway. If it is a company that I do not usually prescribe or a product that I do not anyway prescribe I would not accept the offer. For instance, I never prescribe SAMe or glutathione in my practice. I would not accept if the meeting was related to those drugs. The MCI guidelines also permit that’ [Box 3].

This was a peculiar situation. Ethics permitted you to be affiliated to a PC, accept payment from them and be obliged to them. The caveats given were difficult to assess. How it will affect one's behaviour was of no consequence.[8]

Question 5

‘PC “X” wants you to attend Digestive Diseases Week 2017 (DDW-17) as their adviser (they will foot the bill). In return, you have to take part in three CMEs to give talks, with the aim to distribute knowledge gained at DDW-17 to other physicians in the area of your practice. There will be no condition on what you speak. '

This is where organizers wanted me to stop early. However, a chorus from the audience permitted me to go on. Everyone was shouting, ‘Tell us who is PC “X”? I want to go.' It seemed everyone suddenly wanted to attend DDW-17. Some commented, ' Why should we give talks, I will never submit to such blackmail. ' This was obviously another way for PCs to win over doctors’ loyalty to their products.

I projected another slide that showed MCI guidance [Box 3], outlining penalties for accepting travel facilities and hospitality from PCs.

There was silence. We all knew in our hearts that conferences are organized by funds from PCs. Approximately, 90%, if not all, of delegates and faculty attending these professional conferences (when they are not funded by the government/employer, which happened in <10% cases) were funded directly or indirectly by PCs. Reality was far from what was ideal.

The organizers at this point snatched the moment to flash a slide saying ‘your time is up’. I thanked everyone and closed the session. However, the same evening, I was accosted by several colleagues and PC representatives. My colleagues were happy that a different kind of topic was discussed. PC representatives had a mixed response. Some were unhappy because they had approached me with the proposals I had mentioned. I had not only accepted their proposals but also made them public. Some were happy and said that they had been manipulated by doctors into accepting similar proposals which came not from PCs but really originated from doctors. Since their own career advancement depended on the sales targets they could achieve, they had no option but to accept it if they were getting good business.

I asked them, ‘Forget that you are representing a PC. Imagine you are a gastroenterologist. How will you select a brand to prescribe?'

They all laughed. But one of them, a marketing vice-president of a PC answered, ‘You want my honest answer?' ‘Yes, of course.'

He answered without a smile, ‘I will prescribe just as most doctors do. I will prescribe a brand that fetches me (as doctor) the maximum benefit! '

I raised my eyebrows, ‘And what about the MCI Code of Conduct?'

His response, ' Sir, you also know. MCI does not know what is happening in their own basement. Who has time to find out what is happening in a corner of the country?'

A senior hepatologist, who was standing next to me and listening to this conversation, addressed me with his characteristic smile and said, ‘We doctors are hypocrites. We are walking on shit, but keep trying hard not to slip!' I was left wondering, if this was true!

Acknowledgements

I am grateful for inputs by Panel Members Drs A.V. Siva Prasad, Anil Arora, Aabha Nagral and Manav Wadhawan and many others who contributed to the discussion.

Financial support and sponsorship. Nil Conflicts of interest. None

| 1. | 57th Annual Conference of Indian Society of Gastroenterology; 15-18 December 2016 at Aerocity, New Delhi. Available at www.isgcon-16.com (accessed on 17 Dec 2016). [Google Scholar] |

| 2. | Jogalekar A. (Don't) Mind the gap: Manufacturing costs and drug prices. Available at https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/the-curious-wavefunction/dont-mind-the-gap-manufacutring-costs-and-drug-prices (accessed on 17 Dec 2016). [Google Scholar] |

| 3. | Pianin E. Costly hepatitis ‘C’ drug makers face new fire. The Financial Times. 4 December 2014. Available at www.thefiscaltimes.com/2014/12/04/Costl;y-Hepatitis-C-Drug-Makers-Face-New-Fire (accessed on 16 Apr 2014). [Google Scholar] |

| 4. | Chhatwal J, Kanwal F, Roberts MS, Dunn MA. Cost-effectiveness and budget impact of hepatitis C virus treatment with sofosbuvir and ledipasvir in the United States. Ann Intern Med 2015;162:397-406. [Google Scholar] |

| 5. | Watson J. Hepatitis C: Weighing the price of a cure. Medscape 21 May 2015 (accessed on 17 Dec 2016). [Google Scholar] |

| 6. | Hepatitis C drug delayed by NHS due to high cost. The Guardian. Available at www.theguardian.com/society/2015/jan/16/sofosbuvir-hepatitis-c-drug-nhs (accessed on 17 Dec 2016). [Google Scholar] |

| 7. | Australia's rejection of costly new treatment sofosbuvir a death sentence for hepatitis C sufferers. Available at www.abc.net.au/news/2014-10-23/rejection-of-costly-new-cure-a-death-sentence-for-hep-c-sufferer/5837484 (accessed on 17 Dec 2016). [Google Scholar] |

| 8. | Anand AC. The pharmaceutical industry: Our ‘silent’ partner in the practice of medicine. Natl Med J India 2000;13:319-21. [Google Scholar] |

Fulltext Views

1,826

PDF downloads

521