Translate this page into:

What are the options to implement an undergraduate medical exit examination in India?

2 Department of Medicine, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Ansari Nagar, New Delhi, 110029, India

Corresponding Author:

Piyush Ranjan

Department of Medicine, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Ansari Nagar, New Delhi, 110029

India

drpiyushdost@gmail.com

| How to cite this article: Sarkar S, Ranjan P. What are the options to implement an undergraduate medical exit examination in India?. Natl Med J India 2021;34:46-48 |

Abstract

Medical education and assessment processes in India are expected to undergo a paradigm shift with the introduction of the National Medical Commission Act, 2019. The Government of India intends to introduce a national exit test (NEXT) which is supposed to act as a single examination for graduation from medical school, granting licence to practice modern medicine, and allocating postgraduate residencies. As the nature, scope and stakes of these are different, various options regarding the content and conduct of the examination require careful consideration. We explore the options for implementation of this examination on a national scale. These options include theoretical (multiple assessment methods) with clinical examinations, multiple-choice question (MCQ)-based examination with separate clinical examination, only an MCQ-based examination, and multistep examination including screening followed by mixed assessment methods and clinical evaluation. We discuss the possible strengths and challenges of different options of implementing NEXT, and the caveats of the options.Introduction

The National Medical Commission Act, 2019[1] aims to develop a system that improves access to quality and affordable medical education, and ensure the availability of competent medical professionals across India. One of the key provisions of the Act is the conduct of a ‘common final-year undergraduate medical examination’, the National Exit Test (hitherto referred to as NEXT) for granting a licence to practice modern medicine in India and for entry to postgraduate courses in broad specialties. This is a departure from previous practice, wherein the licence to practice was granted after passing the university examination and entry into postgraduate courses was decided through competitive entrance examinations. The reasons for coalescing these into a single examination are presumably to bring uniformity in minimum competencies for practising medicine and to reduce the protracted pressure on trainees to prepare for competitive examinations to get into specialties of their choice for postgraduate training. As these changes venture into uncharted territories, the Act gives ample scope and time to devise regulations and implement mechanisms for NEXT.

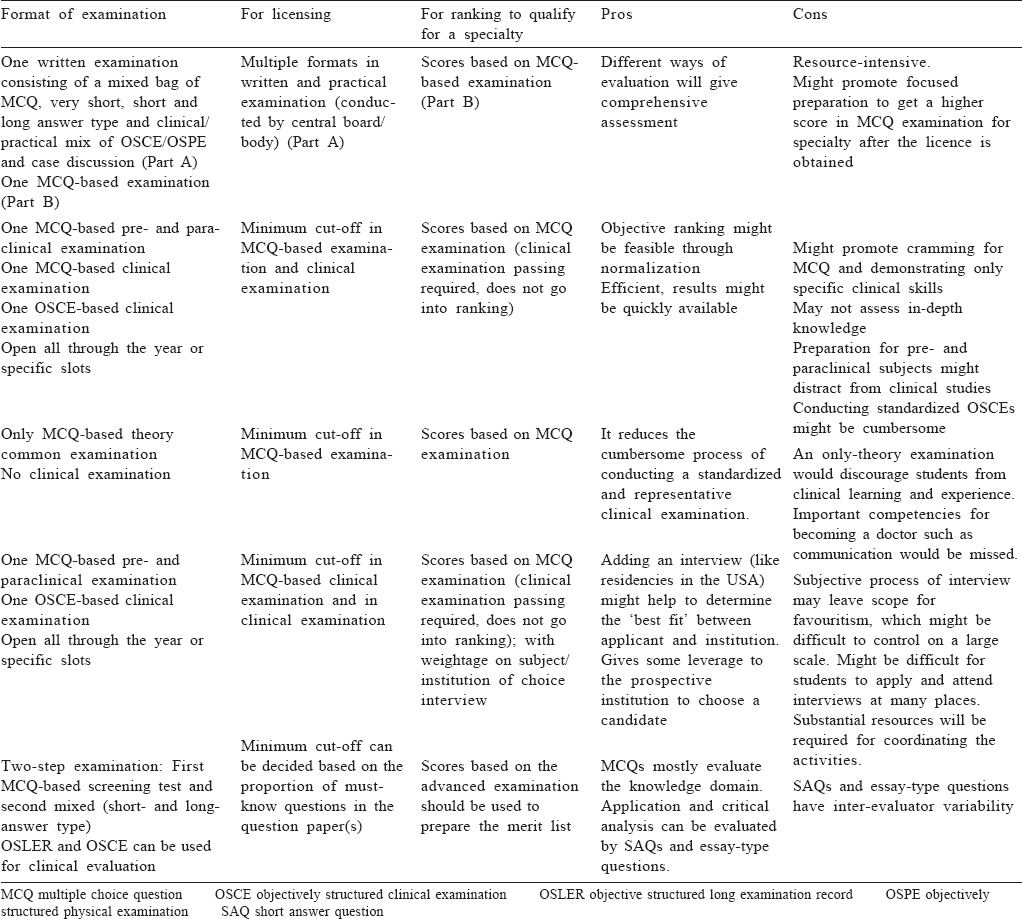

The premise of having NEXT brings challenges of deciding the processes and mechanisms of the examination, which are fair (stands external scrutiny), feasible (which could be administered among graduates from all over India), functional (is able to help decide who passes and who gets a particular specialty), focused (on relevant competencies of a doctor) and flexible (adapts with changes in medical education with time). Examples for such common licentiate examinations are available across the globe, including the United States Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) and the National Medical Practitioners Qualifying Examination in Japan. To conduct such an examination for more than 70 000 students graduating annually from more than 450 medical colleges in India would be a mammoth task. This would need careful deliberation and reasonable preparation. Some considerations for such an examination are given in [Box 1]. We offer some possible scenarios on the conduct of the examination and the pros and cons of each approach [Table - 1]. The following scenarios are not exhaustive and are meant to further discussion on the issue. As a caveat, we would like to mention that there might not be a universally acceptable ‘best’ method[2] and there may be trade-offs on certain parameters.

One possible way could be along the lines of USMLE that has two multiple-choice question (MCQ) examinations: one focusing on pre- and paraclinical subjects, and the other on clinical knowledge. The USMLE also has a clinical examination in the format of objectively structured clinical examination (OSCE). Acceptable performance in clinical examinations (OSCEs) and knowledge evaluation (MCQs) would allow for a licence to practice. The determination of cut-off for licensing may be made through either percentile scores, expert consensus, or based on results of concurrent administration of these tests on the average practising clinicians. The normalized scores and percentiles in these examinations may determine the matching of a candidate to a specialty.

A variation of such a system would be to focus on only the final-year clinical subjects for the theory examination, as it integrates knowledge from pre- and paraclinical subjects. Although such a framework of assessment would make scoring easier and transparent, there might be a disproportionate focus on ‘cracking’ such a high-stakes examination. In addition, some individuals who get a licence might be tempted to appear multiple times till they get a suitable rank which allows them a place of choice. Restricting the attempt at this examination to one might put immense pressure on examinees and might force them to purposefully fail when they believe that the examination is not going well.

Another possible variation could be organizing NEXT in two parts, namely Part A, for licensing examination which would include subjective questions in theory paper and OSCE and case discussions in clinical examination. Part B, an MCQ-based examination could be organized for the entrance examination for postgraduate courses. Part A can be organized by either a dedicated central board or health university created for this purpose. The nature of questions of the two examinations can be different, due to differences in the scope of evaluation, nature of stakes and feasibility.

Yet another possible option could be to conduct NEXT in two steps. The first step would be a screening test (MCQ-based), and the second one would be the advanced level examination that will have mixed-type questions (MCQs, short-answer questions and modified essay-type questions). This pattern of evaluation may have better validity although the process would be resource-intensive. A similar pattern of examination is being used successfully in two prestigious competitive examinations, i.e. Union Public Service Commission (UPSC) examination and Indian Institutes of Technology Joint Entrance Examinations (IIT-JEE).

There are certain developments that we should guard against, or at least take cognizance of as we move forward. One of them is students’ focus on getting a specialty of choice versus learning clinical skills during their clinical training. Students’ study based on what is assessed. If they are assessed on pieces of information through MCQs, then their training and attention might be skewed based on what would potentially be asked in MCQs.[3],[4] Hence, clinical case-based scenarios assessing the understanding of clinical practice in the subject would be better than knowledge-based questions. However, to give their best in high-stakes examinations, students might be forced to unduly focus on the examinations, skip clinical classes and attend focused coaching to perform better, relegating the process of gathering essential skills and clinical knowledge to a later date. Therefore, a clinically relevant and practice-based examination will be more contextual for students for their subsequent clinical practice.[5] Another issue would be to generate a ranking order for students for the specialization of choice, and then placing them in the institutions listed in their choices.[6],[7] The test should be able to discriminate a large number of students based on performance on the questions and the methods used. The third issue would be the conduct and coordination of such a task. This should preferably be carried out by inscrutable and specialized agencies which have practical experience of conducting such examinations. Such examining bodies should not be swayed by concerns of feasibility and practical constraints, but strive to make trustworthy and competent doctors.

In conclusion, we present certain options that may be considered while rolling out NEXT in India. The intent of NEXT is laudable, but devising a scaled-up functional system would probably require some forethought in planning, and afterthought in dealing with exigencies as they emerge. The implementation would mean that some thought might be needed in the way the curriculum is designed and re-designed, and the role universities and medical colleges would play in educational experiences and certification. We hope that the medical education and assessment system evolves in India based on the unique needs and challenges, and NEXT provides a robust benchmark which other medical education and licensing systems are able to learn from.

Conflicts of interest. None declared

| 1. | The National Medical Commission Bill, 2019. PRSIndia; 2019. Available at http:/ /prsindia.org/billtrack/national-medical-commission-bill-2019 (accessed on 8 Jul 2019). [Google Scholar] |

| 2. | Epstein RM. Assessment in medical education. N Engl J Med 2007;356:387–96. [Google Scholar] |

| 3. | Vyas R, Supe A. Multiple choice questions: A literature review on the optimal number of options. Natl Med J India 2008;21:130–3. [Google Scholar] |

| 4. | Hift RJ. Should essays and other “open-ended”-type questions retain a place in written summative assessment in clinical medicine? BMC Med Educ 2014;14:249. [Google Scholar] |

| 5. | Sharma A, Schauer DP, Kelleher M, Kinnear B, Sall D, Warm E. USMLE step 2 CK: Best predictor of multimodal performance in an internal medicine residency. J Grad Med Educ 2019;11:412–19. [Google Scholar] |

| 6. | Kenny S, McInnes M, Singh V. Associations between residency selection strategies and doctor performance: A meta-analysis. Med Educ 2013;47:790–800. [Google Scholar] |

| 7. | Go PH, Klaassen Z, Chamberlain RS. Residency selection: Do the perceptions of US programme directors and applicants match? Med Educ 2012;46:491–500. [Google Scholar] |

Fulltext Views

1,592

PDF downloads

936